The cruel choice between two evils, unemployment and inflation, has become the major economic issue of the day. Democrats and Republicans agree that both evils must be avoided and differ only on the means—with Democrats largely favoring the more drastic remedies. Congress has thrust upon the President authority for direct controls on wages and prices. The Administration has relied on traditional fiscal and monetary measures, including changes in taxes and spending and Federal Reserve control over the supply of money. First it tried to hold down prices by using tight money to restrain demand; now it is trying to create jobs by using budget deficits and easier money to expand demand. But the results, so far, are not encouraging. The traditional measures produced a recession and rising unemployment, but inflation hardly slowed down. Now both the recession and the inflation seem very stubborn.

Nevertheless, inflation and recession are usually alternative afflictions. One of the most dismal and best verified observations of modern economics is that there is ordinarily a trade-off between the rate of inflation and the rate of unemployment. Less of one means more of the other. Hence, full employment (which means an unemployment rate between 3 1/2 and 4 1/2 percent) can, on the average, be sustained only with 4 to 5 percent inflation. Price stability (another Pick-wickian term, meaning annual inflation of no more than 1 to 2 percent) is possible only with more than 5 percent unemployment.

The basic explanation for this trade-off (known to economists as the “Phillips curve”) is that, when business is booming and unemployment is low, labor and management can claim wages and profits which add up to more than 100 percent of the value of output they produce at current prices. Not everyone can be satisfied without a rise in prices. Inflation is a peaceful and anonymous resolution of these inconsistent and conflicting claims. When unemployment and excess productive capacity are high, claims for higher wages and profits are checked by actual or potential competition. But it would take a virtual depression to stabilize prices altogether.

One reason for the inflationary bias of our economy is that strong unions and corporations are insulated against the pressures of competition. But even in the competitive sectors of the economy there are powerful forces which push up prices during good times. The crucial factor is the universal reluctance to accept setbacks in money income. Wage rates for a given job can almost never be cut. Many firms would rather lose short-run profits than lower prices. The economy depends on changes in prices and wages as signals to move labor and other resources from sectors of declining demand to sectors of growing importance. But if prices and wages can never go down, there is only one direction in which they can move in response to changing economic conditions.

Although a slowdown of demand aggravates one disease, unemployment, while ameliorating the other, inflation, it does the first right away and the second with a lag. The first reaction of most businesses to disappointing sales is to cut output and employment, not to change their established price lists and wage scales. Unions do not give up hard-won wages as soon as actual or potential members become unemployed. Unemployed workers search for jobs at prevailing wages; they rarely volunteer to take a lower wage in order to get a job. Meanwhile the momentum of adjusting prices to past wage increases, and wages to past price increases, continues. The moderating effects of slack demand on prices and wages occur slowly and indirectly.

That is why 1970 was a year of both sharply rising unemployment and inflation. Today’s perverse combination of the worst of both worlds, 5 percent inflation and 6 percent unemployment, reflects the difficulty of transition from several years of rapid price increases. Continuing unemployment at current levels should eventually suffice to reduce inflation to 1 1/2 or 2 percent a year. But this would take two years or more.

Recessions aren’t good politics, as Vice President Nixon learned in 1958, candidate Nixon learned in 1960, and President Nixon learned in 1970. Through 1969 and 1970, the Administration patiently tried to manage a gradual and controlled slowdown by restricting the size of the budget deficit and the growth of the money supply. The effects on inflation were disappointing, but now the Administration has decided that the patient has had enough deflationary medicine even if his symptoms don’t yet exhibit a cure. The Administration aims to reduce unemployment to 4 1/2 percent by campaign time in 1972 by running a large deficit and holding down interest rates. Their hope is that we can meanwhile enjoy the best of the two worlds of which we had the worst in 1970. The deflationary medicine of 1970 hit employment and output, but its effects on prices were deferred until 1971-72. The expansionary medicine of 1971 will, it is argued, raise employment and output while price inflation is tapering off.

Advertisement

The scenario has some appeal but it is an unlikely one. First of all, the doses of expansionary policy seem inadequate. This Republican President, saying “I am a Keynesian,” has deliberately embraced deficit spending, sweetening the bitter pill for conservatives by promising to spend no more than the hypothetical revenues the tax system would produce at full employment. But in spite of all the rhetoric about the “full employment budget,” fiscal policy will be no more expansionary in 1971-72 than in 1970-71. Both federal expenditures and revenues are, according to the budget proposals, to rise at the normal rate of growth of the economy; in both fiscal years a “balanced full employment budget” is projected.

But that will not be enough to achieve full employment. For an easy money policy the President is dependent on Arthur Burns, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, who is in no mood to validate the Administration’s forecasts and targets. Burns wants to see more evidence that inflation is abating, and he wants more direct action to control specific wages and prices than the President and George Shultz, his economic Kissinger, are willing to take.

A more likely prospect is several years of high unemployment, 5 to 6 percent, and gradually ebbing inflation. At best, we may return to the familiar situation of the late Fifties, with unemployment meandering around 5 percent because the makers of monetary and fiscal policy are afraid of the inflationary consequences of measures to restore full employment.

Is that the world we want? Five and a half percent unemployment for the nation translates into between 11 and 12 percent for the young and for blacks (and perhaps twice that for the black young). It amounts to an annual sacrifice of roughly $55 billion in unproduced output compared with the full employment level. In short, victory in the war on inflation has an enormous cost. Perhaps, instead, we should explore the path of peaceful coexistence with inflation—making it more bearable, and learning to live with it.

The first step is understanding just what harm inflation causes. Here, as elsewhere, conventional journalistic and political wisdom is a poor guide. The major charge against inflation is that it redistributes income unfairly. Supposedly, wages lag behind climbing prices and corporate profits. Old people on fixed incomes, savers, welfare recipients, and government employees are all said to suffer a severe loss of purchasing power. Inflation, the phrase goes, is “the cruelest tax of all.”

The facts tell a different story. The major gainers from inflation are workers who would have been unemployed or underemployed had prices been kept lower. This group, of course, is heavily made up of the poor and the young. A 1965 study by Metcalf and Mooney for the OEO estimated that a shift from 5.4 percent to a 3.5 percent national unemployment rate would result in an increase in full-time employment of 1,042,000 for the poor.* The net result would be to move 1,811,000 people above the “poverty line,” as it is defined by the government. Apart from its effect on unemployment, inflation neither systematically helps nor hurts the working man. There is no evidence to suggest that labor’s share in the national income—the percentage of total income paid to workers—deteriorates during periods of inflation.

Social security and welfare payments also catch up with inflation after a brief period, although they may fall short in the initial stages. Some people who save are hurt, but primarily because government regulations place a low ceiling on the rates banks and savings and loan associations can pay to small depositors. Without the ceiling, deposit rates would rise along with general interest rates. The only consistent losers from inflation are those whose incomes are fixed by preexisting contracts, especially old people living on private pensions and holders of long-term bonds. But only the former group embraces the poor—bonds are an encumbrance of the well-to-do. Over-all, our only major concern about the effect of inflation on the distribution of income should be for pensioners, and it would be much less painful to subsidize pensions than to suppress inflation.

A more fundamental problem is raised by Milton Friedman and others, who deny that we can reap the gains of high employment by choosing to live with more inflation. They argue that there is no long-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment. The Phillips curve, in their view, expresses only short-run alternatives. In the long run, there is only a single, “natural” rate of unemployment for a country’s economy. If we try to reduce unemployment beyond this point we may have some temporary success, but the resulting price increases will prod unions and other workers to raise their wage demands, while inducing employers to grant them. Once again, the sum of wage and profit claims will exceed the value of output available to satisfy them. An even higher rate of inflation will be necessary to resolve this conflict.

Advertisement

Moreover, Friedman argues, this new round of inflation will also, in turn, be reflected in a new round of wage demands. As a result, the Phillips curve trade-off will become increasingly worse. Where initially we might have been able to choose 3 percent inflation with 4 percent unemployment, we might soon have to accept 6 percent inflation for the same rate of joblessness. Over time, in this view, the economy cannot choose its rate of unemployment, but can merely decide how much inflation it wishes to endure in a futile attempt to alter that rate.

Friedman’s argument rests on an appealing but unverified assumption: that you can’t fool all of the people all of the time. If labor and business are making inconsistent demands, then in Friedman’s view a mere renumbering of prices and wages through inflation will not resolve the conflict. But, in fact, the evidence suggests that even sophisticated people are far more sensitive to direct losses in money incomes than to declines in their purchasing power through higher prices. Wage and salary reductions are almost unknown in industrial countries, even though it is not uncommon for employees to suffer temporary losses in purchasing power. So long as wages and prices are set in dollars, and money retains its age-old power to deceive, inflation can be used to resolve economic conflict.

Statistical studies have yet to verify a one-for-one feedback of price rises on to subsequent wage demands; current estimates for the US are that from 35 percent to 70 percent of price increases are ultimately translated into subsequent wage increases. This does not mean that labor is losing out—prices do not for long move more than in proportion to wage costs—but simply that there is a damper on the inflationary process. Perhaps ultimately inflation can be no more deceptive than the change of the monetary unit from, for example, old francs to new francs with two fewer zeros, and have no greater effect on real behavior. Perhaps “money illusion” is a transient phenomenon. But the period of adjustment is measured in decades rather than years. If so, the Phillips trade-off is real enough for the practitioners of economic policy.

Everyone can agree to one implication of the lagged feedback of price inflation to future wages and prices: the alternatives we face are more unfavorable than first appears. Thus, the full cost in inflation of the high employment policy as of 1966 and 1968 will be far more substantial than what was immediately felt. But observe that anticipated inflation is harmless inflation. The same foresight that gives it momentum means that few are caught unaware by the “cruelest tax.” And if the sting is gone from inflation, there is nothing wrong with having more of it.

Removing the sting has not been seriously considered as an alternative to anti-inflationary policy. Yet it is not hard to devise measures that would make inflation less painful and inequitable. People living on low, fixed private pensions could be granted federal cost-of-living supplements, just as those who suffer unemployment as a result of government policy are given public assistance. The discriminatory ceiling on bank and savings and loan deposit rates could be removed. Cost-of-living escalators could be built into welfare and social security payments, and both small savers and pension funds could be offered an inflation-proof bond with adjustable interest payments. There is no reason why a nation with a financial structure as elaborate and costly as ours cannot find a way to allow ordinary people to protect themselves against inflation.

These measures may seem to be palliatives, with the drawback of delaying a more fundamental solution. Inflation can abate only when one or another group in society is forced to settle for less real income than it had previously been striving to obtain. If old people and welfare recipients are protected, some other group—more affluent and perhaps politically more powerful—must make the sacrifice. Cost-of-living protection may make the economy somewhat more prone to inflation, while distributing the burden of inflation far more fairly. Still the bargain seems attractive, since any remaining harm from inflation must be weighed against the gains in employment and output. So long as a more fundamental solution means chronic high unemployment, we are not in a position to be scornful of palliatives.

One reservation is necessary in this case for cushioned inflation. Concern for the balance of payments limits our freedom to inflate at will; this is no doubt a major reason for Arthur Burns’s caution. So long as the exchange rate between the dollar and other currencies is kept fixed, inflation in the US that is faster than that in the rest of the industrial world will damage our exports, increase our imports, and push more dollars into the hands of nervous foreign governments and central bankers. Like General de Gaulle a few years ago, they may ask for gold, or at least make us uncomfortable by threatening to do so.

Twelve years of living under this gun have at last made most observers realize that it is not really loaded. There is now widespread understanding in political and financial capitals, as well as among academic economists, that exchange rates among currencies cannot be permanently fixed, and that the present dollar standard places the onus of changing them on other countries, not on the US. European central banks can always avoid unwanted accumulation of dollars by making their currencies more expensive. If instead they insist on piling up dollars and then cashing them in for gold, they can no doubt force the US to cut the link between the dollar and gold. But this would be no calamity for the US; indeed, it would make clear our freedom to pursue economic policies that meet our domestic objectives. For that reason, our friends abroad are not likely to precipitate such a showdown. It is more likely that the international monetary system will continue to evolve toward more flexible arrangements.

So let us aim at the 4 percent unemployment rate, which would in effect mean full employment, and accept the 4 percent inflation that comes with it. But it is also vital for us to take measures that will over the long pull diminish the inflationary bias of the economy.

Improving labor mobility is the least controversial prescription. Anything that helps to match unemployed workers with unfilled jobs—computerized placement, retraining, moving allowances—helps to reduce unemployment without accelerating inflation. Some programs exist already, but much more can be done.

Reduction of monopoly power is another promising approach. One reason for the Phillips dilemma is that strategically placed unions and industries can claim more in income than they produce, with little discipline from competition. For example, when they face high and rising demand, they can be quick to raise wages and prices. When they face falling demand, unemployment, and excess capacity, their wages and prices do not respond. An effective solution requires curbing these mutually inconsistent concentrations of power.

The necessary reforms include freer access to the skilled trades and the unions in those trades; stricter anti-trust action in industries dominated by a few firms; and greater acceptance of foreign competition as a way of policing domestic markets. This last item is of special importance today as import quotas and other trade barriers gain political favor. Existing quota systems already contribute generously to high prices—a prime example is the oil import limitation, which makes consumers pay $4 billion a year above world prices. New restrictions can only make matters worse.

But structural reforms to increase mobility and competition will happen slowly if at all. In the meantime, if we want to improve the Phillips trade-off we must consider a more direct approach. The alternatives are guide-posts—what Paul Samuelson has called “talking the Phillips curve down”—and controls.

The Kennedy and Johnson administrations attempted to exert government influence on major wage and price decisions through the promulgation of “guideposts for non-inflationary wage and price behavior.” Wages, according to the guideposts, should rise by no more than the annual increase in average labor productivity in the economy as a whole. Prices should fall in industries with above average productivity gains, and rise in laggard sectors, in order to keep the over-all price index steady.

Guideposts under favorable circumstances can possibly somewhat reduce the level of inflation to be expected from any given rate of unemployment. During the early 1960s they seemed to have this effect. Why they worked is unclear. The Kennedy steel price confrontation may have made big business wary of government retaliation if prices rose too sharply. Alternatively, guideposts might have helped to deflate price and wage expectations. Since inflation often proceeds through futile attempts to stay ahead of the race, one way of curbing today’s inflation is to convince everyone that tomorrow’s won’t be so bad.

To have this result, guideposts must be within shooting distance of the wages and prices that business and labor are already counting on. Thus, after a year of 5 percent inflation, it is hopeless to ask workers to settle for a 3.2 percent annual wage increase (the Kennedy administration’s target figure). Some adjustment must be made for the previous loss of purchasing power. Unrealistic limits helped to torpedo the guideposts during the first years of the current inflation.

President Nixon began his administration by renouncing the use of guideposts and other “jawboning” techniques. Big business followed suit with a series of price increases which seem to have been postponed until right after the Inauguration. By one estimate, wholesale price inflation ran 1/2 percent higher in 1969 than economic conditions might explain. Overall, the Administration’s shift from jawbone to wishbone did not bring better luck, and its recent bouts with the steel corporations and construction unions indicate a slight change of strategy. But the main line of Administration thinking is still against guideposts and controls.

Out of frustration with the current regime of high unemployment and high inflation, Congress has prodded the President to adopt direct wage and price controls. Controls, if imposed, would undoubtedly resemble the overall freeze of prices and wages adopted during the Korean war more than the detailed OPA price schedules in effect in World War II. A case can be made that the Korean controls were useful in bringing a rapid inflation to a fairly smooth halt. Controls were imposed just as the rapid inflation caused by the beginning of the war was running out of steam; thus the ceilings were superfluous in many areas of the economy, while elsewhere their mere existence helped to break inflationary expectations. The prices of raw materials, in particular, were sensitive to expectations of future price changes and had been crucial contributors to the inflationary spiral. Before controls were adopted, speculation had pushed wholesale prices ahead by 15 percent in six months. The price freeze helped to reverse this trend and prevent it from spreading to the rest of the economy.

Are compulsory controls the answer? Permanent controls are certainly no solution to the chronic problem. Permanent controls are bound to be detailed controls, and any attempt to bureaucratize the immense variety of prices and wages throughout America would be a nightmare. A temporary freeze is another matter. As the Korean experience indicates, a freeze can be a useful psychological shock, puncturing abnormal inflationary expectations and hastening the restoration of normal price trends. Like the Korean war, though for different reasons, the Vietnam war left in its wake an inflation out of line with current and prospective rates of unemployment. A freeze could perhaps have restored the normal Phillips relationship sooner and permitted an earlier and more vigorous expansion of aggregate demand. The time for such a policy is probably past, since the exaggerated inflationary expectations of 1970 now seem to be abating.

The management of the economy has been particularly inept since 1965. But even in the best of circumstances, the unpleasant fact remains that full employment implies creeping inflation. We had better recognize that the costs of such inflation are much less than the costs of avoiding it. A sensible policy would pursue full employment and act to cushion the inflation that results. Automatic pension and welfare adjustments and an end to discrimination against small savers could virtually eliminate any hardship from this course of action. It is time for us to recognize that jobs and output, not prices, are the real measure of economic performance. The purchasing power of wages and incomes, not the purchasing power of dollar bills, is the true gauge of economic welfare. We can live with inflation, but we cannot afford a stagnant economy. Nobody likes to pay twenty cents for a cup of coffee, but almost everyone is better off than when coffee cost a nickel.

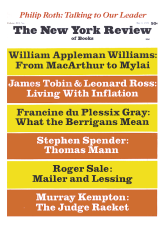

This Issue

May 6, 1971

-

*

C. E. Metcalf and J. D. Mooney, “Aggregate Demand Model,” unpublished working paper for the OEO, 1965, cited in R. G. Hollister and J. L. Palmer, “The Impact of Inflation on the Poor,” Institute for Research on Poverty discussion paper, University of Wisconsin, 1969.

↩