A document has just reached the West which reveals with remarkable vividness the personality of Vladimir Bukovsky, the Russian dissenter who was sentenced on January 5 in Moscow to a twelve-year term of prison and exile for alleged “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” with subversive intent. Although the trial had taken nine months to prepare, it lasted only one day and was closed to independent observers and journalists.

The document is a 3,000-word open letter to the Washington Post, which the Post has not published. It was written by Mr. Bukovsky in June, 1970, five months after his release from a labor camp and nine months before his arrest last March. Until now the letter has been known only from a brief summary in the typescript Moscow journal A Chronicle of Current Events. A condensed translation follows.

—Peter Reddaway

Dear Editor,

In your issue of 17 May, 1970, you published my interview with an Associated Press correspondent, Mr. [Holger] Jensen, in which I recounted details of my life and of what I saw in the Leningrad special psychiatric hospital in 1963-65 and in the ordinary-regime camp at Bor Settlement in Voronezh Region in 1967-70.

On 9 June, 1970, I was summoned by citizen Vankovich, Assistant Prosecutor of Moscow City, to Novokuznetskaya Street 27, room 8. I consider it my duty to convey to you the content of the conversation.

Vankovich: Your interview has been published in the Washington Post. Have you read it?

I: No, I haven’t, as that paper is not sold in the USSR.

Vankovich: Understand me correctly, I simply have to establish whether the interview is by you and whether the correspondent recorded your words correctly. Maybe it was he who was responsible for the libels on the Soviet system which appear.

I: Speaking for myself, I did not libel the Soviet system, and I can repeat to you what I said then. But I would like to point out that this is simply an act of good will on my part and that I have a perfect right not to talk with you. [Mr. Bukovsky repeats what he told Mr. Jensen.]

Vankovich: Well, now read a translation of the interview. [Then, after Bukovsky has read it:] Does that correspond to what you said?

I: Generally speaking yes, although your translation is poor. The translator has, for example, translated the word “dissident” as “sectarian”….

Vankovich: Here you say that in 1960 [at the age of 17] you were forbidden to study. How did that happen?

I: The ban was openly stated to my parents and myself in the committee offices of the Moscow City Communist Party…. And besides that, when in 1961 I was refused reinstatement in Moscow University on the insistence of the committee of the Young Communist League, this was explained by the statement that my character “did not correspond to the character of a Soviet student.”

Vankovich: Now what about these punishments [in the Leningrad hospital]? What are these drugs?

I: The drug which produced fever and a temperature is called sulphazin, the other—a soporific—is aminazin.

Vankovich: What? Were these administered in your presence? As punishment to healthy people? For what misdemeanors?

I: Yes, they were. For example, for calling a psychiatrist a “butcher in a white coat” you would probably get an injection of one of those drugs. I can give you examples.

Vankovich: But do you realize the significance of your sentence about people who “are turned into vegetables”? Do you realize who profits from that? Most people in America don’t know what aminazin and sulphazin are. For them those are just terms. But the sentence about vegetables—that’s easy to understand.

I: I don’t know if it’s best to call the victims’ condition that of vegetables or, for example, animals. But I do know that these drugs produce stupefaction, convulsions, and other awful things, and that they are used as punishments in that hospital.

Vankovich: So in your opinion one should not treat the mentally ill at all?

I: I’m talking not about the mentally ill but about healthy people who have been put in hospitals for their political beliefs and actions.

Vankovich: But who’s putting healthy people in hospitals? Where have you observed that?

I: Well, have you heard, for example, that Doctor of Biology Zhores Medvedev, whose friends are eminent Soviet scientists and writers, has been forcibly hospitalized, although he has never needed psychiatric help? [This had happened ten days previously.] I could give you other examples. In my view, these are fascist methods.

Vankovich: Well look, it’s like this. His friends are not psychiatrists and can’t know whether or not he’s healthy. People can fall ill suddenly. Anyway you’re still young…. How can you know what fascism is?

I: I have one friend whose spine was broken on the rack while he was being tortured in Stalin’s dungeons. Is that, in your opinion, fascism?

Vankovich: What’s the relevance of that? A rack, tortures? What can you know of that? You weren’t alive then. In fact, I wonder whose side you’d have fought on. Yes, I wonder a lot. People like you were our enemies in the war.

I: I think I’d have chosen correctly which side to be on so as to fight for the interests of the Russian people.

Vankovich: I wonder. With you it’s all words and posturing. When action is needed people like you don’t have the courage.

I: I had enough courage to act in defense of my illegally arrested friends [in 1967, when organizing a demonstration], although I knew that I’d get three years. Isn’t that action?

Vankovich: What’s three years? That was not war. In the war we risked our lives. That was action.

I: Tell me, please, how old are you?

Vankovich: Forty-five.

I: So in 1949 you were twenty-four? Well, how did you react to the illegal arrests, the wave of terror which swept over the country then? Did you keep silent?… And now you hold forth about courage.

Vankovich: That is all irrelevant. We’re talking about your interview. You were asserting just now that you had been in a camp. It wasn’t a camp. We don’t have camps.

I: In philology there’s the concept of a euphemism. First the camps were called camps, then colonies, and now they’re institutions. You know, it’s like the way the toilet was first called a necessity [nuzhnik], then that became embarrassing and it was called a water closet, then it became a lavatory, and so on.

Vankovich: How do you know how many labor colonies there are in Voronezh Region? [Bukovsky had reported there were ten, with some 1,500 prisoners in his own.]

I: I was in the regional prison hospital in Voronezh City, where sick prisoners from all the camps of the Voronezh Region are kept.

Vankovich: There, you see, you got qualified medical aid.

I: That happened once, when I had had a temperature for several months. Generally speaking, the medical aid was very bad. The doctors usually declared that ill people were faking. One prisoner called Aralov died of a heart attack on the steps of the medical department. They had declared him a faker and refused to give him validol [the drug he needed]. Does a fact like that interest you?

Vankovich: No…. Who were you with in that institution?

I: Petty thieves and hooligans. There was, for example, one person from the countryside who had got three years for stealing three buckets of oil cake.

Vankovich: That can’t be so. He must have got less.

I: I know him well. The whole camp knew his story. The judge had told him at his trial that he was giving him one year for each bucket.

Vankovich: But that can’t be so. Here’s the Criminal Code, have a look yourself.

I: In that case he was wrongly sentenced. And you, as a procurator, should investigate his case and appeal against the sentence. I’ll give you his name. Seek him out. After all, it’s your duty to ensure the observation of legality.

Vankovich: No, it’s not my duty. He doesn’t live in Moscow…. How did they feed you?

I: The normal rations were 650 grams of bread and 13 of sugar per day, plus, for breakfast, porridge oats, for lunch, usually cabbage soup then porridge, and for supper, porridge or soup (very thin). About once a week mashed potato. Occasionally, for breakfast or supper, soup made from fish bones. We were meant to get 50 grams of meat a day, but we never saw any at all.

Vankovich: But you don’t realize that you were being paid for by the state.

I: Not only were we not being paid for by the state, but each month we had half our pay deducted for our upkeep…. You’re a procurator. Why don’t you want to find out the facts, punish the guilty, and thus improve conditions for the prisoners?

Vankovich: But they’re criminals. They’re not in a health resort. They’ve been deprived of their freedom by sentence of a court, quite legally.

I: The courts sentenced these people to deprivation of their freedom, not deprivation of their health. The severity of their punishment does not correspond to their crimes.

Vankovich: I am obliged to warn you that your interview contains libels on the Soviet system and that we have the right to call you to account under Article 190-1 of the Criminal Code if you don’t stop your activities.

I: You consider that the facts presented in that interview do not correspond to reality?

Vankovich: Yes.

I: In that case let me collect together all the people who can confirm the facts. I am in contact with them. Do you want them to testify?

Vankovich: No, no, it’s not necessary.

I: In that case, where’s the libel?

Vankovich: I do not intend to explain it to you in detail.

I: But then your assertions are empty words….

Vankovich: You and I are on different sides.

I: Personally, I am on the side of the law. If you, a procurator, are on the other side, then that’s very sad.

Vankovich: I am officially warning you that at any time we can arrest you for the libels in your interview.

I: What’s that, a threat? There’s no point in threatening me. I’m not afraid of that. If one trial and one final speech of mine [i.e., at his 1967 trial] are not enough for you, there will be two, and after my release there will be fresh material for another interview.

Vankovich: So you won’t stop your activity?

I: Certainly not. It’s my moral duty to my comrades from the camp. And to those of my friends who are still there.

[Finally Mr. Bukovsky ends his letter:]

This record of my conversation will serve to show how cases under Article 190-1 are organized in our country; also, in the event of my arrest, you will know all the details behind it.

In due course, however, the KGB opted for Article 70, or “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” It thus prepared the ground for the penalty imposed on Mr. Bukovsky on January 5 to be not three years but twelve, and the conditions of his confinement to be much more severe than those he experienced in Voronezh Region from 1967 to 1970.—PR

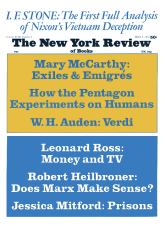

This Issue

March 9, 1972