This year marks the centenary of the publication of Johannes Brahms’s First Symphony. An international colloquium, largely funded by American taxpayers, will be held at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, and twenty scholars from various countries will discuss Brahms’s life, work, and influence.

Fact or fiction? Someone may know. But at a time when “junketing” by our politicians is much in the news, and the new Ethics Code has refused to put serious restrictions on it, the present volume comes as a reminder that there are foundations as well as government agencies that deserve the order of the Golden Fleece. In his preface to the issue of Daedalus (Summer 1976) in which these papers first appeared, the chief editor and organizer, Stephen R. Graubard, acknowledged generous grants from four foundations, thanks to which the colloquium was held in Rome, “the only possible city…. Any other would have been wrong.” This volume, like the issue of Daedalus, contains no record of the “animated discussions” which, according to Professor Myron Gilmore’s introduction, took place at the sessions. As far as the reader is concerned, the papers might as well have been mailed to an editorial board at Harvard. Would that have been “wrong”?

In any case, there are anniversaries and anniversaries. Almost any occasion can be commemorated when it suits someone to do so. In the Roman Empire that was Gibbon’s subject, the vow, the foundation, and the completion of a public building could provide matter for separate anniversary commemoration.1 The centenary of a great man’s birth or death is a legitimate occasion. Not all important figures are as fortunate as Gibbon in finding affluent sponsorship for their posthumous fame: I do not know of any conference commemorating the bicentenary of the birth (also in 1776) of Barthold Georg Niebuhr, whose important contribution to the development of modern historical scholarship could do with major reevaluation. The centenary commemoration of Gibbon’s death, in 1894, was (as Myron Gilmore reminds us) a memorable event for scholarship in various ways. But what is actually commemorated here is the appearance, in February 1776, of the first volume of the History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Perhaps we may expect major commemorative efforts for the bicentenary of the appearance of volumes 2 and 3 (March 1781); of the completion of the work, just before midnight on June 27, 1787—as Gibbon takes care to specify, in a formal companion-piece to the description of the supposed conception of the work on the Capitol; and of the publication of the last three volumes in 1788. By then we shall be well on the way toward the bicentenary of his death.

I

This volume reproduces the twenty papers that appeared in Daedalus, with one substitution (Myron Gilmore’s introduction for Stephen Graubard’s preface), with the order changed (we are not told why), and with an inadequate index added. A few typographical errors have been corrected, but most—even serious ones—remain. Reuben Brower died before the conference and is represented by what the editors rightly call a “delightful travel sketch”—musings on Gibbon in modern Puerto Rico. Of the eighteen substantive papers, three appear in translation: Professors Starobinski and Furet wrote in French, Professor Giarrizzo in Italian.2 Regrettably, that fact is nowhere mentioned. In fairness to both author and readers, any translation surely ought to be marked as such, even if the actual translator does not want to acknowledge personal responsibility. The poor standard of linguistic competence nowadays makes that imperative. The translations from the French are arbitrary but intelligible. If the translator does not know the English for the names Juste-Lipse or Lucain, that hardly matters. If he does not know the meaning of “altération” (as it happens, a key word in Starobinski’s paper), that is misleading but not fatal. “From the age in which we live, what can we expect?”—as the translator renders Voltaire.

We must, however, expect better than incompetence, which is what we get in the translation from the Italian. It is to be hoped that Giarrizzo; who in this English dress is often incomprehensible, will some day publish the original text of his interesting paper on Gibbon’s Lehrjahre.3 Errors range from the merely slapdash (“seventeenth century” for “settecento“) to the absurd (“he can hand over his estates…just as a shepherd [sic] can give away his sheep”). Sometimes (e.g., p. 244, on the decline of the city of Rome) whole paragraphs are reduced to meanings not intended or to nonsense.

The selection of contributors was clearly aimed at producing a mixture. There are few dedicated “Gibbonians” (one misses Hugh Trevor-Roper and Sir Ronald Syme). The editors’ idea of having Gibbon illuminated by specialists in various fields on which he touches was commendable. Having chosen their men (only one woman), they—again very properly, in principle—do not seem to have indicated required topics. This would have worked well, had the conference not been so grossly overfunded. The result is crowding of some obvious fields, with overlap even where it is least needed. The first two papers treat (basically) the same subject: Gibbon’s personality and the image he chose for himself. Neither has anything interesting to say, for anyone who has read any elementary book on Gibbon (e.g., Professor David P. Jordan’s own: his is the first paper). Martine W. Brownley’s contribution is characterized by such gems of penetration as: “Gibbon’s whole life was composed of constant adjustments of his expectations.” And her dabbling in psychohistory in treating what she predictably calls “affairs of the heart”—especially Gibbon’s relationship with Suzanne Curchod, the remarkable woman whom, obeying as a son, he did not marry after promising to—invites comparison with Georges Bonnard’s superbly sensitive discussion in his appendix to his edition of Gibbon’s Lausanne diary,4 a work apparently not known to her.

Advertisement

It is always illuminating to see how, in an obscure corner of scholarship, old fancies linger on: Ms. Brownley’s is not the only example of how the work of the specialist tends to be ignored by the non-expert trying to acquire a serviceable smattering. Gibbon’s vision as he “sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol” (where there were no ruins) while the barefooted friars were singing vespers is one of the most widely known “facts” about him. It is frequently mentioned in this volume. Jordan, of course, is fully aware of the history of this passage: first written twenty-five years after the event, with pretended reference to a diary entry, it was twice rewritten, with changes in substance as well as style. But it cannot all be invention: “There is no evidence to suggest that Gibbon invented the chanting friars who interrupted his melancholic reverie on the Capitol” (that interruption is actually in none of Gibbon’s versions); at most he was “bending or stretching the truth.”

Gilmore and Giarrizzo cautiously suspend judgment on the famous episode, and perhaps that is a wise thing to do. But Robert Shackleton, in a disappointing study of French influences on Gibbon, contrasting unfavorably with (e.g.) Starobinski’s, accepts the truth of “that memorable day” without a word of caution. And François Furet, whose paper (“Civilization and Barbarism in Gibbon’s History”) shows him to be one of the most perceptive of these scholars, but also one of the least informed about Gibbon, except for a few obvious highlights from the History—Furet regards the great moment as giving “a meaning to his life amounting almost to a religious conversion.” It is a pity that Gibbon, after that conversion, tried his hand at various other projects (see Giarrizzo) before settling on the History, years later.

The facts, after Georges Bonnard’s exemplary work, are known—or should be.5 Gibbon’s diary does not cover his stay in Rome. That of his companion William Guise (unfortunately not published in full, as far as I know) does. They visited the Capitol six times in the eight days between October 6 and 13, 1764. On the fifteenth—the “memorable day”—“being wet weather this Morning,” they visited an English painter: no mention of a visit to the Capitol. As Bonnard comments, we can save Gibbon’s basic credibility (even though the details kept changing in retrospect) by imagining that the rain stopped and Gibbon then went to the Capitol by himself, while Guise refused to accompany him—which he does not seem to have done previously. It takes faith (in Voltaire’s sense of believing what reason does not believe) to make these assumptions, which are (strictly) irrefutable. Bonnard’s urbanity in presenting the hypothesis may have deceived superficial readers into believing that he kept an open mind. However, several of the contributors to this volume have simply not read Bonnard.

II

A reviewer obviously cannot even mention all of the papers. Among those I most enjoyed, without much temptation to be persuaded, Peter Brown’s mannered virtuosity is, as always, enthralling: his Gibbon, the metaphysician of “reality” and “folly,” emerges as a sharply etched, if not a very Gibbonian, figure; and Arnaldo Momigliano, no less entrancing despite forbidding catalogues of names, presents Gibbon as an éminence grise in the development of Italian thought, unperceived even by the most distinguished Italian scholars. Others would deserve praise, or at least a mention: let it be stated that silence does not mean contempt.

Those papers most fully justifying the editors’ principles of selection are the papers by scholars who, without becoming involved in Gibbonian mythology, comment on Gibbon’s place in their own special fields. The names of Steven Runciman on Byzantium, of Bernard Lewis on Muhammad, of Owen Chadwick on Gibbon and the Church historians, promise high quality, and do not disappoint. These scholars adopt a basically similar approach, showing us in detail (what surely few readers will know, even if specialists) the sources of information that Gibbon actually had available and how his attitudes, shaped by the Enlightenment, affected his use of those sources. Islam became what Lewis describes as the myth that [Western] Europe has always needed “for purposes of comparison and castigation”—he compares the United States in the nineteenth century and the Soviet Union earlier in the twentieth (one might now add China): it seems to have been Gibbon, the civilized gentleman horrified by that other popular version of such a myth, the “noble savage,” who popularized the interpretation of Islam in those terms. Both here and in the case of Byzantium, on which Gibbon was obviously no less prejudiced than Runciman is, Gibbon’s interpretation long remained the only one known to the educated public.

Advertisement

Chadwick’s paper (one of the most impressive in the volume) shows Gibbon trying to overcome his own prejudices as he aims at impartiality between Catholic and Protestant historiography—but never stopping to consider the standards he himself was applying; and using predecessors like Baronius and Tillemont, with due acknowledgment, to the full while asserting his superiority by a mocking detachment. Chadwick usefully reminds us that in 1776 “the fires of Seville were close” and the burning of witches was to go on for some time yet. The time was not yet ripe (we might say) for the myth that the historian must understand without judging. We are barely emerging from it again.

III

Gibbon, of course, regarded himself as a “philosophical historian”: he often makes his own comments in the persona of “the philosopher.” As Starobinski points out, the relationship between philosophy and erudition, a much discussed subject in contemporary France, is one of the main themes of his first work, the Essai sur l’étude de la littérature (1758-1759). Even then, history is to him a combination of both: “Si les philosophes ne sont pas toujours historiens, il seroit du-moins à souhaiter que les historiens fussent philosophes.” At the time, only Tacitus seems to him to embody this ideal. He always liked to be compared to Tacitus, and he returned to his model: G.W. Bowersock convincingly argues that, when Gibbon, near the end of his life, regretted that he had not started the History at the death of Augustus or the death of Nero, he was thinking of the starting-points of Tacitus’s main works.

Several of the contributors concentrate on the philosophical aspect. Frank Manuel, while acknowledging the influence of Voltaire’s esprit on Gibbon (who would have hated this judgment), stresses the influence of Hume above all (“There is not a virtue Hume extolled that Gibbon would have failed to embrace”); and others write on similar lines. J.G.A. Pocock sets Gibbon in the wider context, which Pocock has done so much to elucidate, of the history of “civic humanism” and of the interaction of that ideal of the commonwealth governed and defended by its (propertied) citizens (one might call it the “militia republic”) with the incompatible one of civilization coming about through material progress. Pocock is very clear on the theoretical importance of the ideal of the militia republic to Gibbon: on this view, the decline of Rome was due to the fact that its citizens, through over-refinement, ceased to govern and to defend themselves. He notes the conflict of this view with Gibbon’s profound convictions about the primacy of refined civilization.

Perhaps the conflict is not strictly philosophical. Scholars writing about philosophy (not only in this volume) have tended to take Gibbon the Philosopher too seriously. Manuel gets very close to facing this alarming possibility. Furet, the most complete outsider to “Gibbonian scholarship,” says it straight out: “Gibbon was, in fact, indifferent to the political philosophy that so excited many of his contemporaries. He wrote, as did his masters in antiquity…, moral history…. The emperors of the second century were his exempla.” Despite his genuine and profound erudition, Gibbon was a philosophe far more than a philosopher, though he hankered after being a philosopher of history.

“L’histoire est pour un esprit philosophique…[la science] des causes et des effets.” So he had said in the Essai (ch. XLVIII). The History was certainly meant to exemplify it. The General Observations at the end of his original project (his volume 3) show that he was then claiming to have provided a philosophical answer to the problem of the decline and fall of Rome. As several of the contributors stress, he had done nothing of the sort. The scattered remarks relevant to the point that are made in the course of the work hardly correspond to the summary he now gives.

The General Observations perform several functions. First, they try to reassert his title to the status of philosophic historian. Next, they aim at allaying the neurotic fears of those who saw a parallel between Rome and eighteenth-century Europe, as Manuel and (from a different point of view) Starobinski demonstrate in fascinating detail. (Our own age is full of similar fears and attempts to allay them, and we have no right to laugh at Gibbon.) Finally, they play down the importance of the Church in the process of decline and fall. This contains an element of personal insurance: Gibbon had no martyr’s vocation, and he had seen, with some genuine surprise, the offense given by his first volume. It is interesting that in his last chapter (71, at the end of volume 6) he returns to conciliation, acquitting the Church of responsibility for the decay of the Roman monuments.6 Yet it is fair to say that, whatever other motives may have entered into these concluding passages, he is not seriously misstating his position: the Church, in many of its manifestations, arouses the fighting spirit and the esprit of this English philosophe, but it is not his villain.

The primary cause of the decline and fall was the disintegration of imperial defense. This, in concrete terms, he regards as his problem, most clearly in the first part of the work. But the “explanation” is by no means as “simple and obvious” as he claims in his summary. Not that he was aware of the full complexity of the phenomena he was dealing with: he was far too close to his ancient models for that. It is only at the end of his whole work, in chapter 71, that some appreciation of this can be seen to have crept in; even then, it is not developed. But within his narrow frame of reference, his “explanation” is both unintelligible and contrary to the facts he has collected. His search for causes, as Chadwick points out, is—following a long tradition—a search for villains. There is a gallery of them, and Gibbon changes his mind, as he goes along, about their relative responsibility. While searching for his villains—Septimius Severus, Caracalla, finally Constantine—he tries, uneasily and unsuccessfully, to connect their actions with successive stages in the disintegration of the militia republic, which he feels committed to regarding as the state of absolute virtue; or rather, since it had died much earlier, in the disintegration of its surviving ghost.

That he was indifferent to political philosophy is an overstatement; he was fascinated by it and fancied himself at it. We may compare his attitude to theology. In the one case the fascination was one of admiration, in the other of repulsion. His ineptitude at theology, though, is sufficiently shown by the convincing disproof of transubstantiation (as he thought it thirty-five years later) that he discovered at Lausanne.7 His attachment to philosophy, too, was abstract and literary. The various scholars discussing his philosophical background deserve thanks for painting the environment that he absorbed. But his genuine commitment (and again Frank Manuel sees it clearly) was to the social structure of his age.

This purely intellectual adherence to a philosophy remote from his deeper feelings may be compared to his purely literary display of “sensibility,” proper to an author and a gentleman of his time: his horror, in 1764, at “the magnificence of the palaces cemented by the blood of nations” (this, incongruously, in Turin—Giarrizzo takes it seriously); his announcement in the Essai that “l’histoire des empires est celle de la misère des hommes“; most characteristically, combining his chosen philosophy with his chosen sensibility, his treatment (Miscellaneous Works 4, pp. 394 ff.) of the triumphal pageant in the Roman Republic. The citizen watching it could identify with the general he had elected: “to receive its full impression, it was enough to be a man and a Roman.” However,

if a sentiment of compassion overcame his stern prejudices, and he melted at the sight of a fallen monarch and his innocent children, still unconscious of their misfortune, his tenderness must have been rewarded with that delightful pleasure with which nature repays such tears.

Laurence Sterne would have enjoyed it.

IV

It is not surprising that Gibbon thought the disintegration of Roman defense his main problem. At (to us) a superficial level, it was. Moreover, he had taken from his ancient models the view that “wars, and the administration of public affairs, are the principal subjects of history” (ch. 9). So much so that it never occurred to him to put that interest in the arts and in social and economic history and antiquities, which he displayed in his journals, to use in his History. This was not due to any profound reflections of a philosophical nature, as Francis Haskell here tries to argue in the case of art, and others have in the case of the other disciplines. Such topics were simply irrelevant—beneath the dignity of proper history. It has been so fashionable to regard Gibbon as a philosophic historian of the Enlightenment that the simple truth clear to Furet has usually been missed, as indeed much of this volume goes to show: Gibbon was essentially an ancient, not a modern, historian. His pronouncement on the limitations of history is an ancient attitude. His descriptions of Oriental and barbarian nations are in the best tradition of the excursuses in Sallust or Tacitus (not to mention Herodotus), and the evidence of those writers is freely mixed with that of recent travelers, without any attempt at critical discrimination: again, the interest is purely literary.

As for the sensibility he displays at proper times, it is conspicuously absent from the hundreds of battles, sieges, and massacres—rhetorically adorned after the manner of Livy, who, like the Captain of the Hampshire grenadiers, had never seen real war—that fill his pages in a bloody but unreal pageant. When, after a battle against the Visigoths, the “vulgar” among the dead are left unburied, his response is a characteristic display of wit (not included, we note, by John Clive in the anthology of Gibbon’s wit that he contributes to this volume): “Their flesh was greedily devoured by the birds of prey, who in that age enjoyed very frequent and delicious feasts.” We are reminded that he felt “more deeply scandalised at the single execution of Servetus than at the hecatombs which have blazed in the Auto da Fés of Spain and Portugal” (History, ch. 54). It is not too surprising to discover that he let his stepmother (of whom he was about as fond as he was of anyone) live in poverty, while using money that was rightfully hers in order to maintain his proper station in London.

It should be even less surprising, therefore, to see him putting his golden age some centuries after the period of that militia republic to which he proclaimed an orthodox attachment. His real spiritual home—not philosophically defended, but deeply felt—was a state in which a benevolent prince or oligarchy protected and defended a majority that did not really matter much. “While the Aristocracy of Bern protects the happiness, it is superfluous to enquire whether it be founded in the rights, of man”—so he wrote in 1791 (Memoirs, p. 185). When his deep-rooted preference emerges from the literary overlay, it turns out to be pre-Revolutionary France. At the end of chapter 19 of the History, he enthusiastically praises “the lively and graceful follies of a nation whose martial spirit has never been enervated by the indulgence of luxury,” together with “the perfection of that inestimable art which softens and refines the intercourse of social life.”

As we noted in the case of the “conversion” on the Capitol, Gibbon has had amazing success in imposing his image, not least on some of those who study him with the greatest devotion.

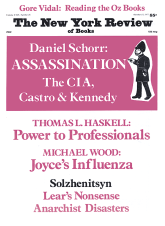

This Issue

October 13, 1977

-

1

See Michael Grant, Roman Anniversary Issues (Cambridge University Press, 1950): his introductory sketch, as he called it, discovered seventy-two commemorative issues.

↩ -

2

I should like to thank the editors, who courteously allowed me to see the original versions of these three papers, when difficulty with Giarrizzo’s led me to inquire.

↩ -

3

It is basically a summary of the relevant parts of his book Edward Gibbon e la Cultura Europea del Settecento (Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Storici, 1954).

↩ -

4

Le Journal de Gibbon à Lausanne (Université de Lausanne, Publications de la Faculté des Lettres 8, 1945) pp. 281-304.

↩ -

5

Edward Gibbon, Memoirs of My Life (ed. Georges A. Bonnard, Funk and Wagnalls, 1969). See p. 136, with notes on pp. 304 f.

↩ -

6

Pocock (p. 118) suggests that the famous phrase “the triumph of barbarism and religion” may refer “to the Arabs rather than the Germans, and to Islam rather than Christianity.” Although this is certainly an overstatement, the possibility that it refers to both (as Pocock almost implies in his preceding sentence) should be seriously considered, especially since the whole of chapter 71, in which the phrase occurs, is conciliatory and in part even friendly to Christianity and its representatives.

↩ -

7

Memoirs (ed. Bonnard), pp. 73 f.: “that the text of scripture which seems to inculcate the real presence is attested only by a single sense, our sight; while the real presence itself is disproved by three of our senses, the sight, the touch, and the taste. The various articles of the Romish creed disappeared like a dream .”

↩