In the Thirties those who came from the upper middle class and who had been to Public Schools and the old universities were easily drawn toward communism because of the discipline, the training for leadership, the team spirit and elitism at those places. To some Marxism was for a time a scripture, and not having met anyone in the working class up till then, they tried guiltily, masochistically, and idealistically to get in touch with them, often making absurd declarations of feeling inferior. I was brought up very differently. I had been to school with working-class boys and girls. My parents and relations, my grandfather the bricklayer, my eccentric great uncle the cabinetmaker, my mother the shop girl, and my father the errand boy and shop assistant in Kentish Town, had belonged originally to this class.

Marxism as a dogma could have no appeal to me, but as a way of analyzing society and of presenting the interplay of class and history, it stimulated. The fundamentalism and the totalitarian consequences of Marxism were naturally repugnant to one like myself who had been through this mill in a religious form. It would be impossible for me to become a communist or a Roman Catholic after that; and, in any case, I was constitutionally a nonbeliever. Rarely have the active politicals had a deep regard for imaginative literature. Writers are notoriously given to ambivalence and live by giving themselves to the free mingling of fact and imagination.

So although when the Spanish Civil War came I was ardent for the Popular Front, I was much less interested in the “People” than in the condition of individual people. I was particularly concerned with their lives and speech. In their misleading sentences and in the expressive silences between would lie the design of their lives and their dignity. Sometimes ordinary speech is banal, and it is always repetitive, but, if selected with art, it could reveal the inner life, often fantastic, concealed in the speaker. This was the achievement of Henry Green in novels like Living and Back, and in Hemingway’s best stories. Up till now in English literature the “common” people had been presented as “characters,” usually comic. I had a curious conversation with H. G. Wells about this. I asked him to tell me about Gissing, who had taken his working-class and lower-middle-class people seriously, so that to my mind he was closer to the Russian tradition than ours. Wells began, in his sporty way: “The trouble with Gissing was that he thought there was a difference between a woman and a lady, but we all know there is no difference at all.”

But when I asked if it were possible to present, say, a lower-middle-class man or woman seriously and not as a comic character, he reflected and said “No.” My opinion was and is that it is, of course, possible; and that the essence of comedy is not funniness but militancy. I have rarely been interested in what are called “characters,” i.e., eccentrics; reviewers are mistaken in saying that I am. They misread me. I am interested in the revelations of a nature and (rather in Ibsen’s fashion) of exposing the illusions or received ideas by which people live or protect their dignity. On the other hand, in the preoccupation with common speech which I suppose I owe to my storytelling mother and to listening closely to Spaniards and others abroad, I did not follow more than I could help the documentary realism that was fashionable in the Thirties. The storyteller either digests or contemplates life for his own purposes. It is a flash that suddenly illuminates and then passes.

I write this to explain how I came to write the story called “Sense of Humour,” the first one of mine to make a stir and give me what reputation I have as a writer of short stories. It has appeared in dozens of anthologies and has been broadcast in many languages. The tale had long been in my mind. I had written two or three versions, including one long explanatory one in the third person. None of these seemed right to me. They suffered from the vice of exposition or explanation. I put them aside and eventually saw there was another method; it is pretty obvious, but it had not occurred to me. A now forgotten Welsh writer, Dorothy Edwards, had written a story, in the first person, in which a character unconsciously reveals his obtuseness by assuming an air of reasonableness and virtue; and, in Hemingway, I found the vernacular put to similar use. The words spoken were so arranged as to disclose or evoke silently the situation the people were trying in their awkward way to conceal.

The main source of my tale was the commercial traveler I had met in Enniskillen ten years before, who took his girl for rides in his father’s hearse. My task was to make him tell his fantastic tale as flatly and meanly as possible, and to see his life through his eyes alone. The tale was written almost entirely in dialogue. I had little recollection of my original but I had known many salesmen of his kind, in whose minds calculation plays a large part.

Advertisement

I have often been asked to explain the tale; some people found it shocking and cruel, others poetic, others deeply felt, others immoral and irresponsible, others highly comical. The most intelligent interpretations came from French and German critics, thirty-five years after it was written. (I am pretty sure that although I am often described as a traditional English writer, any originality in my writing is due to my having something of a foreign mind.) My own suspicion is that the tale is a “settling” of my personal Irish question; and I am certain that if one is writing well, it is because one is at a point where one is able to define things hitherto undefined in one’s own mind or even unknown to one until then.

I am more interested in the question of the “foreign” strain. Questions of class were very important in the Thirties and in giving my uncouth character a voice I was consciously protesting against the dominance of the voice of what is called the high bourgeois sensibility. My narrator was not a “character”—in the traditional sense—though he was extraordinary. The world he lived in was one of the vulgar push and self-interest that were changing the nature of English society. In the next twenty years one would see that England was packed with people like him and his rootless friends.

His emergence as a type is commonly misunderstood by literary critics who, owing to the stamp that Dickens and Wells put upon him in their time, have thought of the lower middle class or petty bourgeois as whimsical “little men.” But in this century all classes have changed and renewed themselves; they have certainly released themselves from the cozy literary categories of the nineteenth century and carry inside them something of the personal anarchy of unsettled modern life. My own roots are in this class and I know it like the palm of my hand. (The standard view that it is inevitably Fascist is crude and untrue.) In the writing, American influence—particularly of Hemingway—is clear; and from both a literary point of view and a social one this was natural.

I do not write this to claim any great merit for the tale. I am clinically concerned with it as something new in my own life which was brought about by the times and the emancipation a new marriage had given me. I had become real at last. I worked for months on this story, for in writing there is a preliminary process of un-writing, and ideas are apt to be dressed in conventional literary garb in the first instance. (In considering the character of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot, Dostoevsky seriously considered Mr. Pickwick as a starting point.) A good story is the result of innumerable rejections. Also, very often, of rejections that are more painful.

“Sense of Humour” was turned down by all likely publications in England and America. I put it away with the feeling that I had made one more bloomer. Then, after a year or two, John Lehmann’s New Writing appeared and he published it. I got £3 for the story. I cannot say that I woke up to find myself famous but I had modestly arrived. It is a pleasant and also curious experience. I loved being congratulated, especially publicly in restaurants. One admirer, only an acquaintance at the time, and a comically shamefaced womanizer, begged me to introduce him to the girl in the story, for whom he had fallen. I had drawn her from several models, but chiefly from a girl I had glanced at behind the desk of an Irish hotel. The important thing for me was that the story woke me up. It led me on to “The Sailor,” “The Saint,” and “Many Are Disappointed,” which became far better known.

When I was writing for the New Statesman in these early days, David Garnett was the literary editor, and in one of our talks about writing novels he said that when one could not get on with a book one should create an extra difficulty. That did not help me because difficulty of all kinds surrounds me in writing and writing has always seemed to me the result of being able to throw innumerable temptations from the mind. I have an impatient character; for every page I write there are half a dozen thrown away. The survivors are crisscrossed with deletions. I went through a long period of talking to myself when I went for a walk and again and again I would catch myself saying, with passion, two words: The End. Not necessarily the end of a story or an essay, but the end of the confusion, the end of the statement or sentence. My weakness for images was caused by the poet’s summary instinct. I have had to conclude that I am a writer who takes short breaths and in consequence the story or the essay have been the best forms for me and early journalistic training encouraged this.

Advertisement

Because of its natural intensity the short story is a memorable if minor literary genre. There is the fascination of packing a great deal into very little space. The fact that form is decisive concentrates an impulse that is essentially poetic. The masters of the short story have rarely been good novelists: indeed the short story is a protest against the discursive. Tolstoy and Turgenev are exceptions, but Maupassant wrote only one novel of any account: Une Vie. Chekhov wrote no novels. D. H. Lawrence seems to me more penetrating as a short story writer than as a novelist. An original contemporary, Jorge Luis Borges, finds the great novels too loose. He is attracted to Poe’s wish for the work of art one can see shaping instantly to the eye. The form attracts experiment. It is one for those who like difficulty, who like to write 150 pages in order to squeeze out twenty.

At the time of the Spanish war when I had to go to a protest meeting in an industrial town, one of the speakers interested me. I wrote two pages about her and gave up. From year to year I used to look at this aborted piece. No difficulty: no progress. Suddenly, after twenty years I saw my chance. When one is making a speech one is standing with one’s body and life exposed to the audience: the sensation is frightening. Write a story in which a woman making a speech in her public voice is silently telling by the private voice her own life story while she declaims something else. To do this was extremely difficult. One learns one’s craft and craftmanship is not much admired nowadays, for the writer is felt to be too much in control; but, in fact, the writer has always, even if secretively, to be in control. And there is the supreme pleasure of putting oneself in by leaving oneself out.

I have written six volumes of short stories and many others that have never appeared in book form. I am surrounded, as writers are, by the wreckage of stories that are half done or badly done. I believe in the habit of writing. In one dead period, when I thought I had forgotten how to write, I set myself a well-known exercise which Maupassant, Henry James, Maugham, and Chekhov were not too grand to try their hands at. It is the theme of the real, false, or missing pearls. I was so desperate that I had to say to myself, “I will write about the first person I see passing the window.” It happened by ill luck (for I thought I knew little about the trade) to be a window cleaner.

Whatever may be thought of this story—I myself do not like the end which should have been far more open—it revealed to me as I wrote two things of importance in the creative imagination. The first: there is scarcely a glint of invented detail in this tale; it is a mosaic that can be broken down into fragments taken from things seen, heard, or experienced from my whole life, though I never cleaned a window or stole a pearl. The second thing—and this is where the impulse to write was felt and not willed—is the link with childhood. To write well one must never lose touch with that fertilizing time. And, in this story, some words of my mother’s about her father came back to me. He was a working gardener and coachman. It was part of the legend of her childhood that one morning his employer’s wife called, “Lock the drawers: the window cleaner is coming.” I did not write about my grandfather but the universal preoccupation with theft came brimming into my mind.

The Irish, the Italians, the Russians, and the Americans have an instinctive gift for the short story. Alberto Moravia once told me that the Italian successes in this form and their relative failure in the novel are due to the fact that the Italian is so conceited that he dare not look long and steadily at his face in the mirror. I would have thought that the gift is due to the Italian’s delight in the impromptu. Frank O’Connor used to say that the form is natural to societies where the element of anarchy is strong and the pressure of regard for society is weak. In English literature we indeed had to wait for the foreign rootlessness and rawness of Kipling before we had a master. Once discovered, this quickly appeared in Saki, in D. H. Lawrence, in the pastorals of A. E. Coppard and T. F. Powys, in Walter de la Mare, Max Beerbohm, H. E. Bates, Elizabeth Taylor, Frank Tuohy, James Stern, and Angus Wilson. Later starters, we have done well.

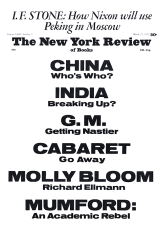

This Issue

March 23, 1972