Virginia Woolf could be icily curt about the phenomenon of “Bloomsbury” emerging during her lifetime. On March 19, 1932, she told an American academic, Harmon H. Goldstone, that “the name ‘Bloomsbury Group’ is merely a journalistic phrase which has no meaning that I am aware of.” To the same academic’s persistent queries, she replied on August 16, 1932: “The Bloomsbury Period. I do not want to impose my own views, but I feel that Bloomsbury is a word that stands for very little. The Bloomsbury group is largely a creation of the journalists. To dwell upon Bloomsbury as an influence is liable to lead to judgments that, as far as I know have no basis in fact.” Harmon H. Goldstone must have been very obtuse indeed if he could not detect the tone of the final dismissive comment: “I am sorry not to be more helpful; but as I think I have already said, I am sure you will write better if you are fettered as little as possible by the views of the author.”

Volume V of her Letters, covering the period 1932-1935, is the saddest of any of the collections to date, yet it captures what was rare and splendid about a remarkable group of friends. By 1932 Virginia Woolf was fifty, and in the three ensuing years she experienced the deaths of many of those dearest to her, the recognition of the disintegration of love, the atrophy of her creative powers, and an overwhelming sense that madness was enveloping Europe.

The year 1932 opened with the death of Lytton Strachey. To Ottoline Morrell she wrote on February 8: “We must always hoard the memory of him up together—that will be something real—otherwise, running about London and finding everything going on, I am aghast at the futility of life—Lytton gone, and nobody minding. But with you, who loved him, some reality comes back. So you must let me come sometimes.” To Dora Carrington, on the very day of Strachey’s death, she wrote:

Darling Carrington,

We are all thanking you for what you gave Lytton. Please Carrington, think of this, and let us bless you for it.

This is our great comfort now—the happiness you gave him—and he told me so.

Virginia

After two suicide attempts herself, Virginia sensed that Carrington’s death was inevitable. Her anguished knowledge breaks through in a letter written a week before Carrington shot herself:

Oh but Carrington we have to live and be ourselves—and I feel it is more for you to live than for any one; because he loved you so, and loved your oddities and the way you have of being yourself. I cant explain it; but it seems to me that as long as you are there, something we loved in Lytton, something of the best part of his life still goes on. But goodness knows, blind as I am, I know all day long, whatever I’m doing, what you’re suffering. And no one can help you.

In April the Woolfs accompanied Roger Fry and his sister to Greece. Leonard Woolf has recorded how Virginia would succumb completely to holidays and this one was particularly important to her because the presence of the Frys reassured her that the associations she had treasured were still vital. The talk was almost incessant, the Frys delighting her with their inexhaustible storehouse of arcane facts, and the scenery was “marvellous, miraculous, stupendous.” But, back in England, death resumed its relentless pursuit—first Lowes Dickinson—“the most charming of men—the most spiritual”—in August. To Roger Fry, Virginia wrote:

My dear Roger,

We want just to send one line—there was nobody like Goldie and I know what his death must mean to you. How I hate my friends dying!

Please live to be a thousand. You cant think what you mean to us all.

Love from us both

Your

Virginia

Then on September 9, 1934, Roger Fry died of a heart attack. “He was the most heavenly of men,” she told her friend and admirer, the elderly composer Ethel Smyth, “—so I know you’ll understand my dumb mood,—so rich so infinitely gifted—and oh how we’ve talked and talked—for 20 years now.” As she has Rose exclaim in The Years, talk is “the only way we have of knowing each other.” Francis Birrell’s death followed in 1935. To Ethel Smyth she cried, “But what, my dear Ethel, do you think it all means? What would you have said to a friend—25 years I’ve known him—dying at 45, full of love of life,—just beginning to live? And we both knew he was dying: and what was there to say about it? Nothing. I feel like a dead blue sea after all these deaths—cant feel any more.” Like Maggie in The Years, she raises her arms “as if to ward off some implacable destiny; then let them fall.” Yet it was Fry’s death more than any other over which she continued to torture herself. Walking through Regent’s Park after a rainfall in June 1935 she was flooded with a sense of ecstasy by the luminous haze, but the mood was momentary for “I am in the cavernous recesses…because Roger is dead (I never minded any death of a friend half so much: its like coming into a room and expecting all the violins and trumpets and hearing a mouse squeak).”

Advertisement

She also watched with horror the disintegration of T. S. Eliot’s marriage. Her uneasy relationship with Ethel Smyth erupted from time to time into bursts of anger. As she recognized from the outset, their minds were integrally different. On one occasion she analyzed their difficulties as arising from the fact that they had met late in life so that they could not possibly share the same friends; and in trying to avoid friction by controlling characteristics that irritated each other, “aren’t we diminishing our own peculiar light?” During these years she was particularly nervous and jealous that Vita Sackville-West, the woman for whom she seems to have had the strongest sexual feelings, was drawing away from her. She begged Vita to tell her that she loved her best after her husband and sons. In May 1933 she was horrified to learn that Vita’s mother had told her grandson Ben Nicolson about his parents’ sexual proclivities. In February 1935, she recalls nostalgically to Vita: “My mind is filled with dreams of romantic meetings. D’you remember once sitting at Kew in a purple storm?” In March, in making arrangements to motor over to Sissinghurst for tea, she ends on a plaintive note:

And do you love me?

No.

It was on this particular occasion, according to Quentin Bell, that she realized that their passionate relationship was irrevocably over.

These years were filled with blinding headaches, fainting spells, and frequent rest periods ordered by her doctor to calm her intermittent pulse, although she reassured everyone that her heart was perfectly sound. There were no money worries because, as Leonard Woolf’s tables show, even during the Depression, the sales of her books continued to mount. They could afford pictures and an expensive car, and she was constantly pressing gifts on Vanessa. She realized that she had become famous but she refused to serve on committees, to sit for her portrait for the National Portrait Gallery, to accept all honors, even the Clark Lectureship although she knew how much it would have pleased her father if she had agreed to deliver it.

She had always worked slowly, but creatively this was the most difficult period in her life. Flush she regarded simply as a tour de force written to amuse Lytton who was no longer there to be amused. After Roger Fry’s death she was reluctantly persuaded to write his biography, the least successful of all her books because she felt so inhibited by what she could not say. “This long weary dreary book,” she described it to Vanessa. Her increasing lack of confidence is reflected in her attitude to Proust. In May 1934 she tells Ethel Smyth that his work is “so magnificent that I cant write myself within its arc.” After seeing Eliot’s highly successful Murder in the Cathedral at Canterbury in June 1935, she confides wistfully to Vanessa that “success is very good for people. I wish I were successful.”

She seemed to know from the outset that The Years (originally called The Pargiters) would not be successful. She worked at it intermittently and in frenetic bursts of energy, but talked about ultimately having to consign it to the flames. Its slow progress she blamed on the interruptions of her friends and the interminable manuscripts to be read by the Hogarth Press. By November 1934 she could tell her American publisher Donald Brace that it was in effect finished, although she admitted her perplexity about it and her fear that much of it would have to be rewritten. Apprehensively she gave it to Leonard to read. When he had finished, he probably lied to her for the first time in his life: “I think it’s extraordinarily good.” In the last paragraph she had written, “death is the enemy,” and the whole book had been written in the shadow of death. The novel was a failure because she could not write about a world—her world—that was disappearing forever. In each section of the book, which spans the period 1880 to the present day, someone dies. The pattern of movement, the joyous revelations, the attempt to encapsulate life itself had become a lifeless formula.

The countryside around Rodmell was being ruined by cement works and cheap bungalows. The Night of the Long Knives—June 30, 1934—in which Hitler ordered the killing of some of the leading Nazis horrified her. To Ethel Smyth she wrote: “For the first time almost in my life I am honestly, without exaggeration, appalled by the Germans. Cant get over it. How can you or anyone explain last week end! Their faces! Hitler! Think of that hung before us as the ideal of human life! Sometimes I feel that we are all pent up in the stalls at a bull fight—I go out in the Strand and read the placards, Buses passing. Nobody caring.” To Quentin Bell the following year she envisaged a Bloomsbury dominated by “a Platz with a statue of the Leader.” By October 1934, when Mussolini launched his attack on Abyssinia, she complained of not being able to sleep for thinking of politics.

Advertisement

But it must not be thought that these letters contain nothing but loss, desolation, and death. When over fifty she set out with determination to learn to speak French properly. Her description of Rebecca West to Quentin Bell is a flash of the old Virginia: “Rebecca is the oddest woman; like an arboreal animal grasping a tree, and showing all her teeth, as if another animal were about to seize her young. This may be the result of having a son born out of wedlock.” To Ethel Smyth on August 27, 1934, she exclaimed: “How fierce and perennial the love of country is!” Yet she continued to love London as much as ever. In October, when they had moved back to the city, she was telling the same correspondent, “I like Hyde Park fading into night, only the flowers burning in a few pale facades. I love overhearing scraps of talk by the Serpentine in the dusk; and thinking of my own youth, and wondering how far we live in other peoples and then buying half a pound of tea, and so on and so on.”

She loved solitude—in August 1933 she had “three entire days alone—three pure and rounded pearls”—only to be interrupted by the unwelcome appearance of Kingsley Martin. In October, as she was packing to return to London, she confessed to Ottoline Morrell: “I rather dread London. I feel less and less able to control my life and I go on saying yet it is the only life I shall ever have. Why waste it? However, it wont be a waste if you’ll come one evening or let me come in the gloaming. I like the October evenings in London. It has been almost beyond belief beautiful here—I walk and walk by the river on the downs in a dream, like a bee, or a red admiral, quivering on brambles, on haystacks; and shut out the cement works and the villas. Even they melted in the yellow light have their glory.”

Her playfulness bubbles out in response to a gift of shortbread from Elizabeth Bowen:

What a dangerous friend you are! One says casually I like shortbread—and behold shortbread arrives. Now had I said I like young elephants, would the same thing have happened? I suspect so. The only way to neutralise the poison is to cancel it with something you dont want, here’s a book therefore. But be warned—I often make tea caddies in magenta plush—that will be your fate on the next occasion. I embroider them with forget-me-nots in gold.

She had her dislikes of course—Kingsley Martin, D. H. Lawrence (“a cheap little bounder”), and Cyril Connolly and his first wife (“a less appetising pair I have never seen out of the Zoo, and the apes are considerably preferable to Cyril”). She was interested in young emerging talent and intelligence—Stephen Spender, Isaiah Berlin, Christopher Isherwood, even Noel Coward who called her “darling” and gave her his glass to drink out of. “These are dramatic manners,” she told Quentin. “I find them rather congenial.”

Her mind remained open, too, to the possibilities of a new type of novel. In a letter to George Rylands in 1934 she compares the Victorian novelist with novelists of her generation who “became aware of something that can’t be said by the character himself; and also lost the sense of an audience.” After discussing the transition from one type of novel to another, she speculates: “Perhaps we must now put our toes to the ground again and get back to the spoken word, only from a different angle; to regain richness, and surprise.”

This brings us to the interesting and highly intelligent novel of Leonard Woolf, The Wise Virgins, written just after his marriage to Virginia in 1912. It is the story of what might have happened to Leonard if he had not escaped his stultifying Jewish background or gone to Cambridge and become an Apostle, and, above all, what his fate could have been if Virginia had not married him.

The novel was published in 1914 (and not republished because his mother was offended by his portrait of her); but Leonard did not give it to Virginia to read until the following year, perhaps because, as Ian Parsons’s introduction suggests, he was apprehensive of her reaction following her third attack of mental illness.

Leonard had recently returned from his years as an administrator in Ceylon. With this experience behind him, he sees people’s gregariousness—in their propensity to feel comfortable among their own kind—as a self-protective device imposed by civilization. This, then, is a novel about social distinctions, a roman à clef, and an account of the experience of loving someone very different from oneself.

The class distinctions and social divisions Woolf writes about seem to be as real today as they were when Leonard Woolf wrote this book. First, there are the very conventional Garlands living in suburban Richstead (which might have been Chiswick or Putney, where the Woolf family actually lived). Woolf’s description of the Garlands’ garden with its carefully cultivated flowers is a brilliant device to emphasize their eminent respectability among their peers. The Garlands become acquainted with the Davis family, and their friendly determination to ignore the Jewishness of the Davises is a mark of commendable Christianity. Their only really difficult adjustment is to Harry Davis who is given to making curt, enigmatic remarks. (Leonard Woolf at this age, Quentin Bell tells us, was “a strange wild man of powerful intellect.” He probably, too, recognized in himself something of Leonard Bast. Howards End, after all, had been published only four years before.)

Harry is an art student and at class he meets the elusive Camilla Lawrence, who possesses “almost a sixth sense of sensitiveness.” Camilla takes him to her Hyde Park home where he meets Mr. Lawrence, whose “immobility partook of the permanent and his lassitude of the sempiternal.” Here, too, he meets her practical-minded sister Katharine and their intellectual friends. Woolf is splendid at conveying the differences in conversation among the separate social groups. One can very well imagine from this novel the gauche young Leonard’s first encounter with the element of play in Bloomsbury talk. Mr. Lawrence’s pronouncements take on the intonations and implications of which Leslie Stephen delivered himself.

“The place you live in must be comfortable—that’s the first thing. People must leave you alone; there must be proper arrangements for moving your mere body from one place to another place when you are foolish enough to wish to move; the food must be eatable; people must speak to you in a decent language. I expect, my dear Milla, London is the only place which is properly arranged in those ways. Anywhere in Germany, of course, is impossible—they are such intolerable people. In France, there’s the food, it always upsets the digestion; and Italy’s the same, only it affects one rather differently. All foreign languages are intolerable.”

Fun, yes, but such insularity, in its way, was just as typical of Bloomsbury as it was of Richstead. Virginia Woolf never read Freud, never mastered a foreign language, and invented a crass America as she followed by letter Vita and Sir Harold Nicolson’s lecture tour in 1933, or an exotic land of pampas grass and butterflies for the Argentina of her “crush,” Victoria O’Campo.

But it is Camilla who opens Harry’s eyes to the unbearable narrowness of the virgins of his world. Gwen Garland is fascinated by Harry and by the new possibilities in his life to which Camilla has now introduced him. Harry, however, has already fallen in love with Camilla; the ecstatic description of a walk they take on the downs is doubtless based on one which Virginia and Leonard actually shared. Camilla turns down Harry’s proposal, and in despair he joins the communal Davis-Garland family holiday at Eastbourne. The newly awakened Gwen throws herself into Harry’s arms and he has no alternative but to seduce her—and to be doomed to a life of narrowness and conventionality. What one senses in this novel is Leonard Woolf’s relief that Virginia chose to marry her “penniless Jew.”

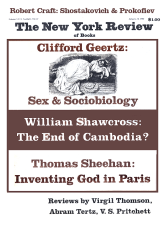

This Issue

January 24, 1980