Somewhere in the clouds over the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, or wherever his soul resides, Joseph P. Kennedy must be smiling. Having labored to immortalize himself through the greater glory of his nine children—or at least his four sons, whose careers he orchestrated as surrogates of his own—he has now succeeded. A man whose greatest talent lay in making money, and whose goal in life was to preserve as much as possible—“an Irish Sammy Glick…driven by nothing beyond personal gratification, which included his immediate family as an extension of himself,” in Herbert Parmet’s unkind but not inaccurate phrase—he was neither a particularly admirable nor even a significant figure in American life. His claim to our attention comes not from his public positions, but from his private ones. It is as sire that Joseph P. Kennedy is renowned. His is a case of the virtues of the sons being visited upon the father.

Having grasped after but never fully attained the heights of power he felt were his due, he was determined to achieve them through his progeny. His instrument was to be his eldest son, but when Joseph, Jr., was killed in the war, the mantle then passed to the second son. “I got Jack into politics, I was the one,” the elder Kennedy said to an interviewer. “I told him Joe was dead and that therefore it was his responsibility to run for Congress. He didn’t want it. He felt he didn’t have the ability and he still feels that way. But I told him he had to.”

Jack’s responsibility? To whom? Certainly not to himself, for the father had earlier planned on the illness-prone second son becoming a university president. No, the responsibility was to the father’s unfulfilled ambitions. I told him he had to. And John F. Kennedy—sickly, diffident, insecure, overshadowed by the brother who bore his father’s name and his father’s dreams (“I’m not bright like my brother Joe,” Jack once confessed to his college adviser)—did as he was told.

Well, the rest, as they say, is history. But not so well known a story as we might think. Herbert Parmet’s Jack, despite a title that trivializes a serious and scrupulously researched work, for the first time puts the Kennedy story into perspective. Parmet provides a great deal of fascinating information, even for those, like myself, who thought they could never bear to read another word about the Kennedys: Although far too long (this volume takes Jack only to the 1960 election), it moves along smartly and is filled with fascinating detail. For the first time someone has told the Kennedy story straight. Now psychohistorians can go to work on this superman of our own creation, John F. Kennedy.

He was, of course, no superman at all. In fact, some of the time he could barely get out of bed, suffering as he did from scarlet fever, backaches, a wartime wound, and later Addison’s disease. He was our sickliest president. “At least one-half of the days that he spent on this earth were days of intense physical pain,” his brother Robert once wrote. He never expected to live beyond the age of forty-five, and it suggests the degree of his grit and his thespian abilities that he was able to convey an impression of youthful vigor.

John F. Kennedy grew up in the shadow of his older brother, and spent a great deal of energy trying to emerge from the benevolent domination of his father. The elder Kennedy was not an easy man to shake. He lived for and through his children, impressing upon them that all his sacrifices were for their sake alone. How ungrateful they would be if they failed to achieve the ambitions he set for them. He loved them so much. How could they let him down? Joseph P. Kennedy was, for the sons in whom he inspired such admiration and guilt, the ultimate Jewish mother.

One of the virtues of Parmet’s study of the son is that it puts the father in his proper place. He tells us what we need to know about the elder Kennedy. That is, though he dominated the lives of his sons, he played a minor part in the life of the nation. In the obsession with the Kennedys—a price we pay for lacking an official royal family—writers tend to forget the distinction between the family and the nation, or to confuse the latter with the former.

Now that the Kennedy lode has been mined pretty thoroughly, there is the temptation to dig even further back into marginal property. Jack, at least, was president, and a straightforward biography of the sort Parmet has done, without the gee-whizzes or the axe-grinding of earlier works on the subject, is a welcome relief. But Joseph P. Kennedy, paterfamilias, is another matter. He had, to be sure, made his way to the top through a combination of guile and brutality, but this in itself did not mark him off from others of his class. And he did not, after all, start at the bottom. His father, a wholesale liquor distributor with ambitions, sent him to Harvard. There he polished his technique sufficiently to marry the daughter of the mayor of Boston and to gain control of a bank in which his father had a partial interest by the time he was twenty-five. He got into the movie business early, churning out B movies and gaining control of a theater chain, whose assets he milked for several million dollars.

Advertisement

At that point Joseph Kennedy, having left Boston for the wider horizons of New York, turned his attention to politics. Franklin Roosevelt enters here. Most people know the bare outlines of Kennedy’s involvement with the New Deal: that FDR made him the first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“Set a thief to catch a thief,” Roosevelt explained of this curious choice of stock market manipulator to police Wall Street), shelved him briefly at the Maritime Commission, and then in an act of perversity in the spring of 1938 sent him to London as ambassador. A hustler to police the stock exchange, an Irishman to the Court of St. James. “It’s the greatest joke in the world,” FDR said. But the joke was on him.

There is an interesting vignette in the relationship of this pair of con men: each supremely sure of himself, each trying to manipulate the other. But it was an absurdly unequal relationship, for Kennedy was little more than a gnat that flitted over the surface of FDR’s consciousness. The problem with Michael Beschloss’s book—a problem evident in the title, Kennedy and Roosevelt—is that it assumes an equation between the two men that never existed. The author has done his research diligently and has labored hard to persuade us that this is one of those fateful historical encounters, perhaps like that of Louis XIV and Richelieu, or Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House. “In their uneasy alliance, Joseph Kennedy and Franklin Roosevelt were finally more effective men—both in league and in confrontation—than they would have been on their own,” he tells us. Nonsense. Kennedy was not Harry Hopkins, or even Cordell Hull. He was merely an office-seeker who was bought off with relatively unimportant jobs and discarded when he ceased to be useful.

One would like to praise the young and promising Mr. Beschloss. This book was based on his undergraduate dissertation, and he has turned it into an informative, if sometimes plodding, historical memoir. But the strain of a faulty premise is his undoing. He fails not for lack of trying, but because his book has a basic structural flaw. He could have written a biography of Kennedy, emphasizing the conflict that he touches upon only peripherally between Kennedy’s convictions and his ambitions. Or he could have examined the failures of FDR’s European policy in the late 1930s, using Kennedy’s tenure at Grosvenor Square as the focal point. But to write a parallel biography of two men whose lives touched only peripherally and whose relationship approximated that of a feudal monarch and a court attendant is to miss the point. The book wheezes with the strain of its own inflated premises.

The trouble with Joseph P. Kennedy was not that he was greedy, and unprincipled, but that he was essentially a trivial man. He never wanted anything, except money and social approval, enough to inconvenience himself seriously for it. He did not even want power, although he said he did, because he never had any idea of what he would do with it. He mainly wanted to get back at all those Boston Brahmins who had snubbed him, who drove him to flee snobbish Cohasset for Hyannis Port, to abandon Brookline for a huge house in Bronxville, a retreat in Palm Beach, and a French Renaissance chateau outside Washington. This is why he was forever sniffing around FDR, waiting to be thrown a bone. His support for Roosevelt, as Parmet points out with a directness in refreshing contrast to Beschloss’s circumspection, “was based on the fact that he felt he had found a winner and would profit from being in the winner’s circle.”

Joseph Kennedy entered FDR’s life as a conniver and a flatterer, and went out the same way. He gave money to the 1932 campaign, and expected to be rewarded with a suitable post: in this case secretary of the treasury. No sooner was Roosevelt inaugurated than Kennedy sent him an effusive telegram of congratulations, recounting his visit to a convent where the “nuns were praying for you,” and the Mother Superior had declared that his inaugural had seemed “like another resurrection.” FDR took the comparison to Jesus in stride. Breezily expressing his thanks for the “awfully nice telegram,” he urged Joe and Rose to “stop off and see us” if they ever happened to be passing through Washington.

Advertisement

After a few months of FDR’s artful evasions, Kennedy took the direct approach. First he tried to buy off FDR’s economic adviser, Raymond Moley, by offering to “supplement” his government salary so that he could live in Washington in proper style. When Moley declined, an impatient Kennedy threatened to sue the Democratic National Committee to get his campaign loan back. With no appointment in sight, he set sail for England with James Roosevelt. Knowing that prohibition was on the way out, he dangled the president’s son before British distillers and came back with a number of lucrative liquor franchises. Finally in the summer of 1934 FDR found a job for “old Joe” and told Kennedy he could be chairman of the newly formed SEC.

He carried out his job with exemplary skill and efficiency, even winning the applause of his critics. But he soon grew bored regulating the stock market, and set his sights higher. With the treasury still off limits—FDR had no intention of letting a conservative make economic policy—Kennedy decided that a proper place for a man of his qualities would be the Court of St. James. The choice is instructive. A man seeking political power would not settle on an ambassadorship. Embassies assuage a man’s vanity, not his lust for power. FDR understood this, which is why he never took Kennedy seriously as an adversary. Kennedy was useful to him as a link to the business community and to the Irish-American establishment, including such luminaries as Kennedy’s friend Father Charles Coughlin, the “radio priest.”

Kennedy arrived in London shortly after the Anschluss. “I am still unable to see that the Central European developments affect our country or my job…,” he reported. He saw nothing to deplore in Mussolini’s conquest of Ethiopia, protested vigorously when he heard that FDR was contemplating lifting the embargo on arms to the Spanish Republic, and applauded the Munich settlement. He dined regularly with the so-called “Cliveden set,” and thought Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement the quintessence of enlightened diplomacy. He told Hitler’s ambassador in London that he thought American Jews were giving FDR a biased impression of Nazi Germany.

He was an appeaser and anti-Semitic, but more from greed than from any deep intellectual conviction. American involvement in a European war, he believed, would be bad for his investments. His prime concern was to protect his profits. “Isn’t it wonderful?” he said to the incredulous Czech minister in London after hearing the news of the Munich sell-out. “Now I can get to Palm Beach after all.”

Even though he feared that FDR’s policies were leading the country toward a war he dreaded, he could never quite bring himself to break with the president. This reluctance was not from loyalty, but from fear of being locked out of the inner circle. In October 1940, with the country torn by the debate over the lend-lease bill, Kennedy returned to Washington for consultations, darkly hinting that he would denounce FDR as a warmonger. No sooner did he step into the Oval Office, however, than his resolve collapsed. FDR worked his charm and a glassy-eyed Kennedy fell into line. A few days later he went on the radio to support the third term.

FDR got what he wanted. Now he could rid himself of an encumbrance. With the election safely over, he summoned Kennedy to Hyde Park. There he demanded an explanation of the press interview his ambassador had just given declaring that “democracy is all finished in England.” It was bad enough for Kennedy to tell people at London dinner parties that they ought to give up and sign a deal with Hitler. But to say it to the American press was to undermine FDR’s camouflaged efforts to lead a hesitant nation toward all-out support of Britain. Ten minutes after he entered the president’s study, Kennedy was sent packing. “I never want to see that son of a bitch again as long as I live,” FDR said. “Take his resignation and get him out of here.” Eleanor pat him on the afternoon train to New York.

Yet even then Kennedy never openly stood up to Roosevelt. He resigned in silence, hoping that FDR would give him another job. He waited in vain. Finally in 1943 he turned to his old friend J. Edgar Hoover and volunteered as a “special service contact” for the FBI.

From Palm Beach Kennedy piled up more millions of dollars through real estate deals, such as his acquisition of the Merchandise Mart, and entertained fleeting fantasies of occupying the Oval Office himself. But that dream was to be lived through his second son, one of whose greatest challenges was to surmount the reputation and influence of his father. Jack Kennedy never broke with his father, never openly defied him. Yet he did resist the smothering embrace. Interestingly, his undergraduate thesis, a short little volume spruced up by one of his father’s hangers-on, Arthur Krock, and entitled Why England Slept, was mildly critical of the Chamberlain appeasement policy that Joe found so enlightened. One redeeming virtue of John F. Kennedy was that of all the sons he was the least like his father.

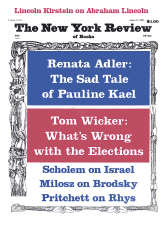

This Issue

August 14, 1980