1.

Zainab, a twenty-six-year-old woman, was watering the cattle at the well when the helicopters came to her village in South Darfur. Her eight-year-old son, Aziz, was helping her, and she had left four-year-old Abdulla with her husband in their thatched mud-and-brick house. She had never seen a helicopter before and for a while she wondered what it was. Then she saw the first bombs drop and listened to the cries of the villagers and the shouts of the men on camels as they began shooting people with their Kalashnikovs. As she ran toward the nearby trees, pulling Aziz behind her, she saw flames rising from the burning houses.

Later, when everything was quiet, Zainab and Aziz crept back. The village was absolutely quiet. No house was left standing. There were a few carcasses of cows and sheep, but the herds had vanished, taken by the men, and with them had gone Zainab’s own animals, her fifteen cows, thirty-five horses, and two camels, as well as all the sheep, chickens, and guinea fowl.

It was then that she saw the bodies, though it took her a few minutes to recognize them: the Janjaweed militias, who serve as the Sudanese army’s irregular forces, had hacked the heads off the men with machetes and taken them away, leaving their bodies behind. Her husband’s body was there, and those of her two brothers, her five brothers-in-law, and her father; her six sisters were dead too. Most of the younger boys had not been decapitated but, for no reason that she could understand, her son Abdulla’s head had been hacked off, and his body thrown onto the smoldering remains of their house, where it now lay burning. That day, in December 2003, some 150 people, all related to Zainab, were killed. Only Aziz and herself were left.

For the next five days, Zainab and Aziz hid in the long grass behind the village. Then they set out to find help. They had no shoes. As they walked, heading toward the town of Nyala, forty kilometers to the north, they met survivors of other massacres. They passed other burned-down villages. When they reached Nyala, Zainab found work with a man selling coffee in the market. Six months later, in June 2004, she heard that a camp for people like herself and Aziz was being opened nearby by the Sudan authorities, and she decided that they would be better off with a shelter.

Up to this point, Zainab’s story, atrocious as it is, is much like that of many thousands of people in Darfur, driven from their homes in the past two years by the helicopter gunships of the Sudanese army and the mounted Janjaweed militias in the rocky and inaccessible terrain of Darfur.

What happened next makes her more unfortunate than most. The camp of al-Jir in which she settled soon grew to 30,000 people. The Sudanese authorities suspected that its random collection of shacks harbored rebel fighters. In December 2004, at three o’clock in the morning, police and security officers arrived at the camp, rounded up sleeping and terrified people, and loaded them onto trucks, beating those who were reluctant to go. Zainab managed to drag her son to the safety of a nearby mosque and there they stayed until the police attacked again, using tear gas and taking away twenty-six of the men. At dawn, bulldozers manned by the police arrived to flatten the shelters. Ten thousand of the camp’s inhabitants were forced to walk to a new site, al-Sereif, an orderly encampment of white tents pegged in straight lines on a treeless, barren stretch of desert, easy to supervise and patrol. The other 20,000 melted away into the sprawling town of Nyala, Zainab and Aziz among them.

Zainab and her son are just two of an estimated two and a half million people displaced by Darfur’s civil war. According to the combined figures of the World Health Organization and nongovernmental organizations in the field, 15,000 people are dying every month—five hundred a day—from a combination of injuries and the illnesses that come from malnutrition and poverty, bringing the total to an estimated 350,000 to 400,000 people. These numbers are rising as the attacks and raids continue, while the start of the rains brings with them malaria, particularly the cerebral form that kills quickly, and water-borne diseases like cholera and dysentery. The riverbeds have flooded, and many of the tracks along which the food convoys travel have become impassable. Swarms of locusts have already been sighted in all three of Darfur’s states. But it is not the weather that the humanitarian agencies fear: it is the very nature of Darfur’s civil war.

In March, the International Crisis Group produced a report concluding that two years after the start of the conflict, all aspects of the situation, from the delivery of food to the security of the people, had deteriorated dramatically. Since then, Kofi Annan has warned that there are large and growing shortfalls in food and shelter. Though US aid alone has already amounted to $675 million—the US is the main donor—though wells have been dug, countless tons of sorghum and wheat delivered, though medical centers have been opened and programs of vaccination completed, much of the assistance is reaching only those in the camps inside Darfur. In the rural areas, far from roads where aid can be delivered or where the fighting makes access impossible, people already drastically strained in good years are now very close to disaster. Money used to reach Darfur from remittances from abroad and from the trade in livestock (30,000 camels a year were exported to Libya alone) but no longer.

Advertisement

The ten-thousand-foot mountain range at the center of Darfur, Jebel Marra, lies behind the lines in territory held by the rebel groups that have been fighting the Sudanese forces in Darfur for two years. The lines of fighting shift from week to week, and even though some international organizations have negotiated with the rebels, no single aid group has yet been able to establish a lasting presence and no food supplies get through. Late in March, a medical mission to Jebel Marra found that not a single village, out of the forty in the area, had any form of medical assistance or any medicines. In four of the villages, there had been sixty-five maternal deaths from septicemia and hemorrhaging that would all have been preventable in normal times, when women could travel to a nearby town to deliver their babies. In the same month, 248 children under five died of measles; many others were suffering from acute diarrhea, respiratory diseases, and from thyroid deficiency, there being no access to salt containing iodine.

Without antibiotics, oral rehydration salts, and anti-malaria drugs, one of the doctors on the mission told me, every child under five in the area is vulnerable. He had brought back a bottle of the water the more fortunate villagers have access to: it was dark brown and full of dirt. As he sees it, these forty villages, with some 150,000 inhabitants, are just a fraction of the number of other remote and unreachable places, cut off by the war from their normal patterns of trading and herding, where many people may die in the months to come.

2.

The causes of Zainab’s destroyed life lie far back in Darfur’s history, in a mixture of neglect by the central government and scarce resources in one of the least-developed places on earth. But the immediate reasons for the extreme precariousness of life there today are almost entirely a matter of politics, international as well as national. The British conquered Dar Fur, the land of the Fur, in 1916, by defeating the army of the autonomous Sultan Ali Dinar, and incorporated it into Sudan. The British then allocated land to the most powerful chiefs, assuming that their territories were held neatly by ethnic groups, though there were in fact some ninety tribes and subclans occupying a vast country of desert and savannah the size of France. But there was nothing neat about Darfur’s mix of mainly farming Africans and mainly nomadic Arabs, beyond the fact that they were all Muslim, even if centuries of intermarriage have made the people look alike, with dark skins and African features. Still, there was little serious hostility between them, until the droughts of the late Nineties drove farmers to enclose their best grazing land with thorn fences to keep the nomads out, and the impoverished nomads, feeling their way of life threatened, began searching for land to farm.

The year before Sudan became independent, in 1956, non-Muslims in the south began a revolt against the north which lasted until 1972. In June 1989, when the current president, Omar al-Bashir, took power in a military coup against the elected government of Sadiq al-Mahdi, he resumed the war in the south. In December 1999 he dissolved the parliament, banned opposition parties, and declared a state of emergency, which was marked by severe human rights abuses. In the next few years, while al-Bashir consolidated his power, his government ignored Darfur, engaged as it was in its long conflict with the rebel forces in the south.

There was at the time no shortage of weapons left over from the Eighties, from the days of Colonel Gaddafi’s dreams of an Arab belt stretching across the Sahel desert. The notion of Arab supremacy lived on among the nomads of the Sahel. In Darfur the rebel group calling themselves the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) protested against Khartoum’s neglect of the region and called for a united, culturally homogeneous Sudan, shared equally by Arabs and Africans, Christians and Muslims, and for more investment and power-sharing for Darfur. When their calls went unheeded in Khartoum, they joined forces with a second, extremist Islamist rebel group, called the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). In April 2003 both groups sent 260 men to attack El Fasher airport in South Darfur, destroying six Sudanese military aircraft and kidnapping an air force general.

Advertisement

Until that moment, no one had taken seriously the SLA’s complaints about the deteriorating situation in Darfur. Attention was on the south, where more than twenty years of civil war had left two million people dead. Fearing a second major conflict, the government now responded. Unable to use their own soldiers, many of them Darfurians who would not fight against their own people, they turned to a strat- egy that had served them well in the south: they armed the mounted Arab tribal militias. And for more than two years, from the spring of 2003, these Janjaweed—the name taken from the Arabic for “evil” and “horseman”—

supported by military helicopters, have been carrying out a scorched-earth policy against the rebels, both the SLA and the JEM, burning, raping, looting, and destroying sources of water as they go. For their part, the rebels have also killed and pillaged, though they have not committed atrocities on the same scale.

Initially, from the first signs of violence to the spring of 2004, the international community did almost nothing. Darfur remained a sideshow. Amnesty International and Médecins sans Frontières both published reports on the attacks, but the Sudanese government refused to allow in foreign organizations or journalists, while the West preferred to concentrate on securing peace in the south. It was only in March 2004, when the tenth anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda created pressure on Western nations to condemn the slaughter taking place in Darfur, that newspaper reporters arrived along with international agencies that were calling for action. By then, some 100,000 people had died.

The response was weak. Deadlines for sanctions came and went, and successive peace agreements stalled and were ignored. The government, which, in response to six separate United Nations Security Council resolutions, said it would neutralize the militias, did nothing. At a mini-summit in Libya on October 17, 2004, five African states voiced strong support for Sudan’s handling of the crisis. Between March and November 2004, a further 70,000 people died.

In the autumn of 2004, Colin Powell used the word “genocide” in his testimony to the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, and Kofi Annan asked Antonio Cassese, the Italian judge who had presided over the first hearings of the War Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, to carry out a mission to Darfur. Cassese, with a large team of experts, began work at the end of October. He started from two irrefutable facts: that over a million and a half people had by then been displaced and 200,000 turned into refugees, and that many villages in all three of Darfur’s states had been destroyed. In January, Cassese delivered his report. Many had hoped that he would declare the emergency a genocide, thus forcing immediate international action under the Genocide Convention, but Cassese concurred with the view of other human rights organizations that there had been no actual policy of genocide, even if some government officials and others involved had acted with genocidal intent. Rather, he concluded that the Janjaweed and the government of Sudan between them were guilty of “serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law” that might indeed amount to crimes against humanity and to war crimes, “no less serious and heinous than genocide.”

The report’s denial of northern genocide was a disappointment to many human rights groups. But Cassese also handed Kofi Annan a sealed list of fifty-one people who were to be investigated and tried at the International Criminal Court. Though secret, the names are widely assumed to include those of high-ranking government officials and members of the security cabal that has been powerful in Sudan since 1983, as well as President Omar al-Bashir himself. In early April, the Security Council, after much debate and many hesitations on the part of the US, which has opposed the idea of the International Criminal Court from the start, agreed to hand the names over to the chief ICC prosecutor at The Hague. But it was not until the end of June that the government of Sudan agreed to allow the prosecutor and his team into the country. Even then, Khartoum has so far rejected all suggestions of extraditing those charged, claiming that it will deal with the matter domestically in a new, special Sudanese court.

Since then intense concern about Darfur has died down. For 141 days, according to Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times, between January 10 and the end of May, President Bush did not once mention the word “Darfur.” With the recent peace agreement between north and south, US companies have become eager to share in Sudan’s developing oil wealth (and have begun to speculate that there may also be oil in Darfur), while the partnership between Washington and Khartoum over intelligence in the war on terrorism has been growing closer.

3.

Internally displaced people (IDPs) are the poor relations of the refugee world. When the UN Refugee Convention was drafted in 1951, it had in mind people fleeing communism and crossing borders into the West, and not those persecuted by their governments but unable, because of poverty and lack of mobility, to reach a neighboring state. But the anarchical nature of modern conflict, fought for the most part by internal forces rather than foreign ones, has meant that there are as many internally displaced people as there are refugees from other countries, if not more. Though the long years of Sudan’s civil wars have indeed driven people across the borders into Egypt, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda, Kenya, and the Central African Republic, only just over 200,000 have managed to leave Darfur in the last two years, and these are almost all in eleven camps in a remote corner of eastern Chad, where they are looked after by the UN High Commission for Refugees.

By contrast, most of the over two and a half million displaced people within Darfur, a third of the population, are in camps officially run by the Sudanese government, but staffed by international agencies. One fifth are children under five. Because of the war, there was very little planting last year. Combined with the drought, this resulted in a 90 percent drop in the harvest in areas that were once self- sustaining. Furthermore, with the continuing violence, few people are prepared to return to their lands to plant next year’s crop. The aid agencies, at the end of June, were feeding 1.8 million—out of a possible total of 3.5 million who may need food in the weeks to come. People recently arriving in the camps show signs of far more advanced malnutrition than before. As new arrivals, they can find no building materials for shelters. “Without an exit strategy,” said one agency worker, “we will still be here in twenty years’ time.” Care for the IDPs is farmed out across the UN agencies and to the ever-growing body of nongovernmental organizations.

There are seldom days when, somewhere across Darfur’s three states, there is not an attack on a foreign organization, whether by roaming bandits and looters who have multiplied during the months of fighting, or by the Janjaweed or the SLA and JEM. In December, two people working for Save the Children Fund were killed, and a few days later a member of Médecins sans Frontières was also killed; in March, a young woman working for USAID, leaving Nyala on her first mission, was shot in the head and blinded in one eye. Every few days, World Food Programme trucks are ambushed and looted by the Janjaweed, who take their drivers hostage or beat them up.

Moreover, most aid workers think that the Janjaweed, said to number anywhere between 5,000 and 20,000 tribesmen—accurate figures for these raiders are hard to come by, as are all such figures in Darfur—may no longer be controllable by the government. “With these militias, the government unleashed a monster,” a senior official in one of the UN agencies said to me. “It now has to be fed.”

In Darfur today, there is very little protection for anyone. And there is danger too for people in the towns who show sympathy for the rebels: the Sudan Organization Against Torture, which has its headquarters in London, has documented in Darfur alone over eight hundred cases of torture by the Sudanese army and the Janjaweed—burnings, beatings, incarceration in holes in the ground—in less than nine months.

There is constant danger for those in the camps as well. At first, the men left the camps by day in search of firewood. But as the surrounding countryside was picked bare, they had to travel further and further, only to be attacked and killed by marauding tribesmen. Women who tried to forage on their own were attacked and raped. A recent report by Médecins sans Frontières Holland described the cases of five hundred women seen by their doctors after being raped, of whom 82 percent had been raped while searching for wood or water. Twenty-eight percent had been raped more than once. In a Muslim country where victims are punished for being raped, this estimate is, MSF says, low. The 2,700 monitors sent by the African Union, who occasionally accompany women at some of the camps when they search for wood, can do little to prevent the assaults. Though armed, they use their weapons mostly to protect themselves. As for humanitarian workers, they have neither the mandate nor the power to come between attackers and attacked.

After MSF Holland published its report on rape last March, its work was constantly held up or obstructed, and two of its field workers were briefly detained, accused of crimes against the state and spying. Their subsequent report reinforced the conclusion that humanitarian assistance can never be a substitute for effective political and military action. After the disaster in Rwanda, where 800,000 unprotected people died, and the failure in Afghanistan (which was meant to be a model for humanitarian programs, but was not), Darfur has inevitably come to be seen as a test case for the lessons that should have been learned.

Like Iran in the 1980s, when the government let it be known that any mention of human rights violations by the revolutionary regime would only make things worse for people on the ground, the Sudanese government has made it clear that foreigners bringing in aid would be tolerated only if they kept to the rules. The rules, though nebulous, include delivering only the aid government officials want delivered, to the places they control, and keeping quiet about any violations that are observed. The Security Council resolution and the threat of the ICC prosecutor’s arrival have increased the foreign groups’ fears, not only of physical attacks when they leave the towns, but of expulsion. “If several Westerners were killed now,” said one aid worker—who, like the others, did not want to be named—“and the agencies leave, then many more Darfurians will die.”

The peace agreement signed between Khartoum and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and the confirmation on July 9 of John Garang, the SPLM leader, as vice-president of a new national unity government apparently marks the end of Africa’s longest-running civil war. African Union–sponsored negotiations over Darfur have been announced for August 24 and the US envoy, Jan Pronk, has said that the objective, now, is to have peace in Darfur before the end of the year. On paper, these moves sound promising. But Pronk’s words and the declaration of principles upholding democracy agreed on by Darfur’s rebels and the government on July 5 in Abuja are yet to be translated into any kind of action on the ground.

The camp of Otash lies some ten kilometers outside Nyala. It is a grim, barren place, where 30,000 people from fifty-seven villages scattered around South Darfur have gathered in search of safety. The igloo-shaped structures, stretching away as far as the eye can see, are made up of twigs and sticks, bits of paper and sacking, cardboard boxes and plastic bags. The sandstorms and high winds that blow in the dry season bring with them the detritus and scraps of paper and plastic that litter the edges of African villages, to snag on the branches of spiny acacia that surround the site.

Since so many adults have died in the fighting, Otash is full of orphans, small children taken in by the sheiks of different clans. One of these sheiks, who has three wives and seventeen children of his own—two of his sons were killed in a Janjaweed attack—has adopted not only the seven children of a brother who was killed, but ten others. The youngest is eighteen months. This man, once the owner of a large and prosperous farm, with many crops and animals, now has nothing. “I have my skin,” he says, “but I have lost my shadow.”

Everyone in the camp is dirty, for there is little water and no soap and the clothes the children wear are ragged and torn. There is just enough food, delivered by the World Food Programme, but the children say that they are hungry. And there is nothing for anyone to do, except sit inside the stifling igloos, out of the rains that have turned the camp into a sea of mud. Whether what the Janjaweed and the Sudanese government between them have done amounts to genocide or merely to crimes against humanity is not on their minds. Surviving the next few months is what they think about.

—July 14, 2005

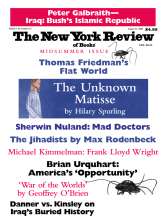

This Issue

August 11, 2005