1.

“There is no document of civilization,” Walter Benjamin maintained, in his most often-quoted line, “that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” He was writing—some sixty-five years ago—with particular reference to the spoils of victory carried in a triumphal procession: “They are called cultural treasures,” he said, but they had origins he could not “contemplate without horror.”

Benjamin’s provocation has now become a commonplace. These days, museum curators have grown uneasily self-conscious about the origins of such cultural treasures, especially those that are archaeological in nature or that come from the global south. A former curator of the Getty Museum is now on trial in Rome, charged with illegally removing objects from Italy, while Italian authorities are negotiating about the status of other objects from both the Getty and the Metropolitan Museum. Greece is formally suing the Getty for the recovery of four objects. The government of Peru has recently demanded that Yale University return five thousand artifacts that were taken from Machu Picchu in the early nineteen-hundreds—and all these developments are just from the past several months. The great international collectors and curators, once celebrated for their perceptiveness and perseverance, are now regularly deplored as traffickers in, or receivers of, stolen goods. Our great museums, once seen as redoubts of cultural appreciation, are now suspected strongrooms of plunder and pillage.

And the history of plunder—the barbarism beneath the civility—is often real enough, as I’m reminded whenever I visit my hometown in the Asante region of Ghana. In the nineteenth century, the kings of Asante—like kings everywhere—enhanced their glory by gathering objects from all around their kingdom and around the world. When the British general Sir Garnet Wolseley traveled to West Africa and destroyed the Asante capital, Kumasi, in a “punitive expedition” in 1874, he authorized the looting of the palace of King Kofi Karikari, which included an extraordinary treasury of art and artifacts. A couple of decades later, Major Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell (yes, the founder of the Boy Scouts) was dispatched once more to Kumasi, this time to demand that the new king, Prempeh, submit to British rule. Baden-Powell described this mission in his book, The Downfall of Prempeh: A Diary of Life with the Native Levy in Ashanti, 1895–96.

Once the King and his Queen Mother had made their submission, the British troops entered the palace, and, as Baden-Powell put it, “the work of collecting valuables and property was proceeded with.” He continued:

There could be no more interesting, no more tempting work than this. To poke about in a barbarian king’s palace, whose wealth has been reported very great, was enough to make it so. Perhaps one of the most striking features about it was that the work of collecting the treasures was entrusted to a company of British soldiers, and that it was done most honestly and well, without a single case of looting. Here was a man with an armful of gold-hilted swords, there one with a box full of gold trinkets and rings, another with a spirit-case full of bottles of brandy, yet in no instance was there any attempt at looting.

Baden-Powell clearly believed that the inventorying and removal of these treasures under the orders of a British officer was a legitimate transfer of property. It wasn’t looting; it was collecting.

The scandals in Africa did not cease with the end of European empires. Mali can pass a law against digging up and exporting the wonderful sculpture made in the old city of Djenne-jeno. But it can’t enforce the law. And it certainly can’t afford to fund thousands of archaeological digs. The result is that many fine Djenne-jeno terra cottas were dug up anyway in the 1980s, after the discoveries of the archaeologists Roderick and Susan McIntosh and their team were published. The terra cottas were sold to collectors in Europe and North America who rightly admired them. Because they were removed from archaeological sites illegally, much of what we would most like to know about this culture—much that we could have found out had the sites been preserved by careful archaeology—may now never be known.

Once the governments of the United States and Mali, guided by archaeologists, created laws specifically aimed at stopping the smuggling of stolen art, the open market for Djenne-jeno sculpture largely ceased. But people have estimated that in the meantime, perhaps a thousand pieces—some of them now valued at hundreds of thousands of dollars—left Mali illegally. In view of these enormously high prices, you can see why so many Malians were willing to help export their “national heritage.”

Modern thefts have not, of course, been limited to the pillaging of archaeological sites. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of art has been stolen from the museums of Nigeria alone, almost always with the complicity of insiders. And Ekpo Eyo, who once headed the National Museum of Nigeria, has rightly pointed out that dealers in New York and London have been less than eager to assist in their retrieval. Since many of these collections were well known to experts on Nigerian art, it shouldn’t have taken the dealers long to recognize what was going on.

Advertisement

In these circumstances—and with this history—it has been natural to protest against the pillaging of “cultural patrimony.”1 Through a number of declarations from UNESCO and other international bodies, a doctrine has evolved concerning the ownership of many forms of cultural property. In the simplest terms, it is that cultural property should be regarded as the property of its culture. If you belong to that culture, such work is, in the suggestive shorthand, your cultural patrimony. If not, not.

Part of what makes the grand phrase “cultural patrimony” so powerful, I suspect, is that it conflates, in confusing ways, the two primary uses of that confusing word “culture.” On the one hand, cultural patrimony refers to cultural artifacts: works of art, religious relics, manuscripts, crafts, musical instruments, and the like. Here “culture” is whatever people make and invest with significance through their creative work. Since significance is something produced through conventions, which are never individual and rarely universal, interpreting culture in this sense requires some knowledge of its social and historical context.

On the other hand, “cultural patrimony” refers to the products of a culture: the group from whose conventions the object derives its significance. Here the objects are understood to belong to a particular group, heirs to a transhistorical identity. The cultural patrimony of Nigeria, then, is not just Nigeria’s contribution to human culture—its contribution, as the French might say, to a civilization of the universal. Rather, it comprises all the artifacts produced by Nigerians, conceived of as a historically persisting people: and while the rest of us may admire Nigeria’s patrimony, it belongs, in the end, to them.

But what does it mean, exactly, for something to belong to a people? Most of Nigeria’s cultural patrimony was produced before the modern Nigerian state existed. We don’t know whether the terra-cotta Nok sculptures, made sometime between about 800 BC and 200 AD, were commissioned by kings or commoners; we don’t know whether the people who made them and the people who paid for them thought of them as belonging to the kingdom, to a man, to a lineage, or to the gods. One thing we know for sure, however, is they didn’t make them for Nigeria.

Indeed, a great deal of what people wish to protect as “cultural patrimony” was made before the modern system of nations came into being, by members of societies that no longer exist. People die when their bodies die. Cultures, by contrast, can die without physical extinction. So there’s no reason to think that the Nok have no descendants. But if Nok civilization came to an end and its people became something else, why should they have a special claim on those objects, buried in the forest and forgotten for so long? And even if they do have a special claim, what has that got to do with Nigeria, where, let us suppose, most of those descendants now live?

Perhaps the matter of biological descent is a distraction: proponents of the patrimony argument would surely be undeterred if it turned out that the Nok sculptures were made by eunuchs. They could reply that the Nok sculptures were found on the territory of Nigeria. And it is, indeed, a perfectly reasonable property rule that where something of value is dug up and nobody can establish an existing claim on it, the government gets to decide what to do with it. It’s an equally sensible idea that, when an object is of cultural value, the government has a special obligation to preserve it. The Nigerian government will therefore naturally try to preserve such objects for Nigerians. But if they are of cultural value—as the Nok sculptures undoubtedly are—it strikes me that it would be better for them to think of themselves as trustees for humanity. While the government of Nigeria reasonably exercises trusteeship, the Nok sculptures belong in the deepest sense to all of us. “Belong” here is a metaphor, of course: I just mean that the Nok sculptures are of potential value to all human beings.

2.

That idea is expressed in the preamble of the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of May 14, 1954, which was issued by a conference called by UNESCO:

Being convinced that damage to cultural property belonging to any people whatsoever means damage to the cultural heritage of all mankind, since each people makes its contribution to the culture of the world….

Framing the problem that way—as an issue for all mankind—should make it plain that it is the value of the cultural property to people and not to peoples that matters. It isn’t peoples who experience and value art; it’s men and women. Once you see that, then there’s no reason why a Spanish museum couldn’t or shouldn’t preserve a Norse goblet, legally acquired, let’s imagine, at a Dublin auction, after the salvage of a Viking shipwreck off Ireland. It’s a contribution to the cultural heritage of the world. But at any particular time it has to be in one place. Why shouldn’t Spaniards be able to experience Viking craftsmanship? After all, there is no lack of Viking objects in Norway. The logic of “cultural patrimony,” however, would call for the goblet to be shipped back to Norway (or, at any rate, to Scandinavia): that’s whose cultural patrimony it is.

Advertisement

And in various ways, we’ve inched closer to that position in the years since the Hague convention. The Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, adopted by the UNESCO General Conference in Paris in 1970, stipulated that “cultural property constitutes one of the basic elements of civilization and national culture, and that its true value can be appreciated only in relation to the fullest possible information regarding its origin, history and traditional setting”; and that “it is essential for every State to become increasingly alive to the moral obligations to respect its own cultural heritage.”

A state’s cultural heritage, it further decreed, included both work “created by the individual or collective genius of nationals of the State” and “cultural property found within the national territory.” The convention emphasized, accordingly, the importance of “prohibiting and preventing the illicit import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural property.” A number of countries now declare all antiquities that originate within their borders to be state property, which cannot be freely exported. In Italy, private citizens are free to own “cultural property,” but not to send it abroad.2

That notion of “origination” is interestingly elastic. Among the objects that the Italian government has persuaded the Getty to repatriate is a 2,300-year-old painted Greek vase and an Etruscan candelabrum. (There are at least forty more objects at that museum that the Italians are after.) In November, the Metropolitan Museum in New York seemed close to a deal with the Italians to return a two-and-a-half-millennium-old terra-cotta vase from Greece, known as the Euphronios krater. Rocco Buttiglione of the Italian Culture Ministry has declared that the ministry’s aim was “to give back to the Italian people what belongs to our culture, to our tradition and what stands within the rights of the Italian people.” I confess I hear the sound of Greeks and Etruscans turning over in their dusty graves: patrimony, here, equals imperialism plus time.

Plainly, special legal problems are posed by objects, like Nok art, where there is, as lawyers might say, no continuity of title. If we don’t know who last owned a thing, we need a rule about what should happen to it now. Where objects have this special status as a valuable “contribution to the culture of the world,” the rule should be one that protects that object and makes it available to people who will benefit from experiencing it. So the rule of “finders, keepers,” which may make sense for objects of less significance, will not do. Still, a sensible regime will reward those who find such objects, and give them an incentive to report not only what they have found but where and how they found it.

For an object from an archaeological site, after all, value comes often as much from knowing where it came out of the ground, what else was around it, how it lay in the earth. Since these articles seldom have current owners, someone needs to regulate the process of removing them from the ground and decide where they should go. It seems to me reasonable that the decision about those objects should be made by the government in whose soil they are found. But the right conclusion for them is not obviously that they should always stay in the country where they were buried. Many Egyptians—overwhelmingly Muslims who regard the religion of the Pharaohs as idolatrous—nevertheless insist that all the antiquities ever exported from Egypt’s borders are really theirs. You do not need to endorse Napoleon’s depredations in northern Africa to think that there is something to be said for allowing people in other countries the chance to see, close up, the arts of one of the world’s great civilizations. And it’s a painful irony that one reason we’ve lost information about cultural antiquities is the very regulation intended to preserve it. If, for example, I sell you a figure from Djenne-jeno with evidence that it came out of the ground in a certain place after the regulations came into force, then I am giving the authorities in the United States, who are committed to the restitution of objects taken illegally out of Mali, the very evidence they need.

Suppose that from the beginning, Mali had been encouraged and helped by UNESCO to exercise its trustee-ship of the Djenne-jeno terra cottas by licensing digs and educating people to recognize that objects removed carefully from the earth with accurate records of location are of greater value, even to collectors, than objects without this essential element of provenance. Suppose they had required that objects be recorded and registered before leaving, and stipulated that if the national museum wished to keep an object, it would have to pay a market price for it, the acquisition fund being supported by a tax on the price of the exported objects.

The digs encouraged by such a system would have been less well conducted and less informative than proper, professionally administered digs by accredited archaeologists. Some people would still have avoided the rules. But mightn’t all this have been better than what actually happened? Suppose, further, that the Malians had decided that in order to maintain and build their collections they should auction off some works they own. The partisans of cultural patrimony, instead of praising them for committing needed resources to protecting the national collection, would have excoriated them for betraying their heritage.

The problem for Mali is not that it doesn’t have enough Malian art. The problem is that it doesn’t have enough money. In the short run, allowing Mali to stop the export of much of the art in its territory has the positive effect of making sure that there is some world-class art in Mali for Malians to experience. But an experience limited to Malian art—or, anyway, art made on territory that’s now part of Mali—makes no more sense for a Malian than it does for anyone else. New technologies mean that Malians can now see, in however imperfectly reproduced a form, great art from around the planet; and such reproduction will likely improve. If UNESCO had spent as much effort to make it possible for great art to get into Mali as it has done to stop great art getting out, it would have been serving better the interests that Malians, like all people, have in a cosmopolitan aesthetic experience.

3.

How would the concept of cultural patrimony apply to cultural objects whose current owners acquired them legally in the normal way? You live in Ibadan, in the heart of Yorubaland in Nigeria. It’s the early Sixties. You buy a painted carving from a young man—an actor, painter, sculptor, all-around artist—who calls himself “Twin Seven Seven.” Your family thinks it’s a strange way to spend money. Time passes, and he comes to be seen as one of Nigeria’s most important modern artists. More cultural patrimony for Nigeria, right? And if it’s Nigeria’s, it’s not yours. So why can’t the Nigerian government just take it, as the natural trustees of the Nigerian people, whose property it is?

The Nigerian government would not in fact exercise its power in this way. (When antiquities are involved, though, a number of other states will do so.) It is also committed, after all, to the idea of private property. Of course, if you were interested in selling, it might provide the resources for a public museum to buy it from you (though the government of Nigeria probably thinks it has more pressing calls on its treasury). So far cultural property is just like any other property.

Suppose, though, the government didn’t want to pay. There’s something else it could do. If you sold your artwork, and the buyer, whatever his nationality, wanted to take the painting out of Nigeria, it could refuse permission to export it. The effect of the international regulations is to say that Nigerian cultural patrimony can be kept in Nigeria. An Italian law (passed, by the way, under Mussolini) permits its government to deny export to any artwork currently owned by an Italian, even if it’s a Jasper Johns painting of the American flag. But then most countries require export licenses for significant cultural property (generally excepting the work of living artists). So much for being the cultural patrimony of humankind.

Such cases are particularly troublesome, because Twin Seven Seven wouldn’t have been the creator that he was if he’d been unaware of and unaffected by the work of artists in other places. If the argument for cultural patrimony is that the art belongs to the culture that gives it its significance, most art doesn’t belong to a national culture at all. Much of the greatest art is flamboyantly international; much ignores nationality altogether. A great deal of early modern European art was court art or was church art. It was made not for nations or peoples but for princes or popes or ad majorem gloriam dei. And the artists who made it came from all over Europe. More importantly, in a line often ascribed to Picasso, good artists copy, great ones steal; and they steal from everywhere. Does Picasso himself—a Spaniard—get to be part of the cultural patrimony of the Republic of the Congo, home of the Vili people, one of whose carvings Matisse showed him at the Paris apartment of the American Gertrude Stein?

The problem was already there in the preamble to the 1954 Hague Convention that I quoted a little while back: “…each people makes its contribution to the culture of the world.” That sounds like whenever someone makes a contribution, his or her “people” makes a contribution, too. And there’s something odd, to my mind, about thinking of Hindu temple sculpture or Michelangelo’s and Raphael’s frescoes in the Vatican as the contribution of a people, rather than the contribution of the artists who made (and, if you like, the patrons who paid for) them. I’ve gazed in wonder at Michelangelo’s work in the Sistine Chapel and I will grant that Their Holinesses Popes Julius II, Leo X, Clement VIII, and Paul III, who paid him, made a contribution, too. But which people exactly made that contribution? The people of the Papal States? The people of Michelangelo’s native Caprese? The Italians?

This is clearly the wrong way to think about the matter. The right way is to take not a national but a trans-national perspective: to ask what system of international rules about objects of this sort will respect the many legitimate human interests at stake. The reason many sculptures and paintings were made and bought was that they should be looked at and lived with. Each of us has an interest in being able, should we choose, to live with art—an interest that is not limited to the art of our own “people.” And if an object acquires a wider significance, as part, say, of the oeuvre of a major artist, then other people will have a more substantial interest in being able to experience it. The object’s aesthetic value is not fully captured by its value as private property. So you might think there was a case for giving people an incentive to share it. In America such incentives abound. You can get a tax deduction by giving a painting to a museum. You get social prestige from lending your works of art to shows, where they can be labeled “from the collection of…” And, finally, you might earn a good sum by selling it at auction, while both allowing the curious a temporary look at it and providing for a new owner the pleasures you have already known. If it is good to share art in these ways with others, why should the sharing cease at national borders?

Here is a cautionary tale about the international system we have created. In the years following the establishment of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, curators at Afghan’s National Museum, in Kabul, grew increasingly worried about the security of the country’s non-Islamic antiquities. They had heard the mounting threats made by Islamic hard-liners who considered all figurative works to be blasphemous, and they confided their concerns to colleagues in other countries, begging them to take such artifacts out of Afghanistan for safekeeping. They knew about the destruction of an ancient Buddhist temple and its artworks by fundamentalist soldiers. They knew that centuries-old illuminated manuscripts kept in a library north of Kabul had been burned by Taliban zealots. They had heard the rumblings about a new wave of iconoclasm, and they took them seriously.

Finally, in 1999, Paul Bucherer, a Swiss scholar who was the director of the Fondation Bibliotheca Afghanica, negotiated an arrangement with more moderate Taliban officials, including the then Taliban minister for information and culture, along with President Rabbani of the Northern Alliance. The endangered artifacts would be shipped to a museum in Switzerland that had been set up specifically for the purpose of keeping these works out of harm’s way while the danger persisted. In the fall of 2000, Dr. Bucherer, with the help of Afghan museum officials, had crated up these endangered artifacts, ready to be shipped to Switzerland for temporary safekeeping. Switzerland, as a signatory of UNESCO treaties, simply required UNESCO approval to receive the shipment.

But while Paul Bucherer and his Afghan colleagues had managed to negotiate around the Taliban hard-liners, they hadn’t counted on the UNESCO hard-liners. And UNESCO refused to authorize the shipments. Various explanations were offered, but the objection came down to the 1970 UNESCO Agreement on the Illicit Traffic of Cultural Objects, and its strictures against involving moving objects from their country of origin. Indeed, at a UNESCO meeting that winter, experts in Central Asian antiquities actually denounced Dr. Bucherer for trying to destroy Afghan culture.3

People I know who have visited the National Museum in Kabul recount what the staff members there have told them. Museum workers were ordered to open drawers of antiquities by Taliban inspectors, in the wake of Mullah Omar’s February 2001 edict against pre-Islamic art. Here were drawers of extraordinary Bactrian artifacts and Ghandara heads and figurines. My friends recall the dead look in a curator’s eyes as he described how the Taliban inspectors responded to these extraordinary artifacts by taking out mallets and pulverizing them in front of him.

Would the ideologues of cultural nativism, those experts who insist that archaeological artifacts are meaningless outside their land of origin, find solace in the fact that these works were destroyed by Afghan hands, on Afghan soil?

Only in March 2001, after the notorious demolition of the Bamiyan Buddahs, did UNESCO officials relent. Fortunately, Afghan curators, with nobody to turn to, took it on themselves to hide some of the most valuable archaeological finds.4 These curators, including Omara Khan Massoudi, who is now director of the National Museum, did heroic work, and, today, UNESCO is helping with the restoration of damaged art. The problem in Afghanistan under the Taliban wasn’t so much the behavior of UNESCO bureaucrats as the conception of their task imposed upon them by the community of nations. The threat comes from the idea that even endangered art—endangered by a state whose government threatens it precisely because they don’t think it is a proper part of their own heritage—nevertheless properly belongs in the state whose cultural patrimony it is.

This is the ideology of the system to which the United States committed itself with the Senate’s ratification in 1972 of the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. (Characteristically, perhaps, it took another decade for this decision to turn into an actual act of Congress.) UNESCO, like all UN bodies, is the creature of the system of nations; while it speaks of World Heritage Sites, it is nevertheless bound to conceive them as ultimately at the disposal of nations. Because what it unites are nations, not human beings, it is impotent when what humanity needs is not what some state has decided to do. We will do well to recognize that iconoclasm is as much an expression of nationalism as idolatry: the human community needs to find ways to protect our common heritage from the iconoclasts, even when they are the masters of nations.

When we’re trying to interpret the concept of cultural property, we ignore at our peril what lawyers, at least, know: property is an institution, created largely by laws, which are best designed by thinking about how they can serve the human interests of those whose behavior they govern. If the laws are international laws, then they govern everyone. And the human interests in question are the interests of all of humankind. However self-serving it may seem, the British Museum’s claim to be a repository of the heritage not of Britain but of the world strikes me as exactly right. Part of the obligation, though, is to make those collections more widely available not just in London but elsewhere, through traveling collections, through publications, and through the World Wide Web.

It has been too easy to lose sight of the global constituency. The American legal scholar John Henry Merryman once offered some examples of how laws and treaties relating to cultural property have betrayed a properly cosmopolitan (he uses the word “internationalist”) perspective. “Though we readily deplore the theft of paintings from Italian churches,” he wrote, “if a painting is rotting in a church from lack of resources to care for it, and the priest sells it for money to repair the roof and in the hope that the purchaser will give the painting the care it needs, then the problem begins to look different.”5

So when I lament the modern thefts from Nigerian museums or Malian archaeological sites or the imperial ones from Asante, it’s because the property rights that were trampled upon in these cases flow from laws that I think are reasonable. I am not for sending every object “home.” Many of the Asante art objects now in Europe, America, and Japan were sold or given by people who had the right to dispose of them under the laws that then prevailed, laws that were perfectly reasonable. It may be a fine gesture to return things to the descendants of their makers—or to offer it to them for sale—but it certainly isn’t a duty. You might also show your respect for the culture it came from by holding on to it because you value it yourself. Furthermore, because cultural property has a value for all of us, we should make sure that those to whom it is returned are in a position to act as responsible trustees. Repatriation of some objects to poor countries with necessarily small museum budgets might just lead to their decay. Were I advising a poor community pressing for the return of many ritual objects, I might urge them to consider whether leaving some of them to be respectfully displayed in other countries might not be part of their contribution to cross-cultural understanding as well as a way to ensure their survival for later generations.

To be sure, there are various cases where repatriation makes sense. We won’t, however, need the concept of cultural patrimony to understand them. Consider, for example, objects whose meaning would be deeply enriched by being returned to the setting from which they were taken—site-specific art of one kind or another. Here there is an aesthetic argument for return. Or consider objects of contemporary ritual significance that were acquired legally from people around the world in the course of European colonial expansion. If an object is central to the cultural or religious life of a community, there is a human reason for it to find its place back with them.

But the clearest cases for repatriation are those where objects were stolen from people whose names we often know; people whose heirs, like the King of Asante, would like them back. As someone who grew up in Kumasi, I confess I was pleased when some of this stolen art was returned, thus enriching the new palace museum for locals and for tourists. Still, I don’t think we should demand everything back, even everything that was stolen; not least because we haven’t the remotest chance of getting it. Don’t waste your time insisting on getting what you can’t get. There must be an Akan proverb with that message.

There is, however, a more important reason: I actually want museums in Europe to be able to show the riches of the society they plundered in the years when my grandfather was a young man. And I’d rather that we negotiated not just the return of objects to the palace museum in Ghana, but a decent collection of art from around the world. Because perhaps the greatest of the many ironies of the sacking of Kumasi in 1874 is that it deprived my hometown of a collection that was, in fact, splendidly cosmopolitan. As Sir Garnet Wolseley prepared to loot and then blow up the Aban, the large stone building in the city’s center, European and American journalists were allowed to wander through it. The British Daily Telegraph described it as “the museum, for museum it should be called, where the art treasures of the monarchy were stored.” The London Times’s Winwood Reade wrote that each of its rooms “was a perfect Old Curiosity Shop.” “Books in many languages,” he continued, “Bohemian glass, clocks, silver plate, old furniture, Persian rugs, Kidderminster carpets, pictures and engravings, numberless chests and coffers…. With these were many specimens of Moorish and Ashantee handicraft.”

We shouldn’t become overly sentimental about these matters. Many of the treasures in the Aban were no doubt war booty as well. Still it will be a long time before Kumasi has a collection as rich both in our own material culture and in works from other places as the collections destroyed by Sir Garnet Wolseley and the founder of the Boy Scouts. The Aban had been completed in 1822. And how had the Asante king hit upon the project in the first place? Apparently, he had been deeply impressed by what he’d heard about the British Museum.6

We understand the urge to bring these objects “home.” A Norwegian thinks of the Norsemen as her ancestors. She wants not just to know what their swords look like but to stand close to an actual sword, wielded in actual battles, forged by a particular smith. Some of the heirs to the kingdom of Benin, the people of South West Nigeria, want the bronze their ancestors cast, shaped, handled, wondered at. They would like to wonder at—if we will not let them touch—that very thing. The connection people feel to cultural objects that are symbolically theirs, because they were produced from within a world of meaning created by their ancestors—the connection to art through identity—is powerful. It should be acknowledged. But we should remind ourselves of other connections.

One connection—the one neglected in talk of cultural patrimony—is the connection not through identity but despite difference. We can respond to art that is not ours; indeed, we can only fully respond to “our” art if we move beyond thinking of it as ours and start to respond to it as art. But equally important is the human connection. My people—human beings—made the Great Wall of China, the Sistine Chapel, the Chrysler Building: these things were made by creatures like me, through the exercise of skill and imagination. I do not have those skills and my imagination spins different dreams. Nevertheless, that potential is also in me. The connection through a local identity is as imaginary as the connection through humanity. The Nigerian’s link to the Benin bronze, like mine, is a connection made in the imagination; but to say this isn’t to pronounce either of them unreal. They are surely among the realest connections we have.

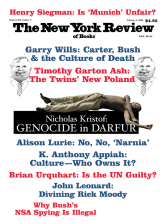

This Issue

February 9, 2006

-

1

I owe a great deal to the cogent (and cosmopolitan!) outline of the development of the relevant international law in John Henry Merryman’s classic paper “Two Ways of Thinking About Cultural Property,” The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 80, No. 4 (October 1986), pp. 831–853.

↩ -

2

James Cuno, “US Art Museums and Cultural Property,” Connecticut Journal of International Law, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring 2001), pp. 189–196.

↩ -

3

See www.theartnewspaper.com/news /article.asp?idart=7995; Carla Power, “Saving the Antiquities,” Newsweek, May 14, 2001, p. 54.

↩ -

4

Carlotta Gall, “Afghan Artifacts, Feared Lost, Are Discovered Safe in Storage,” The New York Times, November 18, 2004.

↩ -

5

Merryman, “Two Ways of Thinking About Cultural Property,” p. 852.

↩ -

6

The quotations from the Daily Telegraph, London Times, and New York Herald, as well as the information about Osei Bonsu, are all from Ivor Wilks, Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order (Cambridge University Press, 1975), pp. 200–201.

↩