1.

Once there was no limit to the ambitions of museum directors, when it came to the acquisition of works of art removed from the sites for which they had been designed. In 1868, the director of the South Kensington (later the Victoria and Albert) Museum, Sir Henry Cole, wrote a letter from Padua to Sir Henry Austen Layard, the discoverer of Nineveh. “My dear Layard,” the letter begins,

We have been busy all day, alighting on unknown things & new ideas. Here is an idea.

Giotto’s chapel is badly kept & going to ruin. The Custode says it is private property and belongs to the Conte Gradenigo at Venice. If so, why not ask him to sell it & so preserve it? If sold to the State, it will be better kept. If sold to the S.K. museum, it will be best kept. Is this practicable? and worth inquiry?1

The purchase of the Scrovegni or Arena Chapel would indeed have put South Kensington on the map, for it would have netted a large proportion of Giotto’s total surviving oeuvre. Nor was it, perhaps, as totally unrealistic a proposal as one would hope it to have been. Astonishing coups were pulled off in those days.

Only the next year, 1869, the South Kensington Museum was offered the rood screen from the Cathedral of St. John in Hertogenbosch (Bois-le-Duc), in southern Holland. This large Renaissance work, while in no way comparable to the Scrovegni Chapel, was a salient feature of the otherwise Gothic cathedral, but it was said against it that it blocked the congregation’s view of the high altar. The cathedral authorities removed the screen at a cost of 2,000 francs and sold it to a dealer, thereby defraying a mere 60 percent of the costs, 1,200 francs. Clearly they were not in it for the money—the authorities simply hated that rood screen, and put a low value on it. But they were not necessarily typical of their age. For indeed there was an outcry in Holland (too late) which led ultimately to the foundation of the Rijksmonumentenzorg, the state body responsible for the protection of ancient monuments.2

In other words, it was not the case that Holland in this period was devoid of people who put a value on their national heritage. Similarly it was not true of Italy, and Sir Henry Cole could not for a moment have believed it to be true that Italy was devoid of people who valued the works of Giotto. What was indeed the case—and remains the case today, although legislation has completely transformed the situation—was that the conflict had not been resolved between the interests of the private owner of a work of art, or the institutional owner (in the Dutch example, the cathedral authorities), and the nation-state as guardian of the cultural heritage.

The conflict is unresolved because it can never be fully resolved—because it is a conflict. To whom does the ancient silver of an English parish belong? Most assuredly it belongs to the parish. Then is it within the parish’s rights to sell its valuable silver and give the proceeds to the poor, as Christ’s teachings would seem to encourage? Is a cathedral within its rights in selling a screen for scrap (for this practice continued in England well into the twentieth century)? Or a work of art for a large sum? And who owns the Sistine Chapel? Could it be sold off?

The state intervenes against the rights of individual and institutional owners by a set of assertions and definitions. We assert, defensively, that there is such a thing as national heritage. We then define it and/or make an inventory of objects that count as heritage. But our definitions are themselves put under continual stress, and our inventories have to be updated. No doubt many a Belgian, standing in front of James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels, thinks: “This is our national heritage. This should never have been allowed to come to the Getty.” But it takes a long time before a modern work of art becomes accepted as an object of heritage, just as it took time for the idea of heritage itself to be defined and established.

The case of the Gubbio studiolo in the Metropolitan Museum in New York illustrates vividly the difficulties encountered along the way. On the face of it, nothing could have a clearer claim to heritage status. The studiolo is one of three preeminent surviving examples of small, private fifteenth-century rooms that have inlaid (intarsia) paneling, with an illusionistic, perspectival design. The man who commissioned it, Federico da Montefeltro (1422–1482), the Duke of Urbino, is one of the most celebrated rulers of the Renaissance. His portrait by Piero della Francesca hangs in the Uffizi alongside that of his wife, Battista Sforza. The lines Jacob Burckhardt devotes to him—and Burckhardt was no sentimentalist on the subject of princes—delineate the very type of princely honor and benevolent despotism:

Advertisement

Feeling secure in a land where all gained profit or employment from his rule, and where none were beggars, he habitually went unarmed and almost unaccompanied; alone among the princes of his time he ventured to walk in an open park, and to take his meals in an open chamber, while Livy, or in time of fasting some devotional work, was read to him. In the course of the same afternoon he would listen to a lecture on some classical subject, and thence would go to the monastery of the Clarisse and talk of sacred things through the grating with the abbess. In the evening he would overlook the martial exercises of the young people of his Court on the meadow of S. Francesco, known for its magnificent view, and saw to it well that all the feats were done in the most perfect manner.3

And so it goes on. This paragon of the active and contemplative life built many castles and palaces. Urbino, his principal residence, is the setting of Castiglione’s The Courtier, which is set during the rule of Federico’s son. Minor palaces also survive at Gubbio and Urbania (the former town of Casteldurante, well known for its majolica), and have been made into modest art galleries. Visiting these recently, I came upon Federico’s hunting lodge, Il Barco (or Parco) Ducale, just outside Urbania. This strange, imposing structure was converted first into a hunting lodge and later into a rest home, so that a large cupola arises over what would have been the courtyard. Locked and fallen into apparent disuse, it reminds one that Italy has more heritage than it can easily handle—more Montefeltro heritage, indeed, than it can find use for.

In the nineteenth century, the Scottish historian James Dennistoun found the palace of Gubbio (the smallest of the palaces so far mentioned) in a state of neglect, and wrote:

No traveller of taste and intelligence can be otherwise than shocked to find this once chosen sanctuary of Italian refinement and high breeding, the residence in which Castiglione recounted his reception at the Tudor court, and where Fregoso and Bembo were successively bishops, degraded by vile uses and menaced by speedy ruin. It is now in the hands of a person who there manufactures wax candles and silk, but on my second visit in 1843 was closed-up entirely and inaccessible.4

Neglected though it was, the palace had attracted the attention of a local antiquary and an English connoisseur, for Dennistoun quotes detailed descriptions from both of them, and from the latter we learn that the “small cabinet,” that is the studiolo, with its beautiful wooden inlays, “requires little else than cleaning up to restore it to its original state.” Thirty years later, Sir Thomas Graham Jackson visited the Gubbio palace in the hope of seeing the studiolo. The palace, he wrote later, “where the gay courtiers of the Dukes once held their assemblies, is now degraded into a place for breeding

silk-worms. The old shutters still hang from their windows, though ready to drop from their hinges….” As for the cabinet, he sought in vain for any trace of it. Returning to England, he happened to mention his disappointment to Sir Thomas Armstrong, then director of the South Kensington Museum. “Come downstairs,” said Sir Thomas, “and I will show you part of it.”5

In the intervening period, the palace had been picked over. To the horror of visitors such as Thomas Adolphus Trollope (the brother of the more famous novelist) in 1862, the owners of the wax factory were trying to sell off all the finely carved stonework, together with the paneling, which would no doubt have vanished earlier had it not been for the proprietor’s “refusal to sell any part of the spoils of the palace piecemeal.” A decade later, in spite of Italian protests, the gray sandstone doorways and chimney pieces, the inlaid wooden doors and the paneling and ceiling of the studiolo had been dispersed, not, in the first instance, to museums, but to the trade in architectural antiques and to a private collector.

And this brings us to a familiar paradox in the history of taste. What protects a work of art may often be neglect; what destroys it may be admiration. There are two other great interiors of the same type as the Gubbio studiolo: Federico’s other studiolo in Urbino, and the North Sacristy in the Duomo in Florence. What preserved the interior of the sacristy was the disdain that concealed its Renaissance paneling behind Baroque cupboards. What destroyed so much of the interior of the Gubbio palace was the taste for the Renaissance (that taste for which Burckhardt bears much responsibility). At first, as Trollope pointed out, it was only the cost and difficulty of transporting the

Advertisement

stonework which saved it from the dealers. But when Florence was being reconstructed in neo-Renaissance style, it became worthwhile to pay that cost. Florence in those days was much more than an entrepôt for international dealers in art; it was also a place in which palaces and villas were being constructed and renovated in the most prestigious styles of the past.

The pieces that had made up the Gubbio interior were scattered. Some ended up in a Florentine palace, others in a Swiss and a Viennese collection, the Italian consulate in Berlin, the museum in Cleveland, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, which picked up three stone doorways and a wooden door on the Florentine market. But the studiolo itself had made its way to Rome, to the palace of a certain Prince Lancellotti, who intended to reassemble it for his own pleasure. In preparation for this, between 1874 and 1877 the prince had the room, as Olga Raggio puts it in The Gubbio Studiolo and Its Conservation, “skillfully restored” by a cabinetmaker with experience in neo-Renaissance work.

But the scandal of his perfectly legal acquisition pursued him and in 1888 the prince was informed by the police that Italian law “forbade the removal of structural decorations from a national monument.” In fact the palace at Gubbio was not a national monument—it only became designated as such in 1902.

But the prince used another argument with the police: he said that he had bought the paneling in total disrepair, and had restored and enlarged it (since the original space it fitted, as you can see in New York, was irregular). A ministry official, who later became well known as the art historian Adolfo Venturi, was sent to inspect it. He found that “it had indeed been restored and largely renovated so that only a few traces remained of its old parts.”

Neither Raggio nor Antoine Wilmering, in their wonderful study of the studiolo, cares to elaborate on this judgment beyond a tactful remark of Raggio’s, buried in a footnote, that “it seems likely that Prince Lancellotti

had influenced [Venturi’s] negative assessment to some extent.” Was Venturi wrong in his opinion, through inexperience? Was he bribed or otherwise suborned? Or was he right, and are we, in the Met, admiring a masterpiece of the neo-Renaissance cabinetmaker’s skill? Raggio says the studiolo was skillfully restored, and Wilmering, who regrets much that was done to it over the years, concludes that, all things considered, it had survived remarkably well. But the version that suited Prince Lancellotti, even if it made his name mud, was expressed in the guidebook to Gubbio of 1905: the prince had “irremediably ruined it with adaptations and restorations.”6 As long as that version was accepted, the question of the room’s restoration to the palace could be shelved. The paneling itself sat in an attic until the death of the prince, whereupon the grandchildren sold it to a German Jewish dealer, Adolph Loewi, who was shortly to move his business from Venice to the United States. In March 1939, the Gubbio studiolo left Italy for New York. By November of that year,

the Met had acquired it at a knockdown price, and was able to celebrate the acquisition as “a symbol of the spirit of humanistic freedom and a reminder of a happier day in Italy, when the tyrant was a man of science and not just a German puppet in the Teatro dei Piccoli.”

2.

So what is a studiolo? The word can apply both to a room and to a piece of furniture: it is a device for studying in. In the context of a large stone building, whether a monastery or a palace, it provided a small space, which could perhaps be heated, and which, distinctively, offered privacy and a minimum of storage space for books and writing equipment. This characteristic Renaissance contribution to the history of privacy has been traced back to the popes in Avignon, and to Petrarch, whose study still survives. It is linked with the notion of individuality. I was told that in Florence the canons of the Duomo used to hand down their studioli, and that it was considered desirable to inherit the studiolo of a particular cleric known for his learning and his wisdom: some of the odor of sanctity would remain.

In a secular context, to commission or to possess a studiolo was so striking an assertion of one’s education—of one’s continuing cultivation of learning—that it became the practice for the prince or ruler who did so to insist on the most precious elaboration of the design. No doubt many a scholar got by with more mundane equipment (none has survived) but when a prince wanted such a study, he wanted thereby to assert himself symbolically. One feels something of this in the passage from Burckhardt quoted above, which no doubt depends on contemporary sources. The prince, while he eats, is read to from Livy. This marks him down as a ruler forever studying military and political wisdom—his behavior is thus exemplary for the court. The prince listens to a lecture on a classical theme (this part of the day might well be passed in the studiolo).

Thereafter, he might well have listened to the music of a lute or portative organ, since the very small scale of a studiolo made it ideal for intimate music-making. We can tell from an account of the way the household was organized at Urbino that there was a distinction made between the various musicians at court. The singers who performed at vespers or mass, and the musicians who accompanied the duke when out of doors, lived, like most of the courtiers, outside the palace. But two or three singers who performed sotto voce e cum dolceza, softly and sweetly, and who also played the lute, were part of the household.7

Often, when one hears Renaissance music in revival, it is delivered with emphasis and attack, a harsh nasal tone and glottal stops. But when, as it were, Isabella d’Este sang for you, and you were one of an intensely privileged few, sitting across the table from the singer in a tiny room, presumably she would have sung sotto voce e cum dolceza, with absolutely minimum distortion of the face. The same must have been true of these privileged in-house musicians.

The conviviality associated with learned and cultivated company is evoked in a letter from Angelo Poliziano:

At San Miniato yesterday evening we began to read a little Saint Augustine. And this at last turned into making music, leaping up and polishing a certain model of dancing practised here.8

One has to imagine a world in which there was no incongruity in listening to a little Augustine before singing and practicing a step.

The style of grand secular furniture in Italy during the first part of the fifteenth century was Gothic; the wood was carved with tracery details that could well have come straight out of a church. In Justus of Ghent’s double portrait of Federico with his son, Guidobaldo, the duke is reading at a rather high, and seemingly awkward, lectern. The form of the lectern is that of furniture produced half a century before the portrait was painted. The Cloisters Museum has a spectacular credenza (that is, an ornate cupboard on which it was the practice to display the wealth of a family) attributed to the workshop of Arduino da Baiso.

Arduino was one of the famous cabinetmakers of his day, and he executed a studiolo for the then ruler of Lucca, Paolo Guinigi, who kept numerous books in it, and other precious items, including an organ. When Guinigi was overthrown, Leonello d’Este found it worth his while to buy this studiolo and send Arduino himself, with a boy and a horse, to fetch it back to Ferrara, where it was used for many years. This gives an idea of the preciousness of the object, but there is no certainty whether this studiolo consisted of a paneled room or simply a piece or ensemble of furniture. It would have been decorated and made more precious by the use of inlaid woods.

Early in the century, this art of inlay or intarsia became caught up, rather surprisingly, in the main artistic movement of the day. What had begun as an exploitation of geometric border designs with simple illusionistic devices turned into a highly complex display of the perspectival art—the Florentine art of the time, par excellence. The intarsiatore either worked with, or was, one of the leading artists of the day. It was a work of immense labor, which began with the pursuit of woods of rare shades and the gathering and storing of these over a matter of years, before they were seasoned enough to be cut and laid with super-precision.

What sets this kind of work apart from other sorts of virtuosic inlay, such as micromosaic, is the involvement in its execution of artists for whom there was no great shift of category between, say, being an intarsiatore and being an architect. Giuliano da Maiano (in whose workshop the Gothic studiolo was probably made) was both. His brother Benedetto was an intarsiatore, an architect and one of the leading sculptors of his day. Vasari tells a story of him which happens to be both geographically and historically improbable. Encouraged to show his work to Matthias Corvinus, the King of Hungary, Benedetto packs up two chests of immensely complex inlaid work and boards a ship for Hungary. At court he is kindly received, but when he opens up his handiwork he finds that it has been ruined by the water and the exhalations of the sea. “However, putting the work together as well as he was able; he contrived to leave the King well enough satisfied; but in spite of this he took an aversion to that craft and could no longer endure it, through the shame that it had brought upon him.”

Although one cannot see how Benedetto would have gone by sea from Florence to Hungary (and there is no record of him at the court of Matthias Corvinus), the story becomes more plausible if the king in question is the King of Naples. Vasari was aware that the passion for intarsia had passed when it had become obvious that the work was fragile and vulnerable and liable to darken with age. But we also see in the story what was in such work for the artist: it was the very difficulty of execution that would bring him honor.

The fact, then, that a studiolo might be executed in intarsia indicated that it was the very highest grade of prestige project. It was a prestige project, but for a very private place. The duke might sit there alone with his prestige, with all the symbols of his achievement depicted in trompe l’oeil on the walls. When I first visited the studiolo in Urbino, and indeed the one in the Met, I was under the impression that behind these walls, with their illusionistic representations of cupboards with doors ajar, showing books and armor and precious instruments, there must have been real cupboards, where the real contents of a studiolo—the writing instruments, the books, and so forth—would have been kept. But this was never the case. The paneling represented the sort of room the studiolo would have been, had it not had this brilliant paneling.

And the same is true of the North Sacristy in the Duomo, one the greatest, and least known, masterpieces of Quattrocento Florence. The reason why, in the Baroque era, it was fitted out with cupboards was, prosaically enough, because it was a sacristy, and one needs to keep things in such a room. But the artists of the Quattrocento were enchanted with the precision with which they could make the paneling represent the room. Representation on this occasion took precedence over function.

That does not mean that the Duke of Urbino never actually used his two studioli. After all, the sacristy, though slightly impractical and still today modified for the sake of daily use, has been more or less continually functioning for half a millennium. Some rooms are inherently symbolic. A throne room, of the kind that survives in all three Montefeltro palaces, is inescapably symbolic. So is a sacristy: it is a place where the priest prepares himself for the service in which he will face God at the altar. A sacristy is a kind of halfway house between the house of the priest and the holiest part of the church. Access to it is limited. Sacred vestments, reliquaries, the sacrament itself is kept there. It has its own rituals.

Sacristies, as Margaret Haines tells us, were the most comfortable parts of ecclesiastical buildings, with their wooden floors and paneling—places to keep warm in, just like a studiolo.9 And they were places to write in, for wills, marriage contracts, and other such documents were deposited there. A studiolo differs from a sacristy in that a consecrated altar is absent. But there are many other resemblances. Among the symbolism of these rooms are reminders of the cardinal virtues, and the ruler would be encouraged to contemplate his secular duties as well as his great accomplishments. The ruler would know better than to mistake himself for a priest, but he might well feel the analogy between the priest’s preparations before approaching the high altar, and his own private preparations for his public duties. That he enjoyed, that he could command such privacy, set him apart from most of his fellow men, and is a part of the privilege we feel in these beautiful rooms he left behind.

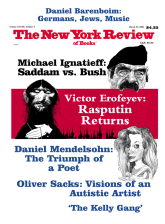

This Issue

March 29, 2001

-

1

Cited in John Fleming, “Art Dealing and the Risorgimento—I,” Burlington Magazine (January 1973), p. 4.

↩ -

2

Charles Avery, “The Rood-Loft from Hertogenbosch,” Victoria and Albert Yearbook, No. 1 (Phaidon, 1969), p. 110.

↩ -

3

The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, Vol. 1 (Harper Torchbooks, 1958), p. 65.

↩ -

4

James Dennistoun, Memoirs of the Dukes of Urbino, Vol. 1 (London: Longman, 1851), p. 163.

↩ -

5

Sir Thomas Graham Jackson, A Holiday in Umbria (London: John Murray, 1917), pp. 195–196.

↩ -

6

See Arduino Colasanti, Gubbio (Bergamo: Italia Artistica, 1905).

↩ -

7

See Ordine et Officij de Casa de lo Illustrissimo Signor Duca de Urbino, edited by Sabine Eiche (Urbino: Accademia Raffaello, 1999) pp. 125–126.

↩ -

8

See Dora Thornton, The Scholar in His Study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy (Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 122, 120; reviewed by me in these pages, August 13, 1998.

↩ -

9

See Margaret Haines, The Sacrestia delle Messe of the Florentine Cathedral, with an introduction by Giuseppe Marchini (Florence: Casa di Risparmio di Firenze, 1983). I am grateful to Dr. Haines for showing me the North Sacristy, which is not normally open to the public.

↩