The impending reissue in England of The Middle of the Journey so many years after it was first published makes an occasion when I might appropriately say a word about the relation which the novel bears to actuality, especially to the problematical kind of actuality we call history. The relation is really quite a simple one but it is sometimes misunderstood.

From my first conception of it, my story was committed to history—it was to draw out some of the moral and intellectual implications of the powerful attraction to Communism felt by a considerable part of the American intellectual class during the Thirties and Forties. But although its historical nature and purpose are attested to by the explicit reference it makes to certain of the most momentous events of our epoch, the book I wrote in 1946-1947 and published in 1947 did not depict anyone who was a historical figure. When I have said this, however, I must go on to say that among the characters of my story there is one who had been more consciously derived from actuality than any of the others—into the creation of Gifford Maxim there had gone not only such imagination as I could muster on his behalf but also a considerable amount of recollected observation of a person with whom I had long been acquainted; a salient fact about him was that at one period of his life he had pledged himself to the cause of Communism and had then bitterly repudiated his allegiance. He might therefore be thought of as having moved for a time in the ambiance of history even though he could scarcely be called a historical figure; for that he clearly was not of sufficient consequence. This person was Whittaker Chambers.

But only a few months after my novel was published, Chambers’s status in history underwent a sudden and drastic change. The Hiss case broke upon the nation and the world, and Chambers became beyond any doubt a historical figure.

The momentous case had eventuated from an action taken by Chambers almost a decade earlier. In 1939 he had sought out an official of the government—Adolph Berle, then assistant secretary of state—with whom he lodged detailed information about a Communist espionage apparatus to which he himself had belonged as a courier and from which he had defected some years earlier. What led him to make the disclosure at this time was his belief that the Soviet Union would make common cause with Nazi Germany and come to stand in a belligerent relation to the United States.

As a long belated, circuitously reached outcome of this communication, Alger Hiss was intensively investigated and questioned, a procedure which by many was thought bizarre in view of the exceptional esteem in which the suspected man was held—he had been an official in President Roosevelt’s administrations since 1933 and a member of the State Department since 1936; he had served as adviser to the president at Yalta, and as temporary secretary general of the United Nations; in 1946 he had been elected president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The long tale of investigation and confrontation came to an end when a federal grand jury in New York, after having twice summoned Hiss to appear before it, indicted him for perjury. The legal process which followed was prolonged, bitter, and of profound moral, political, and cultural importance. Chambers, who had been the effectual instigator of the case, was the chief witness against the man whom he had once thought of as a valued friend. He was as much on trial as Alger Hiss and his ordeal was perhaps even more severe.

At the time I wrote The Middle of the Journey, Chambers was a successful member of the staff of Time and a contributor of signed articles to Life and therefore could not be thought of as having a wholly private existence, but he was not significantly present to the consciousness of a great many people. Only to such readers of my novel as had been Chambers’s collegemates or his former comrades in the Communist Party or were now his professional colleagues would the personal traits and the political career I had assigned to Gifford Maxim connect him with the actual person from whom these were derived.

In America The Middle of the Journey was not warmly received upon its publication or widely read (the English response was more cordial) and some time passed before any connection was publicly made between the obscure novel and the famous trial. No sooner was the connection made than it was exaggerated. To me as the author of the novel there was attributed a knowledge of events behind the case which of course I did not have. All I actually knew that bore upon what the trial disclosed was Whittaker Chambers’s personality and the fact that he had joined, and then defected from, a secret branch of the Communist Party. This was scarcely arcane information. Although Chambers and I had been acquainted for a good many years, anyone who had spent a few hours with him might have had as vivid a sense as I had of his comportment and temperament, for these were out of the common run, most memorable, and he was given to making histrionic demonstration of them. As for his political career, its phase of underground activity, as I shall have occasion to say at greater length, was one of the openest of secrets while it lasted, and, when it came to an end, Chambers believed that the safety of his life depended upon the truth being widely known.

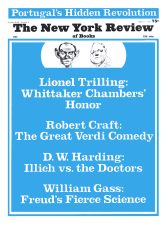

Advertisement

That there was a connection to be drawn between Whittaker Chambers and my Gifford Maxim became more patent as the trial progressed, and this seemed to make it the more credible that my Arthur Croom derived from Alger Hiss; some readers even professed to see a resemblance between Nancy Croom and Mrs. Hiss. If there is indeed any likeness to be discerned between the fictive and the actual couples, it is wholly fortuitous. At no time have I been acquainted with either Alger Hiss or Priscilla Hiss, and at the time I wrote the novel, we did not, to my knowledge, have acquaintances in common. The name of Hiss was unknown to me until some months after my book had appeared.

It was not without compunction that I had put Whittaker Chambers to the uses of my story. His relation to the Communist Party bore most pertinently upon the situation I wanted to deal with and I felt no constraint upon my availing myself of it, since Chambers, as I have indicated, did not keep it secret but, on the contrary, wished it to be known. But the man himself, with all his idiosyncrasies of personality, was inseparable from his political experience as I conceived it, and in portraying the man himself to the extent I did I was conscious of the wish that nothing I said or represented in my book could be thought by Chambers to impugn or belittle the bitter crisis of conscience I knew him to have undergone. His break with the Communist Party under the circumstances of his particular relation to it had been an act of courage and had entailed much suffering, which, I was inclined to suppose, was not yet at its end.

Such concern as I felt for Chambers’s comfort of mind had its roots in principle and not in friendship. Chambers had never been a friend of mine though we had been in college at the same time, which meant that in 1947 we had been acquainted for twenty-three years. I hesitate to say that I disliked him and avoided his company—there was indeed something about him that repelled me, but there was also something that engaged my interest and even my respect. Yet friends we surely were not.

Whether or not Chambers ever read my book I cannot say. At the time of its publication he doubtless learned from reviews, probably also from one of the friends we had in common, that the book referred to him and his experience. And then when the trial of Alger Hiss began, there was the notion, quite widely circulated and certain to reach him, that The Middle of the Journey had evidential bearing on the case. In one of the autobiographical essays in his posthumous volume Cold Friday, Chambers names me as having been among the friends of his college years, which, as I have said, I was not, and goes on to speak of my having written a novel in which he is represented. He concludes his account of my relation to him by recalling that when “a Hiss investigator” tried to induce me to speak against him in court, I had refused and said, “Whittaker Chambers is a man of honor.”

I did indeed use just those words on the occasion to which Chambers refers and can still recall the outburst of contemptuous rage they evoked from the lawyer who had come to call on me to solicit my testimony. I should like to think that my having said that Chambers and I were not friends will lend the force of objectivity to my statement, the substance of which I would still affirm. Whittaker Chambers had been engaged in espionage against his own country; when a change of heart and principle led to his defecting from his apparatus, he had eventually not only confessed his own treason but named the comrades who shared it, including one whom for a time he had cherished as a friend. I hold that when this has been said of him, it is still possible to say that he was a man of honor.

Advertisement

Strange as it might seem in view of his eventual prominence in the narrative, Chambers had no part in my first conception and earliest drafts of The Middle of the Journey. He came into the story fairly late in its development and wholly unbidden. Until he made his appearance I was not aware that there was any need for him, but when he suddenly turned up and proposed himself to my narrative, I could not fail to see how much to its point he was.

His entrance into the story changed its genre. It had been my intention to write what we learned from Henry James to call a nouvelle, which I take to be a fictional narrative longer than a long short story and shorter than a short novel. Works in this genre are likely to be marked by a considerable degree of thematic explicitness—one can usually paraphrase the informing idea of a nouvelle without being unforgivably reductive; it needn’t be a total betrayal of a nouvelle to say what it is “about.” Mine was to be about death—about what had happened to the way death is conceived by the enlightened consciousness of the modern age.

The story was to take place in the mid-Thirties and the time in which it is set is crucial to it. Arthur and Nancy Croom are the devoted friends of John Laskell; during his recent grave illness it was they who oversaw his care and they have now arranged for him to recruit his strength in the near vicinity of their country home. Upon his arrival their welcome is of the warmest, yet Laskell can’t but be aware that the Crooms become somewhat remote and reserved whenever he speaks of his illness, during which, as they must know, there had been a moment when his condition had been critical. To Laskell the realization of mortality has brought a kind of self-knowledge, which, even though he does not fully comprehend it, he takes to be of some considerable significance, but whenever he makes a diffident attempt to speak of this to his friends, they appear almost to be offended.

He seems to perceive that the Crooms’ antagonism to his recent experience and to the interest he takes in it is somehow connected with the rather anxious esteem in which they hold certain of their country neighbors. In these people, who in the language of the progressive liberalism of the time were coming to be called “little people,” the Crooms insist on perceiving a quality of simplicity and authenticity which licenses their newly conceived and cherished hope that the future will bring into being a society in which reason and virtue will prevail. In short, the Crooms might be said to pass a political judgment upon Laskell for the excessive attention he pays to the fact that he had approached death and hadn’t died. If Laskell’s preoccupation were looked at closely and objectively, they seem to be saying, might it not be understood as actually an affirmation of death, which is, in practical outcome, a negation of the future and of the hope it holds out for a society of reason and virtue. Was there not a sense in which death might be called reactionary?

This was the donnée which I undertook to develop. As I have said, the genre that presented itself as most appropriate to my purpose was the nouvelle, which seemed precisely suited to the scope of my given idea, to what I at first saw as the range of its implications. After Chambers made his way into the story, bringing with him so much more than its original theme strictly needed, I had to understand that it could no longer be contained within the graceful limits of the nouvelle: it had to be a novel or nothing.

Chambers was the first person I ever knew whose commitment to radical politics was meant to be definitive of his whole moral being, the controlling element of his existence. He made the commitment while he was still in college and it was what accounted for the quite exceptional respect in which he was held by his associates at that time. He entered Columbia in 1920, a freshman rather older than his classmates, for he had spent a year between high school and college as an itinerant worker. He was a solemn youth who professed political views of a retrograde kind and was still firm in a banal religious faith. But by 1923 his principles had so far changed that he wrote a blasphemous play about the Crucifixion, which, when it was published in a student magazine, made a scandal that led to his withdrawal from college. He was subsequently allowed to return, but in the intervening time he had lost all interest in academic life—during a summer tour of Europe he had witnessed the social and economic disarray of the Continent and discovered both the practical potential and the moral heroism of revolutionary activity. Early in 1925 he joined the Communist Party.

Such relation as I had with Chambers began at this time, in 1924-1925, which was my senior year. It is possible that he and I never exchanged a single word at college. Certainly we never conversed. He knew who I was—that is, he connected me with my name—and it may be that the report I was once given of his having liked a poem of mine had actually originated as a message he sent to me. I used to see him in the company of one group of my friends, young men of intimidating brilliance, of whom some remained loyal to him through everything, though others came to hold him in bitterest contempt. I observed him as if from a distance and with considerable irony, yet accorded him the deference which our common friends thought his due.

The moral force that Chambers asserted began with his physical appearance. This seemed calculated to negate youth and all its graces, to deny that they could be of any worth in our world of pain and injustice. He was short of stature and very broad, with heavy arms and massive thighs; his sport was wrestling. In his middle age there was a sizable outcrop of belly and I think this was already in evidence. His eyes were narrow and they preferred to consult the floor rather than an interlocutor’s face. His mouth was small and, like his eyes, tended downward, one might think in sullenness, though this was not so. When the mouth opened, it never failed to shock by reason of the dental ruin it disclosed, a devastation of empty sockets and blackened stumps. In later years, when he became respectable, Chambers underwent restorative dentistry, but during his radical time his aggressive toothlessness had been so salient in the image of the man that I did not use it in portraying Gifford Maxim, feeling that to do so would have been to go too far in explicitness of personal reference. This novelistic self-denial wasn’t inconsiderable, for that desolated mouth was the perfect insigne of Chambers’s moral authority. It annihilated the hygienic American present—only a serf could have such a mouth, or some student in a visored cap who sat in his Moscow garret and thought of nothing save the moment when he would toss the fatal canister into the barouche of the Grand Duke.

Chambers could on occasion speak eloquently and cogently, but he was not much given to speaking—his histrionism, which seemed unremitting, was chiefly that of imperturbability and long silences. Usually his utterances were gnomic, often cryptic. Gentleness was not out of the range of his expression, which might even include a compassionate sweetness of a beguiling kind. But the chief impression he made was of a forbidding drabness.

In addition to his moral authority, Chambers had a very considerable college prestige as a writer. This was deserved. My undergraduate admiration for his talent was recently confirmed when I went back to the poetry and prose he published in a student magazine in 1924-1925. At that time he wrote with an elegant austerity. Later, beginning with his work for the New Masses, something went soft and “high” in his tone and I was never again able to read him, either in his radical or in his religiose conservative phase, without a touch of queasiness.

Such account of him as I have given will perhaps have suggested that Whittaker Chambers, with his distinctive and strongly marked traits of mien and conduct, virtually demanded to be coopted as a fictive character. Yet there is nothing that I have so far told about him that explains why, when once he had stepped into the developing conception of my narrative, he turned out to be so particularly useful—so necessary, even essential—to its purpose.

I have said that he entered my story unbidden and so it seemed to me at the time, although when I bring to mind the moment at which he appeared, I think he must have been responding to an invitation that I had unconsciously offered. He presented himself to me as I was working out that part of the story in which John Laskell, though recovered from his illness, confronts with a quite intense anxiety the relatively short railway journey he must make to visit the Crooms. There was no reason in reality for Laskell to feel as he did, nor could he even have said what he was apprehensive of—his anxiety was of the “unmotivated” kind, what people call neurotic, by which they mean that it need not be given credence either by the person who suffers it or by those who judge the suffering. It was while I was considering how Laskell’s state of feeling should be dealt with, what part it might play in the story, that Chambers turned up, peremptorily asserting his relevance to the question. That relevance derived from his having for a good many years now gone about the world in fear. There were those who would have thought—who did think—that his fear was fanciful to the point of absurdity, even of madness, but I believed it to have been reasonable enough, and its reason, as I couldn’t fail to see, was splendidly to the point of my story.

What Chambers feared, of course, was that the Communist Party would do away with him. In 1932—so he tells us in Witness—after a short tour of duty as the editor of the New Masses, he had been drafted by the Party into its secret apparatus. By 1936 he had become disenchanted with the whole theory and ethos of Communism and was casting about for ways of separating himself from it. To break with the Communist Party of America—the overt Party, which published the Daily Worker and the New Masses and organized committees and circulated petitions—entailed nothing much worse than a period of vilification, but to defect from the underground organization was to put one’s life at risk.

To me and to a considerable number of my friends in New York it was not a secret that Chambers had gone underground. We were a group who, for a short time in 1932 and even into 1933, had been in a tenuous relation with the Communist Party through some of its so-called fringe activities. Our relation to the Party deteriorated rapidly after Hitler came to power in early 1933 and soon it was nothing but antagonistic. With this group, some of whose members had, like myself, been at college with him, Chambers was in fairly close contact and he kept in touch with it despite its known hostility to what it now called Stalinism. Two of its members in particular remained his trusted friends despite his involvement in activities which were alien, even hostile, to their own principles.

Although as a member of this group I occasionally saw Chambers and heard that he had gone underground, I formed no clear idea of what he subterraneously did. I understood, of course, that he was in a chain of command that led to Russia, bypassing the American Party. The foreign connection required that I admit into consciousness the possibility, even the probability, that he was concerned with something called military intelligence, but I did not equate this with espionage—it was as if such a thing hadn’t yet been invented.

Of the several reasons that might be advanced to explain why my curiosity and that of my circle wasn’t more explicit and serious in the matter of Chambers’s underground assignment, perhaps the most immediate was the way Chambers comported himself on the widely separated occasions when, by accident or design, he came into our ken. His presence was not less portentous than it had ever been and it still had something of its old authority, but if you responded to that, you had at the same time to take into account the comic absurdity which went along with it, the aura of parodic melodrama with which he invested himself, as if, with his darting, covert glances and extravagant precautions, his sudden manifestations out of nowhere in the middle of the night, he were acting the part of a secret agent and wanted to be sure that everyone knew just what he was supposed to be.

But his near approach to becoming a burlesque of the underground revolutionary didn’t prevent us from crediting the word, when it came, that Chambers was in danger of his life. We did not doubt that, if Chambers belonged to a “special” Communist unit, his defection would be drastically dealt with, by abduction or assassination. And when it was told to us that he might the more easily be disposed of because he had been out of continuous public view for a considerable time, we at once saw the force of the suggestion. We were instructed in the situation by that member of our circle with whom Chambers had been continuously in touch while making his decision to break with the apparatus. This friend made plain to us the necessity of establishing Chambers in a firm personal identity, an unquestionable social existence which could be attested to. Ultimately this was to be accomplished through a regular routine of life, which included an office which he would go to daily; what was immediately needed was his being seen by a number of people who would testify to his having been alive on a certain date.

To this latter purpose it was arranged that the friend would bring Chambers to a party that many of us planned to attend. It was a Halloween party; the hostess, who had been reared in Mexico, had decorated her house both with the jolly American symbols of All Hallowmas and with Mexican ornaments, which speak of the returning dead in a more literal and grisly way. Years later, when Chambers wished to safeguard the microfilms of the secret documents that had been copied by Hiss, he concealed them in a hollowed-out pumpkin in a field. I have never understood why, when this was reported at the trial, it was thought to be odd behavior which cast doubt upon Chambers’s mental stability, for the hiding place was clearly an excellent one. But if a psychological explanation is really needed, it is surely supplied by that acquaintance of Chambers—she had been present at the Halloween party—who traced the unconscious connection between the choice of the hiding place and the jack-o’-lanterns at the party to which Chambers had been taken in order to establish his existence so that he might continue it.

Chambers was brought to the party when it was well advanced. If he had any expectations of being welcomed back from underground to the upper world, he was soon disillusioned. Some of the guests, acknowledging that he was in danger, took the view that fates similar to the one he feared for himself had no doubt been visited upon some of his former comrades through his connivance, which was not to be lightly forgiven. Others, though disenchanted with Communist policy, were not yet willing to believe that the Communist ethic countenanced secrecy and violence. These few judged the information they were given about Chambers’s danger to be a libelous fantasy and wanted no contact with the man who propagated it. After several rebuffs, Chambers ceased to offer his hand in greeting and he did not stay at the party beyond the time that was needed to establish that he had been present at it.

In such thought as I may have given to Chambers over the next years, that Halloween party figured as the culmination and end of his career as a tragic comedian of radical politics. In this, of course, I was mistaken, but his terrible entry upon the historical stage in the Hiss case was not forced upon him until 1948, and through the intervening decade one might suppose that he had permanently forsaken the sordid sublimities of revolutionary politics and settled into the secure anticlimax of bourgeois respectability. In 1939 he had begun his successful association with Time. During the years which followed, I met him by chance on a few occasions; he had a hunted, fugitive look—how not?—but he was patently surviving, and as the years went by he achieved a degree of at least economic security and even a professional reputation of sorts with the apocalyptic pieties of his news stories for Time and the sodden profundities of his cultural essays for Life. Except as these may have made me aware of him, he was scarcely in my purview—until suddenly he thrust himself, in the way I have described, into the story I was trying to tell. I understood him to have come—he, with all his absurdity!—for the purpose of representing the principle of reality.

At this distance in time the mentality of the Communist-oriented intelligentsia of the Thirties and Forties must strain the comprehension even of those who, having observed it at first hand, now look back upon it, let alone of those who learn about it from such historical accounts of it as have been written.1 That mentality was presided over by an impassioned longing to believe. The ultimate object of this desire couldn’t fail to be disarming—what the fellow-traveling intellectuals were impelled to give their credence to was the ready feasibility of contriving a society in which reason and virtue would prevail. A proximate object of their will to believe was less abstract—a large segment of the progressive intellectual class was determined to credit the idea that in one country, Soviet Russia, a decisive step had been taken toward the establishment of just such a society. Among those people of whom this resolute belief was characteristic, any predication about the state of affairs in Russia commanded assent so long as it was of a “positive” nature, so long, that is, as it countenanced the expectation that the Communist Party, having actually instituted the reign of reason and virtue in one nation, would go forward to do likewise throughout the world.

Once the commitment to this belief had been made, no evidence might, or could, bring it into doubt. Whoever ventured to offer such evidence stood self-condemned as deficient in good will. And should it ever happen that reality did succeed in breaching the believer’s defenses against it, if ever it became unavoidable to acknowledge that the Communist Party, as it functioned in Russia, did things, or produced conditions, which by ordinary judgment were to be deplored and which could not be accounted for by either the state of experimentation or the state of siege in which the Soviet Union notoriously stood, then it was plain that ordinary judgment was not adequate to the deplored situation, whose moral justification must be revealed by some other agency, commonly “the dialectic.”

But there came a moment when reality did indeed breach the defenses that had been erected against it, and not even the dialectic itself could contain the terrible assault it made upon faith. In 1939 the Soviet Union made its pact with Nazi Germany. There had previously been circumstances—among them the Comintern’s refusal to form a united front with the Social Democrats in Germany, thus allowing Hitler to come to power; the Moscow purge trials; the mounting evidence that vast prison camps did exist in the Soviet Union—which had qualified the moral prestige of Stalinist Communism in one degree or another, yet never decisively. But now to that prestige a mortal blow seemed to have been given. After the Nazi-Soviet pact one might suppose that the Russia of Stalin could never again be the ground on which the hope of the future was based, that never again could it command the loyalty of men of good will.

Yet of course the grievous hurt was assuaged before two years had passed. In 1941 Hitler betrayed his pact with Stalin, the German armies marched against Russia and by this action restored Stalinist Communism to its sacred authority. Radical intellectuals, and those who did not claim that epithet but modestly spoke of themselves as liberal or progressive or even only democratic, would now once again be able to find their moral bearings and fare forward.

Not that things were just as they had been before. It could not be glad confident morning again, not quite. A considerable number of intellectuals who had once been proud to identify themselves by their sympathy with Communism now regarded it with cool reserve. Some even expressed antagonism to it, perhaps less to its theory than to the particularities of its conduct. And those who avowed their intention of rebutting this position did not venture to call themselves by a name any more positive and likely to stir the blood than that of anti-anti-Communists.

Yet that sodden phrase tells us how much authority Stalinist Communism still had for the intellectual class. Anti-anti-Communism was not quite so neutral a position as at first it might seem to have been: it said that although, for the moment at least, one need not be actually for Communism, one was morally compromised, turned toward evil and away from good, if one was against it. In the face of everything that might seem to qualify its authority, Communism had become part of the fabric of the political life of many intellectuals.

In the context, political is probably the mandatory adjective though it might be wondered whether the Communist-oriented intellectuals of the late Forties did have what is properly to be called a political life. It must sometimes seem that their only political purpose was to express their disgust with politics and make an end of it once and for all, that their whole concern was to do away with those defining elements of politics which are repugnant to reason and virtue, such as mere opinion, contingency, conflicts of interest and clashes of will and the compromises they lead to. Thus it was that the way would be cleared to usher in a social order in which rational authority would prevail. Such an order was what the existence of the Soviet Union promised, and although the promise must now be a tacit one, it was still in force.

So far as The Middle of the Journey had a polemical end in view, it was that of bringing to light the clandestine negation of the political life which Stalinist Communism had fostered among the intellectuals of the West. This negation was one aspect of an ever more imperious and bitter refusal to consent to the conditioned nature of human existence. In such confrontation of this tendency as my novel proposed to make, Chambers came to its aid with what he knew, from his experience, of the reality which lay behind the luminous words of the great promise.

It was considerably to the advantage of my book that Chambers brought to it, along with reality, a sizable amount of nonsense, of factitiousness of feeling and perception. He had a sensibility which was all too accessible to large solemnities and to the more facile paradoxes of spirituality, and a mind which, though certainly not without force, was but little trained to discrimination and all too easily seduced into equating portentous utterance with truth. If my novel did have a polemical end in view, it still was a novel and not a pamphlet, and I had certain intentions for it as a novel which were served by the decisive presence in it of a character to whom could be applied the phrase I have used of Chambers, a tragic comedian. I had no doubt that my story was a serious one, but I nevertheless wanted it to move on light feet; I was confident that its considerations were momentous, but I wanted them to be represented by an interplay between gravity and levity. The frequency with which Chambers verged on the preposterous, the extent to which that segment of reality which he really did possess was implicated in his half-inauthentic profundities, made him admirably suited to my purpose. If I try to recall what emotions controlled my making of Gifford Maxim out of the traits and qualities of Whittaker Chambers, I would speak first of respect and pity, both a little wry, but also of intellectual and literary exasperation and amusement.

It was not as a tragic comedian that Chambers ended his days. The development of the Hiss case made it ever less possible to see him in any kind of comic light. The obloquy in which he lived forbade it. He had, of course, known obloquy for a long time, ever since his defection from Communism and the repudiation of the revolutionary position. Even gentle people might treat him with a censorious reserve which could be taken for physical revulsion. Such conduct he had met in part by isolating himself, in part by those histrionic devices which came so easily to him, making him sometimes formidable and sometimes absurd. But the obloquy that fell upon him with the Hiss case went far beyond what he had hitherto borne, and there was no way in which he could meet it, he could only bear it, which he did until he died. The educated, progressive middle class, especially in its upper reaches, rallied to the cause and person of Alger Hiss, confident of his perfect innocence, deeply stirred by the pathos of what they never doubted was the injustice being visited upon him. By this same class Whittaker Chambers was regarded with loathing—the word is not too strong—as one who had resolved, for some perverse reason, to destroy a former friend.2

Nor did the outcome of the trial and Hiss’s conviction for perjury do anything to alienate the sympathy of the progressive middle class from Hiss or to exculpate Chambers. Indeed, the hostility to Chambers grew the more intense when the case was used by the unprincipled junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, in his notorious antiradical campaign.

So relentlessly was Chambers hated by people of high moral purpose that the newsletter of his college class, a kind of publication which characteristically is undeviating in its commitment to pious amenity, announced his death in 1961 in an article which surveyed in detail what it represented as his unmitigated villainy.

If anything was needed to assure that Chambers would be held in bitter and contemptuous memory by many people, it was that his destiny should have been linked with that of Richard Nixon. Especially because I write at the moment of Nixon’s downfall and disgrace, I must say a word about this connection. The two men came together through the investigation of Hiss which was undertaken by the Committee of the House of Representatives on Un-American Activities; Nixon, a member of the committee, played a decisive part in bringing Hiss to trial. The dislike with which a large segment of the American public came to regard Nixon is often said to have begun as a response to his role in the Hiss case, and probably in the first instance it was he who suffered in esteem from the connection with Chambers. Eventually, however, that situation reversed itself—as the dislike of Nixon grew concomitantly with his prominence, it served to substantiate the odium in which Chambers stood. With the Watergate revelations, the old connection came again to the fore, its opprobrium much harsher than it had ever been, and as discredit overtook the president, partisans of Hiss’s innocence were encouraged to revive their old contention that Hiss had been the victim of Chambers and Nixon in conspiracy with each other.

The tendentious association of the two men does Chambers a grievous injustice. I would make this assertion with rather more confidence in its power to convince if it were not the case that there grew up between Chambers and Nixon a degree of personal relationship and that Chambers had at one period expressed his willingness to hope that Nixon had the potentiality of becoming a great conservative leader. The hope was never a forceful one and it did not long remain in such force as it had—a year before his death Chambers said that he and Nixon “have really nothing to say to each other.” The letters in which he speaks of Nixon—they are among those he wrote to William Buckley3—are scarcely inspiriting, not only because of the known nature and fate of the man he speculates about but also because it was impossible for Chambers to touch upon politics without falling into a bumble of religiose portentousness. But I think that no one who reads these letters will fail to perceive that the sad and exhausted man who wrote them had nothing in common morally, or, really, politically, with the man he was writing about. In Whittaker Chambers there was much to be faulted, but nothing I know of him has led me to doubt his magnanimous intention.

This Issue

April 17, 1975

-

1

The relation of the class of bourgeois intellectuals to the Communist movement will, I am certain, increasingly engage the attention of social and cultural historians, who can scarcely fail to see it as one of the most curious and significant phenomena of our epoch. In the existing historiography of the subject, the classical document is The God That Failed, edited by Richard Crossman (New York, Harper, 1949; London, Hamish Hamilton, 1950), which consists of the autobiographical narratives of their relation to Communism of six eminent cultural figures, Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Richard Wright (“The Initiates”), and André Gide, Louis Fischer, Stephen Spender (“Worshippers From Afar”). The American situation is described in a series of volumes called Communism in American Life, edited by Clinton Rossiter (various publishers and dates), of which the most interesting are the two volumes by Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism (New York, Viking, 1957; London, Macmillan, 1957) and American Communism and Soviet Russia (New York, Viking, 1960; London, Macmillan, 1960) and Daniel Aaron’s Writers on the Left (New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961). The most recent and in some respects the most compendious record of the relation of intellectuals to Communism and the one that takes fullest account of its sadly comic aspects is David Caute’s The Fellow Travellers (London and New York, Macmillan, 1972).

↩ -

2

A psychoanalyst, Dr. Meyer Zeligs, has undertaken to give scientific substantiation to this belief in Friendship and Fratricide (New York, Viking, 1967; London, Andre Deutsch, 1967), a voluminous study of the unconscious psychological processes of Chambers and Hiss and of the relations between the two men. In my opinion, no other work does as much as this psychoanalysis in absentia to bring into question the viability of the infant discipline of psychohistory.

↩ -

3

See Odyssey of a Friend: Whittaker Chambers’ Letters to William F. Buckley, Jr. 1954-1961, edited with notes by William F. Buckley, Jr. (New York, Putnam’s, 1970).

↩