The final test of our political morality is not our moral posture but our political program and our readiness to discuss and solve political problems. The moral and religious rhetoric of many recent books on the race crisis is not a serious contribution to the critical problem the civil rights movement faces in establishing itself on firm political ground. This is a problem the Negro leadership has failed to resolve. The white liberal, whose major contribution could have been to give the Negroes a political direction, and the white radical whose contribution could have been a heightened political consciousness have been of little help. Delighting in their own moral regeneration through participation in the movement they have virtually betrayed that movement through a failure to develop an adequate program.

Thomas Merton, in “Letters to a White Liberal,” which appears in his book, The Seeds of Destruction, expresses the radical’s delight in his own commitment, without offering either the Negro or the white liberal a political position of any kind. The theme of Seeds of Destruction is that man moves daily closer to Christ and the Christlike life. Whether we are in or outside the church, we are, he believes, subject to the beneficent effect of Christ’s presence working toward our inevitable salvation. Pope John’s Pacem in Terris is, to him a noble document which expresses the Franciscan ideal of peace and rejects the Augustinian concept of the just war. He engages in a good deal of philosophical speculation about Pacem in Terris but never comes to terms with the baffling problems of world politics that must be solved if the objectives of this document are to be fulfilled.

This faith in the inevitable emergence of the good society dedicated to true brotherhood leads Merton into a strange and politically irresponsible position on the civil rights movement. According to him, the Negro embodies in his struggle for equality the ideal of Christian love and the aims of Christ, and he should therefore be supported even at the cost of great personal sacrifice. Indeed, Mr. Merton argues that sacrifice will be necessary because the material interests of white liberals and Negroes are in conflict. The Negro struggle should be supported for the sake of conscience.

But altruism is a risky base on which to form a political alliance. Mr. Merton seems reduced to it because he is unable to envisage a program that will unite the civil rights movement with any other section of the population in an alliance based on self-interest. He writes to James Baldwin that he finds it unfortunate that he is not a Negro himself. To be sure, if the Negro has been singled out by History to fulfill Christ’s promise, then it is unfortunate that History has passed by those of us who are white. The best we can hope for is to live in the reflected glow of the Negro’s historic mission, and support it at great personal cost, lest our self-interest drive us into the arms of conservatives who fear the Negro and want to keep him in his place.

But I am white, and I can support the Negro struggle for an assortment of motives, not the least of which is self-interest. In order to resolve the problems that confront the Negro, American society must provide an adequate material base for its entire population. Among other reasons, I am an ally of the Negro because his material and political security will insure mine. And even if the Negro is motivated by love, and even if society is reduced to the civil war Merton anticipates. I do not believe that I can assume any inevitability about the success of the civil rights struggle.

The Negro is a fragment of a class. His summer victories are eradicated in the winter in the white man’s courts. His demonstrations are expensive and easily absorbed by white society. To argue that it is a service to the civil rights movement to make a blanket attack on the white liberal without dealing with the issues through which the movement might secure to itself allies—and to place one’s faith in success on faith in Christ—seems to me smug utopianism and political obscurantism.

If Mr. Merton derives his political strength from religious Truth, James McBride Dabbs temporizes his with a dash of psychology. Who Speaks for the South? tries to explain what newspapers have documented as a tendency to depravity in the South with vague philosophizing and psychologizing. I wish that I could say that it is Mr. Dabbs who speaks for the South, and he eventually may. But not in this dull and empty book. Mr. Dabbs is a past president of the Southern Regional Conference and, long before the average liberal was enchanted by the civil rights struggle, he emerged as its champion, and at much greater risk to his person and his future than a good many people who have written better books.

Advertisement

It is Mr. Dabbs’s thesis that white southern culture and white southern identity has been determined by the Negro. He understands the white southerner’s brutality as the result of what is probably a unique psychological chain reaction: the southerner is reacting to his guilt which is in turn a reaction to his shame at having enslaved the Negro. According to Mr. Dabbs the white southerner is also a schizophrenic. His religion is individualistic and his culture rooted in a sense of community, and this schism between his faith and his deepest inclinations drives him to irreconcilable conflict.

Insofar as the Negro has broken the southern white’s contact with the earth, he has weakened his religious sense. For in all religious the earth is preeminantly important. The earth itself is feminine, she holds within her womb the seed of life and gives birth to all plants; she nurses animals and men upon her broad bosom. And if the earth itself is not a goddess, it is at least—let us say—a summer home for the gods, who wander here from time to time as men and women. In the Christian view it is more than this; it is the special object of God’s delight, where once his Son came to live, and die, rise again, and where, in the form of the Holy Spirit, he lives until the end of time.

But considering the feminine quality of the southern culture, it might be more accurate to say that the Negro has not caused the white man to lose touch with the earth but has confused and corrupted the touch.

Mr. Dabbs does not believe that the Negro is inherently corrupting. This passage is ripped out of context and I chose it because it is a characteristic example of his style of argument. In his view, the white southerner, having corrupted the Negro, is in turn corrupted by the Negro insofar as the functions to separate the White from the soil. But to attempt to understand the southern mind with this Jeffersonian analysis of culture is a fruitless task. Does the Iowa wheat farmer have a more stable culture than the commercial New Yorker? Is he less corrupt? What of those yeoman farmers who, Mr. Dabbs knows, worked side by side with their Negro slaves over a century ago, and whose descendants, where they are still bound to the soil, comprise the most vicious element in southern white society? What of the white sharecropper and tenant farmer? Does he have an uncorrupted relationship to the Negro?

C. Eric Lincoln’s book, on the other hand, leads me to believe that the southern mind labors under a weight of anxiety, an anxiety that is not the product of guilt but of a long history of Negro struggle. My Face is Black traces this struggle back to the first slave ship whose human cargo rose in revolt, through the carefully organized or carelessly haphazard slave revolts, to the slave mothers who strangled their offspring at birth, to the Negro houseworkers who killed their masters with poison and ground glass, to the white Southerners sleeping armed to the hilt, to massacres of Negro populations in terror of another uprising. The image of a white South determined to preserve white privilege against a Negro population whether overtly or insidiously struggling to assert itself, emerges as a determined expression of conflicting interests, not between a white man and his divided soul, but between two socio-economic groups, one the oppressor, and the other the oppressed. This is not Mr. Lincoln’s argument. It is mine. But his excellent and well-documented section on the history of Negro struggles in the South leaves the reader with no other conclusion. I suspect it is an argument he shares.

Mr. Lincoln is troubled by the Black Muslims and Malcolm X. He feels that they express a deep-seated Negro mood. “Malcolm X,” he says, “is a symbol of the uninvolved leaderless masses whose hatred for the white man has been most often expressed at selfhatred, and whose vast potential for aggression has been displaced upon each other.” I view Malcom X with concern, but not for Mr. Lincoln’s reasons. If the Negroes do move toward a black nationalist position it will not be because they are a leaderless mass, but because the Negro leadership has failed to develop and elucidate a political program which it is prepared to define and defend and has left a political vacuum in the civil rights movement. This makes it possible for any opportunist to make a mess of the movement, and it subjects it to capture by a well-organized and disciplined political faction of any tendency.

Advertisement

But I am not so sure that the Negro masses are as leaderless as Lincoln supposes. If we view the civil rights struggle as emanating primarily from NAACP, CORE, SNNC, and the SCLS then Mr. Lincoln is correct. The Negro masses are leaderless and disoriented. But the civil rights movement has been rooted in the Negro church. As far back as 1937 a share croppers’ strike was organized in Birmingham in a Negro church and by a Negro preacher, and won. The church is to a large degree the Negro’s natural home. His identity and culture are rooted in it, and the Negro church is not leaderless. This is generally recognized to be true in the South, but few appreciate the control the church exercises over its membership in the North and the degree to which it has influenced the civil rights struggle in the North. Although it has not functioned in its own name, it has nevertheless been a prime instrument in bringing out or withholding the personnel to man the demonstrations organized by the civil rights movement. But Mr. Lincoln has little to say about organizing the resentful Negro masses in ways that would make them more effective politically.

Howard Zinn is nothing if not political, and in SNCC—The New Abolitionists he writes about an organization which has been extremely active in organizing protest and registering voters in the South. Yet he gives us no insight into SNNC’s political orientation nor any understanding of its tactics and strategy, or, indeed, its leaders, James Forman, or John Lewis, or Robert Moses. Instead he has written a history of the civil rights movement in the South which he presents as if SNNC were the embodiment of this movement and its logical heir. Nor does the book tell us how SNNC differs as an organization from the rest of the civil rights movement. We are left with the impression that some spontaneous combustion took place in the South and that young Negro students and leaders arose and called themselves SNNC. Mr. Zinn contents himself with writing about the Freedom Rides which were organized by CORE and the lunch counter sit-ins which occurred before SNNC was formed, and finally discussing in detail the tenacity and personal suffering of SNNC members as they attempted to register Negro voters.

His book does, however, make one indispensable contribution. It contains tape-recorded statements made by SNNC workers and supporters who have been drawn into the struggle; these give real understanding of Negro feelings about white society and the motives that lead young civil rights workers to allow themselves to be beaten up in a Southern jail to preserve their personal dignity. He quotes a statement by Charles Wingfield, a sixteen-year-old boy:

I wondered what it was like to live…countless nights I cried myself to sleep…I stayed out of school a lot days because I couldn’t let my mother go to the cotton fields and try and support all of us. I picked cotton and pecans for two cents a pound. I went to the fields six in the morning and worked until seven in the afternoon. When it came to weight up, my heart, body, and bones would be aching, burning, trembling. I stood there and looked the white men right in the eyes while they cheated me, other members of my family, and the rest of the Negroes that were working. There were times when I wanted to speak, but my fearful mother would always tell me to keep silent. The sun was awful hot and the days were long…the cost of survival high. Why I paid it I’ll never know.

The economics of the race crisis have nowhere been more simply or clearly stated.

The relations between SNNC and their former supporters in the civil rights movement have deteriorated. The Council of Federal Organizations is no longer a solid front and Zinn fails to discuss the differences that have separated the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the NAACP from SNNC and CORE, and, more to the point, the differences that have existed between CORE and SNNC. It is my understanding that it is SNNC’s policy to function outside the establishment. They refuse to cooperate in any compromise that looks like a deal. That the remarkable victory at the Democratic convention of the representatives of the Freedom Democratic Party assumed the aspect of a defeat is an expression of a political position that SNNC has taken and which Mr. Zinn does not choose to discuss. He argues instead that SNNC is not political and is free from ideology, that it is radical, but not doctrinaire. I don’t know what that assertion means. It is true that SNCC gave nominal support to the recent successful efforts of the liberal Democratic study group in Congress to deny seniority rights to Representative John Bell Williams of Mississippi and Albert W. Watson of South Carolina who supported Goldwater. But SNNC’s basic program was and is to unseat the Congressional representatives from Mississippi and replace them with Freedom Democrats.

The difference here is not only tactical. It reflects a different commitment. The liberal caucus is engaged in an internal fight to gain control over important committees in Congress. SNNC is engaged in a struggle for representative government in the South. The first is a maneuver within the existing political machinery, the second a frontal attack on the machinery itself. I would have welcomed a discussion of these differences and SNNC’s political program, particularly since it may ultimately prevail in the civil rights movement. Simply to deny that SNNC has a political orientation is not only misleading and dishonest but leaves us incapable of supporting what may in fact be sound. It is also a refusal to allow SNNC’s politics to be examined and perhaps refined by public opinion. To seduce the reader into supporting SNNC by writing what is in fact a history of SNNC’s martyrdom, without giving the reader a chance to evaluate SNNC’s politics and program is a factional maneuver.

There is no question that SNNC’s approach is valid within the context of the struggle in the South. No deals are offered and so none can be made. Any rapprochement with southern institutions would involve a complete abandonment of the struggle and a return to disenfranchisement and social debasement for the Negro. But this is not true in the North, for northern institutions respond to pressure. When the Freedom Democrats refused to accept the deal which would have given them two seats at the Democratic convention, they were rejecting a compromise which was consistent with the pressure the civil rights movement has been able to bring to bear on the labor movement and on white liberals. It is a question whether the selection of Hubert Humphrey as Vice President actually does represent a victory for the labor movement. But two seats at the Democratic convention for a Negro movement in the South is a miracle. And it was a miracle that was wrought by a liberal, labor, and civil rights coalition. It seems to me that it may have been a mistake to thwart such an alliance by rejecting the compromise, especially since SNNC would still have been free to keep its own counsel and to carry on its struggle for genuine enfranchisement of the Negro in the South.

Is there no room for programmatic unity between the civil rights movement and the labor movement? Some Negro leaders, such as Bayard Rustin, believe there is. The Negro struggle in the South threatens to destroy the alliance between the southern bourbon and northern business oligarchies. This is an alliance which is also in the interest of the labor movement to destroy, and although their interests are not always concurrent, they are natural allies in a struggle for jobs, education, and housing. For example, what if the teamsters could be persuaded to honor a Negro picket line? Might that not encourage the AFLCIO to enforce a certain discipline on the locals that represent the workers in the building trades? Need such a discipline threaten the jobs of the white workers in these trades? In New York and New Jersey, for example, 90 per cent of the homes being built are built by non-union labor. A determined organizing campaign among the workers in the building trades could create an integrated union. What if CORE in Detroit had chosen to support the printers’ picket line during the newspaper strike instead of picketing the pickets for their lily-white union? The strike was over automation. A struggle for jobs between the Negro and white worker will lead to equalitarian poverty. So will a struggle for jobs between white workers. The Negro and the white worker have a great deal to gain in supporting each other in a fight against poverty. The white man in Appalachia is not better off than the Negro in Harlem. They have common problems, and as Mr. Keyserling has pointed out the Johnson poverty program solves the problems of neither.

The trade-union movement shrinks constantly under the pressure of automation. It can choose to repeat the recent history of the mineworkers union and continue to speak for a diminishing number of privileged workers who are not thrown on relief, or it can insist on protecting the interests of those workers now threatened by automation and preserve the labor movement. The latter possibility would allow for an integrated work force; the former, continued racial strife.

To be sure, the white urban worker is subject to the same racial bigotry that obtains in society at large, but unity between the civil rights movement and the labor movement might subordinate this bigotry to self-interest and could propel us into Merton’s new society far sooner than moral posturing, religious exhortation, or even SNNC’s desperate and valiant struggle for voter registration. The fact is that the combined efforts of the civil rights movement have succeeded so far in registering about 4000 Negroes in Mississippi, and at an overwhelming cost. At this rate it will take a millenium and countless lives before the southern Negro will be in a position to express himself politically through the ballot. He must find northern allies who will at least force the government to protect his person. Towards this end it may sometimes be necessary to make a deal, for it is almost always futile to rely on good will and the prompting of conscience.

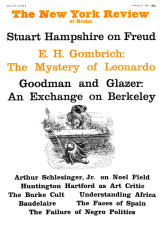

This Issue

February 11, 1965