“And Where Were You, Adam” and “The Train Was On Time” are described as novels, but it is better to read them as novellas. I am sure that Herr Böll wrote them with a sense of their participation in that genre. The novella is neither a novel nor a short story. It distinguishes itself from each by listening to its own rhythm, it has its own pulse. Measuring time, it does not count pages. A certain rhythm is to be fulfilled: it is a matter of tact, a propriety of form, that the writer practices whatever degree of austerity is required in the fulfillment. He understands the genre, and he assents to its limitation. As for content, the main limitation is that the form goes better with ends than beginnings; if life is a five-act play, the novella comes in with act 4, and stays to the end, fulfilled in death.

In Herr Böll’s novellas, act 4 is 1944, and the remnants of a German army wait for the end in a village in Hungary, or Poland, or wherever. One life is equal to another now, rank is an anachronism. Captain Bauer’s skull has been ripped open, nothing left but the word “Byelyogorshe,” repeated as if it had cabalistic significance; and perhaps it has. Sergeant Scheider is blown up by a mine. Feinhals tries to go home, his Jewish girl Ilona is shot, he reaches his doorstep, is killed. In Lyov, Andreas meets a prostitute, Olina, they live for a few hours by speech and feeling, then they are killed.

As Herr Böll practices the genre, his most congenial materials are a soldier, a girl, and the year 1944. The pattern is like a fist, clenched then slackening, the fingers opening as life crawls to the extremities, and dies. Feeling shudders in memory, scenes from childhood, home, daily joys of routine. Andreas postpones his death by recalling what life meant on its high occasions. Lieutenant Greck goes for a ride on a swingboat in the middle of a hot day in a dirty Hungarian village. SS Captain Filskeit runs a concentration camp, but his secret life is in music, and he makes Ilona sing for her few days’ grace.

These are snatches of life, samples of good and bad, they affect the tempo of the story, subject to the grand design of rhythm. They also account for the remarkable density of these short fictions; as samples, they testify to lives beyond those which are given, other people, other villages, casualties of love and war. We live in an old chaos of the sun, as Wallace Stevens wrote. Like Greck, Bauer, Scheider, Filskeit, we are remnants, in the wrong sector, some astray in the head.

Of the two stories, “The Train Was On Time” is the more powerful, mainly because its companion piece is tempted to become a parable, and yields. In “And Where Were You, Adam,” Feinhals comes to his father’s house, sees the white flag hung out to anticipate the victors, falls as the sixth shell is fired, dies with the seventh. He sinks upon the threshold of the house, the flagpole has snapped, and the white cloth falls upon him. The last pages of the story are emblematical of love and war, indeed, and the most ordinary trees turn into forests of symbols: it is too much. “The Train Was On Time” is a more concentrated story, and we do not feel a disjunction between figure, image, or symbol. We attend to what is going on, but we are not required to distinguish between one mode of reality and another; we respond to the cadence, and that is enough.

It is my impression that in this story, more completely than in “Adam,” everything has been consumed in the form, there is no remainder, no waste. Herr Böll’s sense of life is powerful, and he is an artist, but he is consummately an artist when he hands over every detail of his story to the form: whatever the form retains, shall be retained. Form in such an artist is his conscience, and he submits to it, knowing that it is older and wiser than he. What form gives him back, in return for that confidence, is the meaning of the story, certified by an entirely personal intonation.

If one of these stories is richer than the other, while both come from the same source, the reason is that in one the relation between imagination and form is a deeper, more trusting relation; in the other, there are mental reservations, privacy, privation.

Paul Horgan’s Whitewater has so much going for it that I am surprised it has not gone farther. It is a story of three young people and a guardian angel. Billy Breedlove is a wild boy, and with that name we are meant to care for him, but it is heavy work loving a barbarian. Phillipson Durham is the quiet one, everybody’s second choice, a scholar who will write a great work on William Beckford, author of Vathek. The angel is slow, but she arrives in time to save him. The girl is Marilee Underwood: when Billy dies, she drowns herself. Mrs. Jim Cochrane plays the angel, and she is perfect; she reminds me of the countess in Christopher Fry’s The Dark is Light Enough, another perfection. It must be hard to hate Mrs. Cochrane, but I found myself driven to it after the third visit to her great house, full of moral platitudes and impeccable taste. I would care for Phillipson much more than I do if he showed the least spark of revolt from that good angel of his.

Advertisement

It is hard to fault Mr. Horgan for doing everything right. When he mentions Belvedere he tells us that it has a population of 5,453, and I approve of facts. In the opening scene he describes “Fourth Island in Whitewater Lake, which backed up Whitewater Dam, on the Whitewater Draw, forty-nine miles from the town of Belvedere, in Orpha County, in West Central Texas.” If we praise that kind of thing in Defoe, we must praise it in Mr. Horgan, it comes from good motives. But it does not ring true. After a while, these details in Whitewater begin to sound like abstractions, arithmetic drifts off into metaphysics. I think the reason is that Mr. Horgan’s sense of life is generic rather than individual, he takes an interest in people only because they constitute Man; or so the fiction suggests.

Phillipson, at the end, is musing to himself about the first scene, the two boys out on the lake at night. “Those two are like memories of everyone else, somewhere, some time, aren’t they?” he asks. Well, yes, they are, but they were more vivid in the first chapter, before they acquired that general burden of mankind. Near the end, Phillipson has a rather pretentious conversation with Mrs. Cochrane about Vathek, and he declares that he does not intend to become a voluptuary. Mrs. Cochrane, delighted to hear such splendid words, sees in him “the possibly lyric but authoritative scholar, social historian, and teacher he was to become, whose doctoral thesis on William Beckford would lead to a row of well-regarded books on the precursors of neo-Gothic Romanticism, in literature, painting, and architecture.”

One of the attractive qualities in Mr. Horgan is that he can give his characters such thoughts without a trace of irony. The next sentence reads: “It would always be marvellous: what could come from what.” Mr. Horgan defends this sentiment in Mrs. Cochrane because, I think, it is his own. He gives it to Phillipson a few pages later. “When there is a peaceful moment in which to think about it,” he writes, “Professor Durham reflects that even the great lives of long ago were once colloquial; and then the sense of their agitation makes him feel the tug of the familiar, the unevaluated time of his own youth—names, places, all—as though it too must be historically precious: the commonplace become legendary.”

This is what Mr. Horgan tries to do in Whitewater, tries to tell a commonplace story in such a way that it becomes legendary, and the colloquial style becomes sublime. But the trouble is that legends cannot be forced; they come or they do not. Mr. Horgan coaxes the commonplace to transfigure itself; when two boys are together he says that they are “content in the lordship of solitude,” but the wretched fellows still remain two commonplace lads out on a lake, not Robinson Crusoe and Man Friday. There is a feeling, toward the end of the book, that Mr. Horgan is putting in the significance which the story itself failed to give; details are underlined, glossed, pondered, lest they die as details.

Henry James, considering the novel as a picture of life, said that it is not expected of a picture that it shall make itself humble in order to be forgiven. But Mr. Horgan’s picture makes itself grand in order to be noticed. Judging from the style, I conclude that Mr. Horgan has misgivings about his fiction. He worries that perhaps it will not mean enough or mean it abundantly. He has good will, good nature, powers of reflection, and he cares about the quality of life; what his writing lacks in Whitewater is nonchalance, the ease which succeeds difficulty. He writes as if there were nothing, no release, beyond difficulty.

There is very little difficulty in The Dick. Kenneth Sussman, a young lieutenant in Army grain supply, changes his name to Ken LePeters, “taking the name of a magic boy who had appeared long ago to his old New Jersey neighborhood, rallying a scraggly, thin-chested corner football team to thrilling, towering victories over richly equipped monster Catholic squads, then vanished, as though in smoke, at season’s end.”

Advertisement

The new magic boy goes East as a public relations man to a homicide bureau. He has a boss, an assistant, a wife, a daughter. His wife has an affair with Detective Chico. Ken becomes a real detective, gives it up, runs about as a voluptuary, tracks Chico, shoots two of his toes off; then takes his lovely daughter out of school and rushes away into the white spaces at the end of the book.

Mr. Friedman writes with American verve, he drives his style as if it were a fast car. His common talk is fast, the book offers lots of chuckles. Even the printer knew that he had a Le Mans job on his hands. The type face, we read, “avoids the extreme contrasts between thick and thin elements that mark most modern faces and attempts to give a feeling of fluidity, power, and speed.” The speed I recognize, fluidity yes, but hardly power.

The trouble with The Dick is that it has no subject, no content, it is about nothing. The book is all margin, no text. The fragments fly past, but they do not cohere at any point. It is significant that Mr. Friedman tells us everything about Ken’s vacancy, but nothing about his job; plenty of sex life, but no life. The paragraphs are lively while they last, but it is easy to forget them. The only character for whose fate it would be possible to care is the daughter, Jamie, and it is clear that she will come to no permanent harm. Once that is established, the history of Mr. and Mrs. LePeters is something I can contemplate with indifference; whether she returns to Ken’s nest, or goes off permanently with Chico, is a matter of literary indifference, whatever a moralist chooses to make of it.

“What am I supposed to do?” the erring wife asks her husband.

“I can’t help you on that,” Ken says, and he guns the car away. A few minutes before, the wife had put up a fight to save the home.

“You don’t see it at all, do you? That all of this was just for us. So I could be a better wife.” I would not take her back after that line: adultery is bad enough, but a woman emitting those lines deserves hanging.

It is not clear what the ghost of Henry James is doing in The Ghost of Henry James. His own apparitions are formidable presences in “The Turn of the Screw,” “The Jolly Corner,” “The Friends of the Friends,” and other stories. Mr. Plante calls James to cast a spell upon the proceedings, but I think he has not been prudent. Presumably the point is to write the kind of story that James might write if he had the luck to live in 1970, free of social restraint. He might write of a family, four brothers and one sister, Julian, Charlotte, Charles, Claud, and Henry. He would dispose of the common problem, money, and urge his presences to live, playing Strether to their Bilham. Perhaps he would devise tortuous relationships; Henry and Baretti, Claud and Frances, Charlotte and Louis, Charles and Colin, the names do not matter. Add a bit of travel, London, a mansion in Italy. Make the sex diversely heterosexual, homosexual, and on one occasion incestuous. Put in a theme or two, such as the ghostliness of the family: “You see, Baretti, we’re ghosts; we float, not from choice, but, somehow, from circumstance.”

Given such ingredients, the concoction might turn out well or ill; in the event, Mr. Plante produces nothing more edifying than a limp pastiche of Henry James. He starts off badly, referring to “a fine translucent membranous tissue” when he means cellophane. Then he goes from pastiche to pastiche, his relation to James that of mimic to genius. Parts of the book would make an amusing venture as a graduate seminar exercise: Henry and Baretti are wandering in Boston:

Baretti’s voice became subdued, but calculatedly so. “Do please tell me what I must be warned against.”

Henry felt rigidly constrained; for no reason that he could think of, he was beginning to sweat. “I have no idea what you should watch out for. Perhaps nothing less than the entire country.”

“It’s a big place.”

“Oh, very, very big.”

“You’re not altogether for it?” Henry smiled, as a naïvety. “My being for or against it is totally beside the point. It’s an inexhaustible mass. It—“ But he cut himself back from saying any more, aware that he was out of the bounds of what he would in any case allow himself to say.

The elegance is self-regarding, parasitic, like style in drag. The prime effect of Mr. Plante’s novel is that we recall Henry James’s novels, and deplore the fact that at this moment we are not reading them. Samuel Johnson said of Prior that he had everything by purchase, and nothing by gift. Mr. Plante has probably spent much labor and spirit trying to conjure a novel by mimicking a novelist, but what he has produced is not even, by my reckoning, the ghost of a novel. Genius apart, what his book fatally lacks is perception, the passion of perception; if James’s criteria are invoked, Mr. Plante has only himself to blame.

“The essence of moral energy,” James says, “is to survey the whole field.” Of the present fictions, only Herr Böll’s comes up to that mark. It is a commonplace that the contemporary novelist finds the whole field intractable, he cannot survey it, cannot master his experience. He trades upon a single vision. But Heinrich Böll, writing now of one corner of the field, registers the whole field by the amplitude of his care. The effect of his care is to relate the momentary detail to other details which he has not given; his concentration gives an impression of extension and latitude. One experience incriminates another. “Tell me what the artist is,” James says in the Preface to The Portrait of a Lady, “and I will tell you of what he has been conscious.” To write “The Train Was On Time” one would need to have been conscious of many things, and of their intimate relations; of the human sense of history, the mystery of things, feeling, suffering, love, beginning, middle, and end. Conscious, too, of art as a still persistent possibility.

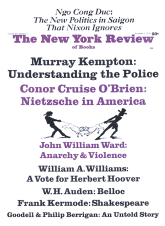

This Issue

November 5, 1970