She knew the story of her family, its future, and her own future within it. Her royal father, Minos, had told it to her. Besides, of late, brief visions of that future had flashed before her eyes. Dreams or revelations? She wasn’t sure. The knowledge of the future made her sad, proud, and ashamed. Her sister Phaedra and she, both suicides, hanged by their own hands! Minotaur, her half-brother, slain! The Athenian ship with Theseus on board was sailing for Crete. Knowing that disaster would strike very soon made her distraught. One late sunlit afternoon she went to the courtyard where she knew she would find her father reclining on his couch of gold and silver, knelt by his side, wept, and told him her fears. She knew he would console her. The King listened, stroked her hair, and said, Be brave, my Ariadne. What is to come is ever before the eyes of Zeus and cannot change. He reveals to us who are his children as much of the future as we can bear to perceive. But not even he can bend the laws of Necessity. The past lives in the minds of mortals. What will come to pass is not what they will know or remember.

Why is that, Father? Ariadne asked. How can that which has happened be undone? My beloved child, Minos answered, the past is only what the poets tell us. Born liars all, like the ones who sing for their supper at my banquet table. Brains and memory addled; for each event that was they will, in each generation, invent ten that weren’t, and each generation will add its numberless inventions. Much later, men even more inconsequential, called historians, will keep rewriting the past until fables take its place.

Ariadne thought hard. She said, Father, you have shown me the way. For us mortals the future is brief; the past may be eternal. To save my honor, I will make my own story of the misfortunes that are to befall me. Here is how it shall be told:

I, Ariadne, knew that the Athenian ship with black sails would once again bring to you, Father, Athens’s yearly tribute—seven youths and seven virgins of great beauty—destined to sate my half-brother Minotaur’s hunger for human flesh and slake his thirst for human blood. I also knew that the hero Theseus, son of the King of Athens, was among them, vowing to kill Minotaur. Revenge moved him, and loathing of Minotaur’s nature, part human and part animal, and for the coupling of which he was the fruit, when Queen Pasiphaë, my mother, maddened by Poseidon, let the sea god’s bull cover her. Concealed in a wooden cow that Daedalus had made for her, she crouched and gave herself to him. Later, you had Daedalus build the Labyrinth where, ashamed, you keep Minotaur hidden. And I knew the prophecy made to Theseus, that I would conceive a passion for him so strong that it would make me betray my country and my half-brother. With my help, he would enter the Labyrinth, surprise Minotaur, and slaughter the monster with a man’s beautiful face and a bull’s body, using a sword smuggled by me. Then, guided by my advice and using a ball of string given by me, he would escape from the maze, and set sail for home with his companions and me as his concubine. This will not come to pass!

I will, alas, give myself to Theseus. But, to humiliate me and recall the bull and Pasiphaë’s shame, the fool will take me doggie-style. The insult will enrage me, and rekindle my love for Minotaur, as man and bull. You know that I honor all living creatures equally. For sex, though, I’ll take the bull anytime. Warned by me, Minotaur will devour Theseus and the thirteen other Athenians. Then, bellowing happily, a garland of roses around his neck, he will ask for my hand, which you will graciously bestow. And so, after Zeus has called you to his side, Minotaur and I and our children will reign over rich and fertile Crete until the tenth generation.

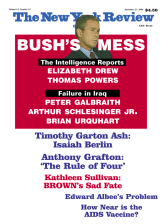

This Issue

September 23, 2004