Buchan has been lucky in his biographer. Like him Janet Adam Smith is the child of a Scots minister. (Her father, who was a distinguished academic, was indicted for heresy by among others Buchan’s father. The indictment failed.) Like him she knows the two Scotlands of post-Jacobite days. There was the democratic, strenuous, puritan tradition, despising English softness and worldliness, which bred tough individualistic men of brains and push who sought their fortune in England, the Empire or America; and there was the other Scotland from which they fled—the mawkish, rhetorical, self-righteous, juicy, unctuous society pilloried in literature from Holy Willie’s Prayer to The House with the Green Shutters. The Scots kept an eye on their bright boys and deflated them if they assimilated too smoothly to English ways; but they were proud that in their poverty-stricken country a man rose by his merits and not by birth. To seek success was part of the national myth. Buchan simply set out to be successful in the classic Scots way.

First move. Educated at a fine Glasgow grammar school, Buchan enters the university there at seventeen. In his first term he goes up to Gilbert Murray at the end of his lecture and asks what Latin translation of Democritus was used by Francis Bacon: He would like to know because he is preparing an edition of Bacon’s Essays. Shrewd. On to Oxford with glowing testimonials from Murray where he keeps himself by his writing as much as by winning prizes and scholarships. The publisher, John Lane, makes him his literary advisor and, already in Who’s Who giving his profession as “undergraduate,” he ends with a First in Greats, many useful upper-class friends and the entrée to great houses and London society. Then off to South Africa after the Boer War to join Milner’s kindergarten of dashing young administrators engaged on the pacification of the country. Having broken into the world of affairs he marries on his return a Grosvenor. Fails to wangle a job under Cromer in Egypt. Friends worried that he won’t declare himself for one or other political party: finally plumps for the Tories. In the First World War becomes director of propaganda. Fails to get a knighthood. Best sellers pour out at the rate of one a year, romances with imperial settings and of secret service doings. Soon he is in Parliament representing the Scottish universities. Becomes an intimate friend of Baldwin and later, in the days of the National Government, of Ramsay MacDonald. Fails to get into the Cabinet or even a ministry. Turns to writing biographies and historical works. Sends sons to Eton. Represents the Sovereign as High Commissioner of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Asked in 1935 to perform in similar style as Governor-General in Canada. Mackenzie King wants him to come as a commoner, but Buchan writes “An immediate peerage might revive Mother.” It revives him. Much liked in Canada, supports appeasement, writes autobiography in which he says: “I never went to school in the conventional sense for a boarding school was beyond the narrow means of my family.” A martyr all his life to an ulcer. Dies of a stroke on eve of his return home in 1940.

The remarkable quality of Janet Adam Smith’s biography is to make the reader see that despite this extraordinary effort to assimiliate himself completely to the ethos of the English Establishment Buchan was an engaging and enlightened man. He remained a loyal Scot and never cut himself off from his family, even when his parents pursued him out to South Africa. His mother was a rich figure of comedy, always eager to take him down a peg and unload her miseries upon him. She used to knit through his speeches in the General Assembly and in a deafening aside regretted that she had not had his adenoids out when he was a child. He provided for her and treated her with resigned affection. He may have been on the make in Oxford but how did he compare, working his way through college every hour carefully planned in either making money, furthering his ambitions or in developing his mind, with the idle rowdies who surrounded him? He did not fawn on every aristocrat. He chose as his friends men who may have been well born, but had ability. He might have found it much easier to enter Parliament as a Liberal before 1914 but his choice of the Tory party was a wise act of prescience. Invariably kind to the young and unimportant, helpful to Scottish poets such as Hugh MacDiarmid or Edwin Muir, friendly towards the Clydeside Labour M.P.S. who were only sad that he seemed to have strayed into the wrong camp, his warm-heartedness was as striking as his efficiency. Janet Adam Smith sets against the anti-Semitic characterization in some of his stories the fact that he himself was a Zionist, friend of Weizmann and an honored supporter of Jewish causes. He foresaw that Britain’s main hope lay in the American alliance and he had no use for the customary British gibes about American culture. As a Conservative he was independent; making an unsparing attack on the politics of Safety First at the very time when the phrase was being used by Baldwin as his election slogan. He was canny but not small-minded; as a boy he had poached salmon and his delight in adventure, simple people, and the unconventional never left him. He stood out against attempts to muzzle the B.B.C., associated with the young thrusters in the party, distrusted the Churchill who wanted to smash the unions during the General Strike, and believed in Baldwin as the architect of industrial peace. His term of office in Canada was of unbroken success because he was not anti-American or a patronizing Englishman but of much the same heritage as thousands of Canadians. He had no illusions about his novels. He wrote to make money and while he knew he could turn out a serviceable yarn, he never bothered to read reviews because he did not see himself as contributing to literature. Why did he not go further? Was it really because he was too nice and insufficiently ruthless, too little in fact of a careerist?

Advertisement

The Establishment—and in particular the inner circle of the Conservative party which is composed of a few leading ministers and a larger number of silent, long-service backbenchers, the Tory knights—is a cold-hearted judge of men. “How do you handicap him?” is the phrase used when they want to sum up a man’s usefulness. The phrase is characteristic of the contempt by politicians for genuine personal relations. Buchan was far abler than many of those who got office, he had wider sympathies, and put into words most effectively the kind of generous imperial vision which many Conservatives imagined inspired them. But Conservatives don’t like literary gents. In wartime they put them in charge of propaganda—Duff Cooper was to follow in Buchan’s footsteps—but in peace they are suspect even when, like Buchan, they flatter them by romanticizing their kind of politics. It was not that he was too liberal for them, or never acquired the House of Commons manner: He simply wasn’t their kind of man. But he could be of use as a front man, and that was what they put him to. When Leo Amery said that Buchan was not really interested in politics, he meant that Buchan had not the talent for the real hard work in Parliament—the pursuit of a line of policy and the determination to convince others that this is the line to follow. Thus when the Tory knights looked at Buchan in the paddock and marked their card, they gave him few marks for toughness and even fewer for the talent of practicing politics and getting what he wanted. Beaverbrook, whose standards of drive in inter-departmental warfare were admittedly high, had noted that Buchan was too gentlemanly in controversies with the Foreign Office in the First World War: and that power behind the throne, Tom Jones, noted that on the Pilgrim Trust, “Hugh Macmillan and James Irvine quickly overpowered Buchan with a stroke or two.” Apprenticeship under Milner was a poor training for British politics. It was colonial administration; little negotiating skill was needed. In Parliament Buchan was not even an influence. His real role was to be that of the confidant and hand-holder of his chief and of his fellow Scot, MacDonald. He made them feel happier.

But there was in him a profounder weakness. The great romantic artists of the nineteenth century discovered new truths about personality and the nature of life. Buchan’s romanticism was a device which enabled him to evade the truth: It was a cocoon of words and ideas which insulated him from the world that intrigued him so greatly. This would have surprised him. His novels are full of characters drawn from life. Richard Hannay was based on Ironside, who rose to be Chief of the Imperial General Staff; Sandy Arbuthnot was a portrait of the improbable Aubrey Herbert and later of the scarcely less probable T. E. Lawrence. But Buchan’s yarns are full of sentences which mean practically nothing. The Kaiser is described as “a human being…who had the power of laying himself alongside other men.” The wicked Medina is “a god from a lost world.” The modern girl is “a crude Artemis but her feet were on the hills.” The villainess, Hilda von Einem—“mad and bad she might be but she was always great.” His villains have to be more than wicked: They have to be the personification of evil, dark forces, masters of diabolic mechanisms. When he described Henry VIII he “hated him for he saw the cunning behind the frank smile, the ruthlessness in the small eyes; but he could not blind himself to his power. Power of Mammon, power of Anti-Christ, power of the Devil maybe, but born to work mightily in the world.” As a result when he had to make up his mind about someone who might be considered as a power of the Devil he decided that Hitler was just “tom-foolery.” Buchan’s trouble was that he could not help looking on the bright side of life. All his friends were most pellucid, luminous swans, all his political colleagues were wise and sensible men. He was thought to be more sophisticated than his other competitors in the thriller game in not painting his villains irremediably black and indicating that even his heroes had dark nights of the soul. But his prose indicates a deep-seated revulsion from attempting to tell the truth. That was why all his generous impulses towards the unemployed and the humble, or his understanding that the English upper-class system of nepotism and loyalty to the boys of the old school at the expense of thrusting Scots pioneers, was vitiated. When he came to the point he could not resist the appeal of ancient titles. “You have no idea of the bores we had to put up with,” said one of his sons, “because their ancestors had fought at Crécy.” His biographer explains that he held the notion that “where once there had been greatness something of it will stay in the blood, and one day the spark will again be fanned into a flame.” Genetics are somewhat more complicated. He understood much of what was fatally wrong in English upper-class rule, as indeed did Baldwin; but just as Baldwin was unable to change it owing to indolence, Buchan was reluctant to act because he was gooey about it. No wonder the Tory knights thought so little of him. They are immune to flattery. Self-flattery is what they like.

Advertisement

BUCHAN would have been surprised to learn that today his books are combed by the writers of theses at universities for evidence on the relation, say, of the novel and imperialism; and he has already been put under the microscope by Richard Usborne in his highly entertaining Clubland Heroes and by Gertrude Himmelfarb in a perceptive essay. Yet there is the suggestion that beneath the fear of sex, the public school ethos, the imperialist view of race and class, the worship of success and denigration of intelligence except as a tool for success, he is not only more serious than other thriller writers, but a kind of Calvinist critic of the Tory-imperialism of his times. No doubt he reflected more upon the meaning of life than Trollope; yet compared with the truthfulness of that limited, unintellectual but honest novelist, who also wrote gentle romances of the upper classes of his time, Buchan is a tissue of verbiage and nonsense. His writing is another milestone in the deep decline of the romantic novel, beginning with Stevenson and Hall Caine and ending in the swamps of the inter-war years best sellers. But it has the value of a documentary: It retails the confused dreams and evasions of a ruling class which was unable to define the problems that were strangling it and of a man who in the end preferred the spectacle of seeing the Crown Princess of Japan “greatly excited by my six pipers going round the table” at the Governor General’s residence to facing the terrible realities of his age.

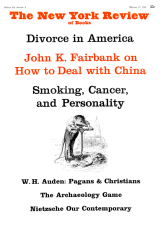

This Issue

February 17, 1966