The really good trials, for reasons that Aristotle could explain, have the power and appeal of folk drama. An evil deed has been committed off stage, now the chorus is assembled in a box to one side, the personified forces of destiny and the furies speak. If the trial is a criminal one, the satisfying ending seems to be when someone guilty is led off to prison, and if the trial is a politicial one, then the popular ending is freedom and vindication.

Some of the malice and confusion among the vast audience of the Patricia Hearst trial was probably owing to its being a modern play—qualified, ironic, and absurd—and it was hard to know whether it was about crime, as billed, or about politics, as it seemed. Either way, the trial did not satisfy, and the audience was restless throughout; petulant bombers let off bombs, reporters jostled and sneered, red-eyed Swarthmore dropouts lined up twenty-four hours in advance in hopes of seeing Her; assorted people, ignoring the fact that publicity is thought to harm defendants in trials, mounted an angry demonstration protesting that the white bourgeois press was paying too much attention to Patty and not enough to their favorite trial, of the San Quentin Six. Most people I talked to here in San Francisco said that they didn’t know much about trials, but they knew what they liked, and they hoped she’d really “get it.”

Indeed they probably could not have said why they felt that way. Seldom has the manifest content of the action (a “funky ten-thousand-dollar bank robbery,” one witness called it) seemed more unrelated to the latent content, the grounds on which she was actually tried and convicted—an outcome that seems to have precipitated a national mood of self-congratulation.

Among those who wanted conviction were, first, everybody who hates the Hearsts—this includes a lot of the press and a lot of Californians; the large number of people who hate the rich in general and are glad to see that they can be brought to trial the same as you and me; all those who hate radicals, and, related to them, those who mistrust anybody who takes the Fifth; and a group whose number we might have thought had diminished since the Sixties—those who mistrust the sexually “immoral,” people who smoke dope, spoiled brats who try to “get their own way,” and, in particular, undutiful children and rebellious women. How Patty got along with her parents and her fiancé Steve figured heavily in mail received against her by newspapers and government prosecutors. Finally, of course, we have all been taught to hate snitches. How cleverly the prosecution maneuvered the sympathies of these disparate elements into a symphony of public satisfaction.

Inside the courtroom the daily cast included the senior Hearsts, models of parental constancy, the fascinated sisters, F. Lee (called Flea in the San Francisco press) Bailey, a very smart man whose excellence as a lawyer was probably offset by local mistrust of smart imported lawyers, government prosecutor James Browning, a slow man who saw his main chance here, and the defendant, a five-foot-two-inch ninety-pound frightened young woman to whom all was happening just as her captors had promised it would. Under ordinary circumstances it is doubtful that any of these people would be in court at all, except perhaps in Judge Oliver Carter’s court.

This was kind of a bum rap. “Patty Hearst or ‘Joan Schmerdling’ would have been tried for this robbery,” Browning said, but in fact the government usually would not have rushed to prosecute probably the least culpable participant, one who had been kidnaped only seventy days before the crime and spent fifty-seven of those days locked in a closet. Even if we assume that she had by the time of the bank robbery joined her captors, that in itself is not uncommon, and precedent exists for the treatment of victims who accompany their captors in the commission of felonies. Duress is often assumed and such people are not prosecuted. There is considerable unseemliness in prosecuting the victim and not even charging the kidnapers. But here the government seems to have special reasons for the unusually harsh treatment of Patty Hearst.

First, it was probably sensitive, and rightly, to charges of bowing to Hearst money and influence. “Joan Schmerdling” would have had a better chance. Federal and local authorities must have seen, also, that beyond indulging their own fondness for prosecuting radicals, a Hearst conviction might set her up to turn state’s evidence in the penalty phase, something she was apparently not willing to do at the time of her capture, ostensibly because of fear, and possibly, of course, because of sympathy. It is also conceivable that the Establishment Hearsts rejected an initial option to have Patty plead guilty and hope for mercy (the sensible course), not because they had been given to understand that no mercy was forthcoming, but from a naïve confidence that their victimized child would triumphantly bob up. In the event, of course, she sank with the Fifth Amendment tied around her neck like a stone.

Advertisement

It is also possible that the government, by maintaining to the last that this was a serious revolutionary movement it had to protect us from, sought to mitigate the damage done to the prestige of the FBI and law enforcement in general by its ineptness and by the singular atrocity of police behavior at the SLA shootout in Los Angeles. The American treatment of a situation which would have been met, say in England, by bringing up a chemical toilet and a box of sandwiches for the long wait was a national disgrace abroad, however popular it may have been here. In its sudden and disproportionate violence, it seemed to reflect a peculiarly American taste in denouement.

In his summation, Browning reiterated the substance of the government contention that Hearst’s story of having been coerced into joining the SLA was “incredible.” “It’s too big a pill to swallow, ladies and gentlemen. It just does not wash.” To some it might seem more incredible that an abused and imprisoned victim could easily, without coercion, be taken in by the peculiarly incoherent ideology of the SLA, to say nothing of their cockroach-ridden life style. But the government usually seems to attribute to left-wing ideas an ineffable glamour which it supposes will make them irresistible to anyone but themselves.

By the defense the jury was asked to believe that the SLA treatment of Hearst was such that she felt forced to rob the bank to survive, and that thereafter—since there are seventeen months on the lam to account for—she went along with it in a state of demoralized acquiescence, convinced that the FBI was as likely as the SLA to kill her, and that her parents would not ever want to see her again; that her fear of law enforcement agencies was very reasonably increased by viewing the SLA shootout on TV and hearing Attorney General Saxbe denounce her as a common criminal; and that she was afraid of being charged in the bank robbery.

On the stand Hearst appeared forth-right but not forthcoming, an intelligent person who has for now exhausted her rather impressive range of adaptive responses. She could neither elaborate nor embroider, and sometimes simply could not answer to or account for her own actions. “I just don’t know what happened to me, Mr. Browning,” she had to say. A doctor who examined her at the time of her capture said that she is nevertheless dramatically improved since then, when she was literally stupefied and amnesiac. There is still much she cannot, or cannot yet, explain.

The jury could not believe her. They had seen that grinning, power-saluting picture, heard her say she was “pissed off” at being captured (in a conversation with a girlfriend, secretly recorded at the jail). The problem for Hearst was that the jury turned out to have no imagination. They could not imagine the kinds of life conditions people adapt to. They could not imagine that you might read the words of someone else into a tape recorder and not mean them, like poor Tokyo Rose, or could come to think you meant them. They could not imagine that they themselves, like most people, might clumsily assist, rather than resist, an assailant. They could not believe that there actually is such a thing as “coercive persuasion,” or that revolution can seem attractive, or that the SLA were really assassins. In fact, people seem unable to imagine the existence of evil at all, unless it comes wearing evil costumes, as the Manson girls do. What people do understand, as Kant observed, is mere badness.

Therefore the trial became one about Hearst’s badness. Listening to the kind of questions the prosecution asked, you got the feeling that here was Miss Teenage America on trial, for telling the nun to go to hell, for not being a virgin, for feeling ambivalent about getting married. Some schoolgirl lies were dredged up. Quantities of school reports and friends’ opinions were introduced to show that she was independent and self-willed, that is, the type of girl who would join an SLA, instead of being ideally feminine and passive. Independence was spoken of as a moral defect; the prosecution even exerted itself to show that she was sarcastic, until the exasperated Bailey objected that his client was not on trial for sarcasm. Objection sustained. But “Did Miss Hearst ever use marijuana or other narcotics?” witnesses were asked by Browning. Objection: prosecution is trying to tell the jury about inadmissable prior offenses. Objection overruled. “Jury stunned by drug revelations,” crowed the press, relieved that the day had produced at least one sensational detail. Nobody told the jury what percentage of American teenagers smokes grass.

Advertisement

And in fact no one could really have told whether the jury was stunned or not. It appeared uncannily like a group of regular folks—necks no redder than most, faces impassive, unwrinkled polyester clothes. The government could only go on the assumption that inside them there existed the same prejudices that pervade the rest of society—against the young, the hip, the rebellious, the funky, and so on. Despite the jurors’ sanctimonious protestations that it hurt them more than it did her, the government was right about them, and perhaps no one ought to have been surprised. The surprising and distressing thing was the ease with which the government also commanded the sympathies of the young, hip, rebellious, and funky in its prosecution of Hearst. It seems a rather sinister coalition.

Considerations of badness prevailed over convincing evidence of duress, at least where this initial crime was concerned. The gun of Cinque De-Freeze seems to have been pointed at her throughout the bank episode, and the government at first suppressed a photograph showing Camilla Hall’s gun pointed at her too. On the stand, Ulysses Hall, an old prison friend of DeFreeze, gave a convincing account of a discussion of the holdup, in which DeFreeze said that because he neither wanted to kill her nor dared to let her go, his plan was to “front her off” so she’d have to stay with them. He didn’t quite trust her, he told Hall, for “though she say ‘yes’ this, ‘yes’ that, what would you say” in her situation?

In any case, the jury was instructed in effect to ignore her situation, though it was allowed to bear in mind what she did later. In theory one could view the robbery either as an effect of the kidnaping, or as an act—that is, a first cause capable of generating a further sequence of consequences, like the Mel’s Sporting Goods Store incident; an act is one of free will. If the bank robbery is taken as an act, and the judge so took it, there can be no consideration of causes, and without consideration of causes there was in fact no question of her guilt, since she was plainly in that bank with a gun in her hand. Whether the conditions of her kidnaping constituted duress became beside the point, since cause and effect are not the same thing as guilt and innocence. The judge told the jury, in effect, to ignore the defense.

An imaginative jury might have borne it in mind, though. They saw the closet, they heard the testimony about the experiences of people to whom similar things had happened. (Though one prosecution psychiatrist said cheerfully that the closet wasn’t as bad as Dachau.) There were things, however, that the jury was not allowed to see or know, for example, first, about the death threats and bombings that went on during the trial, though these seemed to bolster Hearst’s contention that there are still others out there, of whom she is afraid. (The jury eventually did get wind of this via a prosecution blunder, but so poorly did it understand the implications that one juror expressed fear as they prepared to go home that Hearst’s terrorist friends would go after them for convicting her.)

Second, the jury appears to have been heavily influenced against Hearst by hearing the so-called Tania tapes, in which she denounces her parents and affirms her love for Willie Wolfe and revolution. The judge admitted the tapes as evidence but would not admit expert testimony, based on analysis of speech patterns, that Hearst did not write the words spoken on those tapes. Dr. Margaret Singer, a University of California psychologist and well-known specialist in language analysis, was originally appointed by the court to examine Hearst and administer psychometric tests. After detailed study, Dr. Singer was prepared to testify that most of Tania’s speeches had been written by Angela Atwood, and the last by Emily Harris. This type of analysis is regularly accepted in courts to decide cases of disputed authorship, and the judge received a brief so demonstrating, but declined to hear the evidence. Bailey had to contend continually against this kind of judicial caprice. Some observers felt that in this instance the elderly judge was simply unused to female expert witnesses.

The performances of the five psychiatrists gave rise to much merriment and derision, with Browning suggesting to the jury that the opposing opinions cancelled each other, and observers predicting that here, at last, came the end of psychiatry in the courtroom. It was disturbing that the court made no distinctions in accepting the testimony of psychiatrists of widely varying professional qualifications. The court originally appointed Singer and Jolyon West, chairman of the department of psychiatry at UCLA, and two professors of psychiatry from USC and Stanford. They submitted reports, containing the coercive persuasion diagnosis, to the court itself. Eventually the defense asked West to testify because of his extensive experience with Korean war prisoners, and added Martin Orne from the University of Pennsylvania and Robert Lifton of Yale, each of whom had similar training. All of these people have distinguished national reputations, and are, one must suppose, incorruptible, unless it be by their enthusiasm for cases of this kind.

The prosecution psychiatrist Joel Fort, on the other hand, is, as one magazine put it, a free-lance courtroom witness, and is not certified in psychiatry. Up to the beginning of the trial he was equally prepared to testify for the defense. He describes himself as being into hot-line telephone therapy, was dismissed as director of a San Francisco clinic, and was described by a former California director of Public Health as someone who was “untrustworthy and not to be believed.” A man who had worked under the other prosecution psychiatrist, Harry Kozol, head of the Bridgewater Institution for the Criminally Insane, testified in court that Kozol had expressed his dislike of the Hearsts before ever seeing Patricia Hearst, saying among other things that Mrs. Hearst is “a whore [who] tries to look like Zsa Zsa Gabor”—a remark Kozol denied making.

Perhaps the judge was right in instructing the jury that psychiatric evidence is “opinion”; perhaps not. But surely if there are to be such things as disinterested expert witnesses in court it must be admitted that there are such things as expertise and disinterestedness. Here the jury, apparently incapable of making professional distinctions, seemed actually to believe the chummy Fort, whose disinterestedness may be guessed at. His bill to the government will be around $12,500; Kozol’s around $8,000. Jolyon West will charge some $1,000. (What Lifton and Orne are charging is unknown.) Fort is charging for the time it took to read a list of 274 books (some listed twice, though) in order to make himself an “expert” about brainwashing—books you might have expected an expert to have read already—and for time spent in “planning and strategy.”

Anyway the jury either didn’t understand the psychiatric evidence or didn’t believe it. Patricia Hearst was credited with free will and held to a standard of behavior more exacting than the standard the military has applied to its captured soldiers (although, when you think of it, the military conception of normal behavior can include looting and murder, and perhaps shouldn’t be taken as the standard). But where is the line which society must draw in pursuing criminal justice? As Bailey said in his summation, “How far can you go to survive?”

In a sense, all criminals are people who have been put in closets; certainly all pleas of diminished responsibility involve saying my mother, or society, or someone put me in the closet. This trial will probably do little toward deciding whether closets are to make any difference, but it may reinforce what one perceives as a general tendency in this country at present to return to the idea that the individual is responsible for his actions regardless of diminished capacity. Perhaps that is just as well; but duress is another matter, and duress was the moral heart of the case. The government was not interested in moral complexities; it wanted conviction. The judge piously instructed the jury that the government always wins when justice is done, whereas justice was the one thing no one seemed to want to bother with.

One never knows how to feel toward the victims of injustice. They become separated from us, marked by our sense of their peculiar destiny. It is hard to imagine how anything can go right for this poor heiress of ill-fortune now. In books people are enobled by tribulation, but in the real world, fear and prison just make you dull and vicious. You can’t help but wonder how any of the people whose lives have been blighted by these events can possibly transcend them.

Of course, a number of questions remain unanswered. Not until sentencing can we know the government’s disposition toward mercy. It may be that a penalty bargain will be struck in return for state’s evidence. In that case, the government would be further victimizing Hearst, placing her in a moral dilemma and possible physical jeopardy by urging that she testify against people who may have helped her. Some SLA associates—the Soliah sisters and others—are still at large. The legal status of people like the Jack Scotts, who are alleged to have been involved in harboring the fugitive Harrises and Hearst, is unclear. No one is sure whether others will be charged in the Carmichael bank robbery where a woman was killed, and for which Steven Soliah is at present standing trial; this may depend on whether additional testimony can be extorted from Hearst.

Perhaps in an effort to head her off, Bill and Emily Harris are belatedly sounding like the People Next Door. From their account in New Times1 you would find it hard to believe that these thoughtful, diffident revolutionaries were ever members of the crazy gang that murdered the innocent Foster and kidnaped Hearst. Another inside report, in Rolling Stone,2 seriously contradicts them, characterizing them as militant assassins, and both accounts are contradicted on some points by Hearst.

But the Harrises seem to have a surprising number of believers. Is it because there are two of them? Because they are married? Because they look so normal and midwestern, and do not wear evil costumes, and do talk so volubly about truth and love? “I just felt like she turned against the friends she loved and trusted,” sighed Emily over Patty’s behavior at the trial. Patty is the Enemy of the People. Says the Harrises’ lawyer, Leonard Weinglass, “She chose to go the route of wealth and power and deception. She wrongfully accused her friends and slandered her dead lover Cinque [sic], and vilified the political organization she chose to join.” But luckily for him, Patty’s credibility as a witness is damaged by her conviction, so she can’t do the Harrises much harm, and, anyway, it was Patty holding the smoking gun at Mel’s.

The Harrises do seem to lead charmed lives, or to have had, all along, a strong sense of self-preservation. William Harris has not been charged with the Hearst kidnaping; though she has testified that he was one of her abductors (in blackface), she is a convicted felon whom no one believes. The Harrises did not do the Foster murder, though, according to Hearst’s testimony, neither did Remiro and Little, who have been convicted for it; if they were around for the Hibernia Bank robbery, they haven’t been charged for that, either. When they go on trial in Los Angeles, a lot of evidence—weapons, explosives, manifestoes—that was used against Hearst will not be admitted against them because it was seized illegally. (Bailey seems to have erred in the Hearst case by trusting prosecutor Browning’s assurance that the evidence was obtained legally; Bailey therefore didn’t make routine motions to have it excluded.) The first part of the Harrises’ story in New Times was published just in time for the prosecution to learn from it that the stone figure in Hearst’s purse had been given her by Willie Wolfe, information that clinched things for at least two of the sentimental jurors. “I think she really loved Willie Wolfe,” confided one.

And, obviously, Bill and Emily were not around for the Los Angeles shootout. If they had succeeded in being arrested on the shoplifting charge at Mel’s, they would have been separated even sooner from their more dangerously visible comrades. As it stood, it was the Harrises who fingered the neighborhood where the rest of the SLA were staying. Says Emily ingenuously, “The worst part of the thing at Mel’s was that there was a parking ticket in the van that we completely forgot when we abandoned it after splitting from the store. That was how the police located the 84th Street area, where SLA members were staying.” “Yeah,” says Bill, “police agencies didn’t know that the SLA was in the LA area until Mel’s. Knowing that makes all the other things seem unimportant and the psychological burden of that has been really incredible for me.” As it is unlikely that they will receive the maximum penalty for the Los Angeles fracas, the psychological burden may be about the worst burden Bill and Emily will have to bear.

Probably people will lose interest in what happens to the Harrises. For them, for the Hearsts, for the others, innumerable ordeals are in store, but the audience has seen enough and goes home happy. Though at first the complicated plot was mystifying, all became intelligible by the end: the American system works. The rich cannot buy their way out of things. A stern lesson has been administered to terrorists. The victim is seen to have been asking for it all along. Flashy out-of-town lawyers and fast-talking shrinks have been beaten back by just plain folks. The government, like the big bad wolf, disguises its appetite for radicals beneath the lacy cap of egalitarianism, and in their pleasure at the fate of the rich snitch, the people rush to get into bed with Grandma.

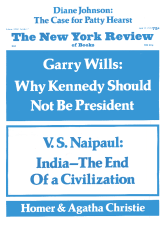

This Issue

April 29, 1976