To the Editors:

Each of those who have signed the above petition undoubtedly has his own estimate of its possibilities and significance. We should like to say something about how the statement came to be prepared and give our own view of its possibilities.

Students and faculty members at the University of Rochester reacted to the news from Cambodia and Kent, Ohio, in the same way as their counterparts elsewhere. At a mass meeting on May 5, it was decided to boycott classes and to use the time to discuss what might be done. (The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences later voted to support this boycott by students.)

When a campaign in support of this petition was first proposed at this meeting most people reacted with a feeling of déjà vu. The proposal seemed trite. But before the discussions were over, most concerned students, including a sizable number of radicals, accepted the petition campaign. They had the support of left-wing faculty members.

The questions raised by skeptical radical students, however, were anything but frivolous, and we should like to review some of the arguments presented by those who decided to support the petition and in fact helped to draft it.

The most striking argument was contained in the observation that we have tried institutional politics and failed. Certainly, the experience of 1968 cannot be recalled with warmth or any sense of great achievement. Since the war has not ended, it could be argued that neither electoral politics nor radical action has worked.

Yet it is our contention that much has worked. The war in Vietnam is a protracted war for us as well as for those more closely involved in it. The forces of national liberation in Asia and elsewhere know, as Nixon knows, and especially as the unlamented LBJ knows, that the peace movement in the United States has significantly narrowed the Administration’s room for maneuver both politically and militarily. Even if we could be certain that all our efforts, perpetually engaged, could not in themselves bring this war to an end, we would retain the duty to press those efforts as a meaningful contribution, whether ultimately small or large, toward the outcome.

But if we grant the need to keep going, what is the point of reopening a struggle on traditional political terrain rather than in the streets? To begin with, it ought to be clear that Nixon’s policy has been one of deliberately provoking disorder, especially on the campuses. Agnew’s ominous attack on Kingman Brewster coincided with the decision to escalate the war. Nixon’s outburst against “bums” on the campus must be read in the same light; the events at Kent State crowned the policy. This policy, if we read it correctly, was designed to make it appear that the opposition to the war is an isolated phenomenon composed of undisciplined middle-class youth—and it is a policy that is now failing.

If the movement can be contained on the campuses, it can be killed on the campuses. If it can be turned into acts of violent frustration of a kind likely to be feared, resented, and certainly misunderstood by the working class and the middle class, then Nixon will surely weather the storm. We believe that there is a Silent Majority in the country—and that it is against the war. But if the resentment and foreboding are to be turned into effective political action, the chasm between the universities, which have been the focus of the antiwar movement, and the community must be bridged. No amount of seized buildings could match the effect of thousands of students and professors going door to door to talk to workers and middle-class Americans. Among other things, face-to-face contact is the best antidote to the fearful and unreasoning reaction of “straight” people to our youth. That reaction has been carefully nurtured by Washington as part of a policy of divide-and-conquer at home.

Undoubtedly, some liberals are ready to leap to support of the petition campaign because they believe it to be a diversionary effort designed to get the students off the campuses and to channel their energies into something harmless. It could of course degenerate into that. But consider the response on the University of Rochester campus alone: on a few hours’ notice some 800 students, out of a student body of not much more than 3,000, collected 8,000 signatures and raised $4,000. At this writing 45,000 signatures have been elicited from the Rochester area alone. One of the accomplishments of the effort was to create the beginnings of a link between campus and community; in the long run, that accomplishment can be consolidated and, if extended across the country, can make a decisive difference.

The frustration that grips our young people, and indeed that touches all of us, has been fed by Nixon’s repeated success in rallying the people to each new adventure. Why should this gambit surprise or dishearten us? When the President of the United States goes before the American people and says that he has a plan to end the war and that he needs support, how should we expect them to respond? Let it be remembered, however, that Lyndon Johnson went down that road, and far more effectively than Nixon, until he fell from power. These support-your-President campaigns have their own rhythm, and therein lies Nixon’s weakness. Each time the President makes this plea, the majority he rallies is smaller or less dedicated and the time span allowed him is perceptibly shortened.

It is essential, therefore, that the pressure be kept on even as the tactics shift. We must avoid the notion that people are convinced once and for all about the nature of the war and must be prepared to go over every argument, again and again and with the greatest patience.

Most of us, for example, are sick of teach-ins and wonder how much more talk we need. But a teach-in at a local church or community organization that had previously been mindlessly pro-war or indifferent is not the same thing as one more teach-in on a campus where the argument has long been exhausted. A simple device like a petition campaign, properly used, can be the vehicle for reaching two kinds of people: those who have supported the war or are wavering and are willing to listen to new analyses, and those who have been or are now convinced and are ready to take some action. Those who consider signing a petition a meaningless or trivial action ought to consider that most Americans have probably never signed a political petition in their lives. For them a decision to do so now—and to contribute a few dollars or even a few cents to support peace candidates—is a decision to take a dramatic first step toward engagement.

But can this kind of political action hold any meaning any more? Even if the petition receives wide support, are we not once more allowing ourselves to be sucked into harmless gestures that the government can and will probably ignore?

This is not a call for one more petition, one more Congressional campaign, one more effort to use institutional political machinery. It is a proposal to use a specific political device in order to intercede in a specific political crisis. Many members of Congress are clearly incensed at Nixon’s policy. The first result of their reaction has been the cry of “constitutional crisis.” Now, clearly, Nixon has not done anything that Truman, Kennedy, Eisenhower, or Johnson did not do before him. But each time the constitutional issue has been fudged, the executive power has been expanded, and the President has been given new powers to pursue predatory policies. That the country is now prepared to review the Presidential power and to concern itself with the question of limiting it can be a major breakthrough and can itself offer new opportunities for popular pressure to restrain, if not defeat, a policy of aggression.

Beyond the constitutional question is the immediate question of staying Nixon’s hand. It is naïve to believe that Congressional censure—in one form or another—would not deeply compromise the President. Even if he were to stare it down and continue on course, an open split with Congress would enormously complicate his plans for building a popular center-right coalition. Lyndon Johnson was brought down under far less painful conditions than Nixon can now be made to face. Popular opinion is by no means impotent, but its effectiveness is considerably limited by its division. Many who oppose the war or are sick of it are frightened by the specter of campus disorder or black revolt. Nixon has obscured the antiwar feeling of his own constituency by a calculated policy of deepening the fear of social disorder. But this strategy would be sorely tried by a general revolt in Congress against his foreign policy.

Unfortunately many congressmen read their constituencies as supporting the President’s policy or at least as opposing its enemies. Everything must be done to demonstrate to them that the path of personal political safety is the path of firm opposition. If it is true that the events in Congress, not in general but at this time and under these conditions, are of major importance to the peace movement, then it follows that everything possible must be done to bring popular pressure to bear in support of a general confrontation of Congress with the President.

Many radicals understandably gag on such a strategy. Our best young militants here at Rochester, for example, heatedly and correctly argued that these measures will not in themselves expose the imperialist basis of American policy and may in fact divert the attention of radicals once more into liberal politics. But there is nothing in this or any reasonable alternative strategy that makes such an outcome inevitable. The hard fact is that the New Left has collapsed and the Left, Old or New, is in disarray. But the work of the 1960s has not been in vain: a far larger portion of our people is attracted by a radical critique of American society than ever before.

Students and faculty at the University of Rochester are combining in workshops and classes, organized in an “Alternate University,” to provide analysis and discussion of community problems. We are determined to use this campaign to build a firm bridge between the university and the community, and so, we understand, are others in universities across the country. The unity and discipline that our students have displayed here have provided hope that a new turn in the fortunes of the Movement can be effected.

Elizabeth Fox Genovese

Eugene D. Genovese

Rochester, New York

The following petition is self-explanatory. It was launched at the University of Rochester by a group now incorporated as the National Petition Committee. It has been endorsed by hundreds of individuals across the country. Faculty members and students on numerous campuses are sponsoring campaigns to collect signatures throughout their communities. The response of working-class, business, and professional people has been extraordinary. The signatures here represent a small sample of adherents.

We need your signature and your financial contribution—fifty cents from people without much money and big bills from people with. Money received will be spent in districts where the election constitutes a referendum on the war and will also be used to sustain a nation-wide organization. A board of directors representing faculty, students, members of the local communities, and figures of national importance is being formed to ensure proper handling of funds. Please send your signature and contribution to:

National Petition Committee

Todd Union, River Campus

University of Rochester

Rochester, New York 14627

Professor Gordon Black

Professor Arthur Goldberg

Department of Political Science

University of Rochester

Co-Chairmen, National Petition Committee

Elizabeth Fox Genovese

Secretary, National Petition Committee

PETITION:

We ask the United States Congress to assert its constitutional powers in matters of war and peace, to condemn our recent invasion of Cambodia, and to require the President to bring our troops home. We wish no further military involvement in Indochina.

The following are among the initial signers and sponsors of the campaign:

Robert Brustein

Eleanor Clark

Martin Duberman

Richard Eberhart

Richard R. Fernandez

John Hope Franklin

Eugene D. Genovese

Paul Goodman

Francine du Plessix Gray

Elizabeth Hardwick

Anthony Hecht

Lillian Hellman

John Hersey

H. Stuart Hughes

Winthrop D. Jordan

Alfred Kazin

Christopher Lasch

Robert Jay Lifton

Robert Lowell

Stewart Meacham

Arthur Miller

Sidney Mintz

Willie Lee Rose

I. F. Stone

William Styron

Robert Penn Warren

Richard Wilbur

Thornton Wilder

C. Vann Woodward

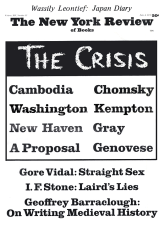

This Issue

June 4, 1970