No Way is a very short novel, bare and bleak as bones. Its ominous English title is appropriate enough for its mood, except for the easy current slanginess of that phrase, mouthed by so many of us now on trivial occasions. In Natalia Ginzburg’s Italian it was simply Caro Michele (1973), the form of salutation in the letters that tell much of the story.

This story is quite ordinary, the author seems to want us to take the people as ordinary, and yet to me they appear entirely out of the ordinary, different from any society I have ever known. Not that it is news to any of us that life can be depressing, but to live in a state of such daily depression as we have in No Way seems not to be living at all. These people are in one way like people in a stupid novel, where it is depressing to think the author supposed such creatures could exist or that they would be interesting if they did. But Natalia Ginzburg is far from stupid and the novel is far from depressing to read. Perhaps it is as she has one of her characters say, “One of the rare pleasures in life is to compare the descriptions of others with our fantasies and then with the reality.”

It may even be that to her compatriots the novel is full of comic or at least pleasurable flashes of recognition. We American readers, who know only that according to The New York Times Italy ought long ago to have had its catastrophe, can compare these scenes merely with the dire and obscure political generalizations of reporters. Probably we do not know how to recognize a Roman basement apartment full of dirty socks, empty bottles, a dozen people on the floor, bad paintings of vultures and owls, and a green tile wood stove with no wood, only a rusty disassembled submachine gun in it, forgotten. Or maybe we do imagine it all too well, and also the rich publisher’s penthouse, and the suburban house with two small loathsome firs on either side of the gate.

Certainly the narrative style is not unfamiliar, this brusque, laconic, all but melodramatic understatement.

Having read the letter, Angelica got up from the chair and searched for her shoes on the rug. She wore dark-green tights and she, too, had on a blue jumper that was rather rumpled and messy because she had been wearing it since the previous day and night, which she had spent at the hospital. Her father had been operated on the day before and had died during the night.

What seems so very odd and appalling—not beyond the reach of our fantasies, to be sure, but of an extremity certainly beyond our everyday experience—is the way these people talk to one another and the way they write their letters. Of course we have been familiar in literature for a generation with the emptiness and despair of a good many outré characters, but here we must suppose that if we were Romans, reasonably good bourgeois folk, these would be our friends and neighbors, all of them.

In these passages they are not quarrelling particularly, this is just the way they talk:

“Are you willing to pay for it?”

“Yes, I’m willing.”

“I thought you were stingy. You always said you were stingy and poor. You always said you don’t have a cent and that even the bed you sleep on belongs to your wife.”

“In fact I am stingy and poor but I’m willing to rent the scale.”

* * *

“True. Now I remember. I often tell lies.”

“It seems to me you tell useless lies.”

* * *

“I have the feeling that Angelica’s marriage won’t last long. To-day no marriages last any length of time. For that matter, our marriage didn’t last very long.”

“It lasted exactly four years,” Oswald said.

“Does that seem long to you, four years?” she asked.

Their lengthy and expository correspondence seems no more unlikely than that of other epistolary novels, and perhaps Italians are given to writing such deadpan missives to one another, just as they used to talk loudly all the time in Italian, wave their arms, wear pointy shoes, and roll their eyes in that hysterical, futile, and charming manner. It is the bleak, flat recognition of the emptiness of themselves and of the others that goes beyond the stoic wastes into some other region I do not know. I feel sure it is not supposed to be funny.

She says she has had a baby and she wants to come here to show me this pretty baby. I have not answered her yet. I used to like babies but now I haven’t the slightest desire to coo over a baby. I am too tired…. If by any chance the baby of this Martorello is yours, what will you do since you don’t know how to do anything. You didn’t want to finish school. I don’t find your paintings of houses collapsing and owls in flight very beautiful.

* * *

The name of the girl I am marrying is Eileen Robson. She is divorced with two sons. She is not pretty; in fact sometimes she is very homely. Extremely thin. Covered with freckles…. I could not live with a stupid woman. I am not very intelligent but I adore and revere intelligence.

* * *

You may think it strange, but one has very minimal and odd wishes when in fact one desires nothing.

The story of No Way is sad enough. There is a lonely mother, forty-three, abandoned by her lover. Her children are indifferent and unhappy; her divorced husband, the only source of energy in all their lives, dies. Her son Michael abandons a wanton wandering girl who may have his child; the girl takes up with an indifferent publisher, then with others. A middle-aged man, poor and lazy, probably a suppressed homosexual, does kindly errands for people and sometimes comes in the evenings to read Proust to Adriana, the lonely mother. Michael gets into some obscure conspiracy, flees to England forgetting that machine gun, marries the homely American woman who turns out to be hopelessly alcoholic, and then he is murdered in some inscrutable political demonstration in Bruges.

Advertisement

Unattractive aunts and indoient, offensive servants clutter up the ugly houses and apartments. Natalia Ginzburg shows us all of them clearly and cruelly. The unhappy daughter Angelica writes to Michael (in fact Michael has said nothing at all about love),

You say that at this moment you don’t want to have to meet the eyes of the people who love you. Indeed it is hard to tolerate the eyes of people who love us at such a time, but that difficulty can be overcome quickly. The eyes of people who love us can be extremely clear, merciful, and severe in their judgments. It can be hard to confront them but in the end it can be good and helpful for all of us to face clarity, severity, and mercy.

Perhaps that is what the author means to say. Perhaps we are to imagine for them, out of her clarity and out of our mercy, feelings deeper than those they claim for themselves—or perhaps we are simply not to condemn them for living in this frozen despair. For the knowing despair, neither witty, defiant, bitter, nor surprised, seems not to be caused by Michael’s death, or by his father’s, or by their own deadly loneliness. It is a kind of weather they live in as though there were no other and no getting out of it. There are no evil people here, no really bad deeds done that might require mercy. So I suppose this is simply Natalia Ginzburg’s Italy.

It was not always like this. An earlier novel by Natalia Ginzburg, A Light for Fools (Dutton, 1957), dealing with an earlier period, makes the time of Mussolini and of the Second World War a brave era. Here there were villains and heroes aplenty, fiery characters, peasants and gentry, and real adventures. The essential elements, though, are similar, all but that fatal atmosphere. The father, who dies early on, has also been the source of energy to his family, irascible and odd, but wonderful too, despite the fact that the years of fascism which he despises have suppressed his natural strength and rage into eccentricity. His children, like the later children, are mostly useless, so are their companions, and they get killed or become fascists. There is also a pregnancy without marriage or love, but in those days a hero could miraculously appear, Cenzo Rena, with his long raincoat like a nightgown and his hat all out of shape, bringing his stores of brandy, cigars, tuna fish in oil, and the whole world’s store of knowledge and courage. He marries the girl, takes her off to his mountain castle where he fumes at the fascists, protects his beloved peasants, and dies a hero.

A Light for Fools is a marvelous tale, full of the most distinct characters and manners, shaped with the knowledge of how children are born and grow up and then die or get old. (In No Way, the mother says, “They have never been young, so how can they grow old.”) There is absolutely no moral dithering at all. The Germans are quite simply the Germans, and nobody has to wonder if he should blame himself for what the Germans did. The Germans did what Germans do. The peasants want to kill Germans, “any dirty blackguard of a German.” That view of good and evil is oldfashioned, healthy, intelligent, and perhaps quite behind us now. It was a great pleasure to come upon this novel, and upon No Way, and I intend to find the other books of Natalia Ginzburg too.

Advertisement

Touch the Water, Touch the Wind, the new novel by Amos Oz, a young Israeli writer, is an attempt to present in fiction a representation of the European background and present situation of the Israelis. A Polish teacher of mathematics and physics named Pomeranz runs away when the Germans come. His wife Stefa stays behind and is captured first by the Germans and then by the Russians. Pomeranz makes his way down through Europe to Israel and to a kibbutz on the Syrian border. Stefa manages at last to escape the service of Russia, and joins him. At the center of the book is an impressive lyric or psalm to Israel, delivered as a saving revelation to Stefa by a secret Jew in Russia.

There is no snow there, no wolves or bears, but there our Jews sow in sunshine, run, kiss, breathe in sunshine on our mountains and there they write poems or keep cats or plant avenues of trees there on our mountains, a Jewish mountain, Comrade Fedoseyeva, and it doesn’t collapse, it stands solid and high, just a Jewish mountain, as if it was the simplest thing in the world to be a Jewish mountain or a Jewish sea or forest, or even just a plain Jewish log for all the world like any other damned log, a Bulgarian log, a Turkish log, only it’s a Jewish log in a Jewish country….

Pomeranz, in his spare time, has made an earth-shaking discovery in mathematical physics about the nature of infinity. Just as Stefa joins him, the Syrians attack and the two of them make a sort of immortal pledge to the future of Israel.

Unfortunately, as it seems to me, Oz has chosen to write in that portentous baby talk of the profound but simple soul, one of the more off-putting literary conventions.

He was left to himself day and night. He thought about many different things.

* * *

Among themselves the other sheep farmers sometimes nicknamed Elisha Pomeranz “the Wizard.” But the sheep, as ever, as in bygone days, since time immemorial, silently went on dreaming.

He has some other stylistic devices: a mixed whimsy and fantasy, presumably to remind us of fables and folk tales; a gaudy overwriting,

Arcs of horror flashed across the sky, rolls of thunder chased one another, the Sea of Galilee was lit up, and from time to time a column of wounded water rose fruitlessly in a demented spasm and was shattered into foamy droplets that also surrendered and fell back into the lake.

Persistently Oz uses the rhetoric of the big statement followed by a cute little homely detail:

He could rise in the air, soar high into the night, even discard his body, by means of a change of tune. And into his worn red boots he stuffed sackcloth against the biting cold.

For yes, Amos Oz has elected to tell his story in the vein of fantasy. When Pomeranz is captured by the Germans, he escapes by levitation, like somebody in a Chagall painting. And Stefa is not simply in Russian service, she is head of Soviet Intelligence. Thus each crucial event of the story is fobbed off into what appear to me most inept bits of foolish and obscure legerdemain—to me this seems oddly and frivolously cruel, considering what was available to real people in similar circumstances. Many of these bits of fantasy, or “symbolism” if you will, are unbelievably tasteless, as is the irrelevant sadism, sexual at times, and also the attempts at humor, no better than tags. The presence or thought of Germans evokes always pork fried in pork fat, and so on.

And I hate to write it out, but the Pomeranzes’ apotheosis is accomplished by having the earth envelop them in this eye-averting manner: “The topmost crust of earth yielded in the moist blindness with rippling spasms at the wetness of the warm virginal lips and they were slowly drawn inside. For a moment longer the slit quivered, then relaxed and enfolded them in a silent embrace of unbelievable tenderness.” The translation is by Nicholas de Lange in collaboration with the author.

Surely the subjects that the Master Race has given us in our century are so difficult and painful that they may well be, as many have said, impossible for art. We might almost concede this, were it not for Tadeusz Borowski, Elie Wiesel, and a few others. Many have failed and especially in fantasy and fable. There can be no doubt that Amos Oz’s heart is in the right place, but in this book everything else seems miserably wrong.

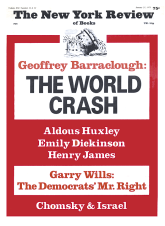

This Issue

January 23, 1975