Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl was first published in 1994—a year after its author, the German novelist Gert Hofmann, died. The translation is by his son, the poet Michael Hofmann, who lives in England and the US and writes in English. You could call it another work of filial piety—along with his translations of Luck and The Film Explainer, the two novels by his father that preceded Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl. All three were written after Gert Hofmann suffered a stroke, which left him unable to read. He dictated them to his wife, and she read the drafts back to him “to correct and embellish aloud.” The pathos of their collaboration seeps into Gert Hofmann’s final novel. Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl is both funny and sad, with a happy but disillusioned and disillusioning ending.

In a mournful afterword, Michael Hofmann gives a brief biography of his father, who was born in 1931 and, according to the publisher, for many years taught at universities in Europe and the US:

My father was always a writer—long before I was born—but circumstances, job, family, moving around—he was an itinerant professor of German lit., with four children—all conspired against his writing. Perhaps he couldn’t see what to do, or what form to do it in. He deliberated. And he wrote plays and a great number of radio plays through the 1960s and 1970s. The result was that when his first prose book was published in 1979…he gave every appearance of being a late starter. Thereafter, he was always a man in a hurry. He didn’t know how long he had left, but he knew it was unlikely to be the 30, 40, 50 years of a standard literary career. He pushed himself. He wrote very nearly a book a year. That’s what presumably gave him a stroke at the age of 57.

Gert Hofmann’s last novel is historical in the sense that almost all the people he writes about really existed—he gives their dates in parentheses. World events, though, play no part. It is a small, intimate, provincial love story reconstructed by Hofmann from letters, contemporary accounts, and most of all from his own imagination. The hero is Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742–1799). A pastor’s son, he was a hunchbacked dwarf who didn’t believe in God and became a professor of science at the University of Göttingen. His particular interest was electricity, and he was highly respected as a teacher. Students came from abroad to attend his lectures—especially from England, where he had been admired and taken up by various grandees when he visited it. His lasting fame, though, depends not on his scientific work but on his aphorisms. They were collected and became a standard German classic, published, republished, and admired—so the publisher tells us—by “Goethe, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Wittgenstein, Tolstoy, Einstein.”

Some of them are profound: “What makes the prospect of Heaven so pleasing to the poor is the thought of equality,” for instance. Others are witty and charming, many are all three, and generally they are much more casual in tone, more intimate, less assertive and authoritative than most published aphorisms. Open The Lichtenberg Reader,* an engaging volume of selections, at page 45, and you get (along with some longer examples): “The critics instruct us to stay close to nature, and authors read this advice; but they always think it safer to stay close to authors who have stayed close to nature.” And, “Everyone admits that the dirty stories we make up ourselves have a far less dangerous effect on us than other people’s do.”

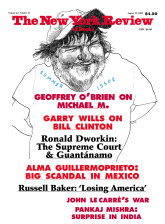

The jacket illustration of Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl is misleading: it shows not a flower girl, but a reproduction of Jean Étienne Liotard’s painting The Chocolate Girl—familiar to regulars (mostly old ladies) of many an old-fashioned German Konditorei, where a reproduction of the girl with a tray of hot chocolate hangs above the little marble-topped tables. But Liotard’s pretty, buxom waitress with an incipient double chin is not at all like the skinny beauty in the novel, who was not quite thirteen when Lichtenberg met her, and—as Hofmann keeps pointing out—whose “breasts were hardly worth mentioning. They hadn’t yet begun.”

The name of the young girl was Maria Dorothea Stechard, and Gert Hofmann called his novel Die kleine Stechardin. He often refers to her as die Stechardin or die kleine Stechardin, and his son explains in his afterword the “beautiful, archaic practice that, along with the definite article, allows a feminine ending, –in, to be appended to the surname.” So he translates her into “the Stechardess”—a word that looks prickly and aggressive on the page and even as if it might be a job description. Perhaps “the little Stechard girl” would have sounded more appealing. Sometimes she is das Kindchen (the little child); Michael Hoffmann turns that into “the girlie” and three pages later even into “the girleen,” although the novel is set in Göttingen, not Dublin.

Advertisement

Altogether, his translation is sometimes eccentric. “Durch das, was er schrieb und zusammenbraute, kannten sie ihn weit über Göttingen hinaus” literally means: “through what he wrote and what he brewed up he was known far beyond Göttingen.” The translation has: “His writings and all-round smorgasbord made him celebrated far beyond the confines of Göttingen.” All-round smorgasbord? Lichtenberg had a laboratory (of sorts, squeezed into his apartment), not a sandwich bar. At other times the translation can be excessively (and a bit unfashionably) colloquial: Lichtenberg is made to reflect, for instance, “about the whole kit and caboodle” when he is simply reflecting on das Ganze—“the whole.”

The Stechardess is gentle, perceptive, giggly, and very beautiful. Lichtenberg is bowled over by her at first sight as she sits on a wall selling flowers. Some English students walking along with him appreciate her too—they are so overwhelmed that one of them bursts into his native language (“God almighty!”) in the middle of the German text in order to give vent to his admiration. To protect her from what such violent appreciation might lead to (Lichtenberg wrote to a clergyman friend), he invited her to come to his house. She refused, but because he explained that he was a university professor, she arrived next day after all, accompanied by her mother.

At the time, Lichtenberg was a frustrated virgin of thirty-five, though he pretended to be only thirty-three. Hofmann makes him vain—pathetically, tragically vain, because of course he was quite aware of the effect of his appearance on others. “Because of his hunchback, he had to be clever the whole time, people expected that of him.” But even though he lived up to their expectations, not least with his aphorisms, they were inclined to treat him with condescension—mostly friendly or compassionate condescension, or both, but still condescension.

At first the Stechardess comes to visit him every day. Then she moves in—into the back of his apartment, he insists, so that no one will catch sight of her. Nevertheless, gossip about the odd couple instantly spreads all over the town. Lichtenberg’s grumpy, slatternly housekeeper moves out, and the Stechardess takes over the household and the cooking. She turns out to be very good at it. Lichtenberg sits with her at meals, and talks to her about his work, which involves a lot of explaining. She doesn’t say much. She is too shy; and it is quite a while before he seduces her, though he has thought about little else since he first saw her. He begins by slowly undressing her:

First he untied her apron, and threw it on the floor. He had never yet undressed a girl, he needed to learn how it was done. But she had never been undressed by a man either, and she didn’t notice how clumsy he was. She thought it had to be like that, and she said again: Oh God! Finally, he had ripped everything open and tossed it on the ground, and he felt her bare skin. He brushed over it, first with his fingertips, then with the whole of his hand.

There are several undressing scenes, and another dubious translation in all of them: a Mieder is not a corset but a bodice—what an eighteenth-century girl would wear over, not under, her chemise. Still, these passages are very tender and touching. Worries about pedophilia don’t come into the heads of any of the characters (including those of Lichtenberg’s friends)—this is the eighteenth century. They don’t seem to worry Gert Hofmann either, and he writes about it in such an innocent, unruffled, uncensorious, radiant way that one can’t help sharing his lovers’ happiness.

The chapter in which Lichtenberg first goes to bed with the Stechardess is a tour de force, in its combination of sexiness, charm, humor, and pathos. Lichtenberg’s desire has to contend with his inexperience, his timidity, and the anguish about his hump; the girl has to overcome her panicky apprehension. But having sex works for both of them. In his ecstasy as they lie together afterward Lichtenberg “had to keep his mouth open, ‘so as not to suffocate for happiness,'” he wrote. Or did he write it? In his foreword, Gert Hofmann says that “many of the things attributed to him in this book have been quite shamelessly invented and concocted…. Under our hands, he becomes not as he was, but as he might also have been.”

Advertisement

The seduction scene comes about halfway through. The rest is an account of the four years of happiness shared by the lovers; for the young girl loves the hunchback as much as he loves her. He teaches her to read. She learns quickly, while he blossoms into ever more colorful silk coats and cravats to disguise his hump. The Stechardess declares it is getting smaller anyway—that it’s almost gone. The story’s blend of domesticity and desire is soaked in Gemütlichkeit. It has hardly any descriptive passages and consists almost entirely of conversation (including the nonstop rumble and clatter of Lichtenberg’s reflections). Michael Hofmann attributes this to his father’s career as a radio playwright. Dialogue was his medium, and when Lichtenberg’s colleagues gossip about him (all of them academics who really existed), their talk is laid out like the dialogue in a play:

Gatterer: Does he still scribble?

Professor Kästner: Yes, in his wastebook!

Schlichtegroll: He says it makes the world more palatable!

Gatterer: With those short legs of his, he’s surely not long for the world?

Professor Kästner: Whenever he stops, it’s so that he can think of something!

Schlichtegroll: Yes, mainly about air!

Gatterer: And don’t forget the weight of the head that’s teetering on top!

Schlichtegroll: His arms go down to his knees! I won’t name the other animal to which that applies!

The idyll with the Stechardess lasts less than five years. Then she catches an infection (it sounds like the plague) and dies. She is only thirty-nine days past her seventeenth birthday, Lichtenberg calculates. His grief as she lies dying is very moving. It shatters him, and after her death he takes to his bed and pulls a pile of imaginary diseases over his head like a duvet. “People began to call him ‘the Columbus of hypochondria.'” He had been quite a hypochondriac before.

But he needs someone to run the household. So he engages another young girl, though not quite as young as the Stechardess. Her name is Margarethe Kellner (1759–1848) and she will bear him

seven, no, eight children. But that’s family history, it goes beyond his own personal story, and he said to himself and already he had written it down…. And then?

Gert Hofmann’s carelessness about the exact number of children is characteristic of his deliberately bumbling, throwaway manner, which is part of his novel’s appeal. As for its last words—“and then?”—that question keeps recurring throughout the story. It is usually asked by the Stechardess when Lichtenberg has finished explaining something to her. Michael Hofmann, in his afterword, hears it as the sound of the

author’s engine, Scheherezade almost, still ticking and willing…. I feel nothing but pride and awe for my father, who put himself through these last three books, and ended Und dann?

This Issue

August 12, 2004

-

*

Translated, edited, and with an introduction by Franz H. Mautner and Henry Hatfield (Beacon, 1959).

↩