In response to:

Protest from the December 21, 1967 issue

To the Editors:

In the argument between Robert Bly [NYR, Dec. 21] and Harvey Swados [NYR, Jan. 18] about turning down Federal support because of Vietnam, I think the issue has become blurred by moralizing. There are, of course, moral issues, but each individual must decide uniquely how he is in the world. It is understandable that one, absorbed in honest work, is indifferent about the sponsor; another is satisfied if he is not pressured; another rights the balance by engaging in protests or illegal anti-war activity.

The political problem is a different one: it is how, effectively, to impede and try to stop the juggernaut of the government and our society. This is largely an empirical question, and people in various occupations have special opportunities. To refute Bly, Swados gives a rhetorical list of necessary and innocent jobs that are Federally supported; but indeed these can be sharply differentiated. Thus, just at present, in my opinion, it is not best for Peace Corps and VISTA volunteers to quit; but they ought, by corporate noncooperation and protest, to force a showdown with the administration and Congress, so the Americans realize that they cannot have both the Vietnam war and the darling image of the Peace Corps. There is no sense in poor patients of a hospital quitting, but there is sense in doctors balking when the case gets to be like Captain Levy’s. A student would accomplish little by refusing a scholarship, unless it is in a military area; professors (and students) would accomplish a lot by precipitating a crisis in universities tainted by Federal support—more than 80 percent of money for R and D is military; and professors of natural and social science would be politically effective, and are morally bound, to purge their departments. These are categories mentioned by Swados; we could proceed through other occupations. Factory workers ought certainly to resist the official AFL-CIO support of the war, quitting the union; arms-factory workers ought to quit altogether, hard as that may be.

In the particular topic of controversy, writers and intellectuals who do not immediately sustain the system, their social weight consists primarily in their prestige individually and as a group. Politically it probably doesn’t make much difference if they take grants or not, for I doubt that the Americans care whether or not the government supports the arts or the artists spurn the support. Indeed, a prudent moralist would not even apply for the grant and so could not refuse it, and there would be no newspaper story! But it makes an immense difference, I think, if these people stand by Spock, Raskin, et al., and make our society see that, as it is, it must jail its civilization.

And everything depends, finally, on how desperate the situation is. What if we invade North Vietnam? What if we are verging on atomic war? There is a time—I am sure Swados would agree—when we have to try to stop the works altogether with a general strike. It is a fatal characteristic of our present crisis that we cannot consider moral issues out of this appalling context. Therefore decent people call each other names.

Paul Goodman

New York City

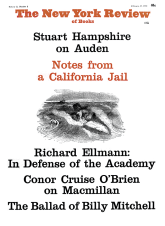

This Issue

February 15, 1968