Chance finds have played a significant part in revolutionizing the study of New Testament origins and the early Church. It was the German scholar Karl Holl, for instance, who in 1933 discovered the first manuscript texts within the Roman Empire of the sayings of the Persian heresiarch Manichaeus among the stock-in-trade of a Cairo antique dealer. Holl had been correcting proofs of an edition of the Church father Epiphanius, and he had just reached the latter’s description of the tenets of the Manichaeans the night before. He spotted the key phrase, “And now the Illuminator said…” on the top line of a discolored and waterlogged papyrus which the dealer brought out for his inspection. He bought the papyrus. From now on, the Manichaean sect to whom St. Augustine had adhered for nearly ten years could speak for themselves and not through the mouths of their opponents.

Professor Morton Smith tells of a similar stroke of luck. Both his books, one popular and the other a scholarly treatise, seek to prove that the eighteenth-century manuscript he came upon in the monastery library of Mar Saba in the Judaean desert is not only a record of a hitherto unknown letter of Clement of Alexandria (flor. 180-200), but throws a new and sensational light on the character of Jesus’ ministry.

The story which he unfolds in The Secret Gospel is a splendid one. In 1958 he was revisiting the Mar Saba monastery after an interval of seventeen years. Nothing seemed changed. At the Orthodox Patriarchate at Jerusalem he found his old friend Father Kyriakos was as genial as ever. A twenty minutes’ taxi drive brought him to the monastery where he was met by the Archimandrite, but electricity had wrought havoc with the mystic beauty of the six-hour liturgy, and he found himself spending his time in the monastery library locating, reading, and cataloguing the manuscripts. Soon he noticed that old manuscript material had been used for bookbinding, and near the end of his stay he was looking at a tiny handwriting which had been used in this way. It began, “From the letters of the most holy Clement, the author of the Stromateis. To Theodore.” It went on to praise the recipient for having silenced the Carpocratians.

Smith knew enough about early Church history to realize that the Clement of his text must be Clement of Alexandria, who flourished as a Christian teacher in that city from 180-200, and that one of the heretical sects which he refuted was the Carpocratians. They believed that sin, and in particular sexual sin, was the means of salvation, and this outraged Clement. Only a page and a half of text survived, but this was enough to excite Smith’s interest. He read the remainder with increasing incredulity. Then he photographed the manuscript and with the help of the Israeli scholar Dr. Gershom Scholem began to transcribe and study it at leisure. What he read put even the discovery of a hitherto unknown letter of Clement in the shade.

The letter spoke of secret teachings of Jesus reserved for a special circle of his followers and of a Secret Gospel written by Mark, read in the Church at Alexandria “only to those who are being initiated into the great mysteries,” but the Carpocratians had managed to obtain a copy and use it for their own nefarious purposes. Clement then quotes a passage from the Secret Gospel. This records a miracle by Jesus of raising a rich young man from the dead after the fashion of the raising of Lazarus. The scene takes place at Bethany. Jesus is met there, it is stated, by “a certain woman, whose brother had died.” She begs Jesus’ help. The disciples rebuke her, but Jesus “being angered, went off with her into the garden where the tomb was.” A great cry is heard from the tomb. Jesus rolls away the stone from the door of the tomb, seizes the young man’s hand and raises him. The young man comes forth, “looked upon him, loved him,” and beseeches him that he might be with him. Jesus stays with him and his sister for six days and instructs him in what to do. Then, “in the evening the youth comes to [Jesus] wearing a linen cloth over [his] naked [body]” and Jesus teaches him that night “the mystery of the kingdom.” Then he arises and returns to the other side of the Jordan. Clement’s “true explanation” of the text in accordance with “true philosophy” breaks off a few lines later, before it has begun.

At the lowest estimate, this was an extremely interesting find. The manuscript itself was a relatively recent copy of a much earlier document, but the initial reaction of scholars was that it was certainly exciting and could be genuine. The attitude of Arthur Darby Nock, the greatest classical scholar since Theodor Mommsen, was characteristic. “It does sound like Clement; this is too much. It must be something medieval; fourth or fifth century, perhaps.” Smith, however, was not to be put off. From then on the document was never far from his thoughts. In the course of the long and detailed analysis of the text and comparison with Clement’s vocabulary, which he lays out in masterly style in Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark, he established with as near certainty as can be that the letter is by Clement. Indeed, it is difficult to see the hand of a forger. The Carpocratians were a comparatively short-lived sect, originating with an Alexandrian Christian teacher, Carpocrates, about AD 130, prospering through the second century but being almost extinct by the time Origen wrote his refutation of the Platonist critic of Christianity, Celsus, in 248. No one would want to bother about them after that.

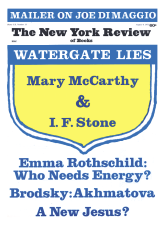

Advertisement

The letter must, therefore, have been composed sometime before that date, and in that case by whom else but Clement? Moreover, the possession of “secret gospels” by otherwise orthodox Christian communities was not unknown at the end of the second century AD, a point which Smith could perhaps have emphasized more. In circa 200 we find the relatively small Church at Rhossus in the Gulf of Issus (in southeastern Turkey) being taken to task by Bishop Serapion of Antioch for using an apocryphal “Gospel of Peter” at their services (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, vi: 12.2). It was the quite sudden emergence of the urban episcopate, exercising authority from big centers such as Antioch, Alexandria, Ephesus, and Rome, as the normal form of Church government at this period that enforced a uniform canon of Scripture on the Churches and ousted the apocryphal Gospels. Clement was writing in the 180s and 190s, just before Bishop Demetrius of Alexandria got himself properly established; and that the Church of Alexandria should possess a Secret Gospel allegedly composed by its founder, Mark, at this period is not altogether surprising.

The author, however, has not been content to record an exciting find that throws light on the hair-line difference between “orthodox” Gnosticism represented by Clement and heretical Gnosticism represented by Carpocrates and his followers in Alexandria in the period 180-200. For Smith, the secret document itself is a genuine document, a “new element in the history of the text of Mark.” Clement had pointed out to his friend Theodore that the passage he quoted came in between words in the ordinary Gospel: “and they were in the road going up to Jerusalem” and “And James and John came to him,” i.e., it followed the first phrase in Mark 10.32 and replaced Jesus’ prophecy of his trial and death in Jerusalem (Mark 10.33-34).

He had claimed, however, that the reference to “the nakedness” of the youth was a Carpocratian interpolation. Accepting the Secret Gospel as genuinely Markan, the author argues that the “mystery of the kingdom” wherewith Jesus instructed the youth was a baptism of His spirit effecting entrance of the kingdom. This was a water baptism administered by Jesus to chosen disciples singly and by night, and, apart from immersion, it consisted of other unknown ceremonies of a magical character. “The disciple was possessed by Jesus’ spirit and so united with Jesus. One with him, he participated by hallucination in Jesus’ ascent into the heavens; he entered the kingdom of God, set free from the laws ordained for and in the lower world. Freedom from the law may have resulted in completion of the spiritual union by physical union.” The libertine element found in the Carpocratian Gnostics may have a serious claim to be part of the genuine early Christian tradition.

If this were true, most of us would have to revise our views about the Gospel story of Jesus’ ministry. The Rabbinic Jewish charges echoed in Celsus’ anti-Christian diatribe, that Jesus was a magician, and not even a very efficient one, might command some credence. The relationship between the Church and the Gnostics in the second century would indeed be opened up once more to new and exciting research. But Christianity as the religion of a large part of the human race would hardly remain unscathed, and this is not putting it too high.

Moreover, Smith’s ideas, the fruit of years of literally living with the subject, are not to be dismissed out of hand. The language of the Secret Gospel is synoptic and Markan in character. Jesus’ emotion, his “anger” is an obvious point. The story is paralleled by John’s account of the Raising of Lazarus, but it also bears some resemblance to Mark’s earlier account of the raising of Jairus’ daughter (Mark 5.35-43). The instruction allegedly given by Jesus to the young man after his restoration to life “wearing a linen cloth (sindon)” finds a parallel in the curious reference in Mark 14.51-52 about the young man “having a linen cloth cast about his naked body,” who was with Jesus in Gethsemane. This passage has never been explained satisfactorily. In my mind it provides the strongest argument in favor of the author’s view that Jesus was performing a baptism in Gethsemane after partaking in a solemn Paschal meal with his disciples and was surprised in the act by the High Priest’s soldiers.

Advertisement

If this were the true explanation, however, it would mean the rejection of the rest of the Markan account, vivid in its precise description of the agony in the garden, especially its connotation with Jesus expiating the sins of His people and dying the death of a martyr, as it was believed by Jews in the first century AD that the prophets of Israel had died. Moreover, Smith seems greatly to overemphasize the existence of a magico-libertine element in early Christianity. There are traces of this. One finds them in the well-known Pauline description of some Christian practices in Corinth (I Cor. 5.2) and in Jude (circa 80-90), where they are associated with misuse of the Christian sacramental meal (agape); but the remainder of the list of New Testament references which the author has compiled is not convincing. Wrong faith as well as wrong morals were liable to be the “cause of shipwreck” to prominent would-be Christians, and it is interesting that at Corinth itself libertinism was not apparently a major problem in circa 100, the date when I Clement was written.

There was lack of discipline and jockeying for position but not immorality. A decade later, Ignatius of Antioch, a sworn enemy of sectaries, castigates various Jewish Docetists for denying the human ministry of Christ and for holding beliefs that made the martyrdom that he sought for himself ridiculous, but not for antinomian practices. Similarly, Polycarp’s denunciation of Marcion as “first-born of Satan” concerned his beliefs and not his morals. Indeed the idea that the existence of a libertine element in Christianity was a cause of persecution in the second century is misconceived. The Christians were persecuted because they fell outside the normal categories of religious life in the empire. They denied the gods of the Greco-Roman world worship, and they were not Jews. They were thus “atheists” and could be held responsible for various manifestations of divine displeasure, such as floods, earthquakes, and disease. It is a curious fact that the more libidinous Gnostic sects of the second century never seem to have been persecuted, because their members found no difficulty in sacrificing to the gods while keeping fast the secret of their salvation (see Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, iv. 7.7).

Moreover, if the Secret Gospel is as early as Smith suggests, one might have expected to find traces of it in second century literature, especially that emanating from Alexandria or in use there. Today we know that at least down to 140-150 there was a strong Jewish-Christian element in Alexandria that was using gospels such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel According to the Hebrews, and the Gospel According to the Egyptians. All these are quoted in Clement’s Stromateis, and material used in Thomas is to be found in orthodox works such as the second-century sermon preserved as II Clement and also perhaps in I Clement. But not so the Secret Gospel. Clement of Alexandria’s letter is the first mention of it. It might perhaps be argued that it falls into the same category of noncanonical yet non-Gnostic works which were circulating in Egypt in the second-century as the “Unknown Gospel,” published by T. C. Skeat in 1935. This also had Johannine as well as synoptic overtones. It may indeed be claimed as yet another independent tradition of Jesus’ life and ministry, and this is its real importance. With Thomas and the Pauline agrapha, the Unknown Gospel, the Synoptics, and John, no one today can claim that our knowledge of Jesus is derived only from one set of sources, for these texts span the Aramaic and the Greek-speaking worlds. The Markan Secret Gospel is another link in the chain.

Professor Smith’s labors have not been in vain. If one denies his claim that Clement’s authorship of his text “has consequences for the history of the early Christian Church and for New Testament criticism that are revolutionary,” he raises a number of interesting questions. Did other big Churches in the second century possess their Secret Gospels? How wide, therefore, was the divide between Orthodox mysteries and Gnostic mysteries? And regarding the problem of baptism by Jesus himself, it is surely reasonable to believe with the author that rites so deeply characteristic of early Christianity must have had an origin in Jesus’ own practice. It might have been better to stop here, with raising questions rather than seeking outright answers. There is a danger in living too long with a favorite discovery. The temptation to plumb the depths of the Markan Gospel has proved irresistible, and, one might say, fatal. One returns to A. D. Nock’s comment, “But, I say, it is exciting. You must do it up in an article for the [Harvard Theological] Review.” Yes, but not two whole books!

This Issue

August 9, 1973