How bitter must be the wailing of one of those souls lingering beyond Lethe, when Stanley Elkin beckons it to leave Elysium, to return a second time and bear the sluggish body! The shade of Achilles said it was better to be the slave of a poor farmer than to be king of the dead, but Achilles, not having read the stories in Criers and Kibitzers, Kibitzers and Criers, could not have known how miserable life can be in the vision of a really determined author. Perhaps Thersites, the bandy-legged and pin-headed, envious, becuffed, tear-stained, might have understood; but I wonder if even he would have drunk the dark blood willingly just for a chance to live again in one of these nine stories.

Stanley Elkin summons up his nine heroes and then beats them back down, blow by blow, into the dust. That they are revenants adds perhaps some special painfulness to what he does, for we have seen them miserable enough before: Greenspahn the suffering storekeeper, Preminger who goes to Catskill resorts hunting spinsters, Bertie the addicted musician, Feldman whose doctor gave him a year to live, Push the neighborhood bully, Cousin Poor Lesley, Perlmutter…. They have thronged with their sorrows in the Jewish literature of our day. But here Greenspahn must suffer not only the death of his son and the cruel affront to his nerves of the coarse world he lives in; his employees cheat him, his customers cheat him, his companions bait him, he is constipated, he has horrible dreams, and at last he must recognize that his son, “twenty-three years old, wifeless, jobless, sacrificing nothing even in the act of death, leaving the world with his life not started,” was also and gratuitously a thief who stole from his father’s cash-register.

The manner in which Stanley Elkin conducts his characters to their dooms is sprightly. Even the characters themselves are given to making bitter jokes. Greenspahn thinks of his son. “His son was in the ground. Under all that earth. Under all that dirt. In a metal box. Airtight, the funeral director told him. Oh my God, air-tight. Vacuum-sealed. Like a can of coffee.” The addicted musician, bent on destroying himself, destroys the apartment his friends have kindly lent him, with the zeal and dreadful efficiency of the Marx brothers, and with as many jokes. He hits one of his hostess’s paintings with a glass of beer, and observing the beer drip down the leg of a donkey in it, he says, “Action painting.” He wanders through the apartment, through study, kitchen, bedroom, and in each says, “Here’s where all the magic happens.” He experiences hallucinated dialogues which, like his wisecracks, take the form of ironic parodies of bourgeois clichés. Doubtless we are supposed to feel for him some of the pity and terror we feel for William Campbell in Hemingway’s similar and very much shorter story, “A Pursuit Race.” The wit of the man who is destroying himself is supposed to give us a sense of the value the man once might have had. But in Stanley Elkin’s story, surely there would not have been so much of this monologue, in the form of modern patter, unless the author felt that the patter had some value in itself, both as amusement and as an attitude of more than clinical significance. But it is not amusing. Nor does it have much force as a presentation of the beatnik point of view. This same strategy brings to most of Elkin’s stories not a true complication or ambiguity, but rather a species of the evasion into sadism which affects so much of the fiction written today by University Wits. In short jokes, this attitude can be amusing, at the expenses of the predictable queasiness of the audience. Carried on at length, it simply raises the question of why the author is so interested in bedeviling with his witchcraft the poor souls he has conjured up and set into action. It is not fate but the author’s wish that drives these miserable ghosts to their sordid ends, and all the time, he is laughing—or seems to be, he seems to be giving them what he supposes are amusing lines to recite.

But most cruelly of all, Stanley Elkin involves his spirits sometimes in the dread machineries of allegory and fantasy, and here neither he nor they are at home. Poor shades, slip back now into blessed night and the waters of Lethe!

A good witch would not be so cruel to enchanted spirits, as Alison Lurie proves in her novel, The Nowhere City. She transports her Katherine and Paul Cattleman, a young Ivy League academic couple, to Los Angeles, and as she causes them to appear and disappear in various circumstances there, we see that it is a place as crazy as the Wonderful Land of Oz. Not even Steinberg’s marvelous drawings of that region, of its pinnacles and signboards, spike-heels and Jax, its automobiles and its swimming pools, have brought it to life so cleanly and so quickly, so comically. But things in this Oz are not only bright and funny, they are bright and funny in quite unexpected ways: this is not the standard satire of freeway, Forest Lawn, and stucco.

Advertisement

The good witch knows exactly what to do with her captives here. Katherine has sinus attacks and is frigid and doesn’t know she is pretty. Paul is the very definition of square. They see the Nowhere City and the city sees them.

The good witch provides Paul with a beautiful beat waitress, who introduces him to the drop-out life of Venice Beach. For Katherine, she provides an irresistible seducer in the form of Dr. Iz Einsam, psychoanalyst and estranged husband of Glory Green, the movie star.

Since she is a good witch, Alison Lurie forces neither her enchanted city nor her enchanted visitors to do anything their natures do not demand; only, in this Nowhere City, they are driven into unwonted action, they must respond and their responses are at once unexpected, comic, and, in the Land of Oz, logical. The author moves them about very rapidly and precisely, with a strict timetable. Since they are all very young people, they possess or discover enough energy within themselves to keep up with all this. Katherine, the shy Cinderella of the tale, is the one who registers and recognizes the theme behind all the comings-and-goings. If at last it seems a theme for the very young, a single theme to be taken in rapid motion, then neither Cinderella nor the reader will complain, for the final enchantment is to set everyone free of the spell. Only the most delightful comedies can turn us back to their beginnings again this way, liberated.

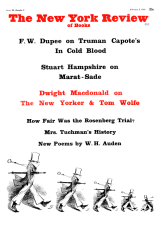

This Issue

February 3, 1966