In response to:

Being Strong: Edmund Wilson's Letters from the October 27, 1977 issue

To the Editors:

Harry Levin, in the course of reviewing a recently published volume of Edmund Wilson’s (Letters on Literature and Politics: 1912-1972), writes that in Here at the New Yorker “Brendan Gill has insinuated that Wilson sought financial advantage for himself in the arrangements he finally made [for the publication of The Crack-Up] with the more receptive firm of New Directions” [NYR, October 27]. It is important for your readers to know that I made no such insinuation. On the contrary, the point of what Levin later calls my “malicious anecdote” is precisely that in the case of The Crack-Up Wilson behaved with exemplary generosity. Levin mentions Wilson’s “admitted toughness with publishers,” which is putting it mildly and kindly. In my book, I tell of the reputation Wilson had among young writers in the 1930s and 1940s for being a sort of Robin Hood, constantly seeking to outwit (not without certain lapses of scruple) his and our natural enemies, the publishers. I then write:

When Fitzgerald died, in 1940, Wilson as his close friend and literary executor put together a volume of Fitzgerald’s uncollected work, including his essay on his breakdown, selections from his notebooks, letters to him from Gertrude Stein, Edith Wharton, and John Dos Passos, and poems to him by John Peale Bishop and Wilson. Edmund brought the manuscript to Scribner’s, Fitzgerald’s regular publishers, whose editors immediately turned it down. They had already let much of Fitzgerald’s work go out of print—at one point, all of Fitzgerald’s work is said to have been out of print—and they saw no reason to believe that the public would be interested in these mere sweepings from a dead author’s desk. Wilson carried the manuscipt from publisher to publisher, in vain; at last, he brought it to James Laughlin, of New Directions…

Laughlin consented to publish the Fitzgerald volume, and for once Wilson was outwitted: the Fitzgerald estate was to be paid the conventional royalty, but Wilson was paid a fee, amounting to only a few hundred dollars. The outwitting was unintentional and without malice; neither Laughlin nor Wilson expected the book to sell well, a dozen other publishers having declared that it wouldn’t sell at all.

In short, Wilson accepted a small fee and saw to it that the royalties went to the Fitzgerald estate. To make sure that nobody reading of this arrangement in the seventies would suppose that Wilson was disappointed at not receiving royalties, I went on to say “In those days, moreover, it was the invariable custom to pay the editor of a book, or the author of an introduction to a book, a flat fee.” The fee was small, for the reasons stated; Wilson was outwitted in working so hard for so little only because, to the general surprise, the book did well. There is no implication whatever in what I wrote that Wilson sought “financial advantage for himself,” especially at the expense of his dead friend. Mr. Levin is a far less accurate explicateur de textes than I had up to now supposed.

Brendan Gill

New York, New York

Harry Levin replies:

I don’t quite see how my text need be modified by Mr. Gill’s explication. Interested readers may judge for themselves by looking at the full context of his original remarks. I am glad he has again brought up this question of Wilson’s relations with the literary marketplace, since I have just learned that his estate received nothing out of the large sum paid for the film rights to The Last Tycoon, despite the crucial part he played in putting the story together.

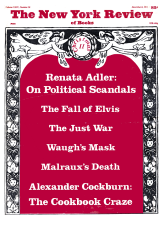

This Issue

December 8, 1977