Newtown Town Hall

March 18, 1971

Newtown, Connecticut, where this talk was given, borders on Danbury, where the Berrigans are in Federal Prison.

Brothers and sisters. Fellow Democrats. Fellow Americans. Last summer, when the FBI finally captured Father Daniel Berrigan after he had successfully avoided them for four months in the underground, one of the FBI men is said to have muttered under his breath, as he put the shackles on, “Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam,” the Jesuit motto which means “To the greater glory of God.” Although our notion of the average FBI man does not include a fluent knowledge of Latin, the story rings true to me—some 70 percent of FBI men are Catholics, and this particular one is said to have been a Fordham graduate. And after all I can’t think of any men who have been a more profound embarrassment than the Berrigans to the Nixon Administration and to the FBI and to the Catholic Church—three entities of society which I, as an American and a Catholic, feel are in great need of being embarrassed still further.

When the recent indictment was handed down on Philip Berrigan and other Catholic peace activists on charges of conspiring to sabotage and kidnap, many persons speculated that it was precisely this embarrassment caused to the FBI by Daniel Berrigan’s stay underground that triggered the government to bring an indictment. But although Daniel Berrigan’s underground evasion was as bad a loss of face as the FBI has ever experienced, I think this view is blatantly flippant and incomplete. I tend to take a much more historical view of this indictment and I’d like to state at once its historical significance, because I think it has very grave implications for both political and religious freedom in this country.

I think this indictment is nothing more or less than the United States government’s effort to purge the Catholic Church of a radical, reformist movement which, for the first time in American history, has become a challenge and a menace to the secular establishment. Let’s not forget that the Catholic community in the United States, since its beginning, has always been a community remarkable for its docility, its conservatism, its often blind patriotism, its political predictability. These characteristics of the Catholic community were more than understandable in the context of early American society. Catholics had come into a predominantly Protestant culture whose origins were tinged with Calvinist intransigence. And for two centuries Catholics were trying to get accepted in an alien value system, striving to prove their Americanism and their patriotism by being super-American, super-patriots, ultra-flag waving, eager to produce as many Gold-Star mothers and All-Star football players as any Protestant group in the country.

Their ethos was most succinctly symbolized by Cardinal Spellman’s tours to Vietnam and his often repeated motto, “My country right or wrong,” and their classical prototype was the law enforcement officer. As Patrick Moynihan once put it, “It’s always the Harvard men who are being checked for security, and it’s the Fordham graduates who do the checking.”

This is the attitude of support that the American government has always received from the Church, has always counted upon the Church to give. And you need not stretch your imagination far to realize the shock and the discomfiture on the part of our government when all of a sudden, three years ago, it found that the most profound dissent movement to have rocked the United States since the slavery issue—I’m referring to the anti-Vietnam war movement—was being led, to a great extent, by Irish Catholic priests.

Well, what do you do when you are a group of intelligent and heavy-handed leaders faced with this force of dissent within the enormously powerful establishment that is the Catholic Church? You attempt to purge, the way Louis XIV purged the Church of Jansenists in the seventeenth century. Jansenism, although it was theologically dissimilar to contemporary Catholic radicalism, was akin to it politically, being the hotbed of anti-Royalist, antigovernment sentiment. The pattern of secular governments purging churches of their progressive leadership is not singular to us. It prevails most notably today in two other countries, Brazil and South Africa. Charming company.

A lot of people these days are asking why are Catholics taking such extreme stands, what has happened to that once sheepishly docile community? Well, I think that it is due in part to what is called the tradition of moral absolutism in our Church. If you’re brought up to believe that it’s a mortal sin to indulge in soul kissing and to eat meat on Friday, if you’re brought up to believe that you’ll burn in hell for these actions if you don’t confess them in that brown confessional booth, you’re apt to have very violent and passionate reactions to historical events.

Advertisement

It is perhaps because of this moral absolutism that Catholics are apt to take either the leadership of opposition or the position of greatest support in any polarized situation. In the 1940s in France, the Catholic priests played a major role of leadership in the anti-Nazi underground. In the 1930s in Germany, on the other hand, the Catholic Church was more abysmally absolute in its support of Hitler than any other religious body: not one German Catholic bishop ever spoke out. In the 1950s in this country, it was the Catholics, led by Joe McCarthy, who satanized Communism more militantly than any other group in the US, and we all bitterly remember how the Catholic hierarchy, led by Cardinal Spellman, played a leading role in supporting President Diem of South Vietnam and in formulating our present policy of counter-insurgency in Indochina.

And now in 1970 it is a group of Catholics who have demonized, satanized the Vietnam war more passionately and militantly than any other group in the country. A part of the Catholic Church has come of age, has lost its immigrant jitters, and has finally become a potentially radical, dissenting force in American society. Some of its members can finally feel free to prove their patriotism by protesting. I think that the concurrence of Pope John’s revolution and John Kennedy’s Presidency played a major role in liberalizing American Catholicism—John’s theological radicalism occurred simultaneously with the symbolic integration offered to Catholics by the first Catholic President.

I’d like to give you a brief biography of the two men who are the leaders of this extraordinary sociological phenomenon called American Catholic radicalism: the Berrigans. Daniel is forty-nine years old and a Jesuit; Philip is forty-seven and a member of the Society of St. Joseph, an order founded in the nineteenth century to work with the blacks. They are the two youngest of six sons. Their father was a second generation Irishman who worked as an electrical engineer in Minnesota and later in Syracuse, New York, where the Berrigans were brought up in conditions of some poverty.

Daniel joined the Jesuits at the age of seventeen and went on to get some MAs in theology and in philosophy; he taught at several Jesuit schools and colleges; he is the foremost poet in the Church today. He won the Lamont Poetry Prize in 1959 and just last year, in 1970, was nominated for the National Book Award.

Philip was an officer in World War II, saw active combat in France and in Germany, was a model soldier, won several decorations. When he came back he was graduated from Holy Cross College, where he wrote his senior thesis on “The Psychology of Nathaniel Hawthorne,” and continued on into the seminary and the priesthood.

I would guess that, until 1960 or so, the Berrigans were both fairly average Catholic priests—a bit more liberal than most because Daniel had been much influenced by the French worker-priest movement when he was stationed in France in the 1950s, but not so vastly different from all the other priests who used to sit in their rectories reminding you that you were in a state of mortal sin if you ate meat on a Friday or missed a Holy Day mass. Like many other Christians, the Berrigans were jolted out of this pleasant state of affairs by the series of crises that began to arise in the US in the 1960s.

By that time both Berrigans had become total pacifists because they believed it was the only ideology to hold in a nuclear age, and they had become militant on the subject of civil rights. In 1963 Philip Berrigan tried to become the first Catholic priest in the country to go on a freedom ride, but the Bishop of Alabama heard about his plan, had him paged in Atlanta where his plane had made a stop, and ordered him off the plane. Two years later, in 1965, both Berrigans lost their teaching jobs for the simple fact that they were the first Catholic priests to sign a petition against the Vietnam war. And a few months later Daniel was exiled to Latin America for four months for being one of the three cofounders of a very middle-ground organization called Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam. I hold the Catholic hierarchy as ultimately responsible for the Berrigans’ so-called radicalism. Such heavy-handed bungling is obviously going to make rebels out of the most obedient sons.

In October of 1967 I opened a New York Times and there on the front page was a photograph of Phil Berrigan, a very tall, very distinguished looking man who looks rather like a chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank, pouring blood on draft files in the Baltimore Draft Board in protest against the Vietnam war. It was an action which, for reasons that I will give you later, struck me as being an extraordinarily Biblical, traditional gesture, but for which he was sentenced to six years in jail. The following May, Philip Berrigan went back to another draft board, in the company of his brother Daniel and seven other Catholic priests and laymen, and destroyed 378 more draft files with homemade napalm, the recipe for which, let us note, they had found in a US army handbook. The recipe called for an emulsion of the purest available soap; and so the group used Ivory soap.

Advertisement

In April of 1970 the Supreme Court turned down the appeal of the Catonsville Nine, as the group was called, and several of the Nine went underground. Philip stayed under for two weeks and was apprehended in the vestry of a Catholic church in New York City. Daniel stayed underground for four months and was apprehended by the FBI on Block Island at the home of his friend William Stringfellow, a Protestant lawyer and lay theologian. His exile had not been devoid of humor. It is reported that the FBI had swarmed through numerous convents during Daniel’s underground exile, looking in closets, in bathrooms, under beds. And always keeping their impeccable Catholic manners, they would shout, “Are you there, Father Dan, are you there?” The Fordham graduates never forget to say Father, they never forget their Latin.

Finally, in August, six FBI men dressed as bird watchers converged on Stringfellow’s house. Father Dan was lying on the living-room couch reading St. John of the Cross. As the FBI men came into the living room, he went toward them to shake their hands and said, “You may wonder who I am. I am Daniel Berrigan.” They put the manacles around his wrists; he turned to his host William Stringfellow and said, “God bless.” And they took him away. There was an extraordinary photograph published throughout the country that week of Daniel being led to jail by the FBI—Daniel radiant, smiling in his most theatrical fashion, his face expressing pure joy and hope, and on either side of him the FBI men hunched up, dour, looking utterly terrified, as if about to go to the gallows.

Now the expression of Daniel Berrigan’s face that day was very important, because Daniel is a priest who has often preached that the essential attribute of the Christian is not so much faith or charity as hope. Hope is the essence of the Berrigans’ career. For the theory of nonviolent civil disobedience, whether preached by Christ, Tolstoy, Gandhi, A.J. Muste, or Martin Luther King, is based on the hope that the system is reformable without the need for physical violence toward people. This is where it differs from the Weathermen, cynics who have lost all hope.

To refine my definition, I’d say that civil disobedience is the last recourse before violence to change a situation which the silent majority has come to look upon as unchangeable. It is based on the idea that you break small laws—like defying lunch counter segregation laws, or bus segregation laws, or antistrike laws, or laws about draft files, or nineteenth-century laws forbidding you to shelter runaway slaves—to point out the existence of higher laws, like the brotherhood of man or the atrocity of war, which society seems to have forgotten about. Martin Luther King, after all, received a Nobel Peace Prize for a career of peace-making which was in part based on the defiance of precisely those kinds of small state laws.

And the reason I said to myself how historical, how traditional, when I opened The New York Times and saw Philip Berrigan pouring blood on draft files, the reason I was never put off or taken aback by the Berrigans’ mild attack on property, but rather astounded by their traditionalism, is that such actions have been performed since time immemorial by men with an apocalyptic turn of mind. By men who sense that there is not time to atone, to reform society by the habitual liberal channels—who sense that the world will come to an end if reform is not achieved very soon—and who indulge in highly dramatic, visible gestures, in morality plays of sorts, to alarm their fellow citizens.

To cite only a few examples of attacks on property that were models for the Berrigans: Jesus Christ over-turning the tables of the money changers in the Temple; Jeremiah smashing clay pots in the hall of the Temple—in protest, by the way, against his king’s war policy; Martin Luther burning a copy of Canon Law—the bad side of the Good News, as we call it; William Lloyd Garrison burning a copy of the American Constitution in the mid-nineteenth century in protest against the institution of slavery.

All these men were prophets, and some of them were also martyrs. Let’s not forget, however, that, as Robert McAfee Brown has noted, these prophets did not necessarily look upon themselves as models to be imitated, but as signs pointing to some truths we might otherwise forget. The Berrigans in particular serve as signs in our society by creating pictorial images that are painfully difficult to erase from our memory, that depict through metaphor the distorted moral priorities that have been erected in our society: such as the fact that we give medals to men who drop napalm on civilians in Southeast Asia, but give four, five, six years of prison to men who drop napalm on pieces of paper in the southeast United States.

This metaphor may seem simplistic but it is a poignant reminder of what has happened to the collective conscience of our nation and of the world. In 1937 world opinion was appalled when German planes bombed civilians in the Spanish village of Guernica. In 1970 we silently accept the fact that our planes are doing this every day in Vietnam in blatant violation of international law. We are outraged when paper—amounting to the legally defined value of some seventy dollars—is burned, and we are not outraged when women and children and harmless civilians are burned.

So when people complain that the action of the Berrigans was extreme, I think the Berrigans are justified in responding that extreme moral insensitivity on a national scale calls for some extreme of nonviolent action to challenge this moral insensitivity. As Daniel Berrigan wrote in his Preface to his book Voyage to Hanoi, “Our apologies, dear friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the parlor of the charnel house.”

Now in telling you what the Berrigans are about, what I think makes them tick, I’d also like to be critical. There is a terrible impatience in the apocalyptic turn of mind which Jeremiah and the Berrigans express. Most of humanity—you and I—are content to say, as St. Augustine said before his conversion: “Oh save me God, but not quite yet.” In the Berrigans’ view there is not time to say, “Oh save me God, but not quite yet.” In their view the times are irredeemably evil, and in their extreme pessimism they often use images which in my judgment are too extreme: such as their statement the day after the indictment, read right here outside of Danbury jail by William Kunstler, comparing the indictment to the Reichstag fire in Germany.

Such an image implies that we are already living in an era of Nazi-like repression. I rebel against this image. I think we may be heading toward a repression, but I think that language can create reality, that by saying the repression is already here we help to bring it on. I even feel that there’s a whole domain of massive nonviolent civil disobedience and other tactics of persuasion which we have failed to explore, which we must set about exploring, and which we have the liberty of engaging in under our present system.

Criticism two: There is undeniably a certain arrogance to the Berrigans’ sense of righteousness, an arrogance which is essential to the personality of the martyr. To think that your individual witness is going to help the state of the world presumes a certain vastness of ego. Why else would it be that martyrs are always praying for humility?

Criticism three—and it’s not so much a fault I see here as a possible anachronism: The Berrigans’ actions, and those of some 100 Catholics who have participated in some twenty different draft board raids to date, are grounded in a very ancient monastic mystique that is as old as the formulation of the rule of St. Benedict. In their view, a man’s witness in jail, like a monk’s years of passive prayer, can aid to purify society and to abate the violence of its rulers. This view, which implies that man can help to redeem society by searching for suffering in imitation of the suffering Christ, is perhaps too utopian for most of us to bear in the 1970s.

Although the Berrigans have helped to radicalize some parts of the population, especially Catholics, that were dormant and although they may have done more to revitalize the peace movement in the last three years than any other men, it is hard to predict whether their form of witness can lead to the kind of concrete organizing that is necessary for a new politics. The point of contact between a revolution of moral values—which is what the Berrigans teach—and a revolution of political values is difficult indeed to locate in America today.

Also, the extreme fundamentalism of the Berrigans’ thinking makes most of us uncomfortable. The Berrigans have a nostalgic ideal of the Church as it was in the first three centuries of its existence, before Constantine made it safe as a state religion, when to be a Christian meant to live under the constant threat of martyrdom, to live in poverty and persecution, paying no obeisance to secular power. The Berrigans are conservative on many points—they are adamant supporters of priestly celibacy, they are extremely rigorous in every area of ethics—and another area of conservatism in their thought is an irreconcilable division between the City of God and the City of man. In their view, man’s conscience belongs solely to God, and this allegiance must always supersede any allegiance to the state.

Curiously enough, it is in part the Berrigans’ fundamentalism which has gained them their chief champion in Congress—Representative William Anderson of Tennessee, who has gone to see the Berrigans here in Danbury Prison six times in the past five months. This is a Democrat from the Tennessee Bible belt, a former naval career officer who once commanded the atomic submarine Nautilus in the world’s first undersea crossing of the polar ice cap, a man who has turned from militant hawk to militant dove in the past year, and who has hailed the Berrigans as heroes in the nonviolent struggle for peace and accused J. Edgar Hoover of repressive tactics remindful of McCarthyism. Mr. Anderson told me recently that he sensed a similarity between the fundamentalism of his Baptist Bible belt constituents and the Berrigans’ moral fundamentalism. The chief difference being, he noted, that the Berrigans live the Gospel seven days a week, while his constituents live it at most one hour every Sunday.

Dan Berrigan’s letter to the Weathermen, published in a January issue of The Village Voice, is a document which can speak more eloquently for Dan’s intents than anything I can say. Why did Daniel Berrigan bother to communicate with the Weathermen? It is because he has always believed that one must meet with, and hold dialogue with, all members of our society, with hard hats and left-wing professors and Vietnamese and with apathetic Republican lawyers, with Black Panthers and with Ku Klux Klansmen. People like Klansmen—who after all are not so different from Weathermen in their tactics—are very much on Daniel’s mind. One of Daniel’s heroes is a very militant, radical civil rights minister in the deep South, Reverend Campbell, who often gets together with the local Klansmen in his corner of Alabama, and, as Daniel once described it to me, “Over a bottle of bourbon and a guitar they sit up and talk and sing late into the night, their differences being reconciled in what I as a Christian must call their common humanity.”

So here are excerpts from Daniel Berrigan’s message to the Weathermen, taped in the last weeks of his underground exile, which perhaps had something to do with the Weathermen’s decision to stop their program of violence, a decision publicly announced a few months ago.

I hope your lives are about something more than sabotage. I’m certain that they are. I hope the sabotage question is tactical and peripheral. I hope indeed that you are remaining uneasy about its meaning and usefulness and that you realize that the burning down of properties, whether Catonsville or in the case of Chase Manhattan Bank, or anywhere else, by no means guarantees a change of consciousness, the risk remaining always very great that sabotage will change people for the worse and harden them against future change.

How shall we speak to the people, to the people everywhere? We must never refuse, in spite of their refusal of us, to call them our brothers. I must say to you as simply as I know how, if the people are not the main issue, there is simply no main issue and you and I are fooling ourselves also, and the American fear and dread of change has only transferred itself to a new setting.

Our realization is that a movement has historic meaning only insofar as it puts its gains on the side dictated by human dignity and the protection of life, even of the lives most unworthy of such respect. A revolution is interesting insofar as it avoids like the plague the plague it promised to heal.

I personally doubt very much whether the author of this statement—or Philip Berrigan and the other five defendants in the Harrisburg case—can be guilty of the charges brought against them. I have no more proofs than any of you in this room. It is only on the basis of my faith in their nonviolence that I can state my hope and my faith in their innocence. I can say that in 1967, during all the months that Phil Berrigan was plotting his first foray on a draft board, he was often approached by people saying, “Let’s blow up this or that building at night when there’s nobody in it,” and Philip categorically refused to ever participate in such plans because, as he put it, how do you know there won’t be a workman cleaning up there at night, or a hobo or a drunk sleeping in the cellar? In other words he was prophesying that any tactic of sabotage could lead to a disaster similar to that in Wisconsin last fall when a young math instructor working at night in a lab was killed as a result of an idiotic left-wing bombing.

I have repeatedly heard Philip Berrigan and his friends refuse any sabotage tactics, and it is hard for me to believe that their ideology would have changed in the past year. The government’s evidence, as you may have read, is almost totally based on the testimony of a convict named Boyd Douglas, who not only has a long criminal record of fraud, impersonation of federal officers, interstate transportation of forged securities, physical assault on FBI agents, and violation of parole, but also has a record of psychopathic lying.

On the other hand, an awful lot of revolutionary fantasying goes on among even the most nonviolent members of a society as troubled as ours, and no doubt an awful lot of things may have been said in jest or fantasy which, when tapped, bugged, or repeated, could be made into government evidence. Sitting up with any of you late at night over a beer, I might say to you, “Hey, let’s spring the Berrigans out of jail tomorrow.” Or one of you might say to me, “Wouldn’t it be groovy to kidnap Kissinger and Jill St. John together.” I don’t think I could name one close friend of mine who has not indulged in this kind of fantasying in the past two years. But if we’re tapped, such a conversation can get us in trouble.

What is amazing is that some very conservative people are outraged by the implications of this indictment, by its incursions into citizens’ privacy, by its threat to freedom of speech. Paul Cowan of The Village Voice tells me that he talked with citizens of Harrisburg who told him: “Hell, we used to say ‘Let’s kill our teacher’ in school, didn’t we…we use a lot of words and expressions we don’t mean…what’s happening to our freedom if the government brings on these kinds of indictments?”

This reaction exemplifies, I think, a growing fear on the part of American conservatives as well as of liberals of the government’s growing incursion into our private lives and, more threatening than that, into our private thoughts, our private fantasies. And this is, in part, what this trial will be about if it ever comes to court. It is scheduled for October 1 or thereafter in Harrisburg. A few very keen news analysts think that the government’s evidence is so flimsy that the case will never be brought to trial, that the government will find some face-saving device whereby it can drop the charges. I fear that this may be an optimistic view—it is hard to imagine this Administration swallowing its terrible pride.

Finally, I’d like to say that if this indictment is indeed an attempt on the part of the government to purge the Catholic Church of its radical leadership, then this trial will be a very portentous testing of political and religious freedom in this country. For one of the most important roles that religion has played in human society has been to give man levels of transcendence beyond his political conscience, to give his conscience a foundation of liberty above and beyond the state. Christian religion has traditionally posited a most salubrious division between the City of God and the City of man and has taught, as St. Augustine put it, that man’s conscience ultimately belongs to the City of God.

Man will always remain a cultic, ritualistic animal. Perhaps at some later stage of evolution there will be a species of neo-man which may have lost this need for cult and ritual, but so far as we know, civilization from its earliest beginnings has always seemed to need cult and ritual of some kind. And the disintegration of such a transcendent force as the Judeo-Christian tradition, which has been the cornerstone of our Western society, can lead us dangerously close to what I call civic religion. Such a disintegration can rechannel man’s need for cult and ritual into a worship of the state—a phenomenon which we have witnessed painfully in Russia, China, Germany, and other totalitarian countries: It can lead to a cult of the state, a blind obedience to its dictates and trappings, an idealization of the flag and of other civic paraphernalia which result precisely in such occurrences as Mr. Nixon’s Sunday morning White House liturgies or the hard hat demonstrations last spring in New York City.

What those hard hats were saying to the peace protestors last spring was: “You don’t have the right to challenge or question the way a President leads a war.” What Daniel and Philip Berrigan have been saying in a much more traditional and orthodox way is, “We don’t have the right to render our conscience to anyone but God.” This is the tradition of the early Church, and this is the tradition of Christian saints and martyrs whom Catholics worship with such fervor while always forgetting that the martyr inevitably went to the stake because of having put his conscience above the dictates of the state.

I imagine that in some two or three hundred years, if the world still exists, the Vietnam war may well be written off in our schoolbooks as one of the most shameful events in American history. And if a church still exists, it is perfectly possible that at that time some element in the church will come along and try to canonize Daniel and Philip Berrigan for sacrificing their freedom to fight this most evil war. For this is precisely the way society treats its martyrs. It jails them and persecutes them and some hundreds of years later it canonizes them. Don’t forget that even the gentle St. Francis was persecuted as a heretic because, as the Church said, although involuntary poverty is the surest road to eternal felicity, voluntary poverty is a heretical concept. And it is said that the friends of St. Thomas Aquinas, upon his death, boiled his body in order to better peddle his mortal remains. Society is always very hungry for men of great religious conscience, and indulges in extraordinary kinds of culinary handiwork when faced with the problem of how to handle their memory.

In closing, I’d like to read part of a statement issued a few weeks ago by the defendants in the Harrisburg case during their arraignment. It was read by Sister Elizabeth McAlister, one of the six alleged conspirators. Sister McAlister is a nun of the Order of the Sacred Heart of Mary and a teacher of art history at Marymount College in Tarrytown, New York.

We are thirteen men and women who state with clear conscience that we are neither conspirators nor bombers nor kidnapers. In principle and in fact we have rejected all acts such as those of which we have been accused. We are a diverse group, united by a common goal: our opposition to the massive violence of our government in its war against Southeast Asia. It is because of this opposition that we have been branded a conspiracy.

Pure anguish for the victims of this brutal war has led all of us to nonviolent resistance, some of us to the destruction of draft records. But, unlike the accuser, the government of the United States, we have not advocated or engaged in violence against human beings. Unlike the government, we have never lied to our fellow citizens about our actions. Unlike the government, we have nothing to hide. We ask our fellow citizens to match our lives, our actions, against the actions of the president, his advisers, his chiefs of staff, and we pose the question: WHO HAS COMMITTED THE CRIMES OF VIOLENCE?

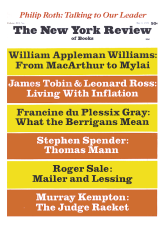

This Issue

May 6, 1971