1.

It was June 13, 1971, when The New York Times began publishing long articles on, and excerpts from, what came to be known as the Pentagon Papers: a secret history of the Vietnam War, prepared in the Pentagon. The uproar occasioned by the publication is dim and distant now; even among those who remember it, many probably think the whole episode did not matter much in the end. But it mattered a lot.

Presidential power was one thing affected by the publication and the controversy that followed. President Nixon saw what the Times and then other newspapers did as a challenge to his authority. In an affidavit in 1975 he said the Pentagon Papers were “no skin off my back”—because they stopped their history in 1968, before he took office. But, he said, “the way I saw it was that far more important than who the Pentagon Papers reflected on, as to how we got into Vietnam, was the office of the Presidency of the United States….”

Nixon ordered his lawyers to go to court to stop the Times from continuing to publish its Pentagon Papers series. Then, angry because J. Edgar Hoover was less than enthusiastic about acting against possible sources of the leaked documents, especially Daniel Ellsberg, Nixon created the White House unit known as the Plumbers. They arranged a break-in at the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to get his records. (They also discussed, but did not carry out, the idea of fire-bombing the Brookings Institution in Washington and sending in agents dressed as firemen to look for connections to the leak.) The lawlessness of the Plumbers, and the presidential state of mind they reflected, led to Watergate and Nixon’s resignation in 1974. One lesson of those years was seen to be that presidents are not above the law.

Public disclosure of the Pentagon Papers challenged the core of a president’s power: his role in foreign and national security affairs. Throughout the cold war, until well into the Vietnam era, virtually all of the public had been content to let presidents—of both parties—make that policy. As the Vietnam War ground on, cruelly and fruitlessly, dissent became significant. The Pentagon Papers showed us that there had all along been dissent inside the government. Thomas Powers, in an essay in Inside the Pentagon Papers, says that their disclosure “broke a kind of spell in this country, a notion that the people and the government had to always be in consensus on all the major [foreign policy] issues.”

The courts were another institution changed by the Pentagon Papers. Judges tend to defer to executive officials on issues of national security, explaining that they themselves lack necessary expertise. But here, in a case involving thousands of pages of top secret documents, they said no to hyperbolic government claims of damage that would be done if the newspapers were allowed to go on publishing—soldiers’ lives lost, alliances damaged. The government’s request for an injunction against publication was turned down by a federal trial judge in New York, by a trial judge and the Court of Appeals in Washington in the Washington Post case, and finally by the Supreme Court. Floyd Abrams, one of the assisting lawyers who went on from the Times case to become a leading First Amendment lawyer, has said that “the enduring lesson of the Pentagon Papers case…is the need for the greatest caution and dubiety by the judiciary in accepting representations by the government as to the likelihood of harm.”

The press was also profoundly affected by the Pentagon Papers. In the Washington of the 1950s and 1960s, correspondents and columnists shared the government’s premises on the great issues of foreign policy, notably the cold war. The press believed in the good faith of officials and their superior knowledge. The Vietnam War undermined both those beliefs. The young correspondents in the field, David Halberstam and the rest, knew more about what was happening and reported it more honestly than generals and presidents. But would an establishment newspaper like the Times go so far as to publish thousands of pages from top secret documents about the war?

Professors Harold Edgar and Benno Schmidt Jr. of the Columbia Law School wrote that publication of the papers symbolized

the passing of an era in which newsmen could be counted upon to work within reasonably well understood boundaries in disclosing information that politicians deemed sensitive.

There had been, they said, a “symbiotic relationship between politicians and the press.” But

The New York Times, by publishing the papers…demonstrated that much of the press was no longer willing to be merely an occasionally critical associate devoted to common aims, but intended to become an adversary threatening to discredit not only political dogma but also the motives of the nation’s leaders.

Thirty years on, do we need another book about the Pentagon Papers? We do. The issues raised by the 1971 publication and its aftermath—presidential power, the role of the courts and the press, government secrecy—are all still with us. And this book throws fresh and important light on the issues. John Prados and Margaret Porter call themselves its editors, because they include comments from participants in the events. But they really are authors also, providing a running account and analysis that goes beyond what has been written before.

Advertisement

They begin with a description, much of it new, at least to me, and fascinating, of how the papers were prepared in the Pentagon. In 1967 Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, by then beginning to have doubts about the war, told one of his military assistants, Lieutenant Colonel Robert G. Gard, that he wanted “a thorough study done of the background of the Vietnam War.” Gard brought in a former Senate staff member with a Harvard Ph.D., Leslie H. Gelb, as director of the project. The idea at first was to put together a collection of documents on the war. Gelb added a series of studies on what the documents meant. McNamara wanted answers to hard questions: Are we lying about the number of the enemy killed? Can we win the war? To do the studies, Gelb hired experts: some from within the Pentagon, including military officers, and some from the RAND Corporation and other outside institutions. Each wrote about a period in the war’s history.

Prados and Porter include contributions from a number of the study’s authors in their book. An especially interesting one is by Melvin Gurtov, who came from RAND and did the study on the years from the end of World War II and the French return to Indochina to the Geneva Conference of 1954, at which Vietnam was partitioned. He offers some general conclusions he draws from the Pentagon Papers.

“The crux of these documents,” Gurtov writes,

was what they revealed about the duplicity of US leaders, who consistently lied to the American people, the Congress, and the press about many aspects of the war in the Kennedy and Johnson years. Presidents and their national security advisers knew the war was being lost, knew their Vietnamese opponents had popular support while their allies in Saigon did not, and knew that military firepower was no substitute for political legitimacy. But they told the American people the opposite.

Gurtov also praises Daniel Ellsberg for getting the papers to the public. It was “an act of great courage,” Gurtov says, to which I would add, one for which Ellsberg paid a heavy price in right-wing attacks unaffected by the realities of the losing war in Vietnam.

A second section of Inside the Pentagon Papers considers what happened inside The New York Times. Neil Sheehan of its Washington bureau, who had been one of the remarkable young correspondents in Vietnam, got the Pentagon Papers from Daniel Ellsberg. Altogether there were forty-seven volumes: four thousand pages of documents and three thousand of the accompanying studies. But Ellsberg withheld four volumes on peace negotiations; neither the Times nor any other newspaper ever had those. In the forty-three volumes there was a thread: the United States had consistently professed support for a unified, independent Vietnam but just as consistently aided France in opposing Vietnamese independence, sabotaged the Geneva agreement for national elections, and so on.

Sheehan spent two weeks in a Washington hotel reading the papers before, on April 20, describing them to the managing editor of the Times, A.M. Rosenthal. Sheehan and other reporters were then secretly installed in a suite in the New York Hilton, with a guard at the door, to prepare for possible publication. But whether the Times would publish was still an open question. The reporters and editors who were in on the secret all pressed for publication. That included Rosenthal, even though Hedrick Smith, another Times reporter involved in the project, says in this book that Rosenthal personally favored the Vietnam War; journalism was what mattered. But some executives of the paper were opposed; and so was the law firm that had long represented the Times, Lord, Day & Lord. (Details of the debate inside the Times were first published in Sanford Ungar’s 1972 book, The Papers and the Papers.)

The Times Washington bureau chief, Max Frankel, frustrated by the lawyers’ respect for secrecy stamps, wrote a memorandum arguing persuasively that military, diplomatic, and political reporting always used “secret” material. The memorandum was later filed as an affidavit in the court case. On the other hand, it was not customary for the Times to use material from such an enormous breach of classification rules, related to a war that was still going on. That was what gave the Times’s publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, a former US Marine, pause. But in the end he decided in favor of publication.

Advertisement

On the evening of the second day of publication, June 14, Attorney General John N. Mitchell sent a telegram to the Times saying that the Pentagon Papers series violated a criminal statute, the Espionage Act. He asked the Times to stop—and to “return…these documents to the Department of Defense.” Again there was conflict inside the Times about whether to comply. Sulzberger was in London on a long-planned trip; reached there, he ordered publication to continue. A five-column headline in the Times on Tuesday morning said, “Mitchell seeks to Halt Series on Vietnam But Times Refuses.” According to Ungar, Rosenthal said later, “If the headline had been ‘Justice Department Asks End to Vietnam Series and Times Concedes,’ I think it would have changed the history of the newspaper business.”

James Reston, the Washington columnist and former executive editor, was the most respected figure on the paper. His position on the Pentagon Papers shows how things had changed. Reston had had many scoops as a reporter, but he had customarily worked with officials. He knew about U-2 flights over the Soviet Union for years but wrote nothing about them until one of the planes was downed in 1960. Now he pressed for publication of the Vietnam series. If the Times did not publish, he said at one meeting, he would publish the Pentagon Papers in the Vineyard Gazette, the Martha’s Vineyard weekly that he owned.

A similar debate took place inside The Washington Post when it got much of the Pentagon Papers material after the Times was enjoined from continuing to publish. The editors wanted to go with the story. Financial executives, especially concerned because the Post was about to put its stock on the public market for the first time, were opposed. Katharine Graham, the publisher, made the decision to publish.

Don Oberdorfer, a longtime Post foreign and diplomatic correspondent, contributes his recollections to this book. The decision to publish, he concludes, made the Post a newspaper to be taken seriously by the informed. It made it easy for the Post to go with the Watergate stories a year later. All told, Oberdorfer says, the Pentagon Papers had a signal effect on the press. It was the moment at which newspapers “became independent of the government on the war.”

Why were editors and publishers who had worked with presidents on national security disclosures—the Times holding off, for example, on its knowledge of the Cuban missile crisis—now not telling officials what they had? Why had the Times gone so far to keep its secret from the government that it had its reporters working in a guarded hotel suite? The Vietnam War is a large part of the answer. But I also think the lack of trust in Richard Nixon and his people mattered. Would the Times and the Post have done the same if John F. Kennedy had been president?

2.

Next, Prados and Porter describe what went on in the White House. Some of the material has been disclosed before, but it is wonderful to have the quotations from President Nixon and his aides gathered here in all their morbid splendor.

On the morning of the first day, June 13, Nixon told his chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, that the administration should keep clear of the Times series—which after all focused on previous administrations. But shortly after noon, Alexander Haig, his deputy national security adviser, telephoned to give Nixon the latest Vietnam casualty figures. Then he spoke of the “Goddamn New York Times exposé of the most highly classified documents of the war.” It was, he said, “a devastating security breach.” In mid-afternoon Henry Kissinger, the national security adviser, telephoned. He discussed several important matters, including the Vietnam peace negotiations in Paris. Nixon raised the Times story. Kissinger at first said it would “if anything…help us a little bit, because this is a gold mine of showing how the previous administration got us in there” and “pins it all on Kennedy and Johnson.” But Nixon, evidently reflecting Haig’s comment, said that the “bastards that put it out” had done something “treasonable.” Kissinger reversed himself. “It’s treasonable,” he said, “there’s no question.”

By the next day Kissinger was in a rage about the Pentagon Papers. He told Charles Colson, according to Colson’s memoir:

There can be no foreign policy in this government, no foreign policy, I tell you. We might just as well turn it all over to the Soviets and get it over with. These leaks are slowly and systematically destroying us.”

According to Haldeman’s memoir, Kissinger told him that Daniel Ellsberg “had weird sexual habits, used drugs, and enjoyed helicopter flights in which he would take potshots at the Vietnamese below.” Haldeman reckoned that Kissinger was trying to ward off attacks from Nixon because he knew Ellsberg, and Nixon already suspected Kissinger’s staff as a source of leaks. Nixon suspected Kissinger as well. In a taped conversation with Haldeman on June 14, Nixon said, “Henry talked to that damn Jew Frankel all the time.”

In his memoir The White House Years, Kissinger says his strong reaction against the Times series was based on fear that it would upset the approach to China, which was being negotiated at that time, with his secret trip to Beijing to follow. “Our nightmare at that moment,” he writes, “was that Peking might conclude our government was too unsteady, too harassed, and too insecure to be a useful partner. The massive hemorrhage of state secrets was bound to raise doubts about our reliability in the minds of other governments, friend and foe, and indeed about the stability of our political system.” (There is no evidence that Mao Zedong cared about the Pentagon Papers.)

John Ehrlichman, second only to Haldeman among Nixon’s assistants, thought Kissinger was responsible for Nixon’s decision to act against the Times. “Without Henry’s stimulus…, Ehrlichman said, “the President and the rest of us might have concluded that the Papers were Lyndon Johnson’s problem, not ours.”

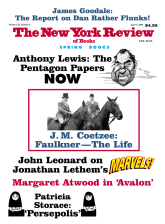

Next came the legal battle. Lord, Day & Lord advised that the government would bring a criminal prosecution. Indeed, its lawyers refused to look at what the Times had lest they be prosecuted under the Espionage Act. But the Times’s general counsel, James Goodale, an early and strong advocate of publication, said correctly that what the paper had to expect, and fear, was an injunction to stop publication. That this was the government’s strategy was made clear by an assistant attorney general, Robert Mardian, in a telephone call to the Times that Monday evening, June 13. Goodale telephoned Lord, Day & Lord to have a lawyer in court the next morning. But its senior partner, Herbert Brownell Jr., said the firm would not represent the Times. He gave as a reason that, as attorney general in the Eisenhower administration, he had written the basic executive order on classification—an explanation that convinced no one. Goodale, in a comment in this book, says that Attorney General Mitchell had telephoned Brownell and told him in effect that it would not be good for the Republican Party if he took part in the case.

Goodale then turned to Professor Alexander M. Bickel of the Yale Law School, reaching him about midnight. Bickel agreed to argue for the Times and was at the federal courthouse in Foley Square the next morning. By lot—the spinning of a wheel by the court clerk—the case was assigned to a new judge, Murray Gurfein, in his first day on the job. That evening Attorney General Mitchell told Nixon that Gurfein was “new, and, uh, he’s appreciative.” Ten minutes later, in a telephone conversation with Secretary of State William Rogers, Nixon said that Gurfein might be thinking of promotion, which would be up to the president.

Mitchell and Nixon could not have been more wrong about the corruptibility of Murray Gurfein. Times lawyers were concerned because he had been a military intelligence officer. But if that played any part in Gurfein’s attitude, it was to make him skeptical, demanding that the government’s lawyers point to something potentially dangerous in the Pentagon Papers. Government counsel at first would not cite dangerous passages. Their strategy was to seek an all-out victory, a judicial decision that publication of highly classified documents was impermissible without any particularized examination of their content. But Judge Gurfein kept asking for particulars. On that first day, Tuesday, he granted a temporary restraining order that stopped publication. On Friday the Post began publishing. The same day, Judge Gurfein held a day-long hearing on whether to follow his temporary restraint of the Times with a longer-lasting injunction. Bickel told the judge about the Washington Post story and said: “The Government’s position in this court, your Honor, was that grave danger to the national security would occur if another installment of a story that the Times had were published. Another installment of that story has been published. The Republic stands. And it stood the first three days.”

The next day, Saturday, Judge Gurfein rejected the government’s call for an injunction. His opinion included an eloquent passage that the authors use as an epigraph for this book:

A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.

The Times lost in the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which reversed Judge Gurfein. The Post won in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. On Friday morning, June 25, the Supreme Court granted review in both cases, setting argument for the next morning at 11. There was one crucial moment in the argument. Justice Potter Stewart asked Professor Bickel this question:

Let us assume that when the members of the court go back and open up this sealed record we find something there that absolutely convinces us that its disclosure would result in the sentencing to death of 100 young men whose only offense had been that they were 19 years old and had low draft numbers. What should we do?

Bickel said there should be a statute authorizing injunctions in specific terms; the absence of one had been a main theme of his argument. But Justice Stewart persisted. Suppose there was no relevant statute. “You would say the Constitution requires that it be published, and that these men die, is that it?” Bickel gave an answer that troubled some First Amendment purists but that may have won the case for the newspapers.

“No,” Bickel said, “I am afraid that my inclinations to humanity overcome the somewhat more abstract devotion to the First Amendment in a case of that sort….”

The Supreme Court decided the cases on June 30: just fifteen days after the litigation began in Judge Gurfein’s courtroom. It was not, as often assumed, a clear victory for the First Amendment. Justices Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas took a seemingly absolute view that the First Amendment bars injunctions against the press. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. said only proof that publication “must inevitably, directly and immediately” have disastrous consequences could justify even an interim restraining order. Justice Thurgood Marshall agreed with Bickel that there was no statute authorizing this kind of injunction and said it was up to Congress, not the courts, to decide whether there should be one. That was four votes for the newspapers. Justices Stewart and Byron White said they were convinced that some items in the Pentagon Papers raised the possibility of danger to the national security. But the First Amendment had been interpreted to disfavor prior restraints—injunctions—and there was no showing here, as Justice Stewart put it, of likely “direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our nation or its people.” Justice White added that a criminal prosecution would face a less demanding constitutional test—virtually inviting one, to the distress of the newspapers. The importance of the 6-to-3 vote for the newspapers, for all its diverse bases, is clear if one considers what a Supreme Court judgment enjoining further publication would have done to judicial and press attitudes in the following years.

Were there in fact any dangerous secrets in the Pentagon Papers? Erwin N. Griswold, who as solicitor general argued the case for the government in the Supreme Court, wrote later, “I have never seen any trace of a threat to the national security from the publication.” David Rudenstine concluded otherwise, somewhat ambiguously, in his scholarly 1996 book, The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers. He argued that though the papers’ history stopped on March 31, 1968, there were passages that could have done some injury to national security in 1971. Prados and Porter disagree. They say that Rudenstine analyzed only government claims and testimony, not the documents themselves. They publish for the first time, with only a few redactions, what was the ultimate government argument for secrecy: Griswold’s secret brief in the Supreme Court, listing eleven parts of the Pentagon Papers that he said “involve a serious risk of immediate and irreparable harm to the United States and its security.” (Griswold wrote the brief overnight, with little knowledge of the material.)

The first of those eleven items was the four whole volumes of the papers on attempted peace negotiations—volumes, Prados and Porter point out, that were not part of the leak and were never seen by the newspapers. Another of the eleven was an assertion that the papers included names of “CIA agents still active in Southeast Asia.” Prados and Porter note that almost all the names were of well-known officials such as Richard Helms, and others of men who were no longer with the CIA. They deal effectively with all the other supposed dangers in the Griswold list.

One episode during the Pentagon Papers litigation showed dramatically that skepticism is in order when officials claim that disclosure will bring disaster. During the argument before the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, a government lawyer pointed to a communications intercept from the Gulf of Tonkin incident as a secret The Washington Post might publish. That certainly had the aura of a genuine secret. When the judges left the bench to confer, the Post’s Pentagon reporter, George Wilson, who was there, pondered it. It seemed familiar. He looked at a congressional committee report that he had with him. There, in a published report, was the intercept. The Post’s lawyers sent the committee report in to the judges. The secret was exploded.

3.

Inside the Pentagon Papers tells a wonderful story, and it is a significant book today. For the effects that the Pentagon Papers controversy had on some institutions in our society seem to have worn off.

The press, for one, has retreated from the boldness it showed in 1971. The New York Times and The Washington Post have apologized for having failed adequately to examine the government’s claims in the run-up to the Iraq war. The press was slow to give serious coverage to the Bush administration’s assaults on civil liberty, such as the claim that the President can imprison American citizens indefinitely as alleged “enemy combatants” without trial or access to counsel. (Newspapers have more recently emerged from their torpor, for example in vigorously reporting the widespread torture of prisoners held by the US in Iraq, Guantánamo, and Afghanistan, and the Bush administration’s legal memoranda that opened the way to torture. Even there, though, some of the breakthrough reporting came from Seymour Hersh and Jane Mayer in The New Yorker.)

The crucial lesson of the Pentagon Papers and then Watergate was that presidents are not above the law. So we thought. But today government lawyers argue that the president is above the law—that he can order the torture of prisoners even though treaties and a federal law forbid it. John Yoo, a former Justice Department official who wrote some of the broad claims of presidential power in memoranda, told Jane Mayer recently that Congress does not have power to “tie the president’s hands in regard to torture as an interrogation technique.” The constitutional remedy for presidential abuse of his authority, he said, is impeachment. Yoo also told Ms. Mayer that the 2004 election was a “referendum” on the torture issue: the people had spoken, and the debate was over. And so, in the view of this prominent conservative legal thinker, a professor at the University of California law school in Berkeley, an election in which the torture issue was not discussed has legitimized President Bush’s right to order its use.

The notion that we have a plebiscitary democracy in this country would have astonished James Madison and the other Framers of the Constitution, who thought they were establishing a federal republic of limited powers. So would the idea that the president can ignore laws passed by Congress. One of the fundamental constitutional checks against abuse of power, as the Framers saw it, was the separation of powers in three branches of the federal government: executive, legislative, judicial. If one overreached, they thought, another would curb its abuse.

Congress as an institution has hardly exercised its checking power since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. It gave President Bush greatly expanded investigative and prosecutorial authority in the Patriot Act. It has only intermittently challenged the unprecedented secrecy he has imposed on government activity.

That leaves the third branch, the courts. In the context of the “war on terrorism,” would they decide a case like the Pentagon Papers the same way today? No one can be sure. But lately there have been signs that judges are unwilling to be cowed by the claims, made since September 11, of unreviewable presidential power. The Supreme Court ruled last year that citizens held without trial as “enemy combatants” must have an opportunity to answer official suspicions, and held that prisoners at Guantánamo Bay may file petitions in federal courts for release on habeas corpus.

The Supreme Court made its decision on citizens held without trial in the case of Yaser Esam Hamdi. Rather than tell him its reasons for holding him and letting him answer, the government sent Hamdi back to his home in Saudi Arabia. Then, the other day, a federal district judge in South Carolina ordered the release of the other American held as an “enemy combatant,” Jose Padilla. The judge—Henry F. Floyd, nominated by President Bush in 2003—said: “The court finds that the president has no power, neither express nor implied, neither constitutional nor statutory, to hold petitioner as an enemy combatant.” To allow that, Judge Floyd said,

would not only offend the rule of law and violate this country’s tradition, but it would also be a betrayal of this nation’s commitment to the separation of powers that safeguards our democratic values and individual liberties.

It was only a trial judge speaking, and officials immediately said they would appeal. His decision affected one American citizen while mistreatment of prisoners overseas during interrogation, as FBI reports among other things have shown, remains inadequately investigated, much less forbidden. But that a trial judge reached those conclusions, and had the courage to express them, meant something. Perhaps, in the courts, the spirit of the Pentagon Papers lives.

—March 10, 2005

This Issue

April 7, 2005