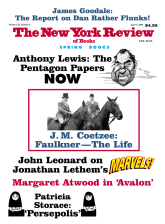

1.

“Now I realise for the first time,” wrote William Faulkner to a woman friend, looking back from the vantage point of his mid-fifties, “what an amazing gift I had: uneducated in every formal sense, without even very literate, let alone literary, companions, yet to have made the things I made. I don’t know where it came from. I don’t know why God or gods or whoever it was, selected me to be the vessel.”

The disbelief Faulkner lays claim to is a little disingenuous. For the kind of writer he wanted to be, he had all the education, even all the book-learning, he needed. As for company, he stood to gain more from garrulous oldsters with gnarled hands and long memories than from effete littérateurs. Nevertheless, a measure of astonishment is in order. Who would have guessed that a boy of no great intellectual distinction from small-town Mississippi would become not only a famous writer, celebrated at home and abroad, but the kind of writer he in fact became: the most radical innovator in the annals of American fiction, a writer to whom the avant-garde of Europe and Latin America would go to school?

Of formal education Faulkner certainly had a minimum. He dropped out of high school in his junior year (his parents seem not to have made a fuss), and though he briefly attended the University of Mississippi, that was only by grace of a dispensation for returned servicemen (of Faulkner’s war service, more below). His college record was undistinguished: a semester of English (grade: D), two semesters of French and Spanish. For this explorer of the mind of the post-bellum South, no courses in history; for the novelist who would weave Bergsonian time into the syntax of memory, no studies in philosophy or psychology.

What the rather dreamy Billy Faulkner gave himself in place of schooling was a narrow but intense reading of fin-de-siècle English poetry, notably Swinburne and Housman, and of three novelists who had given birth to fictional worlds lively and coherent enough to supplant the real one: Balzac, Dickens, and Conrad. Add to this a familiarity with the cadences of the Old Testament, Shakespeare, and Moby-Dick, and, a few years later, a quick study of what his older contemporaries T.S. Eliot and James Joyce were up to, and he was ready armed. As for materials, what he heard around him in Oxford, Mississippi, turned out to be more than enough: the epic, told and retold endlessly, of the South, a story of cruelty and injustice and hope and disappointment and victimization and resistance.

Billy Faulkner had barely quit school when the First World War broke out. Captivated by the idea of becoming a pilot and flying sorties against the Hun, he applied in 1918 to be taken into the Royal Air Force. Desperate for fresh manpower, the RAF sent him to Canada on a training course. Before he could make his first solo flight, however, the war ended.

He returned to Oxford wearing an RAF officer’s uniform and affecting a British accent and a limp, the consequence, he said, of a flying accident. To friends he also confided that he had a steel plate in his skull.

He sustained the aviator legend for years; he began to play it down only when he became a national figure and the risk of exposure loomed too large. His dreams of flying were not abandoned, however. As soon as he had the money to spare, in 1933, he took flying lessons, bought his own plane, and briefly operated a flying circus: “WILLIAM FAULKNER’S (Famous Author) AIR CIRCUS,” ran the advertisement.

Faulkner’s biographers have made much of his war stories, treating them as more than just the concoctions of a puny and unprepossessing youth desperate to be admired. Frederick R. Karl believes that “the war turned [Faulkner] into a storyteller, a fictionist, which may have been the decisive turnabout of his life.” The ease with which he duped the good people of Oxford, Karl says, proved to Faulkner that, artfully contrived and convincingly expounded, a lie can beat the truth, and thus that one can make a living out of fantasy.

Back home Faulkner led a drifting life. He wrote poems about “epicene” (by which he seems to have meant narrow-hipped) women and his unrequited longings for them, poems that even with the best will in the world one cannot call promising; he began to sign his name not “Falkner,” as he was born, but “Faulkner”; and, following the pattern of the male Falkners, he drank heavily. For some years, until he was dismissed for poor performance, he held a sinecure as postmaster of a small post office, where he occupied office hours reading and writing.

For someone so determined to follow his own inclinations, it is odd that, rather than packing his bags and heading for the bright lights of the metropolis, he chose to remain in the town of his birth, where his pretensions were regarded with sardonic amusement. Jay Parini, his latest biographer, suggests that he found it hard to be out of reach of his mother, a woman of some sensibility who seems to have had a deeper relation with her eldest son than with a dull and spineless husband.

Advertisement

On forays to New Orleans Faulkner developed a circle of bohemian friends and met Sherwood Anderson, annalist of Winesburg, Ohio, whose influence on him he was later at pains to minimize. He began to publish short pieces in the New Orleans press; he even dipped into literary theory. Willard Huntington Wright, a disciple of Walter Pater, made a particular impression on him. In Wright’s The Creative Will (1916) he read that the true artist is solitary by nature, “an omnipotent god who moulds and fashions the destiny of a new world, and leads it to an inevitable completion where it can stand alone, self-moving, independent,” leaving its creator exalted of spirit. The type of the artist-demiurge, suggests Wright, is Honoré de Balzac, much to be preferred to Émile Zola, a mere copyist of a preexisting reality.

In 1925 Faulkner made his first trip abroad. He spent two months in Paris and liked it: he bought a beret, grew a beard, began work on a novel—soon to be abandoned—about a painter with a war wound who goes to Paris to further his art. He hung out at James Joyce’s favorite café, where he caught a glimpse of the great man but did not approach him.

All in all, nothing in the record suggests more than a would-be writer of unusual doggedness but no great gifts. Yet soon after his return to the United States he would sit down and write a 14,000-word sketch bursting with ideas and characters, the groundwork for his great novels of the years between 1929 and 1942. The manuscript contained, in embryo, Yoknapatawpha County.

As a child Faulkner had been inseparable from a slightly older friend named Estelle Oldham. The two were in some sense betrothed. When the time came, however, the Oldham parents, disapproving of the shiftless youth, married Estelle off to a lawyer with better prospects. When Estelle returned to the parental home it was as a divorced woman of thirty-two with two small children.

Faulkner seems to have had doubts about the wisdom of pursuing the relationship. “It’s a situation which I engendered and permitted to ripen which has become unbearable,” he confided in a letter. But honor forbade him to withdraw. He and Estelle were accordingly married.

Estelle must have had her doubts too. During the honeymoon she may or may not have tried to drown herself. The marriage itself turned out to be unhappy, worse than unhappy. “They were just terribly unsuited for each other,” their daughter, Jill, told Parini. “Nothing about the marriage was right.” Estelle was an intelligent woman, but she was used to spending money freely and to having servants carry out her every wish. Life in a dilapidated old house with a husband who spent his mornings scribbling and his afternoons replacing rotten timbers and putting in plumbing must have come as a shock to her. A child was born but died at two weeks. Jill was born in 1933. Thereafter sexual relations between the Faulkners seem to have ceased.

Together and separately, William and Estelle drank to excess. In late middle age Estelle pulled herself together and went on the wagon; William never did. He had affairs with younger women that he was not competent or careful enough to conceal; from scenes of raging jealousy the marriage by degrees dwindled into, in the words of Faulkner’s first biographer, Joseph Blotner, “desultory domestic guerrilla warfare.”

Nevertheless, for thirty-three years, until Faulkner’s death in 1962, the marriage endured. Why? The most mundane explanation is that until well into the 1950s, Faulkner could not afford a divorce—that is to say, he could not, in addition to the troops of Faulkners or Falkners, to say nothing of Oldhams, who were dependent on his earnings, afford to support Estelle and three children in the style she would have demanded, and at the same time relaunch himself decently in society. Less easily demonstrable is Karl’s claim that at some deep level Faulkner needed Estelle. “Estelle could never be disentangled from the deepest reaches of [Faulkner’s] imagination,” Karl writes. “Without Estelle…he could not have continued [to write].” She was his “belle dame sans merci”—“that ideal object man worships from a distance who is also…destructive.”

By choosing to marry Estelle, by choosing to make his home in Oxford amid the Falkner clan, Faulkner took on a formidable challenge: how to be patron and breadwinner and paterfamilias to what he privately called “[a] whole tribe…hanging like so many buzzards over every penny [I] earn,” while at the same time serving his inner daimon. Despite an Apollonian ability to immerse himself in his work—“a monster of efficiency,” Parini calls him—the project wore him down. To feed the buzzards, the one blazing genius of American literature of the 1930s had to put aside his novel-writing, which was all that really mattered to him, first to churn out stories for popular magazines, later to write screenplays for Hollywood.

Advertisement

The trouble was not so much that Faulkner was unappreciated in the community of letters as that there was no room in the economy of the 1930s for the profession of avant-garde novelist (today Faulkner would be a natural for a major fellowship). Faulkner’s publishers, editors, and agents—with one miserable exception—had his interests at heart and did their best on his behalf, but it was not enough. Only after the appearance of The Portable Faulkner, a selection skillfully put together by Malcolm Cowley in 1945, did American readers wake up to what they had in their midst.

The time spent writing stories was not all wasted. Faulkner was an extraordinarily tenacious reviser of his own work (in Hollywood he impressed by his ability to fix up dud scripts by other writers). Revisited and reconceived and reworked, material that made its first appearance in The Saturday Evening Post or The Woman’s Home Companion resurfaced transmogrified in The Unvanquished (1938), The Hamlet (1940), and Go Down, Moses (1942), books that straddle the line between story collection and novel proper.

The same buried potential cannot be claimed of his screenplays. When Faulkner arrived in Hollywood in 1932, riding on passing notoriety as the author of Sanctuary (1931), he knew nothing of the industry (in his private life he disdained movies as much as he disliked loud music). He had no gift for putting together snappy dialogue. Furthermore, he soon acquired a reputation as an undependable lush. From a high of $1,000 a week his salary had by 1942 dropped to $300. In the course of a thirteen-year career he worked with sympathetic directors like Howard Hawks, was friendly with celebrated actors like Clark Gable and Humphrey Bogart, acquired an attractive and attentive mistress; but nothing that he wrote for the movies proved worth rescuing.

Worse than that: his screenwriting had a bad effect on his prose. During the war years Faulkner worked on a succession of scripts of a hortatory, uplifting, patriotic nature. It would be a mistake to load all the blame for the overblown rhetoric that mars his late prose onto these projects, but he himself came to recognize the harm Hollywood had done him. “I have realized lately how much trash and junk writing for movies corrupted into my writing,” he admitted in 1947.

There is nothing exceptional in the story of Faulkner’s struggles to make accounts balance. From the beginning he thought of himself as a poète maudit, and it is the lot of the poète maudit to be disregarded and underpaid. All that is surprising is that the burdens he took on—the high-spending wife, the impecunious relatives, the disadvantageous studio contracts—should have been borne so tenaciously (though with much griping on the side), even at the cost of his art. Loyalty is as strong a theme in Faulkner’s life as in his writing, but there is such a thing as mad loyalty, mad fidelity (the Confederate South was full of it).

In effect, Faulkner spent his middle years as a migrant worker sending his pay packet home to Mississippi; the biographical record is largely a record of dollars and cents. In Faulkner’s worryings over money Parini rightly discerns something crazy. “Money is rarely just money,” Parini writes. “The obsession with money that seems to dog Faulkner throughout his life must, I think, be regarded as a measure of his waxing and waning feelings of stability, value, purchase on the world,…a means of calculating his reputation, his power, his reality.”

A position as writer in residence on some quiet Southern college campus might have been the salvation of William Faulkner, giving him a steady income and demanding not much in return, allowing him time for his own work. A canny Robert Frost had since 1917 been showing that one could use the bardic aura to secure oneself academic sinecures. But lacking a high school diploma, mistrustful of talk that sounded too “literary” or “intellectual,” Faulkner made no return to academe until 1946, when he was persuaded to speak to students at the University of Mississippi. The experience was not as bad as he had feared; at the age of sixty, at a more or less nominal salary, he joined the University of Virginia as writer in residence, a position he retained until his death.

One of the ironies of the life of this academic laggard is that he had probably read more widely, if less systematically, than most college professors. In Hollywood, said the actor Anthony Quinn, even though he wasn’t much of a screenwriter he had “a tremendous reputation as an intellectual.” Another irony is that Faulkner was adopted by the New Critics as an author whose prose could rewardingly be assigned to college students to dissect. Cleanth Brooks, doyen of the New Criticism, records that Faulkner was “perfect for the classroom…. There was…so much to unfold that had been carefully and ingeniously folded by the author.” Thus Faulkner became the darling of the New Haven formalists as he was already the darling of the French existentialists, without being quite sure what either formalism or existentialism was.

2.

The Nobel Prize for literature, awarded for 1949, presented in 1950, made Faulkner famous, even in America. Tourists came from far and wide to gawk at his house in Oxford, to his vast irritation. Reluctantly he emerged from the shadows and began to behave like a public figure. From the State Department came invitations to go abroad as a cultural ambassador, which he dubiously accepted. Nervous before the microphone, even more nervous fielding “literary” questions, he prepared for sessions by drinking heavily. But once he had developed a patter to cope with journalists, he grew more comfortable with the role. He was ill-informed about foreign affairs—he did not read newspapers—but that suited the State Department well enough. His visit to Japan was a striking public relations success; in France and Italy he received huge attention from the press. As he remarked sardonically, “If they believed in my world in America the way they do abroad, I could probably run one of my characters for President…maybe Flem Snopes.”

Less impressive were Faulkner’s interventions back home. Pressure was building on the South and its segregated institutions. In letters to editors of newspapers, he began to speak out against abuses and to urge fellow white Southerners to accept the Negro as a social equal.

There was a backlash. “Weeping Willie Faulkner” was denounced as a pawn of Northern liberals, as a Communist sympathizer. Even though he was never in physical danger, he foresaw, as he confided to a Swedish friend, that he might have to flee the country “something as the Jew had to flee from Germany during Hitler.”

He was of course overdramatizing. His views on race were never radical and, as the political atmosphere grew more charged and took on states’ rights overtones, descended into confusion. Segregation was an evil, he said; nevertheless, if integration were forced upon the South he would resist (in a rash moment he even said he would take up arms). By the late 1950s his position had become so out of date as to be positively quaint. The civil rights campaign should adopt as its watchwords, he said, decency, quietness, courtesy, and dignity; the Negro should learn to deserve equality.

It is easy enough to disparage Faulkner’s forays into race relations. In his personal life his behavior toward African-Americans seems to have been generous, kindly, but, unavoidably, patronizing: he belonged, after all, to a patron class. In his political philosophy he was a Jeffersonian individualist; it was this, rather than any residue of racism, that made him suspicious of black mass movements. If his scruples and equivocations soon rendered him irrelevant to the civil rights struggle, his courage in taking any stand at all, at the time when he did, should not be forgotten. His public statements made him somewhat of a pariah in his home town, and had more than a little to do with his decision, after his mother’s death in 1960, to quit Mississippi and move to Virginia. (At the same time, it must be said, the prospect of riding to the hounds with the Albermarle County Hunt was a powerful drawing card: Faulkner in his last years regarded himself as pretty much written out, and foxhunting became the new passion of his life.)

Faulkner’s interventions were ineffectual not because he was stupid about politics but because the appropriate vehicle for his political insights was not the essay, much less the letter to the editor, but the novel, and in specific the kind of novel he invented, with its unequaled rhetorical resources for interweaving past and present, memory and desire.

The territory on which Faulkner the novelist deployed his best resources was a South that bears a strong resemblance to the real South of his day—or at least the South of his youth—but is not all of the South. Faulkner’s South is a white South haunted by black presences. Even Light in August, which is more clearly about race and racism than his other books, has at its center not a black man but a man whose fate it is to confront or be confronted with blackness as an interpellation, an accusation from outside himself.

As historian of the modern South, Faulkner’s abiding achievement is the Snopes trilogy (The Hamlet, 1940; The Town, 1957; The Mansion, 1959), in which he tracks the takeover of political power by an ascendant poor white class in a revolution as quiet, implacable, and amoral as a termite invasion. His chronicle of the rise of the redneck entrepreneur is at the same time mordant and elegiac and despairing: mordant because he detests what he sees as much as he is fascinated by it; elegiac because he loves the old world that is being eaten up before his eyes; and despairing for many reasons, not least of which are, first, that the South he loves was built, as he knows better than anyone, on twin crimes of dispossession and slavery; second, that the Snopeses are just another avatar of the Falkners, thieves and rapists of the land in their day; and therefore, third, that as critic and judge he, William “Faulkner,” has no ground to stand on.

No ground unless he falls back on the eternal verities. “Courage and honor and pride, and pity and love of justice and of liberty” is the litany of virtues recited in Go Down, Moses by Ike McCaslin, who is pretty much spokesman for Faulkner’s wished-for, ideal self, a man who, having taken stock of his history and of the diminished and fast-diminishing world around him, renounces his patrimony, abjures fatherhood (thus putting an end to the procession of the generations), and becomes a simple carpenter.

Courage and honor and pride: to his litany Ike might have added endurance, as he does elsewhere in the same story: “Endurance…and pity and tolerance and forbearance and fidelity and love of children….” There is a strongly moralistic strain in Faulkner’s later work, a stripped-down Christian humanism stubbornly held to in a world from which God has retired. When this moralism proves unconvincing, as it often is, that is usually because Faulkner has failed to find an adequate fictional vehicle for it. The frustrations he experienced in putting together A Fable (written 1944–1953, published 1954), which he intended to be his magnum opus, were precisely in finding a way to embody his antiwar theme. The exemplary figure in A Fable is Jesus reincarnated in and re-sacrificed as the unknown soldier; elsewhere in the late work he is the simple, suffering black man or, more often, black woman, who by enduring an unendurable present keeps alive the germ of a future.

3.

For a man who lived an uneventful and largely sedentary life, William Faulkner has evoked prodigious biographical energies. The first major biographical monument was erected in 1974 by Joseph Blotner, a younger colleague from the University of Virginia whom he clearly liked and trusted, and whose two-volume Faulkner: A Biography provides a full and fair treatment of Faulkner’s outward life. Even Blotner’s one-volume, 400,000-word condensation (1984) may, however, prove too rich in detail for most readers.

Frederick R. Karl’s huge tome William Faulkner: American Writer (1989) has as its aim “to understand and interpret [Faulkner’s] life psychologically, emotionally, and literarily.” There is much in Karl’s work that is admirable, including undaunted ventures into the maze of Faulkner’s compositional practices, which involved working on numbers of projects at the same time, shunting material from one to another.

As Karl justly observes, Faulkner is “the most historical of [America’s] important writers.” He treats Faulkner as an American responding creatively to the historical and social forces in which he is enmeshed. As literary biographer what he tries to comprehend is how a man so deeply suspicious of modernization and what it was doing to the South could in his novelistic practice have been the most radical modernist of his generation.

Karl’s Faulkner emerges as a figure of grandeur as well as pathos, a man who, perhaps in thrall to the Romantic image of the doomed artist, was prepared to sacrifice himself to the project of living through a destiny from which any rational person would have walked away. But Karl’s book is spoiled by continual reductive psychologizing. Thus, to give some slight examples, Faulkner’s neat handwriting—an editor’s dream—is taken as evidence of an anal personality, his silly lies about his time with the RAF as a sign of a schizoid personality, his attention to detail as proof of obsessiveness, his affair with a young woman as suggestive of incestuous desires for his own daughter.

“Often a lesser novel can provide more incisive biographical insights than a great one,” says Karl. If this is so—and not many contemporary biographers would disagree—then we confront a general problem about literary biography and the status of so-called biographical insights. May it not be that if the minor work seems to reveal more than the major work, what it reveals is worth knowing only in a minor way? Perhaps Faulkner—to whom the odes of John Keats were poetic touchstones—was indeed what he felt himself to be: a being of negative capability, one who disappeared into, lost himself in, his profoundest creations. “It is my ambition to be as a private individual, abolished and voided from history, leaving it markless,” he wrote to Cowley: “It is my aim…that the sum and history of my life…shall be…: He made the books and he died.”

Jay Parini is the author of biographies of John Steinbeck (1994) and Robert Frost (1999), and of two novels with a strong biographical content: The Last Station (1990), about the last days of Leo Tolstoy, and Benjamin’s Crossing (1997), about the last days of Walter Benjamin. Parini’s life of Steinbeck is solid but unremarkable. The Frost book is more self-reflective: biography, Parini muses, may be less like historiography than we like to think and more like novel-writing. Of the biographical novels, the one on Tolstoy is the more successful, perhaps because Parini has a multiplicity of accounts of life on Yasnaya Polyana to draw on. In the Benjamin book he spends too much time explaining who his self-absorbed hero is and why we should be interested in him.

Now, in One Matchless Time, Parini attempts what neither Blotner nor Karl offers: a critical biography, a reasonably full account of Faulkner’s life together with an assessment of his writings. There is a great deal to be said for what he has produced. Though he relies heavily on Blotner for the facts, he has gone further than Blotner in conducting interviews with the last generation of people to have known Faulkner personally, some of whom have interesting things to say. He has a fellow writer’s appreciation for Faulkner’s language, and expresses that appreciation vividly. Thus the prose of “The Bear” proceeds “with a kind of inexorable ferocity, as though Faulkner composed in excited reverie.” Though by no means hagiography, his book pays eloquent tribute to its subject: “What most impresses about Faulkner as writer is the sheer persistence, the will-to-power that brought him back to the desk each day, year after year…. [His] grit was…as much physical as mental; [he] pushed ahead like an ox through mud, dragging a whole world behind him.”

For a nonspecialist book like this, one of the first decisions to be made has to be whether it should reflect the critical consensus or take a strong individual line. By and large, Parini goes for a version of the consensus option. His scheme is to follow Faulkner’s life chronologically, interrupting the narrative with short critical essays of an introductory nature on individual works. In the right hands such a scheme could result in exemplary specimens of the critic’s art. But Parini’s essays are not up to exemplary standard. Those on the best-known books tend to be his best; of the rest, too many consist of not particularly deft synopsis plus summary of the critical debate, where what counts as debate tends to be rather humdrum academic inquiry.

As in Karl’s book, there is also a degree of questionable psychologism. Thus Parini offers a rather wild reading of As I Lay Dying—a short novel built around the grotesque journey on which the Bundren children take their mother’s corpse on the way to the grave—as a symbolic act of aggression by Faulkner against his own mother as well as a “perverse” wedding present to his wife. “Does Estelle supplant Miss Maud [his mother] in Faulkner’s mind?” asks Parini. “Such questions are beyond answers, but it’s the province of biography to ask them, to allow them to play over the text and trouble it.” Perhaps it is indeed the province of the biographer to trouble the text with fancies plucked out of the air; perhaps not. More to the point is whether either Faulkner’s mother or his wife interpreted the novel as a personal attack. There is no record that either did.

Parini’s explorations of Faulkner’s mind entail much talk of parts of the self, or selves within the self. Does Faulkner disapprove of the adulterous lovers in The Wild Palms? Answer: while “a part of his novelistic mind” condemns them, another part does not. Why does Faulkner in the late 1930s choose to focus on Flem Snopes, the beady-eyed, coldhearted social climber of the trilogy? “I suspect it has something to do with exploring his own aggressive self,” Parini writes. Having “succeeded beyond his own dreams,…[Faulkner] wanted to think on that success and to understand the impulses that might have led him to it.”

Was it really Faulkner’s “aggressive self” that produced the great novels of the 1930s, achievements at which Flem would have sneered, so little money did they make for their author? Does Flem’s crooked genius really resemble Faulkner’s baffled relationship with money, including his naiveté in signing a contract with Warner Brothers, the most stolidly unadventurous of the studios, that made him their slave for seven years?

All in all, Parini’s book is a puzzling mixture: on the one hand, a real feel for Faulkner as a writer; on the other, a readiness to vulgarize him. The worst example comes in remarks on Rowan Oak, the four-acre property that Faulkner bought in run-down state in 1929 and lived on until his death. Faulkner was prepared to spend money he didn’t have renovating Rowan Oak, Parini writes, because “he had a vision of antebellum luxury and superiority that he wanted, above all else, to re-create in his daily life…. The film Gone with the Wind…appeared [in 1939], taking the nation by storm. Faulkner didn’t need to see it. It was his life’s story.” Anyone who has read Blotner on daily life at Rowan Oak will know how far it was from the fantasy of Tara.

“A book is the writer’s secret life, the dark twin of a man: you can’t reconcile them,” says one of the characters in Mosquitoes (1927). Reconciling the writer with his books is a challenge that Blotner sensibly does not take on. Whether either Karl or Parini, in their different ways, brings together the man who signed his name “William Faulkner” with his dark twin is an open question.

The acid test is what Faulkner’s biographers have to say about his alcoholism. Here one should not pussyfoot about terminology. The notation on the file at the psychiatric hospital in Memphis to which Faulkner was regularly taken in a stupor was: “An acute and chronic alcoholic.” Though Faulkner in his fifties looked handsome and spry, that was only a shell. A lifetime’s drinking had begun to impair his mental functioning. “This is more than a case of acute alcoholism,” wrote his editor, Saxe Commins, in 1952. “The disintegration of a man is tragic to witness.” Parini adds the chilling testimony of Faulkner’s daughter: when drunk, her father could be so violent that “a couple of men” had to stand by to protect her and her mother.

Blotner does not try to understand Faulkner’s addiction, merely chronicles its ravages, describes its patterns, and quotes the hospital records. In Karl’s reading, drinking was the form that rebellion took in Faulkner, the way in which he defended his art against the pressures of family and tradition. “Take away the alcohol and, very probably, there would be no writer; and perhaps no defined person.” Parini does not demur, but sees a therapeutic purpose to Faulkner’s drinking as well. His binges were “downtime for the creative mind.” They were “useful in some peculiar way. They cleared away cobwebs, reset the inner clock, allowed the unconscious, like a well, to slow fill [sic].” Emerging from a binge was “as if he’d had a long and pleasant sleep.”

It is in the nature of addictions to be incomprehensible to those who stand outside them. Faulkner himself is of no help: he does not write about his addiction, does not, as far as we know, write from inside it (he was mostly sober when he sat down at his desk). No biographer has yet made sense of it; but perhaps making sense of an addiction, finding the words to account for it, giving it a place in the economy of the self, will always be a misconceived enterprise.

This Issue

April 7, 2005