In early July, 1970, I was asked by a group of young doctors and divinity students to visit Lewisburg Federal Prison, where Father Philip Berrigan and David Eberhardt were being held in solitary confinement after they had undertaken a fast to protest a series of alleged harassments and restrictions which many in the Catholic peace movement felt were designed to pressure Daniel Berrigan, then still underground, to turn himself in (NYR, November 5, 1970).

Upon his return from Lewisburg, I met with Daniel Berrigan to tell him about his brother’s medical condition; and soon thereafter, two weeks before Daniel Berrigan’s capture on Block Island, we began a series of recorded conversations which lasted for seven days. What follows is the first of several excerpts from these conversations that will appear in The New York Review; the complete text will be published in September as The Geography of Faith.

R.C.

COLES: You keep mentioning what I suppose we could call the “outside” or “objective” problems—which plague all continents and nations. How about violence and hate and exploitation in what is loosely called the movement? How about the brutishness one can presumably find in the underground, which is presumably made up of people who are escaping from what they conceive to be the violence of the society but which clearly has in it people who do not hesitate to use violence and endanger innocent lives?

BERRIGAN: It seems to me that there are rhythms in everyone’s life which require the kind of passive suffering that John of the Cross speaks about. When the Weatherman phenomenon was growing I had a choice of going forward with that development, and somehow making an adjustment and being at the side of the people who were preparing for violence and becoming less and less concerned with nonviolence. Or I had the option of standing aside, and I chose to do so because I couldn’t accept that kind of approach, that violence. And I felt it important to tell those students going in the Weatherman direction what I felt, even if it meant they would no longer want to talk with me—which would be sad. I hope that one day sanity and compassion and community will assert themselves over all of us, the violence-prone in the movement and the violence-prone who run countries and order bombers to drop bombs and men to shoot at men.

C: Do you think that day is near at hand?

B: I am not so pessimistic about some of the students as I am about some of our politicians. I know some young people who have been Weathermen. They have gone through great personal anguish and tried to change this society, without much success, which they cannot forget. When they were picked up by the police they were not underground, but they were picked up in communes which they were forming for students and for working people and they were doing what the Panthers had been doing in New York City. They were with the people. They were dealing with students, especially high-school students, and with the poor. Now they are in jail, and with very high sentences for what they did.

C: What did they do?

B: They were involved in trashing in Chicago, both at the Convention and later when there were those other explosions going on, too; and, as I said, that’s all over with now because I believe they have undergone a change of attitude.

C: Then you feel that the law should not punish them for what they have done?

B: Let me speak personally. At this point the law is after me. I have never been able to look upon myself as a criminal and I would feel that in a society in which sanity is publicly available I could go on with the kind of work which I have always done throughout my life. I never tried to hurt a person. I tried to do something symbolic with pieces of paper. We tend to overlook the crimes of our political and business leaders. We don’t send to jail Presidents and their advisers and certain congressmen and senators who talk like bloodthirsty mass murderers. We concentrate obsessively and violently on people who are trying to say things very differently and operate in different ways.

C: How would you apply your thinking to those on the political right who would like the same kind of immunity from prosecution and the same kind of right to stay out of jail in their underground?

B: Well, that subject came out very acutely at our trial; the judge and the prosecution essentially asked me the same question you just did. How would we feel about people invading our offices and burning our files? And our answer was a very simple thing: if that was done, the people who did it should also present their case before the public and before the judiciary and before the legal system and work it through and submit themselves to what we went through.

Advertisement

C: Well, how about one of the chiefs of the Klan who was arrested a while back and went through the process you describe—and as a result went to jail?

B: Yes, I think he is now in jail.

C: Would you argue that he perhaps should have taken to the underground?

B: Well, it seems to me what we have got to discover is whether nonviolence is an effective force for human change. The Klansmen, as I understand it, have been rather violent over the years; so their methods are not ours.

C: Are their methods any different from the Weathermen’s methods?

B: Well, I look upon the Weathermen as a very different phenomenon because I have seen in them very different resources and purposes. I believe that their violent rhythm was induced by the violence of the society itself—and only after they struggled for a long time to be nonviolent. I don’t think we can expect young people, passionate young people, to be indefinitely nonviolent when every pressure put on them is one of violence—which I think describes the insanity of our society. And I can excuse the violence of those people as a temporary thing. I don’t see a hardened, long-term ideological violence operating, as in the case of the Klansmen.

C: You don’t see that kind of purposeful and unremitting violence in the students?

B: Well, I am hopeful that the violence I do see in them will not take over and dominate them. I am going to continue to work—so that it doesn’t happen.

C: This issue is a very important point, and I find it extremely difficult to deal with because—in my opinion and I’ll say it—you’re getting close to a position that Herbert Marcuse and others take: you feel that you have the right to decide what to “understand” and by implication be tolerant of, even approve, and what to condemn strongly or call “dangerous” at a given historical moment. You feel you have the right to judge what is a long-term ideological trend, and what isn’t, and you also are judging one form of violence as temporary and perhaps cathartic and useful or certainly understandable, with the passions not necessarily being condoned, whereas another form of violence you rule out as automatically ideological. It isn’t too long a step from that to a kind of elitism, if you’ll forgive the expression—to an elitism that Marcuse exemplifies, in which he condones a self-elected group who have power and force behind them, who rule and outlaw others in the name of, presumably, the “better world” that they advocate. There is something there that I find very arrogant and self-righteous and dangerous.

B: O.K. Well, let’s agree to differ on that, maybe from the point of view of a certain risk that I am willing to take in regard to those young people—a risk that I would be much less willing to take in regard to something as long-term and determined and as formidable as the Klan. But I am willing to say that there is always danger in taking these risks, and that the only way in which I can keep free of that danger, reasonably free of it, is by saying in public and to myself that the Weatherman ideology (for instance) is going to meet up with people who are going to be very harshly and severely critical of it, as I have been and will be; in fact, at the point in which their rhetoric expresses disregard of human life and human dignity, I stand aside and I say no, as I will say no to the war machine. But I discern changes in our radical youth, including the Weathermen. And again, I have hope for them, hope they will not be wedded to violence.

C: You feel they are no longer what they were?

B: Well, at least now there are divisions among them that are very significant, and with respect to the general agreement that they have to remain underground and do underground work, there are very different reasons among them for doing that. Many of them have gone underground to work with the poor, rather than to use dynamite.

C: They are not all of a piece?

B: Absolutely not.

C: They vary in many ways?

B: We simply cannot talk about just one stereotype of the Weathermen, or one kind of rejection of our society. I am going to try to work with them.

Advertisement

C: Work at communicating with them?

B: Right, and disagree with them thoroughly at times; because there is an absolutely crucial distinction between the burning down of property and the destroying of human lives.

C: You feel the courts and all of us as citizens should understand the distinction between the two?

B: Yes, and not only understand the distinction but embody it and gear their actions to that kind of distinction. This was acutely in my mind when I went to Catonsville. I wanted to emphasize how wantonly lives have been squandered in Asia—with no one punished for doing so; whereas we get stiff sentences for trying to highlight the tragedy by burning up government paper.

C: You mentioned a little while back that you especially have hope for our young who are university-educated and who have their ideals if not their actions grounded in certain values that you share. I strongly disagree—in the sense that I have not found that people in universities (or for that matter many others who in this century have proclaimed the brotherhood of man) are any more immune to arrogance and meanness and viciousness and snobbery than others of us are. Many of the people I work with (they are now called “middle Americans”) are young people—and you don’t talk about them, maybe don’t know them. You mention young people often, but large numbers of young people are not going to universities, are not necessarily involved in politics, and may not be inspiring to people like you or me because they lack a political consciousness. But some of these young people may not be as murderous as some of the young people you’re talking about.

I think we’ve got to face squarely murderousness everywhere, even within our own ranks or among our colleagues or whatever. I can’t be any more hopeful about some of the young Weathermen or some of the other young radicals than I am about the young, nonideological workers in this country, or for that matter the Southern whites I’ve worked with in the past. After all, one can say that in the past fifteen or twenty years Southern white people have gone through some very significant changes, and have responded in ways that neither they nor to my knowledge many of the leaders in the civil rights movement believed possible at the time (say 1960 or 1962 or 1963) the civil rights struggle was being waged in that region. In 1962, I heard very tough members of SNCC and CORE say that any school desegregation in Mississippi was ten or fifteen years off!

I don’t quite know how to put this clearly, but I get a feeling that sometimes we reserve for ourselves the right to ignore the most flagrant kinds of ideological rigidity, intellectual arrogance or meanness, and internecine warfare within our own cadres, then turn on others and criticize them for demonstrating similar qualities of mind and spirit. We deny others the kind of understanding and charity and compassion we ask for ourselves.

B: Well, I have no real difficulty with the kind of reservations you are expressing. It seems to me that practically everything we do or try to do produces a very tentative attitude among intellectual people—who worry and should worry about a lot of dangers and sins we are all prey to. I must say I am operating in our discussion out of a two-edged conviction that the university is the place where, ideally and even sometimes in fact, humanity and human values are at least respected. I have no illusions about what happens in classrooms and what happens among academics—with their political jockeying for power and place. It all goes together—the valuable things in our universities and the ugliness, the essential ugliness of so much of that scene. But on the other hand I did see in three years, three very full years at Cornell, which was my last kind of experience—I did see great things happening to certain members of that community, and I was one of the most savage critics of 90 percent of what was going on among students, faculty, and mostly the administration. So, despite my reservations, I do retain a conviction that the university is going to be a crucial proving ground for man’s survival.

On the other hand I feel that the university scene is progressively condemning itself to death, and that the university as we have known it, just as the church as we have known it, is not going to survive. Even so, there is much that is important going on in both of those scenes—in our universities and our churches: people are pushing and shoving one another, and looking at themselves in new and honest ways. One finds so much surface there and so much rage, so much selfishness, and, on the other hand, so much grandeur, so much real self-criticism. It seems to me that the university should be such a scene—because just as there are so many contradictions in American society, so one finds those contradictions on our campuses. There is no doubt, however, that having gone through the Fifties, gone through the McCarthy era, we are now seeing analogous dangers from the left.

Well, you sense my ambivalence here. I was attracted to the university scene because I had a growing feeling that there I could learn in a kind of laboratory, a kind of hothouse laboratory of human expression and human passion—I could learn what man might become or what he might refuse to become or how he might condemn himself to become nothing. And when I chose to live in a university setting I guess I lost touch, let’s say, with working-class people and their struggles, or the ghettos and their struggles, or the South and its struggle. But living in a university seemed very like the church scene so familiar to me—in the sense that a long tradition was in the throes of something very hard to define, something having to do with the struggle of life against death.

But any scene of mixed life and death is extremely instructive for the future, and is bound to be confusing and ambiguous and troublesome. I feel now as though I am being too abstract with you. Maybe I do tend to condone things, and need to be reminded of that; or maybe I do gloss over things because people I am instinctively or traditionally sympathetic to (rather than Klansmen) are doing them. The scene I’m in, like all scenes, I guess, is very skillful in concealing its own inherent ugliness, glossing over it with various self-justifications.

C: The radical scene?

B: Obviously, yes. What I am pleading for, what I continue to plead for, is that we see the reasons some of our radical youth have turned in the directions they recently have turned. To be very concrete, I have felt that the Weatherman phenomenon need never have occurred, and according to right reason should not have occurred, and in times which were less assailed by corrupt authority and corrupt power need not have occurred. The first instincts and the first tactics of these young people, at least in my experience of these young people, were not violent. They became violent. I ask why.

C: So you say our society has driven them to this?

B: That is the simplest way of putting it, and, you know, we could be very concrete about this, and I could say that on the scene I knew, if there had been a different chronicle of events in the late 1960s, the young people would not be so bitter and disillusioned.

C: You could say that about the Klan—that our society has driven them to do what they do.

B: Well then, all right, all right, and there again, let the Klan come forward and speak out its program, and let the Klan examine its own beginnings.

C: In the South one can hear the Klan doing precisely that all the time! Anyway, I don’t mean just the Klan. I am trying to say that it is dangerous to say that people do only what society drives them to do. I am concerned with the issue of the individual’s moral responsibility. I don’t believe we are social automatons, at the mercy, always; of what politicians and other leaders decree.

Then there is another question I’d like to ask you. How can a complicated society like American society, a large nation of many groups—how can it exist and stay reasonably intact and allow itself to be systematically undermined by any group that uses dynamite, that uses sustained violence and justifies that use? Now if you then say that every time this occurs one has to understand endlessly how the people in question got that way, came to do what they did—then where are we? Where are you as a theologian and I as a psychiatrist—where are we with these individuals; that is, where are we as citizens of a nation that has laws and a constitution which sanctions those laws?

It is ironic that here the two of us are talking about people who presumably have a sense of moral responsibility and presumably feel themselves to have sensitive consciences. How can you and I, as people concerned with individuals, say that a given man or woman is only what society has made him or her to be? I don’t quite agree with you. I think that the lives and deeds of some of the people we are talking about are not necessarily to be explained by what has been happening in America in the last three or four years. There is in some of their behavior, I think, a kind of petulance and meanness that I don’t think I am ready to explain as only a function of the American political system. I think at some point we have to talk about individuals, we have to judge individuals—even as we ourselves have to be seen and maybe condemned for the individual choices we have made, or not made.

B: Yes, but at the same time I feel that our discussion is, at least so far, lopsided in its concentration upon the violence of a few who are out of power. We have not emphasized the violence of those who are in power. It seems to me that we, that you, are looking at the society as a kind of Platonic entity which is self-justifying on principle and is functioning on behalf of individuals and for human life with a kind of structured compassion and justice and decency—and it is exactly those suppositions I take issue with. That is to say, the society itself is under judgment; I refer to its values, its deeds, its relationship to the international community, especially the Third World. I feel that the best way to understand the violence and alienation of our young radicals is to look at America’s violence and America’s alienation from the struggle of hundreds of millions of people for freedom from Western imperial rule.

I was just saying that our society has to be seen for the violent one it has been historically—and still is. My brother is in prison and I am a hunted felon—but men who plot war and shout racist obscenities are high officials of the federal government or governors or United States senators. The government pursues us just as it pursues its war—which means the government has certain all too consistent values some of us don’t want to examine closely, lest we be made nervous or ashamed. To get to the real point: the supposition that society is a competent judge of its own members and of their activities ought to be subjected to the closest scrutiny and suspicion. It is up to good men to do so constantly. I simply can’t say to you tonight that I believe that the government as it is now constituted is fit to judge either me or the Klan or the Weathermen.

C: But who is to decide whether the government is fit to make such judgments? Who decides whether the government is hopelessly corrupt and evil or simply a government, hence like all governments flawed somewhat? America is a nation, now 200 years old; and it is this nation whose history in some ways haunts us. America has institutions and these institutions are givens, in the sense that we were born under a certain kind of government and in a certain nation, and we grew up to find out that this is our country. We can’t reverse past history—only try to make a different kind of history for our children to possess as their heritage. You are saying that our institutions are not fit institutions and therefore have no right to exercise their authority as institutions and determine, for instance, how to deal with violence, whether it be from the Klan or from the Weathermen. But if those institutions don’t have such authority, which institutions, which people do?

B: We do.

C: Who is we?

B: Well, we are that small and assailed and powerless group of people who are nonviolent in principle and who are willing to suffer for our beliefs in the hope of creating something very different for those who will follow us. It is we who feel compelled to ask, along with, let’s say, Bonhoeffer or Socrates or Jesus, how man is to live as a human being and how his communities are to form and to exist and to proliferate as instruments of human change and of human justice; and it is we who struggle to do more than pose the questions—but rather, live as though the questions were all-important, even though they cannot be immediately answered.

My purpose in life is not to set up an alternative to the United States government. We in the underground are trying to do something else. We want to say no to everything that is antihuman, and to suggest new ways for human beings to get on with each other. I believe from my own experience and from what I have seen happen to others, that a new kind of life, a new way for people to live with one another, is quite possible—though I can’t be as clear about the details of that life as you might wish, except to tell you at least this: I am trying to live now (to pay the price now of living) in a way that points to the future and indicates the directions I believe we must all take; and I can only hope that the future I speak of and work for and pray for will come about.

C: You are living out your present life in a way that you trust will make a difference to others yet unborn?

B: Yes, by living today as though the kind of tomorrow one prays for and dreams about is not completely unobtainable.

C: I’d like to get to a point that we almost reached just a while ago. I think you were saying or implying that people like me spend a lot of time discussing the violence of the radical left, or for that matter posing it as an issue comparable to the issue of the violence of the radical right, and at the same time—because of the kind of lives we live, because of the comforts and privileges we enjoy—do not dare to look at the institutionalized violence that is sometimes masked and veiled but is part of everyday life. Is that what you were saying or implying?

B: Well, the analogy I think that I am drawing upon is again the only one I know—the Biblical experience of a man, Jesus. How does one really raise ethical and political questions and explore those questions in a real way—as contrasted to an academic or an intellectual way? Can someone question gross and blatant injustice from a life situation that is tied in dozens of ways, often subtle ways, to that injustice? That is to say, it wouldn’t have meant much to many of us if Jesus had raised questions of conscience and of God and man from the position of a Pharisee, from the dead center of his society.

I can only mention a conviction, one I have tried to follow out, sometimes clumsily and incompletely—a conviction that one’s position in relation to a given society is terribly important, and bears constant watching. I find across the board that the position of clerics with regard to their ability and freedom to communicate (to be honest with themselves and others) resembles the position of lawyers or psychiatrists, or those in any other profession.

We are finding that many people, young and older, find it unacceptable that a priest or minister make one religious pronouncement after another, and himself be immune from suffering or risk based on ethically inspired action; or that a lawyer talk endlessly about the law and its meaning and value and purpose and himself do nothing to experience legal jeopardy—in order to show the high crimes that poor and vulnerable people (from soldiers abroad to farm workers at home) experience at the hands of—yes!—our lawmakers. My point is a very simple one: that we as active and concerned individuals are historically valid and useful for the future only in proportion as our lives are tasting some of the powerlessness which is the alternative to the wrong use of power today; and that’s where I am.

C: At the edge.

B: At the edge. I suspect that in the traditional sense it is not necessarily a religious position, because all of these questions are very rapidly secularized. To put it very bluntly, the Jesuits of the sixteenth or seventeenth century lived underground in England to vindicate the unity of the Church. They were willing to do so rather than sit back and take no action to signify their sense of horror at the breakaway of England, an event which was to them a life and death question. And Jesuits have died to vindicate the truth of the Eucharist in other European countries. These were, of course, religious questions posed in a religious context.

Protestants can speak in the same way about their martyrs. The difference now is, as a man like Bonhoeffer illustrated for us, that the questions are being posed across the board in a way that says: Shall man survive? Shall he weaken? Are you willing to live and to die in order that men might gain and win freedom—and not literally die in a holocaust or die the slow death that is the destiny of millions of the earth’s poor, but die as a smug burgher in order to live for justice’s sake? I can’t conceive of myself as a Jesuit priest dying on behalf of the Eucharist, dying to vindicate the truth of the Eucharist, except in a very new way—except as the Eucharist would imply the fact that man is of value and that one does not kill and that one does not degrade and violate human life and that one is not a racist. Today, in other words, the important questions have an extraordinarily secularized kind of context. So I find myself at the side of the prophets or the martyrs, in however absurd and inferior a way, and I find no break with their tradition in what I am trying to stand for.

C: The Jesuits were politically underground and pursued by the police?

B: Oh yes.

C: So you in that sense are going back to the Order’s history, the Jesuits’ history?

B: Yes, that is true, and at the same time I am trying to transcend that history, because I think in one sense we cannot in these times go back to old ideological issues. In other words, I cannot pose in such a time as ours these questions as sacred questions, involving what I conceive to be a kind of Platonic dogma—even though I hope I believe as firmly in the reality of the Eucharist as seventeenth-century Jesuits did; and that belief is still very much at the center of my understanding of my life. For me to be underground because of my position and deeds with respect to the Vietnam war—well, I find in that predicament a continuity of spirit with what other Jesuits stood for. But I don’t want to get away from something you were raising here.

C: I raised the issue of how people like me deal with violence selectively, in the sense that we notice the explicit violence of the political radicals, be they at the right or the left, and are not so willing to be horrified by the everyday violence that our government either wages explicitly or in its own way permits, even sanctions, here at home.

B: Yes, or maybe more concretely and more nearly to our own lives, I think that we are, many of us, struggling for a new sense of what a professional life is—whether it be that of the cleric or that of the medical person or the teacher or the lawyer or whatever. It seems to me we have a revolutionary situation in which there is an increasing awareness that the structures which purportedly support and extend and protect human consciousness, human dignity, human life, are simply not working on behalf of man; and at that point, if that understanding is verifiable, if it’s true, then it seems to me we are all in the same kettle of fish, and we each of us must move our professional life to the edge, so to speak, and begin again from the point of view of a shared jeopardy.

C: So you are asking how for instance a psychiatrist would do this. Well, you’re not asking that. I suppose I have to ask it of myself—how I would move my life and my work nearer to the edge.

B: I was thinking about my own life: on the one hand I grew up in a certain way, and until ten years ago I had calmly accepted the idea that renewal of the clerical state had to do with a renewal of the energies that go with compassion and understanding and human diversity. I believed that to be a good cleric was to be more available, more understanding—some of the things that come through in your articles when you discuss your profession. One was a good man in his life if his life was more and more available to others. I think that was right, that was sound—for the times. And then suddenly I began to realize something else which I still don’t realize very well, but which I find verified again and again. I keep going back to Bonhoeffer and to my brother and to Martin King and to all those breakthroughs which had to do with something we really don’t have a good word for.

But I can describe something that binds the three men I have just mentioned and others like them all over the world: they have dared accept the political consequences of being human beings at a time when the fate of people, of the world, demanded that one not be merely a listener, or a good friend, but yes, be in trouble. So, in a way I can only be thankful that my life has edged over to the point that I am now simply, publicly, church-wise, society-wise and outsider, a troublemaker, a condemned man. I say that, I hope and pray, not to be arbitrary, or romantic, or self-serving in a dramatic way, but in order to respond to a reading of the times, as Bonhoeffer tried to read the times. And I am trying to draw analogies out of history and other lives without being obsessive.

C: Or dogmatic.

B: Or dogmatic. One can be proven wrong; one can eventually find oneself mistaken. I will say to you that I would not be severely shaken tonight if suddenly against all the evidence of the past years I was to discover that I was on the wrong track. I would try to reverse that track, or get on another track; but I would also feel that it was more important to have explored this track than not to have. You know what I mean? To have entered into this present trouble with the law, to have entered into this anguish, to have entered into this separation from so many people I love—all of it has been necessary, I believe.

Even if I were to reverse myself or in an act of conscience turn myself in and make an act of obeisance before the court, before the judge, and ask for mercy and go to jail; even if I were to go back on something I have started; I would still say, or I hope I would: go ahead and reverse yourself, but learn from what you did and why you did it. I would still remain convinced that in view of what goes on in the world, we must each of us explore and prod the world, and enter into some kind of jeopardy. I would still have severe trouble with America’s political situation and its professions and its churches, and I would have to find another direction to make my misgivings real, to give them life through action. I could not remain at peace at the center—so the issue continues to be spatial—of one’s geography, one’s place, one’s decision to stand here, not there, and for this rather than for that. Where is one’s heart and soul at work—for what cause, however humanly in error at times? Again, the issue is geographic.

C: You don’t think that the problems you mention will always plague any kind of institution? Don’t we always move from the radical critic or dissenter—be he Christ, be he Luther—to consolidations, institutional consolidations, then to a serious decline of the radical spirit with a parallel rise in cautiousness and institutional rigidity? I suppose you are saying that your reading of the times is such that we require a radical and active critique of our society, and of a kind we may not have needed at some other points in the history of this society. Is that what you would say? Or would you say that at any moment in any society the kind of radical position of jeopardy you spoke of has to be assumed by various people if that society is not automatically to go the way of, say, the Russian Revolution or the American Revolution or the Catholic Church, and indeed every political or religious or professional institution that ever was or will be.

I am trying to distinguish between your statement about a particular moment of history in America today, and the problem you as a priest see afflicting your church—a problem which certainly afflicts psychiatry and psychoanalysis a short thirty years after Freud’s death, a problem which seems to rise once institutions become consolidated: they become cautious, inevitably dogmatic, exclusive, powerful, all too sure of themselves, abusive, rhetorical, and caricatures of the original intentions their founders had. Now how are we to distinguish between such a development in America, as a function of a nation’s 200 years of history, and the current emergency that you feel?

B: Well, I guess I could point to the fact that all kinds of people, people as diverse as nuclear experts like Oppenheimer and churchmen like Pope John, and spiritual leaders like Gandhi and Dr. King, expressed a common belief that the scientific revolution has introduced altogether new weapons against man, and new elements of jeopardy as far as human life is concerned. (We can all be killed, all two billion of us, in a matter of minutes.) It seems quite clear to me that we face something analogous to crises we’ve had before. But we also face something which we are justified in calling unique, and must deal with uniquely. I don’t want to fall into a kind of smug, self-contented state—and when one says man has always had to deal with these problems one is close to that kind of state. I want to say yes, we’ve always had these problems but at the same time, there is a uniqueness to the threat posed by American power right now—posed in Vietnam, but also in other parts of Asia, and the Caribbean and Central America and South America. (Look at the corrupt murderous dictators we support to the south of us!)

And I want to say as simply as I know how that I don’t feel in my bones a responsibility toward the long stretches of history ahead. I’m not responsible for what is going to happen to my words or to my “followers” or to my church or to my society in 500 years. I believe that my concern has to be with the here-and-now; as a man and a Christian I feel bound to look about me, learn what is happening to human beings, and then respond to what I see and learn with the acts, the deeds of a brother. I do not believe that learning is enough. One learns, I would hope, to discover what is right, what needs to be righted—through work, through action. What happens afterward is the responsibility of the people who come after. Here and now I am responsible, it seems to me, for my time and energy. The question I have to ask myself every day is this: am I putting that time and energy into the quest I know is needed for a new and more decent way of living? I am sure that “way” will have its faults and weaknesses—but they will be the next generation’s challenge.

C: Meanwhile, you have your responsibility as a particular human being alive at a particular moment in history.

B: Yes, and I believe I will be judged in accord with the attitudes I have shown, and the efforts in support of human life I have made, right here and now. I can only hope that what I do becomes part of what I guess can be called “the history of goodness.”

C: You say that you feel American power is uniquely dangerous to the world. I do not agree. I see American power as one element in the world, and one dangerous element. (Of course, all power is potentially dangerous.) But I do not see American power as uniquely dangerous—not when we have before us the spectacle of Soviet power, and rising Chinese power, and falling British power. How can one overlook the murderous greed we have seen the Kremlin display? What is one to make of the outlandish iconography Mao’s Peking unashamedly tries to impose on China, and maybe all Asia? Are Britain and France, with their hydrogen bombs, their waning but not dead imperialist ambitions, not a danger to many people in Asia and the Middle East and Africa?

B: Well, I am arguing that we are particularly dangerous as a nation—because of the nuclear resources and armaments we possess, and also because of the ideological frenzy induced in us by twenty years of a “cold war.” I would never deny that other nations are also dangerous. De Gaulle once said something interesting which I don’t think he followed on very well. He said that since the great powers use violence as their method in the world it is not at all to be wondered at when the smaller powers, the lesser powers, follow suit. I think that was a sensible reading of things. And remember, we are the “greatest” of the great powers, so it is our example that others follow. But the real question is what one does to fight the nationalist violence this world still suffers from so grievously. I never expect decent activity from great power, whether it be church power or state power.

C: Or the professional power wielded by associations of professional men (the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association)?

B: Not from them, either. It seems to me that if we are thoughtful human beings we look at those secret beginnings and comings-together, those pioneering communities of men and women, which are very mysterious and are very hopeful and which symbolize at least on the general landscape man’s goodness struggling for public expression.

C: Yet you see those efforts (those social developments, one might call them) as most likely doomed by whatever political success they may enjoy—because such new beginnings (Tillich would have called them), such hopeful expressions of freshness and honesty and openness are always subject to the corruption that seems to go along with success or power.

B: Yes, except that your word “always” is a very big word, and I am not sure history will bear out the necessity of using it. Sometimes I get the sense that in a way we are still part of man’s prehistory, and that we haven’t the faintest inkling of what man can really turn out to be like—except through the example of some of the saints, some of the world’s good men. Meanwhile we may have to muck about in the same way primates mucked about before the “first man” appeared long ago. So, that word “always” on the whole scale of things may be improperly used. What I am getting at is that I don’t accept the inevitability of, in a religious sense…

C: Of original sin.

B: O.K. Or let’s say its omnipresent hold over human institutions.

C: You think man can be better than he has been in the past or appears to be now.

B: Well, I would put it like this: I think there has not yet been a real revolution. I think that whatever we have achieved has been extraordinarily partial (and as you suggest, tied to sin) and that there has not yet emerged a movement, a movement of people with the spiritual resources to explore nonviolence systematically in every phase of its life. The very fact that we have to use that word “nonviolence” I think reinforces what I am saying. There is no positive word for the kind of human conduct an expression like “nonviolence” only begins to suggest. We can’t really put into words what we are struggling for.

C: Isn’t Gandhi’s word “satyagraha“—“truth-force”—a positive word or phrase?

B: Well, I can’t quite find the words for what I am trying to reach toward. But in general with regard to the movement it seems to me quite clear that I have to use expressions like nonviolence and I am dissatisfied with them because I think that we’re on the shadowy side of something which we haven’t stepped into yet. To push this thing further, I believe that it is entirely possible that the first instance of a really great breakthrough is going to take place in America. I say that because I think this war has really forced a lot of people to stop and think about all sorts of things—to the point that they may never again be the same, those people.

C: You feel optimistic about the possibilities in individuals, and by that I mean the radical possibilities. You feel we can significantly transcend what others have called our “finitude,” our psychological and spiritual limitations as human beings—limitations which have plagued even the best intentioned throughout history.

B: What would you think of an example like this? About a year and a half ago, after Catonsville for sure, I was involved in a retreat. We were gathered together, about thirty people—clerics and movement young people, students, activists—and we were discussing, because they wanted to discuss it, the direction of things after Catonsville, and where their lives might intercept with that direction. Someone told me in confidence during the retreat that present among us was a woman who was seriously contemplating self-immolation. This woman was just completing on this retreat a forty-day fast; she had taken only a little bit of water for that period.

I was asked whether I would try in whatever way I could to talk with her, because she had come wanting to talk but she couldn’t quite make the first overture. And so I did. I went walking with the woman, and she began to talk to me. It appeared that she had been in the movement for two or three years, had been brutalized by a very harsh jail experience—and yet she was filled with joy. That was what struck me, as I tried to understand and discuss things with her. After a period of time she mentioned that she felt there was a further gift to be offered—and that was the way she brought up the subject of self-immolation. Well, what I was looking for in her were signs of despair, signs of fear, signs of enough hopelessness to drive her over the edge, signs that she had lost her sense of herself. And yet I couldn’t find those signs in her.

C: You said you found joy.

B: Yes, I found the kind of joy that expresses itself in a remark she made: “I’ve done everything I know how so far and nothing has changed. Maybe a further act of mine will affect people; maybe if I show I want to give my life itself in this way, they will stop and think about their lives, this country’s life.” Even so, I continued to wonder whether this young person was not deeply troubled. Try as I might, though, I couldn’t find anything but wholeness in her. Finally I said this to her: suppose you were to find a community in which people were trying to go forward to something like we did at Catonsville, a community dedicated to nonviolence, a community whose members shared the anguish you feel. Would you join them and would you go forward with their discussions and their explorations and at least put off this plan you’re now considering? She said she would—and she did. I’ve lost contact with her but I am quite sure she has not immolated herself and has instead found that she can go forward with a certain group of young people.

Now why did I mention that girl in this context? I’m always searching for signs out of lives like hers that will help me to understand the limits of hope and the meaning of communities at the edge. I thought that I helped to lead her to such a community—a community which would free her of the need for that kind of ultimate expression. Obviously I was in great suffering about her contemplated action; I was convinced that it was neither necessary nor desirable.

You know, one remembers such a young person; she becomes a sign for one’s own life, a sign of what one can help others toward. Before I met that young lady I knew a young man who immolated himself out of what we could only agree was despair, and then another man, a Quaker, immolated himself at the Pentagon and my friends and my brother especially—he knew the man better than I—were convinced that he immolated himself as an act of hope.

C: So you do not look upon these people as necessarily deranged or disturbed?

B: No, not necessarily. In certain instances no, in other instances yes. I was at the bedside of a boy in Syracuse who immolated himself in front of a cathedral there—it was Easter of 1968 I guess—and I had been to Hanoi and I had seen what our bombs do, what our antipersonnel weaponry was doing to civilians, to children and their parents, and then I came home and this boy burned himself and he lived for a long time. I was compelled to go over and search him out, visit him. I got in because I was a cleric, even though he was in an isolation ward, receiving special care. I leaned over his bedside and I smelled what I had smelled in Hanoi—burned flesh. I then talked with him; and as far as I was able to piece things together his act was an act of hope, so he quietly and thoughtfully construed it. He was an honors student, a high-school senior who was not wild or overly good; “just sensitive” people said. I don’t know why I’m getting into all of this….

C: You are certainly posing problems for psychiatrists. I fear we almost reflexively look upon such people as “suicidal” or “crazy” or “psychotic.” (We have dozens of ready-made words to pin on just about anyone who comes our way and provokes us in one way or another—by puzzling us, or upsetting our neatly worked-out rationalizations, or shaming us, or making us feel lacking in some way.) But when an American soldier rushes into the arms of a machine gun nest with a flag in one hand and his gun in the other then he is a hero and by no means mad to us psychiatrists or anyone else. So what one person does to kill himself is considered insane and what another person does is considered patriotic or noble or sad rather than mad.

B: Yet I thought there were hints of extraordinary sensitivity and ethical concern in these young people; they were not going to sacrifice themselves in some wild, impulsive—or merely obedient and fearful—gesture. They had thought out carefully what they intended, and were almost serene.

C: I have no doubt that the doctors of the day could only consider Jesus mad; and so it has no doubt been with many of our saints, and indeed so it has been with many gifted men, among them Freud, who was called every name his fellow psychiatrists in Vienna (first) and elsewhere (later on) could think of.

B: Well, it’s as if the powers-that-be at any given time in history want to get rid of any challenge, one way or the other.

C: Not only the political powers-that-be, but the intellectual powers-that-be, also.

B: Or the spiritual powers-that-be—the church leadership, you know.

C: Yes, institutions are institutions.

B: There seems to be a sequence here whereby the first step is always to get “troublemakers” or “dissenters” out of the way by some means, whether it be by execution or expatriation or excommunication or whatever.

C: Or by confinement to a mental hospital.

B: Something like that, as the Russians quite commonly do now, and we ourselves have done. Then there is another very interesting step afterward; there is an effort to get right with history by rehabilitating those people, once they are dead or no longer dangerous. You canonize them after you’ve exhausted them. What you really can’t bear is to have them around.

C: Yes, and both Dostoevsky and Shaw have described the details of the whole farce—and tragedy—quite well.

B: Yes, anything not to have up close, real up close, a moral pressure of sorts—in a person or a community of people.

C: What might professional men do—in the tradition of your deeds? Or is it impossible to prescribe for others? I mean, you have taken a step as a clergyman in relationship to the law, the federal law. You did something, were judged, were sentenced, and have now taken a position in what you call the underground. Could you let your mind wander for others?

B: Could I again point to some examples? William Kunstler, who was heavily involved in the Chicago trial, was also on our legal staff, and he seemed deeply moved by his exposure to us. He went out to the Milwaukee trial after our trial and he defended those people out there, and then he went on to Chicago. But I don’t want to talk about his public record, but rather what occurred as he talked to me during the time of our trial. I guess I was perhaps his closest friend in our Catonsville group, and the one most available.

He wanted to talk to me not only about what it meant for me to do what I did at Catonsville, but about broader issues, like the purposes of the worker-priests in France. He asked about them, and I said yes, I was over there and knew many of them, knew them at their hour of greatest trouble in 1954, when they were facing suppression by Pius XII. Kunstler said he’d done a certain amount of reading on the worker-priests and I suggested further reading and he did the reading. He was intrigued with the professional implications of the struggle waged by the worker-priests; he wanted to apply their example to himself and the legal profession in general. Certain clerics had moved to the edge of the clerical estate and had joined a very different cultural and political and religious scene, and were finding out what it was to be a priest under very tough conditions. Perhaps, he thought, lawyers should do likewise.

When I met him a few months after the trial he said: I want to show you the text I have of a talk I gave at Harvard, at the law school. In the text he drew upon the analogy of the worker-priests over and over again. What he was moving toward in his own life was what later became the “lawyers’ caucus” in New York. He moved out of his lawyer’s office on the East Side and went over to a loft on the West Side—in a very different neighborhood, in the company of a few other young lawyers. They set up an office which will be increasingly available to poor people or people waging a struggle against America’s military and political foreign policy. Kunstler had decided he could not remain at the center of his profession—and embark upon occasional expeditions into extra-curricular political activities. He had decided that his whole life must move over. I found that decision very sound; I found it very much like what happened to me.

I’ll never forget, by the way, what happened when I came back to Cornell after the trial. The law school refused to look at the issues we were trying to raise. When the law students tried to get a mock trial going about the issues at Catonsville—because I had taught at Cornell—the law professors wouldn’t cooperate. The students had to get a lawyer from somewhere out of town to come in and talk about the political issues we had tried to raise. The law professors would only appear on the side of the prosecution. Once again I saw how much attention professional men, including teachers, pay to the status quo—however “fair” and “objective” and “truth-seeking” those men say they are.

No wonder I gradually began to realize that I had to do more than give lectures and write and speak—however well, however compassionately. I had to move. I had to take risks. The challenge was geographical. The challenge was to place myself in a position of jeopardy. I had been a counselor of young people for many years; I had tried to be available and tried to understand and tried to learn. I eventually discovered that such efforts weren’t really to the point now, so I began to say—first of all to myself and secondly to the Jesuits—that our whole scene has to move over. In order to become men at all we’ve got to become political men, because that’s where the action and the struggles are and that’s where the edge is.

C: Such a decision, or move, if made by professional men, would confront them directly with their society and with the courts and with police and also confront their families. How are middle-class children going to fare when and if their parents take political stands which involve the risk of prison and the sacrifice not only of career but even of enough money to get by? For that matter, how do the individual professional men themselves fare? You would probably say that they don’t do it as individuals. I note you brought up an example of a group of lawyers. I suppose those lawyers had to come together not only as professional men; I mean, their families have to come together in some way, too.

B: Right. And I think lawyers need help in such a struggle from others, from doctors or teachers, from workers of all kinds.

C: Do you see any real developments along such lines right now?

B: If you or someone had asked me even five years ago what group of people is most intransigent and hopeless, so far as all this is concerned, I would immediately have answered clerics, clerics obviously. And I would have answered with despair. But then all of a sudden something happened, and clerics were at Catonsville and clerics were at Milwaukee and clerics were in Chicago, clerics were all over the place—not in great numbers, true, but they were there, and that to me evokes hope. I wonder what I would say today if someone asked me to name the most intransigent, hopeless group of people.

C: Perhaps you would say psychiatrists?

B: No, I would say that the problem now is not a particular profession, but the family.

C: You see the family as a stumbling block.

B: I see the American family as an institution in the same impasse that the churches are. These are obviously very clumsy reflections, but if we are talking about which structure in our society seems to offer the greatest resistance to change I would think it is the family. I don’t mean that the family isn’t changing; I mean that in a consumer society, the family is the means by which most people become tied to a cycle like this: go along with things, so long as you get enough to buy more and more things, even though the whole world is exploited so that a relatively small number of people in this country—us!—can live well. (Our own land and air and water are also plundered in the interests of the same kind of blind consumerism.)

C: What you would say, therefore, is that what keeps someone like me from the edge is not so much the various ideological rigidities of my profession, or the way it lends itself subserviently to a certain kind of social system, and in fact allows itself to be used as a means of judging people within that system—by calling them mad if they are social critics and calling them deviants if they express their political resistance too strongly, in short by calling them all kinds of psychological names which are really politicized names and pejorative names.

Again, you are saying that it is not such things that really count. You claim it is because I am a husband and a father that I am cautious. In another sense of the word I “husband” my resources and remain loyal to the system, the social system, the economic system, out of fear, out of trembling for my children. I become increasingly tentative and cautious as I try to bring my children up, get them into the system, preserve for them the privileges I’ve inherited or won for myself. Furthermore (if I follow your line of reasoning) as a burgher of sorts I’ve learned to control carefully my mind and its particular persuasions, its beliefs. Regardless of how sincerely I hold my opinions, in the clutch I hold them not out of sincere and open-minded conviction but because I have to—as a landowner, a householder, a husband, and a parent who lives a comfortable life in this particular nation. Hence I am very cautious indeed about criticizing this society too broadly, too vigorously, too thoroughly. After all, I want all its advantages—for my children, of course! So, I carefully, maybe semiconsciously, calibrate how far “out” I dare go politically. Is that what you’re saying?

B: Yes. And I think marriage as we understand it and family life as we understand it in this culture both tend to define people in a far more suffocating and totalizing way than we want to acknowledge. There is a very nearly universal supposition that after one marries one ought to cool off with regard to political activism and compassion—as compared to one’s student days, one’s “young” days.

C: Married men to a degree lose their social compassion?

B: Yes. Many of them feel that after marriage their interest in social issues has to be “extracurricular.” Admittedly I am not married, but I see no reason why, in the nature of things, what I have just described should be so. I see why things are as they are now, in this particular country. But I think things are changing. I have to get vague here, even a little mystical, some might say—but it seems to me that the biology of the spirit is really exploding in this country, hence the inner turmoil that is all around us today. Biologically and spiritually we are trying to break through to another stage of human development. I think we’re in a period when on the one hand everything in the culture seduces us into non-experimentation or into irresponsible experimentation which is the same thing, and on the other hand something deep inside us says we’ve got to live differently, not in one little fiefdom after another on one plot of land after another.

We have signs about us: the communal experiments of students and of younger people, for instance. More and more one hears that the goods of the world belong to the world and that the parceling out of these things into arbitrary units is not even helping us, let alone other people. More and more one hears people question the point of all this acquisitiveness. The sharing of life, the sharing of goods, the sharing of spiritual experiences is becoming something important to our young. Drawing on the experience (for example) of David Miller, who was married before he went to jail—they had one child and the second on the way—I see no reason why the political and religious passion of a man like him should be dampened by the fact that he is now a husband and a father. Indeed, because his wife shared his views, because he and his wife were protected by a larger community, his going to jail I believe marked a period of real growth in the man. I’m obviously not arguing here that it was good for David to go to jail; but worse things have happened to people outside of jail—because there was not a community around them and because they were simply caught up in the cruelties and exploitations of our society.

C: So you are not really arguing against the family per se. What you are arguing for, what you are saying, is that a husband and wife can maintain their own sense of privacy with their children and yet also maintain a kind of political passion which you think necessary.

B: I would think so. Again, I hope I am not arguing abstractly or as a priest who doesn’t know a thing about the demands of marriage. I’m arguing as one who knew well the married members of the Catonsville Nine; they were with me and I with them, and I saw what married people could do, together and in defiance of what all those commercials on television show going on between husbands and wives and children. Maybe man at the peak of manhood is most revolutionary, and his passion for change may live side-by-side with marriage, or he may want to postpone marriage. I don’t think he has to stay single, though.

C: You’re saying that some men at the peak are revolutionary. Clearly, many aren’t.

B: All right, let’s say I’m talking about an ideal man, a heroic kind of man.

C: Talking about some versus many, I’d like to ask what one thinks or does about a nation whose people, perhaps like people everywhere, are mostly not “ideal” or “heroic”—in this case a nation whose majority is comfortably enough situated to be reasonably content politically. I guess what I am saying is that I think we are basically a very conservative country. I think that by and large the people in this country are conservative, do not want radical change of any kind, are well fed, well housed, and on the whole satisfied with things as they are. Not that they don’t want changes here and there; but in the main they feel satisfied with the life they have, and unwilling to have you or me or any other smart-aleck intellectual come along with our brainy ideas, so often spoken so damn self-righteously and with such damn condescension.

I have to contrast the way someone like Herbert Marcuse writes about the ordinary working-class man in an industrial society like America and the way those men and their wives and children actually talk about themselves and their lives. To read some social critics, life is so dreary and empty and routinized and fearful in our lower-middle-class suburbs. To read them, drones live there. I wonder how many factory workers Marcuse spent time with before he constructed those elaborate theories of his. I wonder how much time he took to witness lives, the everyday lives of people. I see joy and humor and affection and liveliness among the working people I visit in their homes; they are not the people some of our radical critics would have them be.

(To be continued in the next issue.)

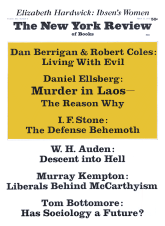

This Issue

March 11, 1971