In response to:

How Bush Really Won from the January 13, 2005 issue

To the Editors:

Mark Danner’s “How Bush Really Won” [NYR, January 13] is easily the best explanation I have seen. His conversations with Florida voters gave unusual depth to his analysis, and prompt these observations of my own.

The majority that the Bush-Rove campaign mustered came from the center of the middle class. By my calculation, their median family income was a quite modest $60,725, yet still enough to live respectably in middle America. In rallying for Bush and Cheney, they were also acclaiming themselves. Indeed, the campaign had told them that they were special citizens deserving special recognition.

The choice to support Bush—and Republicans generally—gives quite average Americans a chance to feel superior. On moral terrain, they show singular virtue by not doing such things that will lead them to resort to abortion. They can take pride in their heterosexuality, regarding gays as immorally self-indulgent. And the time and energy they devote to worship shows their dedication and discipline. Finally, they see nothing wrong with periodic wars (Swift Boaters were an ex-post defense of Vietnam) since fighting marshals character and courage, whereas doubting conveys an aroma of cowardice.

They are also fiscally superior. While most are far from wealthy, these voters tend to live in areas where living costs are not sky-high, and their salaries cover pleasures like trips to Disneyland and Caribbean cruises. Most have enough health coverage, do not feel their jobs are endan-gered, and aren’t yet worried about their retirement. In short, they can differentiate—and distance—themselves from all those “losers” that Democratic candidates ask us to worry about. Hence they feel able to disdain the word “liberal,” since that connotes handouts for complainers who don’t show the energy to make it on their own.

So the Bush candidacy was framed to make a majority by giving some 60 million people a chance to feel good about themselves.

Andrew Hacker

Professor of Political Science

Queens College

New York City

To the Editors:

Convincingly debunking the “moral values” storyline concerning the fall election, Mark Danner suggests that Bush’s victory turned instead on the fears raised by terrorism and the war in Iraq. The Republicans, he argues, constructed a narrative that relentlessly contrasted Bush’s presumed “forthrightness, decisiveness, and strength” with Kerry’s “uncertainty, hesitation, [and] vacillation.” But how, one must ask, did that story work so well as to effectively override the plain facts—the nonexistence of WMDs in Iraq, for example, and the disconnect between Iraq and September 11—which Danner cites? The answer, I would propose, lies at the level of theme and subtext.

The Republican storyline reached Americans at the gut level because it was fundamentally about masculinity—about who is and who is not a “real man.”

The masculine-feminine binary virtually defined the Republican campaign. Bush played the tough, aggressive “stand-up guy” who would “stay the course” because “sometimes a man’s gotta be a man.” Kerry, meanwhile, was transformed into a soft, flip-flopping, effete elitist—a “girly man,” in the immortal words of the Hollywood action hero now governing California, or, in Jon Stewart’s satirical synopsis, “a pussy.” In the Republican narrative, in short, “Democrat” translated as “weak” and “liberal” as “effeminate.”

This is neither new nor surprising. The Republicans have regularly played the masculinity card in recent elections, particularly when bloodthirsty Russian bears or Islamic wolves are sighted in the woods. And the story, as Danner suggests, has often trumped the facts. How else did a combat-averse Yale Yankee morph into a plain-spoken Texas sheriff ridding the Wild West—read the Middle East—of bad guys? And how was a decorated combat veteran so readily converted into a “girly man”? Perhaps it is time for the Democrats to challenge the Republican story directly instead of implicitly endorsing it by (pathetically) forcing their candidates to play with the symbolic toys—tanks, guns, motorcycles—of “real men.”

Paul Cohen

Professor of History

Lawrence University

Appleton, Wisconsin

Mark Danner replies:

“Issues don’t win elections, constituencies do.” As this political chestnut suggests, issues serve politicians mainly as a way for them to consolidate constituencies—and “make a majority,” as Andrew Hacker puts it. Nonetheless intellectuals—amateur or professional, and pundits first among them—like nothing better than to talk about issues and to debate the facts out of which they are built. That Mr. Bush’s reelection seems to fly so dramatically in the face of these so-called “plain facts”—the fact that the stated reasons for the Iraq war have been thoroughly and publicly disproved; the fact that his tax cuts have overwhelmingly benefited the well-to-do at the expense of those in the middle class—drives intellectuals to distraction.

Shortly after the election, an e-mail circulated widely purporting to show that people in the pro-Bush “red states” simply had lower IQs than people in the “blue states.” That the chart was soon shown to be fabricated does not change the widely held conviction among Democrats that those who voted for Bush could only have done so because they were not as intelligent as those who voted against him.

Advertisement

As I tried to show in my article, and as the writers of these letters make clear, this election had, like most, more to do with emotions and attitudes than it had to do with facts. Andrew Hacker artfully describes the Bush campaign’s success in creating a majority of “quite average Americans” who were offered, in supporting Bush and the “values” he stood for, “a chance to feel superior.” On “issues” like abortion, health care, gay marriage, and the Iraq war, among many others, the Bush campaign did not appeal to voters’ “policy preferences.” Instead, as I tried to show and as Mr. Hacker makes vividly clear, the campaign worked to create a “community of attitudes” that privileged self-sufficiency, independence, and self-reliance—in short, the typically “masculine” values on the side of the “masculine-feminine binary” that, as Mr. Cohen points out, Republicans have played on in their campaigns for many years.

The added element this year was a strong ratcheting up of fear—the fear of attack, the fear of vulnerability in the post–September 11 world. Fear bolstered the need for the qualities that Bush was made to represent; fear was the question, as it were, to which Mr. Bush’s clarity, forthrightness, and strength were posed as the answer. Kerry, for his part, was made “the anti-Bush,” exemplifying in his flip-flopping and shilly-shallying everything that Bush stood against—and everything that, if allowed into the White House, could put the country at greater risk. Voters should support Bush not only because casting a ballot for him reaffirmed the values they shared with him and thus, in Mr. Hacker’s terms, made them “feel superior” but because that vote would help keep the threat Kerry was made to represent—one of self-indulgent, indecisive, “feminized” weakness—out of the White House. (To take one example: Bush’s opposition to gay marriage—and Kerry’s implied “softness” on the issue—seems to have been particularly important in bolstering the President’s support among older men, whose votes were, as Scott Turow has pointed out, critical to his reelection.)

That this “masculine-feminine binary” has played a central role in how Americans talk about politics and “issues” has hardly escaped notice; the linguist George Lakoff, for one, has written extensively on it, notably in his book Moral Politics. Still, if emphasizing and reinforcing these attitudes was central to the campaign, why was the subject not discussed prominently in the press? Why did these questions largely remain, as Mr. Cohen puts it, at “the level of theme and subtext”? And why didn’t Democrats “challenge the Republican story directly” as Mr. Cohen urges them to do?

The answer to this, in my view, has to do at least in part with the peculiar kind of “horse-race coverage” that has come to dominate American political campaigns. In the major newspapers and, above all, on the television networks, campaign coverage is typically led by “inside stories” about “campaign strategy.” Articles often rely on unnamed “campaign strategists” who are quoted explaining what is “really going on” within the campaign. More often than not, this is a charade: the supposed “inside story” is just another version of the “message” that the campaign wants to get out to the public, another way of manipulating the news by creating a narrative that in fact helps reinforce the plotline designed and chosen by the campaign in the first place. Far from telling readers and viewers what is “really” happening in the campaign, the “inside story” stratagem is simply another way to get across the carefully crafted plotline developed by the campaign itself.

On March 5, for example, The New York Times published a piece headlined “Bush Campaigns Amid a Furor over Ads,” about a supposed controversy over the campaign’s first television ads, which offered a glimpse of a dead fireman being carried out of the World Trade Center site. In the article the Times reporters revealed that the campaign was “scrambling to counter criticism that his first television commercials crassly politicized the tragedy of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.” Indeed, the controversy was so serious, according to the Times, that it had “complicated efforts by Republicans to seize the initiative after months in which Mr. Bush has often been on the defensive.” Newsweek, for its part, in an article headlined “A ‘Shocking’ Stumble,” reported that the ad controversy “threw campaign officials on the defensive—and raised questions about the Bush team’s ability to effectively spend its massive $150 million war chest, some GOP insiders say.”

Advertisement

Seven months later, and two weeks after the election, Newsweek published another and very different “inside account,” this one based on exclusive access to the campaigns which was granted on the understanding that nothing from this reporting would be published until after the election.* Here is what Newsweek’s writers now told us about what “two Bush strategists” really thought of their campaign’s “shocking stumble”:

McKinnon and Dowd were ecstatic. At a strategy meeting the next day—the same morning the Times headline appeared—they joked about how they could fan the flames. Controversy sells, they said. It meant lots of “free media”; the ads were shown over and over again on news shows, particularly on cable TV. The “visual” of the rubble at the World Trade Center was a powerful reminder of the nation’s darkest hour—and Bush’s finest, when he climbed on the rock pile with a bullhorn. What’s more, the story eclipsed some grim economic news….

At that Saturday’s Breakfast Club, they were still laughing about the ad flap…. Dowd told the group they had received $6 million to $7 million worth of free ad coverage. “Unfortunately, we’ve been talking about 9/11 and our ads for five days,” Dowd deadpanned at a senior staff meeting. “We’re going to try to pivot back to the economy as soon as we can.”

There were chuckles all around.

So much for the “inside story.” As so often in journalism, the source offered the reporter access and the scoop; in exchange, the reporter in effect granted the source—in this case, the Bush strategist—the power to shape the storyline. The reporter thus publishes a supposed “inside story” about “scrambling” within the campaign that is in effect a kind of “false bottom” constructed by the campaign itself and intended to “fan the flames” of what is in fact a largely bogus story. The deeper reality—in this case, the determination to focus relentlessly on September 11 and the President’s “leadership” role in it (“the nation’s darkest hour and Bush’s finest”) and thus to emphasize the “masculine” values of steadiness, forthrightness, and strength that this role exemplified—may have been plain to those political professionals who were looking closely but it was much less clear to voters relying on the press for the supposed “inside story” of the campaign. The Bush campaign’s “shocking stumble” was, in Daniel Boorstin’s term, a “pseudo-event”; indeed, our political campaigns are built largely of such pseudo-events and rely fundamentally on the press and the commentariat to play their necessary part in constructing them and conveying them to the public. Both sides are immersed in this language, of course, and it is hard to see, given the terms of the game, how Democrats could “challenge the Republican story directly”—or even what “directly,” in this context, might actually mean.

All of which means the careful construction of attitudes that Hacker and Cohen describe, which formed the election campaign’s true “inside story,” generally fell outside the mainstream narrative put forward in the press. The public, offered the impression that they are being given a pathway into the inner sanctum, in fact is simply offered another constructed story carefully designed to reinforce the kind of attitudes campaign strategists have decided, in the real “behind the scenes” meetings, are critical to their candidate’s success. What the public gets is mostly mummery and play-acting, and—for 51 percent of them at least—the chance to feel superior.

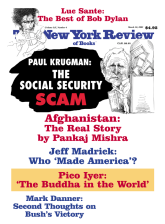

This Issue

March 10, 2005

-

*

See “How Bush Did It: The Untold Story of an Epic Election,” Newsweek, November 15, 2004, p. 61. See also Evan Thomas and the Staff of Newsweek, Election 2004: How Bush/Cheney ’04 Won and What You Can Expect in the Future (PublicAffairs, 2005), pp. 45–46.

↩