With his new novel, C. P. Snow has reached the end of Strangers and Brothers, a solemn, Edwardian sequence of eleven books, first conceived in 1935. Last Things. It is characteristic of Snow’s lack of moral or literary tact that he can suggest an eschatological climax when he is merely finishing off a thick slice of middle-class English life. Earlier in the series, in The Affair (1960), he took the Dreyfus case as a model and backdrop for a squabble in a Cambridge college. He is aware of the distance between his small, prosy world and his grand allusions but insists, nevertheless, on comparisons, on suppressing differences. Cambridge, the Vatican, the Politburo: all instances, he says in the new book, of closed politics, “much the same.” Generalizing of this kind has been his idea of what a major novelist ought to be doing. He has set out to be the George Eliot, or at least the Galsworthy, of his generation, to write nineteenth-century novels for a later day—a slightly alarming ambition but not in itself a silly one, since a case can be made for conventional forms so long as there are conventional realities left to be explored.

What goes wrong, then, apart from the failure of tact? The answer is Lewis Eliot, the heavy-footed hero and narrator of these novels. The “inner design” of the whole work, Snow wrote in a note to The Conscience of the Rich (1958), does not lie in the “attempt to give some insights into society,” although that is important. It lies in a “resonance between what Lewis Eliot sees and what he feels.” This is unfortunate, since Eliot doesn’t see half as much as he thinks he sees, and what he feels is severely circumscribed by his complacency.

Indeed, Snow seems to worry that Eliot may appear smug, and shows him beating his breast as often as he can. But this doesn’t help matters. Even the keenest self-accusations turn into subtle self-praise, and only when Eliot’s self-congratulation becomes a theme in its own right do these novels come to life. The books then turn quietly lyrical, quivering with a delight in social success—and why not? Eliot’s description of the House of Lords, for example, in Last Things, does not evoke the House of Lords for us, or even the feeling of what it is like to be there. It does evoke, unintentionally perhaps, the pleasure of being able to talk about the House of Lords in an offhand manner. “It was a Wednesday afternoon, about half-past five, the benches not half-full, but, as peers drifted in from tea….”

Lewis Eliot is a Dick Whittington, a poor boy who has made good and is proud of it, and, paradoxically, his strongest quality as a person dooms him as a narrator. Throughout the series, Snow makes much of the idea of a healthy selfishness, which is what characterizes Eliot. An enviable quality in many ways, no doubt, admirable in a nurse and useful in a friend. But a disaster, plainly, when it belongs to the central consciousness of a set of novels professing to deal with seeing and feeling. In Last Things Eliot, now in his sixties, has a difficult eye operation, and suffers a momentary cardiac arrest. After an acute panic and depression, he comes to view his return from death as a privilege, as the source of new serenity. An interesting thought, which loses almost all its force here because Eliot has always been serene in this sense: kind, well-meaning, decent, but ultimately impervious to major emotional weather.

As for the “insights into society,” they run from a blurring of contemporary history (Cambridge, the Vatican, the Politburo) to a rudimentary social psychology bearing predictable news. In The Masters (1951) we learn that unlikely people are often brave in war; in Homecomings (1956) we learn that suffering is repetitive, that ingenious men often underrate people around them, that “no imaginative forecast of what a life will be is anything like that life lived from day to day.” Indeed the structure of Eliot’s insights varies very little. There is what people usually think. There is what Eliot knows. What Eliot knows is the opposite of what people think, and he is right. All that remains is for him to pick up the bouquets which are thrown in these novels with great frequency. “I trust Eliot’s judgment,” people say stoutly. Or: “You’re very observant, aren’t you?” Or: “Even a man like you, Lewis, who has, if I may say so, more than his share of the gift of understanding….”

Yet Strangers and Brothers, while falling well short of its high intentions, is never quite so bad as it ought to be. The characters are dull and the prose is dead, but we keep on reading, or at least some of us do. Why? Snow is often intelligent when he is not being empty and portentous, as when someone remarks in The Masters that gratitude is not an emotion, but the expectation of gratitude is. He is a competent, if uninspired, technician—it is worth remembering that his first published fiction was a detective story—and he still puts his plots together efficiently. Better still, he has a patience with trivial detail, with the minutiae of daily life, which, on one view of realism, gives him an edge over Flaubert, who was too angry to leave things alone, and even over Balzac and Zola, who always let their myths loose too quickly.

Advertisement

There is a sense of life being lived in Snow’s work, however stiff and stupid that life appears. There is enough drinking, for example, to make Malcolm Lowry look abstinent. There is also a busy sense of gossip. I once thought the attraction of Strangers and Brothers was the promise of an inside story—inside Cambridge, inside Whitehall, inside the Jewish haute bourgeoisie in London. In fact, Snow never shows much of the inside of anywhere. Intimate political conversation in The Corridors of Power (1964), for instance, covers such subjects as the Tories’ chances in the next election and whether a British hydrogen bomb makes any strategic sense—matters discussed at the time in most pubs in England most nights of the week. No, the sense of gossip is purely a sense of gossip. Even if you know the inside story, even if you don’t but couldn’t care less, these novels work in the same way: their pace and style suggest an invitation to eavesdrop. The novels pretend to be letting secrets slip out, and, while they don’t, the illusion is appealing.

Last Things, however, is a falling away from this small, but not negligible, achievement. It is a wistful, tired, uncertain book. Old characters are wheeled on to take curtain calls. Old themes are battered into the ground. Life and death, young and old, take your pick. Eliot’s father-in-law attempts suicide and later dies. Eliot himself turns down a ministry in the Labour government—the time of the action is 1965 to 1968. Eliot’s son is involved in militant student action, his stepson marries a cripple. Various marital and sexual relations are canvassed before the book reaches its intended peak with Eliot’s cardiac arrest and closes with his son’s departure to begin a career as a journalist in a world that is rapidly changing. “This wasn’t an end,” Eliot reflects, having seen his son off at the airport. “There would be other nights when I should go to sleep, looking forward to tomorrow.” The cliché is, in its way, a fitting finish: the thinking man’s version of the sunset at the end of a movie.

If C. P. Snow looks vaguely back to George Eliot and Galsworthy, perhaps to Proust and Duhamel, Rudolph Wurlitzer and William Melvin Kelley in their new novels look directly back to their masters—so much so that it is not easy to see these books as independent works. Wurlitzer makes good on his huge debt to Beckett by translating that old mourner’s metaphysics into American myth and psychology. Kelley remains in the shadow, much larger in any case, of Joyce.

Nog (1969), Wurlitzer’s first novel, was a journey to the end of America—literally to the Pacific, seen as a last boundary, and to the limits of an idea. If America for Fitzgerald was a willingness of the heart, for Wurlitzer it is a dream of movement linked to a faith in an infinite environment: there will always be somewhere to go. Except that there won’t be. Both novels are about what happens when you realize that there is nowhere to go, although Nog is about reaching that realization. The new novel, Flats, is about living with it.

Minor landscapes in Nog, scenes of ravage and ruin, have taken over in Flats. There is gunfire, a smell of burning rubber. There has been a battle, or a holocaust, some calamitous occasion timidly referred to as a “small disaster,” a “separation,” a “transgression,” a “fabulous mistake.” The scene is the flats, “west of the city.” A spectral Beckettian narrator meets equally spectral figures, groping among the debris of a modern civilization: oil pumps, egg shells, dumped cars, paper plates, ice boxes, a smashed statue, an abandoned factory. There is a road, a swamp, a field, a creature in orange socks in a broken armchair.

The narrator struggles to set up connections, to make a camp, a community, shifts his identities like a sequence of masks. He calls himself Memphis (“a root, a pretension”), Omaha, Halifax (“There are no surprises in Halifax”), Wichita, Duluth, Houston (“Houston tends the store. Houston is a changing and determined city”), Portland, Mobile (“Speech is slow in Mobile”). Steady places all, emblems of a dreamed equilibrium between moving and staying, names in the narrator’s mind for a series of subtly changing strategies for living with others, now that there is nowhere to go. But they don’t help. They are only hopes, metaphors. Or rather, they help to see the narrator through to the dawn, when the book stops, and that is perhaps as much as one can ask for at the end of the world. We are meant, I think, to see all this as a large double portrait: of a state of the soul, a night in the life of a dispersed and fragile mind; of the state of a country, America surveyed by a last derelict pioneer.

Advertisement

Like Beckett, Wurlitzer is often darkly funny about his images of despair—“I don’t like the way things are going,” the narrator says when a turtle arbitrarily appears in the text—and my only real quarrel with his book is with its tendency at times to explain too much, to slip too easily into abstraction and analysis. “Omaha is as afraid of expansion as much as he is of contraction.” “It’s as if this localized hysteria results from not managing the space behind me and not transcending the one in front of me.” The flatness and stiffness of the vocabulary are intentional, of course, an irony, a reflection of the helplessness that is the novel’s subject—words miss reality just as the characters miss each other in the darkness.

But sentences like the ones I have quoted—and there are more—are finally too flat. They try to evoke dullness by being dull. Flats is a book which relies heavily on strong but oblique suggestions—on its being set, for example, in the aftermath of what could equally well have been a bad trip, a nuclear war, a nervous breakdown, or the last paralysis of the modern city. This means that it will stand only so much explicitness, and although the occasional failures of the novel’s language don’t damage it seriously, they do threaten it, and Wurlitzer’s success becomes more fragile, less immediately convincing than it might have been.

Dunfords Travels Everywheres picks up the motto of Finnegans Wake in its title, points to Joyce in an epigraph, and even bravely attempts the late idiom, making a rumbling, punning amalgam of minstrel paper, journalese, advertising copy, and radio serial into a new language, an escape from “languish,” from the “Langleash langauge,” a descent into a racial collectivity of blacks, the tongue of New Afriquerque cropping up suddenly in the ordinary prose of the novel.

What is needed, Kelley suggests, is an “Unmisereaducation,” which I translate as a re-education away from miserly misreadings. The twin heroes of the book, Chig Dunford and Carlyle Bedlow, Harvard black and Harlem black, traveling writer and likable lay-about, aspects, ultimately, of a single self, meet on the common ground of their color and their alienation. Both of them, in the book’s view, are playing the white man’s game in their different ways, and only at these muttered, barely intelligible levels, where they and the rest of their race are one, do they know how fully this is so.

In the half-gibberish of their dreams, represented in the novel by Joycean metalanguage (“You canntbreak yEggs like Dhat, man. You dumpty ySelf when you nthumptyng yon energingerbread Lady”), they know the truth which escapes them in waking life—shown here by Kelley, in more conventional prose, as a place of assassinations and deceit, where slaves are suddenly encountered on a lower deck of a modern liner, where vast competing conspiracies, secret societies of whites against blacks and vice versa, are glimpsed beneath the surfaces of an innocent-looking world.

There is an affinity with Joyce. Kelley, too, as a black American and a writer, is caught in the language and culture of an enemy country, and his use of Finnegans Wake reflects a legitimate distress: it is a mockery both of “good English” and of black manglings of it. The trouble is that the effort looks in the wrong direction. The experimental idiom is ingenious, but it is, also, thin and obscure.

The novel opens in an invented European country where the natives say things like “To the Giants of Frost, my sirs!” meaning a toast to the two major protagonists of the cold war. The best part is a picaresque narrative about the Devil in Harlem. Kelley’s real gift is for evoking an uncomplicated tenderness—there are remarkably drawn old men and children in his short stories—and for grand, improbable, epic exaggeration: the sudden sight of slaves in this book, or in his first novel, A Different Drummer (1962), the exodus of the entire black population from a Southern state. From a man who can do these things, Dunfords Travels Everywheres seems gratuitous, an attempt to be new at all costs. Homage to Joyce? A book more clearly Kelley’s own would have been better.

Blue Movie is Terry Southern’s return to the novel after a long spell among screenplays. It shows touches of pedantry, picked up in Hollywood, quick explanations of this or that arcane term. But mainly it is a marvelously inventive comic caper, with a battery of ripe characters and a manic and well-made plot.

Southern’s central proposition continues from his earlier fiction: life is an inescapable soap opera, inflated and heartless, and you have to take your humanity where you can find it. A boy and a girl, in his first novel, Flash and Filigree (1959), become timid young lovers only after a rough and circumstantially displayed rape. In Blue Movie coarse, horrid Sid Krassman becomes something like a spokesman for normalcy because he can still be shocked by necrophilia. Yet the new novel is different from his earlier work. Southern’s previous response to the soap opera was to tamper with the story from within. Since we are locked in a bad film, why not make a dent or two of our own in the script? Why not take a howitzer on safari, as Guy Grand does in The Magic Christian (1960), or slip a panther into a dog show, or bribe two big and hairy boxers to go gay and fall around effeminately in the ring—two more of Guy Grand’s tricks? Or write a book like Candy?

In Flash and Filigree, Dr. Eichner, after a minor but disturbing brush with the law, stumbles into more or less accidental murder. He realizes that he cannot, “in all conscious sincerity, again risk delivering himself into the judgment of others.” He lies to the police, disposes efficiently of the body, goes home and sleeps contented, “like a tired lover.” The principle is the same as with the practical jokes. You are given release in feeling secretly superior to the mean, cliché-ridden world around you.

There was an aloofness, then, about Southern’s earlier works, bright as they were, a defensive elegance both in the main characters and in the prose, as if life and language were to be viewed only from a sterile distance, as if pastiche were the only civilized mode left to a writer. The results were funny, but often icy, and this is what has changed now. There is a writer in Blue Movie called Tony Sanders, and I assume the initials are not an accident. Tony is up to his eyes in the mess the novel depicts, and Southern’s language here is no longer ironic or mocking. It is comic, rich and fluent, full of jargon and gags, but it is a language with a life of its own, not a series of echoes. If the soap opera is all there is, then rewriting pieces of the story is a trivial or temporary revenge, and how to live with it becomes the urgent question.

An actress commits suicide in Blue Movie, caught between the different but equal savageries of her brilliant director and her moronic studio chiefs. Tony, the writer, breaks the news with an embarrassed, joking allusion: “…it’s about Angie…she did that famous Big Sleep routine. Know the one I mean? Made it too.” The weepiest response in the worst kind of pulp could hardly be less adequate, and this is indeed the general drift of the novel: the sincere jokers, the artists of the day, do no better and may do worse than the insincere sentimentalists, the pushers of corn and wholesome tears.

Boris Adrian, great, sad, phony, weary film director who has not found satisfaction in his spectacular success, is making the ultimate erotic movie in Liechtenstein, pursuing truth and beauty where others see only dirt. The others are right, of course, there is only dirt, and the irony of the novel rests on the gap between this fact and Boris’s pretentious ideas. The point is not that you can’t make a truthful and beautiful movie about the most intimate moments in sex—Southern seems to suggest that you can—but that making such a movie would be an inhuman activity, which it becomes in this book: a clinical cruelty under the alibi of art. The work is full of violence and humiliation sanctioned by thoughts of the future film.

Still, we shouldn’t insist too much on the message. The extraordinary verve and hilarity of Blue Movie can too easily be seen as merely a mask for a high-toned despair. There is some evidence that Southern wants us to see it this way—a poker-faced epigraph from T. S. Eliot, a suggestion that reality is not a laughing matter, that “he who laughs has not yet tuned in the Honkly-Brinkley Report.” But he can’t be serious. Here, as in all comedy worth the name, the hilarity outrides and contains the despair, while the despair makes the humor human, and not simply trivial.

The novel itself has none of the self-deceiving pretentions of the movie it creates. It is relentlessly pornographic, making Candy look about as blue as Lassie Come Home. Indeed I found the pornography a bit wearing. Still, it’s a small price to pay for this fantastic spree—a book about a film which seems to defy all thoughts of making a film out of it, the hottest property, as one of Southern’s Hollywood characters says of another promising script, since Dante’s Inferno.

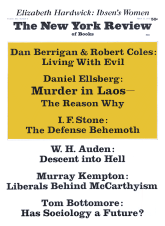

This Issue

March 11, 1971