1.

When I am feeling optimistic about the prospects for literary culture, I imagine a book like the one everybody ran around trying to steal in Neal Stephenson’s 1995 sci-fi novel The Diamond Age. Called a Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer, this “propaedeutic enchiridion” came with its own power pack, a voice-recognition interface, “smart paper” computer pages, “nanoreceptors” to measure the reader’s pulse, and a database that amounted to “a catalogue of the collective unconscious.” Until you could read it on your own, it told you stories in a lovely contralto, even while you slept, about what you dreamed. Designed to grow up alongside feisty four-year-old girls, it encouraged heroic behavior and subversive thinking.

When, on the other hand, I am feeling realistic, the future looks a lot more like Huxley’s Brave New World, full of sex-hormone chewing gum, super-Prozac soma, lots of “feelies,” the occasional orgy-porgy, and a monthly flush of “Violent Passion Surrogate,” where our kidstuffs will be hatched from gene samples, according to a color-coded caste system, and then conditioned at naptime in nightmare dormitories, by “hypnopaedia,” into “elementary class consciousness” and a hatred of botany and books.

The big surprise about Book Business, an elegant cri de coeur fashioned by Jason Epstein from a lecture series he gave at the New York Public Library in October 1999, is its optimism. From Epstein, who has edited books for fifty years—most of those years at Random House before, during, and after its successive sackings by vandals, visigoths, huns, and agents; and most of them downhill for principled publishing in general, from Parnassus to the mall, from Proust, Joyce, Lawrence, and Eliot to How I Lost Weight, Got Rich, Found God, and Changed My Sexual Preference in the Bermuda Triangle—we might have expected weeping-willow lamentations or arrows from a wounded bow.

He’d have earned that right. The manufacture of best sellers instead of literature has to look obscene to someone who was present at the creation, a divine rainmaker, of three different American literary institutions (about which, more in a minute). Someone who, through a golden mist, remembers watching home movies of Thomas Mann after Sunday brunch at Alfred Knopf’s house in Purchase. Someone who recalls W.H. Auden in a torn overcoat and carpet slippers at his publisher in the old Villard mansion on Madison and 50th, with William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, and Dr. Seuss, across the hall from a Cardinal Spellman who actually wrote poems that Random House actually published. Someone who was off-and-on buddies, depending on the thermostatic reading of the dis-tempered times, with the vanished likes of Edmund Wilson and Vladimir Nabokov, lower Bloomsbury bohemians like John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara, and the truculent Partisan Review crowd. And, especially, someone who has seen some of the best minds of his generation, not starving, not hysterical, not naked, but dragging themselves through the first-class seats looking for a stipend from the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Nor does looking on the bright side come with the territory when you realize that some of the best books you published would never have seen the black of ink and the dignity of binding had their sales projections been run by the marketing people who count the beans today at the major houses, where each new book is expected to be by Tom Clancy or Danielle Steel, small printings are a waste of time, unknowns a risky flyer, and still they manage to lose money, because they don’t know what they’re doing. In wry passing, Epstein notes: “When General Electric, a famously well-run company, acquired RCA in 1986, it immediately expelled two divisions that didn’t meet its standard of profitability: a poultry grower and Random House. Twelve years later Advance Publications, the new owner of Random House, came to the same conclusion.” Book publishing “is by nature a cottage industry, decentralized, improvisational, personal,” he reminds us, “best performed by small groups of like-minded people, devoted to their craft, jealous of their autonomy”—like makers of Shaker baskets, Navajo rugs, Amish quilts, jade tigers, or cornhusk dolls: “If money were their primary goal, these people would probably have chosen other careers.”

Certainly Epstein would have. He went into publishing—less “a conventional business” than “a vocation or an amateur sport”—when he realized that his literary standards were so high that “I knew that I could not become a writer equal to my expectations.” To survive and thrive in the warrior cultures of conglomerates like RCA, Newhouse, and Bertelsmann, he had to have been part Talleyrand and part Puck, but certainly not any Mary Poppins: “I am skeptical of progress. My instincts are archaeological. I favor the god Janus, who faces backward and forward at once.” Moreover, “Unlike [my intellectual] friends, I had never been interested in socialism, which presupposes an overoptimistic view of human nature.” So certain is he of the downward slope of the century—Ulysses and The Waste Land “were monuments, to be studied but never surpassed”; Alfred Knopf, in his dark shirt and Cossack mustache, could only be emulated, never “toppled”—that he settles for quoting with approval the Yeats response to Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach”: “Though the great song return no more/There’s keen delight in what we have:/The rattle of pebbles on the shore/Under the receding wave.”

Advertisement

Nevertheless, this is a man who has surfed the Web. And once he’d done so, like Don DeLillo’s Sister Edgar, the jewels rolled out of his eyes and he saw God. Although books as physical objects will not pass away, or bookstores vanish, both will coexist hereafter “with a vast multilingual directory of digitized texts, assembled from a multitude of sources, perhaps ‘tagged’ for easy reference, and distributed electronically.” From this directory, readers will be able to download whatever we want on a Palm Pilot, or transfer materials from a playstation “to machines capable of printing and binding single copies on demand at innumerable remote sites.” Epstein imagines one such location as a kiosk on his corner, and others at the headwaters of the Nile or in the foothills of the Himalayas: “The appropriate technology, in embryo, is already at hand and I have seen it. The future that it implies cannot be evaded. I await it with wonder and trepidation.”

That’s in the preface. He will later describe and admire machinery capable of scanning, digitizing, and storing “virtually any text ever created so that other machines can retrieve this content and reproduce copies on demand instantly anywhere in the world, ei-ther in electronic form, downloaded for a fee into a so-called e-book or similar device, or printed and bound for a few dollars a copy.” Already, machines that print and bind these digitized texts have been deployed by Ingram, a leading books wholesaler, and are on their way to publishers’ warehouses and Barnes and Noble distri-bution centers. Future, less expensive versions are likely to be housed in public libraries, schools, and universities, perhaps post offices, and maybe even Kinko’s and Staples, “allowing readers to bypass retail bookstores completely.” Just insert a credit card to order any text ever written: “Readers in Ulan Bator, Samoa, and Nome will have the same access to books as readers in Berkeley and Cambridge.”

And then there is afflatus:

Dante’s decision seven hundred years ago to write his great poem not in Latin but in what he called the vulgar eloquence—Italian, the language of the people—and the innovation in the following century of printing from movable type are landmarks in the secu-larization of literacy, and the liberalization of society, as well as an affront to the hegemony of priests and tyrants. The impact of today’s emerging technologies promises to be no less revolutionary, perhaps more so. The technology of the printing press enhanced the value of literacy, encouraged widespread learning, and became the sine qua non of modern civilization. New technologies will have an even greater effect, narrowing the notorious gap between the educated rich and the unlettered poor and distributing the benefits as well as the hazards of our civilization to everyone on earth…. That these technologies have emerged just as the publishing industry has fallen into terminal decrepitude is providential, one might even say miraculous.

This is not Epstein the sophisticate, Epstein the epicure, or Epstein the Talleyrand. This is the childlike Jason who would insist on publishing, quite apart from Random House, a Looking Glass Library of nineteenth- and early- twentieth-century children’s books; who wanted to bring back into print such “propaedeutic enchiridions” as E. Nesbit’s Five Children and It.

Only last October, a Times reporter at the Frankfurt Book Fair, stopping by at one of the many booths of the Bertelsmann conglomerate that now owns Random House, spotted a machine “about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle” turning out single-copy hardbacks at a rate of a thousand books an hour, seven dollars each. Practically every issue of TV Guide features a two-page spread advertising Gemstar eBooks—TV Guide’s parent company, RCA, which used to own Random House—with instant access to magazines, newspapers, and best sellers by Patricia Cornwall and Robert Ludlum, plus an interactive dictionary: just plug them in to any phone line. Is the radiant future already upon us? It would be pretty to think so, except for the fact that only 20 percent of the human population has thus far migrated into cyberspace. And 40 percent doesn’t have electricity. And 65 percent has never made a telephone call.

2.

Epstein was already a legend when I arrived in New York in the fall of 1967, as a junior editor at The New York Times Book Review. At the unripe age of twenty-two, fresh out of Columbia in 1949, he had talked Doubleday’s Ken McCormick into underwriting an Anchor line of quality trade paperbacks—the American equivalent of the Penguin Classics series—bringing into accessible being a host of dignified, durable, yet inexpensive editions of the brilliant books that made the modern mind. Titles such as Auerbach’s Mimesis, Baudelaire’s The Mirror of Art, Cassirer’s An Essay on Man, Conrad’s The Secret Agent, Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew, Freud’s The Future of an Illusion, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, Malinowski’s Magic, Science, and Religion, Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, Panofsky’s Meaning in the Visual Arts, and Schrödinger’s What Is Life?, not to mention novels by Colette, Gide, Henry Green, Henry James, Marguerite Yourcenar, and Lady Murasaki, essays by Orwell and plays by Strindberg, George Santayana and Ortega y Gasset, Franz Kafka’s Amerika, D.H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature, and Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station, were all of a sudden available to all of us, for $1.25 or less.

Advertisement

Almost immediately, benefiting everybody, Anchor would have competition from similar lines like Vintage. (Today, of course, the same conglomerate, Random House/Bertelsmann, owns both of them.) These books were what all of us who went to college in the Fifties read, along with The Anchor Review, published by Epstein, where the first big chunk of Lolita appeared between essays by F.W. Dupee and Dwight Macdonald. Long before any of us arrived from the provinces of the sullen South, the happy heartland, or the Left Coast, we had already eaten at Jason’s table.

I should also say that I accepted a salary of $13,000 a year from The New York Times in spite of Epstein’s warning, a year and a half earlier in The New York Review of Books, that this was a fraction of what I would need to live in the Imperial City:

Fifty thousand a year, quite apart from capital, will keep a family, if not in luxury, at least in reasonable comfort and safety. It is possible to manage on less, perhaps on as little as half as much by living on the West Side, doing without this or that and thinking more or less always about getting by. But to fall below this level is to become not a citizen but a victim of New York, incarcerated with thousands or millions of others in those miles of flats in Queens or Brooklyn where the degree to which you must overhear the neighbors’ television is precisely determined by the landlord’s accountant. In New York there are few respectable or comfortable ways of being poor or even middle class. To be without money in New York is usually to be without honor.

It is possible that, in those days, he was less concerned with what they could and couldn’t read at the headwaters of the Nile or Ulan Bator. One might even imagine him, as became a legend most, in a Blackgama mink like Lillian Hellman. But then we were reading him in The New York Review, which Epstein himself had helped to start, along with his wife, Barbara, Robert Silvers, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Robert Lowell, during the New York newspaper strike of 1962, pulling it out of their hat and Lowell’s trust fund like one of Bunny Wilson’s magic tricks. As suddenly as there had been Fear and Trembling for $1.25, there was a fierce alternative to the middlebrow pap in the paper of record. As Hardwick had complained in Harper’s, in an article Silvers edited:

The flat praise and the faint dissension, the minimal style and the light little article, the absence of involvement, passion, character, eccentricity—the lack of the literary tone itself—have made The New York Times Book Review a provincial journal.

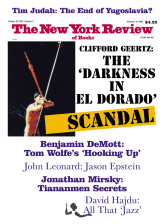

And it was in the pages of The New York Review that we would find Epstein’s prose for the next three decades—from a brief notice, in the inaugural issue, of a new edition of Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, to reviews of books by or about Oscar Wilde, Henry Luce, Tom Wolfe, and his beloved Edmund Wilson, to essays on conservatism, capitalism, socialism, and the economy, Schindler’s List, the conspiracy trials of Bobby Seale and Allen Ginsberg, the CIA and the cold war intellectuals, New York City and Stalingrad, and article after article on our local teachers’ strike of 1968. In these brave articles, supporting an experiment in community control of Brooklyn’s public schools, we met a different Epstein, one who had clearly studied two of his own Random House writers—the Jane Jacobs of The Death and Life of American Cities and the Paul Goodman of Growing Up Absurd—and decided in favor of neighborhoods and participatory democracy, against master builders like Robert Moses and union bullies like Albert Shanker.

But he likes to surprise himself and improve the rest of us. This explains his publishing Norbert Wiener and Norman O. Brown, as well as a Chez Panisse cookbook. Who knew, except Jason? It’s the flipside of a certain loftiness, as when he told The New York Times that Norman Mailer’s Harlot’s Ghost would be a “test for reviewers—one that I fear will find many of them wanting.” This can only be described as preemptive condescension. An early essay on sociology strikes a similar note:

My friends and I [at Columbia] studied literature and not contemporary literature either. That was too unfashionable. It did not repay deep study, nor did American literature. Proust and Joyce, Emerson and Melville were for summer vacation. During the year we concentrated on Dante and Shakespeare and Milton and then, when we were seniors, we were thrust into the modern world through the great rolling surf of Blake and Wordsworth and Goethe and Byron. This is how we first learned of the French Revolution, the vicissitudes of the bourgeoisie and the problem of democracy—through the direct and passionate, if also the wilful and incomplete, record of these writers who, it seemed to us, experienced the emergence of this world most acutely. Only then did we catch sight of Bentham and Mill and still later of Max Weber strenuously casting his nets after abstract fish in waters which seemed to us too shallow to support real life.

3.

The book business in the Fifties and Sixties was better than any grad school. But before we look at Epstein as an editor, and at a publishing world that turned against sensibilities like his own, there is one more prestidigitation to report. He rehearses again the long years it took him to fulfill Edmund Wilson’s dream of a standardized Library of America, our classic literature in uniform editions as “short, plump, and well made” as Wilson himself. (And Epstein, too, for that matter.) It was a war waged over the deadheads of the Modern Language Association, and was only won with the help of the Ford Foundation’s McGeorge Bundy (who may have learned something from Vietnam, after all). From his apprenticeship among direct-mail marketers at Doubleday, Epstein even knew how to sell this library. The black covers with white letters stare down at me now, scattered among Anchor titles with Edward Gorey designs, as if accessorizing. And of course I write these words for a periodical he helped invent. There is much to be grateful for.

About Wilson and Bundy, we get a little gossip. About most of Epstein’s writers, we hear nothing at all. And he has edited a wild bunch—from Auden, Eleanor Clark, and E.L. Doctorow, to Robert Graves, Elizabeth Hardwick, and V.S. Pritchett, to Philip Roth, Stephen Spender, and Gore Vidal, as well as Timothy Garton Ash, Ian Buruma, Oscar Lewis, Norman Mailer, Elaine Pagels, David Remnick, John Richardson, Emma Rothschild, Leonard Schapiro, and Jean Strouse, not to forget the children’s books, cookbooks, a Garden Book Club, and a New Math series. They were why he won a National Book Award in 1988 for distinguished contributions to American letters, and the Curtis Benjamin Award in 1993 for “inventing new kinds of publishing and editing, enriching the world of books.” He had kept some excellent company.

“I believed and still do that the democratic ideal is a permanent and inconclusive Socratic seminar in which we all learn from one another,” he says. Nor was he alone. Many editors and publishers in those years socialized with writers who could contribute to their continuing education. Roger Straus gave luncheons for Nadine Gordimer, Alberto Moravia, and Susan Sontag. George Braziller gave dinner parties where Nathalie Sarraute sat next to Mary McCarthy. You could spend an evening talking to Doris Lessing, John Cheever, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut, and Lauren Bacall, courtesy of Knopf’s Robert Gottlieb. You’d meet Salman Rushdie and Milan Kundera at a sports bar. You were disapproved of by Edmund Wilson, and told by Hannah Arendt: “Young man, we are watching you.” If DeLillo and Pynchon happened to be shy, Grace Paley was always available on the nearest picket line. It was practically impossible to remain provincial.

Book Business makes us want a memoir. We want more about the company he kept, more about the b-school suits and merger maniacs who wrecked it all, and especially more about the friendships that foundered in the Vietnam years and the neocon Ice Age. Both in a chapter here and an essay in The New York Review in 1967, Epstein touches on the CIA, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, and the brains they bought with money laundered through foundation grants. In neither place does he name names. He should have. What may today seem farcical—that an elite band of Ivy League Whiffenpoofs, a Skull and Bones patrician class of covert derring-doers, should have graduated from clandestine wartime service to clandestine peacetime geopoliticking and launch a propaganda counteroffensive against communism, by establishing highbrow journals that toed the Anglo-American line and by subsidizing book publishers, museum programs, art exhibits, youth festivals, and what Arthur Koestler (who had turned a trick or two himself) once mocked as the “international call-girl circuit” of donnish symposia in agreeable spas like Bellagio—was also an early warning of the plague to come; of professional thinkers stampeding to corporate canary cages, cable TV cameras, Op-Ed parking spaces, and the free market where they sell or leverage their skepticism, their intellectual property rights, their first-born children, and their double helix.

Money had always been the way the rest of the culture kept score, while book publishing got along on not much better than an average return of 4 percent on its investment. Was this any way to run a business? Of course not. It was a way to bring out the books they wanted to. Epstein tells us: “Expansion was unavoidable.” But it was only unavoidable if that’s how a publisher kept score, and so went public to rake in the cash, and then had to declare a shareholder dividend each quarter, and so found himself suddenly vulnerable to takeovers by RCA, Disney, Time Warner, CBS/Viacom, Rupert Murdoch, or Si Newhouse. They would all insist eventually on a 15, 20, or 25 percent return on investment. And the way to get it, they imagined, was to stop publishing books that didn’t make serious money and concentrate on brand names, whether the names were writers or, as Epstein notes, “royal princesses, health faddists, reformed mafiosi, discoverers of the twelve secrets of financial or romantic success, Eastern mystics, wrestlers, inspirational football coaches, body builders, diet doctors, gossips, evangelists, basketball stars, and so on.” He could have added serial killers, satanic-ritual therapists, yakshow starlets babbling on about their liposuction, rock musicians addled on cobra venom, war criminals whose mothers never loved them, and survivors of sperm-sucking alien abduction.

Except of course that best sellers are wayward acts of God. Traditionally, book publishers have lived on their backlists. And the way one builds a backlist is by publishing talented writers before and until they find a wider readership and start to sell. Of course, you can go out and buy somebody else’s backlist. But then what will you do with all those titles when you have driven so many independent bookstores out of existence with your discount policies favoring the big chains, and there isn’t any shelf space in the megastores and the mall spaces that you have encouraged to count on a rapid turnover of an insipid inventory of overhyped brand-name commodities in order to amortize their escalating real estate costs, and meanwhile you find that you’ve wildly overpaid millions of dollars in advance of royalties to some disgraced politician or coked-up child molester for a memoir no one will ever want to read even if it actually gets ghostwritten? Here’s what you do. You go to those divisions of your conglomerate that were independent publishers once upon a time themselves before you gobbled them up—those “ghostly imprints of bygone firms” dating back to when literature, issues, and ideas were the priority instead of “sales thresholds,” before decency and common sense were asked to lick the hand of “synergy”—and you tell them to maximize profit by minimizing everything else: cut overhead, trim editorial staff, get rid of the marginal and the midlist, win the lottery.

Epstein says all this, but it seems to me that he lets the idiots off the hook by also blaming agents, adverse market conditions, the internal combustion engine, and the whole idea of suburbs—as if in the suburbs we didn’t grow up reading NAL and Mentor paperbacks about Jake Barnes, Studs Lonigan, and Stephen Dedalus, as if we hadn’t listened to Fats Waller and written polemics against the hydrogen bomb and ended up in libraries and loony bins just like the famous alcoholic and manic-depressive poets in the big cities of the fabled East. Libraries, in fact, he has chosen mostly to ignore, as though part of the problem was not that publishers used to be able to count on a couple of thousand libraries to buy a copy or three of almost any serious new book. And now their ever-receding budgets dissipate into cyberspace instead.

Nor is it the fault of the suburbs that so many newspapers have died in the same go-go greedhead years, likewise incapable of realizing the unrealistic profit margins dictated by their absentee multimedia/entertainment managers. “Expansion was unavoidable.” Then how come it always narrows choices? What a weird metastasis, such expansion. On the other hand, only the culture suffers. Why shouldn’t writers feel the great synergistic pinch as much as downsized air traffic controllers, tugboat captains, steel and garment workers, “adjunct” college professors for whom there will never be tenure, obsolete engineers, and whole battalions of a reserve army of the unemployed mustered out of our tough-love coprosperity sphere by “replacement workers” who line up to scab in every labor dispute, by “temps” who will work without health insurance or pension benefits, and by job flight to Santo Domingo, Jakarta, and Taegu?

But the light at the end of the tunnel is a glowing screen.

4.

Like Epstein, I grew up with movable type. Before it was a job, writing was a passion, and it seized the senses. In high school, I’d jot down an idea, type it up, take it to the print shop, set it on a linotype machine, run off a proof, and publish my own inky self on a flatbed press. This tactile process connected brain and word, muscle and idea, hot lead and cool thought. It was crafty. Ever since, one by one, they have stolen my senses. I was there at the Times when they junked the linotype machines; got rid of typewriters, carbon paper, copyboys, and ashtrays; put up partitions and put down carpets, like a bank. Nowadays, when we don’t write in blue air, copy arrives on disks, to be translated into images, edited into pretend pages, and dream-beamed to New Jersey: no smell, no taste, no feel, no noise. On some ghostly exchange in the information-commodities racket, we are disembodied brokers. So when my wife brought home a Macintosh twelve years ago, I declined to bite the Apple. I thought it would abolish me entirely.

But then one morning, after weeks of refusal, I messed with its icons and I was Jasoned. It was half hypnotherapy, half ecstatic Kabbala. A whole day disappeared while my new chum coaxed me to open and close, to cut and paste, to trash and merge, to change fonts for the glee of it. Until I chose to save and print, everything was provisional, even random, like a doodle, as if I had been introduced to the music of words all over again, and fell once more in love with language, which is why I’d started scribbling in the first place. Suddenly, writing had been reinfantilized. And so at this strange harpsichord I play.

So maybe Epstein’s right. Maybe there will be automatic book-bundlers posted like juke boxes, caffeine machines, and one-armed bandits in every laundromat, gas station, and wedding chapel in the perishing Republic. Maybe all the trade-show book publishers will agree with his idea of a “consortium,” an affiliation of mutual interests, prepared to deposit digitized versions of their entire lists in one big databank “directory” in erotic readiness to download. (Boy, would I like to be a bug in the soup at that summit meeting of bottom-liners and bottom-feeders. While they’re at it, why don’t they fix the Balkans, feed Africa, and internationalize Jerusalem?) Maybe, with a Discover Card and an ATM, we will punch up, spit out, and staple a Ramayana and a Code of Hammurabi.

And while we’re waiting, why not publish ourselves—like Walt Whitman and Charles Dickens, although not like Mark Twain, who went broke trying to do it. Or, in the same fraught interim, we might even get to like reading a long text on a humming scroll, with uplinks to encyclopedic scrimshaw—even though the on-line magazine Slate stopped posting literary essays because no digithead was patient enough to eyeball them all the way through. And perhaps, as even Epstein seems to suggest at the very end of Book Business, we are in store for a metamorphosis not quite yet imaginable—and, “with books no longer imprisoned for life within fixed bindings,” we will learn to fly like Michael Jordan. Or even Mary Poppins.

It is certainly only a matter of time and nanotechnology before we are so wired we’ll need a bar code. Not that Jason worries:

The global village green will not be paradise. It will be undisciplined, polymorphous, and polyglot, as has been our fate and our milieu ever since the divine autocracy showed its muscle by toppling the monolingual Tower of Babel. Over the objections of countless local gods and their vicars, writers have ever since improvised many imperfect towers of their own—clearings in the forest, marketplaces in Athens, catacombs in Rome, graffiti on dungeon walls, samizdat in Siberian camps—and they will do so in the hereafter with unprecedented scope on the World Wide Web. On this point there are strong grounds for optimism. The critical faculty that selects meaning from chaos is part of our instinctual equipment…. Human beings have a genius for finding their way, for creating goods, making orderly markets, distinguishing quality, and assigning value. This faculty can be taken for granted. There is no reason to fear that the awesome diversity of the World Wide Web will overwhelm it. In fact, the Web’s diversity will enlarge these powers, or so one’s experience of humankind permits one to hope.

So I’m thinking about hardware and platforms, software and dots per inch, NuevoMedia’s Rocket eBook, Microsoft ClearType and Softbook Reader. As well as Fatbrain, Versaware, Questia, e-reads, Lightning Source, ibook, iPublish, iUniverse, MightyWords, Mystic-Ink, and AvantGo. Not to mention Hard Shell Word Factory, Online Originals, or Electron Press. And then there are Xlibris, DiskUs, goReader, Cybereditions, Bartleby.com, RCA REB 1200, Franklin eBookMan, Adobe PDF, and Project Gutenberg. If you don’t know which of these is a publisher or a reader or a Web site, I have forgotten, but almost any decent search engine will track them down for you. And if you dig deeper, you are likely to find that the same people own them who own everything else, or soon will, when it all shakes out after the latest market “correction” of the New Economy, because if you think the “military-industrial-entertainment complex” that The X-Files makes so much fun of is going to let you learn something on the cheap, it hasn’t yet occurred to you that the reason marijuana is illegal in this country is because anyone can grow it in a flower box, so where’s the trademark, copyright, patent infringement, or retail markup?

Still, since Epstein is almost always right, I’m trying. But what bothers me is not just that Stephen King couldn’t get his fans to ante up a buck the last time around—thus deep-sixing what had become an extremely interesting serial novel, set in a New York hardcover publishing house that prospers so long as it feeds human flesh to an evil plant, a sort of Aztec geranium—but that Riding the Bullet, King’s highly successful, first-time effort as an e-Dickens, couldn’t be printed at all. It was pre-programmed to disable the print function on our PCs. So much for print on demand. You got to read it once before it vanished, like an urgent message on a Magic Slate. In fact, Simon and Schuster said that they wouldn’t sell the same serial rights to Fatbrain that they sold to Amazon.com and Barnesandnoble.com because Fatbrain lets its customers download twice. In further fact, the word all over the Web is that the standards being written for digital rights management technologies, including the XrML developed by Xerox and endorsed by Microsoft, will allow e-publishers to put time limits on your reading, charge per minute by the page if they want to, and prohibit excerpts. This shouldn’t come as a big surprise if you have recently upgraded your computer, only to discover that as a result you are overnight denied access to anything in the old hard drive, your very own secrets.

Don’t ask me to lend you the last e-book I really liked, because it was only a rental, and they revoked my license anyway.

The other qualm I have is Japan. Just the other day we heard that Japanese bullet-train commuters are all equipped with something like super Palm Pilots on which, if they want to, they can download e-books. Or they can play video games. To the consternation of the Japanese book publishing industry, nobody seems to be reading serious books. Put all your awareness-grabbing eggs in one buzzy little basket, and the Easter Bunny is suddenly illiterate.

Unlike Jason Epstein, I always considered myself a socialist, overoptimistic to a fault, until I had to listen—on a bus, in restaurants, even sitting in Central Park—to what ordinary American citizens actually say to one another on their cell phones. Talk about your hypnopaedia! With respect, I wonder whether the radiant future might not look more like something Rimbaud saw in one of his Illuminations: “It can only be the end of the world, ahead of time.”

This Issue

February 8, 2001