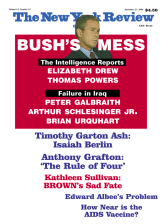

Who got us into this mess anyway—our headlong plunge into preventive war against Iraq? The formal, and facile, answer is George W. Bush. But our president campaigned four years ago on a promise of humility in foreign policy and a rejection of nation-building as social work. Who persuaded him to change his mind?

Democracy in time will demand accountability, though that demand has been muted thus far, and history must one day face the task of explanation. Historians of the Iraq War will have plenty to work with. Unlike the Vietnam War, which crept up on us and was slow in producing a literature, the Iraq War was well trumpeted in advance and has been the subject of volumes of instant history, covering many aspects of the swift victory and the bloody aftermath.

James Mann is the author of two books about Sino-American relations. James Bamford is the author of two books about the National Security Agency. Their ably written new books, Rise of the Vulcans and A Pretext for War, return varying answers to the origins of the theory on which President Bush based the Iraq War—the theory that Iraq presented such an urgent and imminent danger to the United States as to justify preventive war.

The two books nicely complement each other. Mann’s focus is on the State and Defense Departments; Bamford’s is on the intelligence agencies. Vulcans covers rather familiar ground but is better organized, more readable, and more measured in tone. Pretext is awkwardly organized, but it deals with less familiar material and its tone is more outraged.

Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and metalworking, was the sobriquet adopted by George W. Bush’s foreign policy advisers in the 2000 campaign. Mann follows the careers of a gallery of officials whom he calls with justice Bush’s war cabinet: Colin Powell, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Condoleezza Rice, Paul Wolfowitz, and Richard Armitage. Bamford begins with a meticulous reenactment of September 11, then discusses the terrorist war against the West in the 1990s. The final and most interesting section of his book portrays the use and abuse of intelligence by the Bush administration.

Mann and Bamford agree in their skepticism about the neocon fantasy that the establishment of democracy in Iraq will have a domino effect and democratize the whole Islamic world. Mann attributes the visionary delusions of the neocons to the influence of Leo Strauss (1899–1973), the German refugee philosopher who finally found a home in the University of Chicago. Strauss taught his disciples a belief in absolutes, contempt for relativism, and joy in abstract propositions. He approved of Plato’s “noble lies,” disliked much of modern life, and believed that a Straussian elite in government would in time overcome feelings of persecution. Strauss’s teachings can be found in vulgarized form in Allan Bloom’s 1987 best seller, The Closing of the American Mind, a book notable for the total exclusion of the two finest American minds, Emerson and William James.

Strauss’s German windbaggery has had much the same effect on more empirical thinkers that Hegel had on William James (see James’s “On Some Hegelisms”). “Strauss’s influence is surprising,” Mann writes, “because his voluminous, often esoteric, writings say virtually nothing specific about issues of policy, foreign or domestic.” Yet students of Strauss and Bloom—William Kristol, the editor; Robert Kagan, the anti-Europe polemicist; Francis Fukuyama, the “end of history” prophet; Paul Wolf-owitz, the strategic planner—inspired perhaps by the Straussian vision of philosopher-kings, flocked to the Washington of Ronald Reagan, were discontented during the presidency of the elder Bush, and came into their own under the younger Bush.

Anne Norton, a political theorist at the University of Pennsylvania, did graduate work among the Straussians at the University of Chicago. In her well-informed and witty book, Leo Strauss and the Politics of American Empire,1 she lists more than thirty Straussians influential in Washing-ton as of 1999. Given the practice of ideological hiring reminiscent of the Communist Party, there must be more than double that number today scattered among government agencies, military academies, war colleges, and think tanks.

There is a puzzle about the transmutation of traditional conservatives into neoconservative philosopher-kings. “Conservatism reverenced custom and tradition,” Anne Norton writes. Conservatives “distrusted abstract principles, grand theories, utopian projects.” American conservatism used to be Burkean in its respect for the moeurs, for the wisdom embedded in long-established habits and institutions. But the Straussians changed all this. Appeals to history and memory came to seem antiquated. “In their place were the very appeals to universal, abstract principles, the very utopian projects that conservatism once disdained.”

What could be more utopian than the neocon dream that the democratization of Iraq would lead to the democratizion of the Muslim world? “What caused Straussian neoconservatives to abandon an older Anglo-American conservatism for this?” asks Norton.

Advertisement

Perhaps it was the hubris bred by too much power obtained too quickly. Perhaps, like Jefferson faced with the offer of Louisiana, they believed that opportunity should overcome restraint. Perhaps a conservatism bred in the American context to be primarily occupied with domestic matters found itself unmoored when considering foreign policy. Perhaps fear bred fear until the once conservative could no longer distinguish friend and enemy in the fog of an unending war. Perhaps it was the allure of empire.

Perhaps, too, the allure of power? In any case, the old conservatism had been “superseded among the Straussians, by an enthusiasm for empire and a determination to exploit American imperial hegemony.” Empire was evidently not one of Strauss’s preoccupations. “Nothing in Strauss’s writing,” Norton notes, “endorses a Judeo-Christian crusade against Islam.” Marx reputedly said he was not a Marxist, and Strauss was apparently not a Straussian.

James Bamford in A Pretext for War does not mention Leo Strauss at all. Perhaps he did not encounter Straussians in his tour of the intelligence agencies. On the other hand, he has some blunt pages describing pressures brought by the war party in Washington on CIA analysts—for example, a cynical instruction issued at a CIA staff meeting: “If Bush wants to go to war, it’s your job to give him a reason to do so.”

Bamford places considerably more emphasis than Mann does on the role of Israel in getting us into this mess. Mann’s index has only ten references to Israel, covering eleven pages. There are twenty-one references covering thirty-seven pages in Bamford’s index. Defenders of the hard Israeli line seek routinely to silence criticism of Ariel Sharon and Likud by accusing critics of anti-Semitism. But surely the American identification with Sharon’s Israel is a major cause of Arab hatred of the United States, even though Arab governments have not demonstrated much sympathy themselves for the Palestinians. Bamford and Norton confront the Israel question frankly and without a trace of anti-Semitism.

Norton has a chapter, “Athens and Jerusalem,” in which she discusses the post–September 11 strategic plan of Paul Wolfowitz as

built conceptually and geographically around the centrality of Israel…. This strategy could be understood as advancing American interests and security only if one saw those as identical to the interests and security of the state of Israel.

An appealing argument can be made that the United States has an obligation to defend a democratic nation against undemocratic forces. But among the Straussians, Norton writes, “Israel is often admired the more for its less than democratic qualities. Israel has the toughness that America lacks.”

Bamford throws particular light on the mystery of Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency. Mossad has long had an exalted reputation, and its eye has long been concentrated on Iraq. In 1981 Israeli planes, presumably guided by Mossad, destroyed an Iraqi nuclear reactor. Mossad had the strongest motives to continue monitoring and penetrating the government of Saddam Hussein and far greater opportunities to do so than the CIA or European intelligence organizations. Yet on the question of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, Mossad was apparently quite as ill-informed as the CIA. Or was it? That is the mystery.

Bamford has dug up a document, “The War in Iraq: An Intelligence Failure?,” written in November 2003 by General Shlomo Brom, former head of the Israeli General Staff’s Strategic Planning Division. Israeli intelligence, according to the document, “had not received any information regarding weapons of mass destruction and surface-to-surface missiles for nearly eight years.” Brom also charged, Bamford writes,

that despite the fact that Israeli intelligence, like that of the United States, had no evidence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, the Israeli government, along with the media, deliberately hyped the dangers of Iraq before the war.

Yossi Sarid, a prominent member of the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, said that Mossad knew that Iraq had no WMD stockpiles but didn’t inform the US government because it wanted the war to proceed and did not wish “to spoil President Bush’s scenario.” Bamford goes further. He suggests that Mossad and Ranaan Gissin, “Sharon’s top aide,” rivaled Ahmed Chalabi in sending Washington phony intelligence designed to frighten President Bush.

The deceit apparently practiced on the US government by the Likud regime in Israel is pertinent to the imperial dreams, and delusions, of the Straussians. The neocon vision is that the United States as the supreme military superpower is bound to work its will on the rest of the world. Comparisons are often made to the Roman Empire and to the nineteenth-century British and French Empires. Is the so-called American Empire a fitting successor? The neocons expect it will be, and Niall Ferguson, the economic historian, author of Colossus: The Price of America’s Empire2 and admirer of liberal empires, summons reluctant Americans to rise to their historic responsibility.

Advertisement

But Americans, unlike the Romans, the British, and the French, are not colonizers of remote and exotic places. We peopled North America’s vacant spaces, as the white invaders deemed them, from sea to shining sea, but we did not send away our youngest sons to man the outposts of empire. Britain created a British world in India and Africa, as the French did in equatorial Africa and Indochina. But Americans, as James Bryce wrote in 1888, “have none of the earth-hunger which burns in the great nations of Europe.”

Some of our political leaders did. Jefferson said that the United States “ought, at the first possible opportunity, to take Cuba.” John Quincy Adams agreed, considering the annexation of Cuba “indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself.” Adams wanted and expected Canada, too. These things, so authoritatively predicted, never came to pass. The United States has not annexed Cuba or Canada. There is no likelihood that we ever will. The Americans wanted to control their own westward drive but, unlike the British and French, could not have cared less about empire.

Nor are they much interested in empire today. “The term ’empire,'” writes Professor C. John Ikenberry, summing up the common understanding, “refers to the political control by a dominant country of the domestic and foreign policies of weaker countries.” Rome, London, Paris, despite slow and awkward lines of communication, really ruled their empires. Today communication is instantaneous; but despite the speed of contact, Washington, far from ruling an empire in the old sense, has become the virtual prisoner of its client states.

This was the case notably with South Vietnam in the 1960s, and it has been the case ever since with Israel. Governments in Saigon forty years ago and in Tel Aviv today have been sure that the United States, for internal political reasons, would not apply the ultimate sanction by withdrawing support. They therefore defied American commands and demands with relative impunity.

Pakistan, Taiwan, Egypt, South Korea, and the Philippines are similarly unimpressed, evasive, or defiant. For all our vast military strength, we cannot get our Latin American neighbors, or even the tiny Caribbean islands, to do our bidding. Americans are simply not competent imperial-ists, as we are demonstrating in Iraq in 2004. The so-called American Empire is in fact a feeble imitation of the Roman, British, and French Empires.

The neocons, with their imperial dreams, might take a look at Emmanuel Todd’s After the Empire: The Breakdown of the American Order. It is not an anti-American rant by an aggrieved French intellectual. Todd has a formula by which, through an analysis of demographic and economic factors, he accurately predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union in his first book, La Chute Finale. This was in 1976 when the neocons’ Committee on the Present Danger and the CIA’s Team B were predicting that the Soviet Union would very likely win the arms race.

In his new book Todd applies a similar formula to the United States. He may underrate the resilience of the American economy, but in a not unsympathetic way he raises intelligent and disturbing questions about the American future. Regarding the Iraq War, Todd writes, “The real America is too weak to take on anyone except military midgets…such outdated remains of a bygone era as North Korea, Cuba, and Iraq.” Even war against a pathetic Iraqi opponent seems to have strained our military manpower to the limit. Todd concludes, “If [the US] stubbornly decides to continue showing off its supreme power, it will only end up exposing to the world its powerlessness.”

None of these authors mentions an issue that erupted after their books were written. The disclosures about the torture practiced by US soldiers have intensified the awareness of the mess in Iraq and deepened perspectives on the meaning of the war. Torture escaped the attention of the allegedly intrepid American press and television. We now know that there was considerable debate behind the scenes, with memoranda flowing back and forth among the Departments of Defense and Justice and the White House about stretching the ban on torture to permit coercive techniques of interrogation.

This seemed plausible because George Bush and Tony Blair, as “sincere deceivers” in The Economist’s phrase, had honestly believed the tall tales about WMDs. They must have radiated the impression that if interrogators only tried hard enough, they could extract the WMD hiding places from detainees at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. This view must have percolated down the ranks. Hence the appalling episodes that have disgraced the United States and made our talk about human rights appear arrant hypocrisy in the eyes of the world.

At first the Bush administration tried the “bad apples” defense. It was all the fault of a few vicious soldiers acting on their own. In due course a pattern of torture in widespread locations began to emerge. The revelations by the Red Cross and in US reports of systematic abuse undermined the “bad apples” defense; nor did the military act promptly to halt the abuses and punish the abusers. There is an obvious need for a full-scale congressional investigation.

There are at least three reasons that the US should not be involved with torture. The first is that the Geneva Conventions protect American GIs who fall into enemy hands. Terrorists of course do not observe the Conventions, but the revelations about Abu Ghraib fatally weaken our case against terrorism throughout the world and expose the men and women in our armed forces to being tortured themselves. The second is that information extracted by torture is often worthless. Tortured people will say anything that stops the torture. A third reason is that the abuse of captives brutalizes their captors; the heart of darkness can be corrupting and it is contagious.

The press and television in effect set the agenda for public opinion. They were reluctant to add to the low esteem in which they are held by questioning the presidential war. This reluctance aborted the national debate that should have taken place over changing the basis of our foreign policy from containment and deterrence to preventive war, and then over the waging of such a war against Iraq. The press seems to have spontaneously decided that they would not give equal time to skeptics about the war. “Administration assertions were on the front page,” said Thomas Ricks, The Washington Post’s Pentagon correspondent. “Things that challenged the administration were on A18 on Sunday or A24 on Monday.”3 Alarmist utterances by Cheney and Rumsfeld, now proven to be wrong, commanded the headlines and front pages; well-reasoned speeches by Senators Byrd and Kennedy opposing the rush to preventive war—which, on factual grounds have proven correct—were lucky to make page 18. Philanthropists had to pay the press to carry the texts of antiwar speeches.

The 9/11 Commission under Governor Thomas Kean blames Congress for failing to exercise its constitutional role of oversight. But surely the blame must be shared with the supine press. In the March–April Columbia Journalism Review, Chris Mooney reports on the views of the six leading editorial pages—The New York Times, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, USA Today, Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times—from February 5, 2003, when Colin Powell gave his United Nations speech, to March 19, when President Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq. The New York Times questioned the factual case for the war. But no paper, except the Los Angeles Times, seemed to notice or care about President Bush’s fundamental shift to preventive war as the basis of US foreign policy.

For all the mordant questions The New York Times’s editorial page raises about the war, its news columns still play down criticism of the Bush foreign policy. On June 16 of this year a group calling itself Diplomats and Military Commanders for Change held a press conference. Twenty-seven retired professional diplomats and officers condemned the Bush policy and called for regime change in Washington. The signers included Admiral William Crowe, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and ambassador to London; Arthur Hartman and Jack Matlock, former ambassadors to the Soviet Union; Donald McHenry, former ambassador to the United Nations; Stansfield Turner, former CIA director under Jimmy Carter; and other experienced and distinguished figures. The statement by professionals criticizing the government in wartime seems unprecedented in American history and ought to be taken with the utmost seriousness. But the Times, the fabled newspaper of record, ignored the press conference, did not run the statement or quote from it, and did not print the list of signatories.

The Times’s downplay of criticism of the Bush administration continues. On August 4, the Times buried in its National Briefing column an item about a “group,” unnamed and unidentified but said to include twelve former presidents of the American Bar Association and several former judges. The group had criticized Bush administration lawyers for memoranda in favor of permitting torture of prisoners in certain circumstances. Bush’s lawyers, the statement said, had failed to meet their professional obligations by counseling individuals to ignore the law and offering arguments to minimize their exposure to punishment for doing so. This would seem a major story, but the Times was too busy giving prominent play to the so-called Swift Boat Veterans for Truth and their attack on John Kerry’s military record in Vietnam.

When Dana Priest, The Washington Post’s national security reporter, addressed an audience of intelligence officers recently, she was “peppered with questions. ‘Why didn’t the Post do a more aggressive job? Why didn’t the Post ask more questions? Why didn’t the Post dig harder?'” It never occurred to the deferential American press to ask about torture before the Abu Ghraib disclosures, to inquire into the behind-the-scenes arguments about how far to go in interrogation, to inquire much about the treatment of prisoners in Guantánamo.4 This was a big issue in Britain, where there is now a London play about the Guantánamo prisoners, which opened in New York as well on August 26. Guantánamo itself was played down in the American press. The actress Vanessa Redgrave organized a committee of families of British detainees and led a delegation to Washington in March 2004. Their press conference was ignored by American newspapers and television.

Revelations about Abu Ghraib and Supreme Court decisions rebuking our imperial president have led the American media belatedly to try to recover their integrity and do what a free press ought to do for the general welfare. But they are still too much accustomed to their acquiescent ways. For example, the Bush administration is preparing to launch a new program to make nuclear weapons, a policy that a vigilant American press has failed to bring before the public. The situation is as follows. In 1994 Congress passed the Spratt-Purse amendment stipulating that “it shall be the policy of the United States not to conduct research and development which could lead to the production by the United States of a new low-yield nuclear weapon.” Low-yield nuclear weapons, fondly known as mini-nukes, are defined as under five kilotons.

The Bush administration, fearful that evil states might hide WMDs in hardened bunkers buried deep in the ground, called for a low-yield nuclear weapon known in the patois of the Pentagon as a Robust Nuclear Earth penetrator, a description often abbreviated into Bunker Buster. Mini-nukes of course can be used additionally as tactical weapons for the battlefield. In May 2003, the Senate Armed Services Committee voted for repeal of the prohibition on mini-nuke research. Senators Dianne Feinstein of California and Ted Kennedy then submitted an amendment restoring the original language of the Spratt-Purse amendment.

Supporters of the Feinstein-Kennedy amendment pointed out that mini-nukes were not toys, that five kilotons represented one third of the explosive power of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, that the activation of mini-nuke research would run counter to US anti-proliferation policy and would “release a chain of reactions across the world in nuclear testing” (Kennedy), and that there was “no such thing as a ‘usable nuclear weapon'” (Feinstein). Nevertheless the Senate tabled the Feinstein-Kennedy amendment. The fight was resumed on June 3 and 15, 2004. Kennedy made a powerful statement:

America should not launch a new nuclear arms race…. Even as we try to persuade North Korea to pull back from the brink—even as we try to persuade Iran to end its nuclear weapons program, even as we urge the nations of the former Soviet Union to secure their nuclear materials and arsenals from terrorists—the Bush administration now wants to escalate the nuclear threat.

The director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, speaking before the Council on Foreign Relations, compared the US to “some who have continued to dangle a cigarette from their mouth and tell everybody else not to smoke.”

The Senate defeated the Feinstein-Kennedy initiative by a vote of fifty-five to forty. How many readers of The New York Review of Books recall editorials condemning the Senate’s action or news stories about the vote? Yet reopening the nuclear door at a time when preventive war became part of US doctrine may have the gravest possible consequences for the human race.

James Mann, in an afterword to his excellent book recently published in the Financial Times,5 writes that his Vulcans have reached the end of their road. The Bush doctrine of preventive war has been put back on the shelf; the “axis of evil” is fading away; the vision of the Vulcans that America could spread its influence and ideals through reliance on military power is bankrupt. “These days, the Bush administration’s intellectual efforts are devoted not to coming up with new ideas for the future but to devising after-the-fact justifications for its intervention in Iraq.”

Most observers regard the Bush Doctrine as dead. President Bush does not, as he made clear in the unre-pentant speeches he delivered in June at the Air Force Academy and in July in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. “We must confront serious dangers,” he said, “before they fully materialize.” But how many nations is he likely to assemble in his next “coalition of the willing”?

Never in American history has the United States been so unpopular abroad, regarded with so much hostility, so distrusted, feared, hated. Even before Abu Ghraib, Margaret Tutwiler, a veteran Republican who was in charge of public diplomacy at the State Department, testifying before a House appropriations subcommittee in February 2004, declared that America’s standing abroad had deteriorated to such a degree that “it will take years of hard, focused work” to repair it. After Abu Ghraib, it may take decades.

The hard work of repair would surely be speeded up if there were a regime change in Washington in November.

This Issue

September 23, 2004

-

1

Yale University Press, to be published in October.

↩ -

2

Penguin, 2004; reviewed in these pages by Paul Kennedy, June 10, 2004.

↩ -

3

Due credit should be given to The Washington Post for the confessional article on August 12 by Howard Kurtz from which the Ricks quotation and the later quotation from Dana Priest are taken—this in spite of the editorials page’s “creeping hawkishness” as noted by that old Reaganite James P. Pinkerton in Salon on August 8. “The neoconservative voice of the Post’s editorial page,” Pinkerton writes, “is one of President Bush’s most valuable allies.”

↩ -

4

For an exception, see the article “In Guantánamo” by Joseph Lelyveld in these pages, November 7, 2002.

↩ -

5

July 8, 2004.

↩