When Arthur Waley’s translation of The Tale of Genji came out, volume by volume, in the late Twenties and early Thirties, the austere Sinologue and poet said that Lady Murasaki’s work was “unsurpassed by any long novel in the world.” If we murmured, “What about Don Quixote or War and Peace?” we were, all the same, enchanted by the classic of Heian Japan which was written in the tenth and eleventh centuries, and we talked about its “modern voice.” What we really meant was that the writing was astonishingly without affectation. Critics spoke of a Japanese Proust or Jane Austen, even of a less coarse Boccaccio. They pointed also to the seeming collusion of the doctrines of reincarnation or the superstition of demonic possession with the Freudian unconscious—and so on.

Arthur Waley admitted a remote echo of Proust, for there was a nostalgia for temps perdu in a small aristocratic civilization; but he was quick to point out that the long and rambling Tale was hardly a psychological novel in the Western sense. The Chinese had excelled in lyrical poetry, but despised fiction outside of legend and fairy tale; in Japan, Lady Murasaki’s contemporaries were given only to diarizing. What she had contrived was an original mingling of idealizing romance and chronicle, but a more apt analogy was with music: the effect of her classical and elegant mosaic suggested the immediate, crystalline quality of Mozart. Evocations of instrumental music and also of things like the music of insects occur on page after page: at one point Genji floods a garden with thousands of crickets. The more one thinks about this, one sees that Waley’s insight contains a truth: it is music that steps across the one thousand years that separate us from Lady Murasaki.

A translator like Waley would have European reasons for thinking her “modern”: Japanese art had played its part in the revolution that was occurring in European painting—see Van Gogh, and Picasso in the early 1900s—and English prose was ceasing to be Big Bow Wow. Both the sententious and the precious were yielding to the personal, the conversational, the unofficial, the unaffected, and the fantastic—one sees this in Forster and, above all, in Virginia Woolf, who had contrived an ironical mingling of the formal and natural. Such a change reflects the moment when a culture reaches a sunset in which private relationships are given supreme importance and when there is leisure for wit and perspective and an intense sensibility to the arts for their own sake.

I think this may go some way to explain why the post-1914 period in England produced brilliant translations like Waley’s, Beryl de Zoete’s Confessions of Zeno (which may have improved on the regional prose of Trieste, but captured the marked Viennese spirit of the original), Scott Moncrieff’s Proust, and Constance Garnett’s Chekhov and Turgenev. Their translations are gracefully late-Edwardian, and are, of course, metaphors; the translators felt an affinity of period, even though (as we are now told by critical scholars) they made serious mistakes or generalized and embroidered in such a way as to mislead. Since translators are bound to work in images, and not only sentence by sentence but paragraph by paragraph or page by page, generalizations tend to drift off course, and in some translators, the act of re-creation, though often inspired, is not self-effacing.

As both poet and scholar, Arthur Waley has often been suspected of reinventing with the willfulness of the poet. He was never in China or Japan: his enormous knowledge was that of the hermit of the British Museum. The generation that followed him are far from any belle époque and are dedicated technicians strictly bound to their texts. Professor Edward G. Seidensticker, an American scholar, belongs to this school. In his new translation of The Tale of Genji he tells us that he owes his admiration for the Tale to Waley’s often wonderful translation and says that Waley often genuinely improved on the original (with one or two exceptions) by drastic cutting when the book bored him. It has its longueurs. Seidensticker’s chief criticism of Waley is that he embroidered (as an admirer of Virginia Woolf might well do), that his language is far less laconic than the original Japanese, and that, more seriously, he did not catch the rhythm of Japanese prose. I would guess on rereading Waley that this may be true. Seidensticker’s translation, which gives the whole uncut, is still shorter than Waley’s! There was indeed a languor in his prose.

It is impossible to do more than point out a few of the 800 characters of the story which passes from episode to episode. The main dramas move among the large number of Genji’s love affairs, which are as various as those of Boccaccio. Princes and their trains move from the capital, where all is ambition and court gossip, to the country, where mysterious girls, usually of noble connection, have been hidden, protected only by corruptible or sentimental nuns or servants. There are soldiers but they do not fight. There is no violence. There are no crimes of passion. There are a few rather unpolished provincial governors—a despised caste. Lady Murasaki is as sensitive as Jane Austen is to rank and status, noting drily the pretentious who have come to nothing and the common who have risen. There are priests in their temples, soothsayers, exorcists who are called in to throw out demons, which are, as a rule, projections of jealous passion.

Advertisement

We see a society ruled by ceremonies and rituals and checked by taboos. Ill-luck, bad behavior, tragedy may be caused in one’s life by influences from a previous incarnation for which one cannot be held responsible. Lady Murasaki’s temperament is not religious: for her, religion is a matter of proper observances and manners. She has a taste for funerals properly conducted.

The sexual act is never described; the ecstasies of physical love are not even evoked conventionally as they are rather tiringly in The Arabian Nights. We see the lovers meet with a screen between them. They strike the string of the koto or exchange short poems to show their artistic skills. The touching of an embroidered sleeve causes alarm and desire; when the lover is admitted or breaks in, the servants retire and we have a full description of the lady’s clothes and her hair, but not her body. A coverlet is removed and the next thing we know is that night has passed and the lover is required to leave at dawn under cover of the perpetual mist, his sleeves washed by the dews. He hands the lady a sprig of blossom and sends her a two line poem with a conversational postscript. The book is almost entirely concerned with the interplay of feelings, joyful, sorrowing, and longing. All is rendered with classical restraint.

The magnificent and always engaging Genji dominates two thirds of the book and then with little explanation fades out of it. (Perhaps the manuscript has been lost.) He is incurably susceptible and unfaithful, but he makes amends to his conscience by behaving generously. Society deplores but forgives what are called “his ways.” He is the illegitimate and favorite son of the emperor—“a private treasure”—and he is scarcely more than a boy when he falls in love with his stepmother, the emperor’s second wife, who seems, in this incestuous society, to be an ideal. She has a child by him, but that is nothing. He is married off to Aoi, another woman years older than himself. They do not cohabit and she treats him like a schoolboy but in time he will love her deeply. Meanwhile he takes Lady Rokujo, his uncle’s wife, also many years older than himself, as his mistress.

Lady Rokujo’s violent jealousy of Aoi leads to one of the great dramatic scenes of the book, for if she is resigned to Genji’s casual love affairs, she finds his love of Aoi intolerable. The drama comes to a head at the Festival of Kamo. An enormous crowd of all classes comes to see the nobility ride by on horseback. There is a great traffic jam of fine carriages, among them Aoi’s. Lady Rokujo has gone incognito to the festival in a simple curtained carriage, to get one last glimpse of Genji, but her carriage and her attendants collide with Aoi’s. There is a brawl between the rival servants and Lady Rokujo is pushed into the background.

This affront is devastating. From now on the evil spirit of jealousy becomes a demonic entity. Aoi is pregnant, indeed about to give birth, and is found to be dying. The evil spirit has indeed entered her, and when the demented Genji speaks to her, she answers in the voice of Lady Rokujo. Powerless to control herself Lady Rokujo has projected her voice into the dying woman. It is a case of possession. Such scenes are not uncommon in romance, but this one is so well done that we believe it and feel the horror. A wild emotion has been transmitted and is recognizable as an emanation of the unconscious, for Lady Rokujo, who has not consciously willed this act, nevertheless feels remorse. It drains her of all desire to continue her powerful life at court: she goes to annul the magic that possessed her, in a nunnery. Had the scene been done in the high manner of romance it would be as unreal as a fairy tale; in fact the writing is restrained and therefore frightens us.

Advertisement

Genji’s “ways” continue rashly until he sins against protocol and is obliged to go into exile in the mountains. The whole court, even the offended emperor, is upset. There are many rough journeys over muddy tracks, in fog, snow, freezing winds, across flooded rivers. The amount of rain that pours down in the Tale must be about equal in volume to the floods of tears, whether of joy, grief, longing, or remorse, which so easily overcome the characters. The tears themselves are a kind of music, a note of the koto. In exile, Genji thinks of his new wife, Murasaki—she seems unlikely to have been the authoress—and of his other ladies. But Genji cannot really repent. He thinks of old lovers:

He went on thinking about whatever woman he encountered. A perverse concomitant was that the women he went on thinking about went on thinking about him.

A cuckoo calls—it is a messenger from the past or the world beyond death, not the mocking creature of Western culture.

It catches the scent of memory, and favors

The village where the orange blossoms fall.

Even the sinister Lady Rokujo is forgiven. She had been a woman of unique breeding and superior calligraphy. She replied in a long letter:

Laying down her brush as emotion overcame her and then beginning again, she finally sent off some four or five sheets of white Chinese paper. The gradations of ink were marvelous. He had been fond of her, and it had been wrong to make so much of that one incident. She had turned against him and presently left him. It all seemed such a waste.

The lady of the orange blossoms, an older mistress, writes:

Ferns of remembrance weigh our eaves ever more,

And heavily falls the dew upon our sleeve.

A Gosechi dancer, a wild girl, writes:

Now taut, now slack, like my un- ruly heart,

The tow rope is suddenly still at the sound of a koto.

Scolding will not improve me.

Genji spends his time among the fishermen of the wild Akashi coast and here, of course, temptation comes and he is sending messages to a girl hidden in one of the houses, a rustic, whose parents have “impossible hopes.” Her father is a monk, but soon stops his prayers when he sees Genji may raise her fortunes. Genji admires beyond the protecting screen:

Though he did not exactly force his way through, it is not to be imagined that he left matters as they were…. The autumn night, usually so long, was over in a trice.

No hope of a respectable marriage for her. All the same, Genji will install her in the capital later in the story and she will have her influence on his life. As usual, he is guilty about this secret. The girl had enhanced his love of his wife, to whom he confesses.

It was but the fisherman’s brush with the salty sea pine

Followed by a tide of tears of long- ing.

His wife replies gently but ironically, in words that have a bearing on the Calderón-like theme of the novel, i.e., that life is a dream:

That you should have deigned to tell me a dreamlike story which you could not keep to yourself calls to mind numbers of earlier instances.

And politely adds to her poem:

Naïve of me, perhaps; yet we did make our vows.

And now see the waves that wash the Mountain of Waiting.

She knows that Genji will not stand jealous scenes for one moment. Everyone knows it. His lasting defense of his adding new loves to old is that he never forgets, and he adds: “Sometimes I feel as if I might be dreaming and as if the dream were too much for me”: it is an attempt to define what life itself, with all its happiness and disasters, feels like.

Genji’s early love of mother figures perhaps necessarily accounts for the incestuous strain in him. His second wife (i.e., Murasaki) was taken into his mansion as a child and he has brought her up to think of him as her father. He flirts with the little girl; then, when she reaches puberty, he can’t control himself and gets into bed with her. It is a kind of rape. The girl is shocked and the sullen, silent aftermath is plainly and delicately shown; but ritual saves the situation. The required offerings of cakes are pushed through her bed curtains. Marriage follows and, in time, she adores him. She has after all married the ruler of the country; however, in years to come, she will find him playing the father game again. He has by this time installed his chief concubines in apartments in his mansion; each has her own superbly made garden. He is getting on—probably in his forties—and he likes dropping in for a chaste evening chat with some of the older ones. There is some discreet bitching among the women, disguised as two-edged gardening presents. One older lady sends the younger Murasaki an arrangement of autumn leaves with the words:

Permit the winds to bring a touch of autumn.

Murasaki’s garden is without flowers at this time. She replies with an arrangement of moss, stones, and a cleverly made artificial pine, with the words:

Fleeting, your leaves that scatter in the wind.

The pine at the cliffs is forever green with the spring.

The pine is a symbol of hopeless longing and Genji tells his wife she has been “unnecessarily tart.”

“What will the Goddess of Tatsuta think when she hears you belittling the best of autumn colors? Reply from strength, when you have the force of your spring blossoms to support you.”

The magnificent man is fortifying not only because he is benevolent by nature, but also astute.

After the deaths of Genji and his second wife, the novel is dominated by a new generation: Yugiri, Genji’s pompous son, and the young heroes and courtiers, Niou and Kaoru. These two are friends, who laugh and drink together, and also rivals. The important thing is the marked difference of their temperaments, and on this Lady Murasaki becomes searching. Niou is the handsome and dashing Don Juan or playboy who lacks Genji’s powers of reflection. Kaoru has a startling physical quality. In a story where the men are known by the scent they use, Kaoru has a body that needs none: its natural fragrance can intoxicate 200 yards away like the smell of some powerful flower. (It can of course betray where he has been!) If this perfume allures it does him no good: he is a neurotic, tormented, indecisive, and self-defeating Puritan who botches his feelings and escapes into the fuss of court administration at the crucial moment. Responsibility is his alibi and curse. The explanation of his insecure character is that he is a bastard incurably depressed because he does not know who his father is.

The rivalry between Niou and Kaoru begins with a long intrigue with two orphaned sisters who live in the Uji country, a solitude of howling winds and sad rivers. Elsewhere we hear the cheeping of the crickets, the songs of birds, but at Uji the music is the mournful, deafening, maddening music of waterfalls. Niou quickly conquers one of the sisters but only to make her his concubine and not his wife. Kaoru, who is in love with both girls, in his way, loses both. His trouble is that he is an intellectual whose real interest is religion. He will eventually take the vows of Buddhism.

The “novel” has by now almost ceased to be a work of worldly and poetic comedy and, in its last part, becomes a fast moving drama of intrigue and passion and dementia in which lying servants and old women play their part. (The analogy is extravagant, I know, but it is as if we had moved from, say, Jane Austen to an Oriental version of Wuthering Heights.) This final section, along with the opening one of the Tale, is by far the most gripping. It excited Arthur Waley! The drama arises from one more adventure of the rivals. Niou and Kaoru are this time in love with a simple, hidden girl of mysterious parentage called Ukifune. Kaoru loves her because she reminds him of the one he had lost earlier—memory, or being reminded of earlier loves, is a continuous musical theme—Niou is out for yet another rash seduction.

The girl is too young to know which of the two she loves and which is her friend; and in her misery decides to drown herself as girls always do, Lady Murasaki remarks, in the romances she has read. She attempts this and disappears, and is generally supposed to be dead. Indeed the servants arrange a false funeral in order to avoid scandal. They go out with a coffin containing her bedding and things, and burn them on the funeral pyre; the country people, who take death seriously, are suspicious and shocked by the hurry. They watch the smoke: it smells of bedding, not of a burning corpse. In fact, unknown to Niou and Kaoru and ourselves, Ukifune has been rescued and hidden once more in a temple. We see Niou shocked by grief for the first time in his life. (Lady Murasaki is remarkable in scenes of wild grief.) The extraordinary thing is her account of Ukifune’s loss of memory and speech after the “drowning”: it is done with astonishing realism and could be a clinical study.

Lady Murasaki is almost too inventive. She is, as I have said, properly class-conscious, quick to detect the vulgar, and is therefore capable of refreshing bits of farce. Pushing, common provincial governors or tomboys with bad accents are neatly hit off: “Pure, precise speech can give a certain distinction to rather ordinary remarks,” she notes like any lady in a Boston or London drawing room, circa 1910. Girls who talk torrentially become “incomprehensible and self-complacent.” Still eventually there is a chance that being in good society will cure them. On the other hand, don’t imagine that there is any deep difference between the aristocrat and the lowborn: the sorrows of life afflict all. Life is short, time swallows us up; old palaces fall into ruins, new ones take their place. Our life is a dream and, like the Tale itself, fades away.

As a translator Seidensticker matches Waley’s excellence in detail: it is a ding-dong rivalry. There are Anglo-American differences in talk and if Seidensticker’s manner is laconic this sometimes runs him into the heavily jaunty word. (Look back to that phrase “perverse concomitant” in my earlier quotation.) There are many amusing episodes in Seidensticker which are missing from Waley: on the other hand one grasps the whole more easily from Waley’s discursive pages even if he is artfully generalizing.

In his preface Waley has more to say by way of literary judgment in his stern, sensitive manner; Seidensticker’s preface is more informative about the peculiar history of the manuscripts and composition, and about Lady Murasaki herself. It is curious that literary work of this kind was solely an occupation for women in her time, and Seidensticker thinks that this may be because unlike the women of other Oriental cultures Japanese women were free of harem politics; also that they were less conventional than the men, who were tied to the bureaucracy and the endless ceremonies of the court. Lady Murasaki’s contemporaries were simply diarists; she was widowed early. Perhaps, in loneliness, she took the leap from memoir into the imagination, and, looking back, felt that “the good life was in the past”: this indeed is the meaning of Genji’s name.

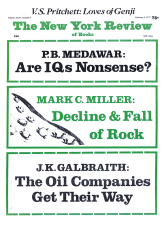

This Issue

February 3, 1977