In Black Manhattan, Johnson, a distinguished poet and NAACP field secretary, looks back on the early 1900s as a time of change and progress for blacks in New York, in spite of the riot, partly because black musical theater had entered a dynamic, innovative phase. Around the turn of the twentieth century, the traditional minstrel show, a loosely structured comic revue of performers arranged on stage in a semicircle, was replaced by musical farces with connected story lines, works written, produced, and performed by black companies. Johnson and his brother, the composer J. Rosamond Johnson, were a part of this new generation of black musicians, lyricists, and actors, a generation that also included Bert Williams and George Walker, who, in that first decade of the twentieth century, became the most famous black entertainers in the world. They had teamed up in California in 1893, came to New York in 1896 as “Two Real Coons,” and two years later were making a dance called the cakewalk all the rage. Williams and Walker, as they were then known, made American theatrical history by bringing the first black musical, In Dahomey, to Broadway in 1902. West 53rd Street was by then the center of black life in the city, but the move to Harlem was already underway.2

While Walker, the straight man, the dandy of the pair, sang, jigged, and shone, Williams, the clown, danced more slowly in oversized shoes, pulled sad faces, and seldom failed to bring down the house. He wore white gloves and he appeared in blackface. “He has had few equals in the art of pantomime,” Johnson says, and “in the singing of a plaintive Negro song he was beyond approach.” Historians of black theater say that he perfected and then subverted through his sensitive and refined style the minstrel tradition in which he performed. But the enormous popularity of Williams and Walker was as short-lived as that of West 53rd Street or the fashion for ragtime. Bert Williams died in 1922, but his partnership with George Walker had ended in 1909, when Walker’s broken health forced him to retire. Williams tried to keep their theatrical company going on his own—the Williams and Walker company had been the largest and strongest black group of its day—but soon gave up. In 1910 he joined the Ziegfeld Follies, a move Johnson calls Williams’s “defection” to the white stage. Other figures important to the new black theater also fell ill or died around this time, Johnson explains, and what had seemed so alive went quiet.

By the time the black musical theater revived in the 1920s, during the Negro Awakening, there was farce without blackface, even though minstrelsy would continue to be a convention of mainstream popular entertainment and dramatic art for some time—those lascivious black Reconstruction politicians in D.W. Griffith’s 1919 Birth of a Nation are played by white actors in blackface; the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, released in 1927, features Al Jolson in blackface; Ethel Barrymore appeared in blackface in a drama on Broadway in 1932; and in 1933 Lawrence Tibbett blacked up to sing in Louis Gruenberg’s The Emperor Jones at the Met. (The last blackface troupe in England disbanded in 1978.) But minstrelsy in general belonged to a more primitive time, as though World War I separated modern urban American life from the viciousness and innocence of the rural nineteenth century. And yet Bert Williams had been such a star in his time, he was never entirely forgotten, not even in the militant Sixties.3 In an essay written shortly after he died, the Harlem Renaissance novelist and Crisis editor Jessie Fauset set the general terms of how his career has been interpreted:

By a strange and amazing contradiction this Comedian symbolized that deep, ineluctable strain of melancholy, which no Negro in a mixed civilization ever lacks. He was supposed to make the world laugh and so he did but not by the welling over of his own spontaneous subjective joy, but by the humorously objective presentation of his personal woes and sorrows. His rôle was always that of the poor, shunted, cheated, out-of-luck Negro and he fostered and deliberately trained his genius toward the delineation of this type because his mental as well as his artistic sense told him that here was a true racial vein.4

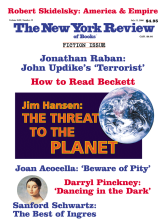

Dancing in the Dark, Caryl Phillips’s haunting novel about the career of Bert Williams, challenges the view that Williams’s black audience appreciated that he was trying to transcend the racial stereotypes of the day.5 Most of Phillips’s characters were real people and he recreates the defiant mood at the Marshall Hotel when it was the unofficial headquarters for the young stars of the new black theater, such as Will Marion Cook, the composer of In Dahomey, Jesse A. Shipp, who wrote the book, and the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who wrote the lyrics, and where they “squabble over the virtues of the cakewalk, and [over] which theaters a colored performer ought best to avoid, and whether coon songs really do bring down the race.”

Advertisement

In his exploration of racial consciousness in the vaudeville era, Phillips intersperses real and invented documents throughout—song lyrics, interviews, white and black newspaper accounts, and Buster Keaton’s testimony about how his father broke the rules to drink with Bert Williams in the black section of a Boston bar. Moments from Williams and Walker’s stage shows give an impression of what their comedy was like, but Phillips’s story is concerned primarily with Williams’s inner life. He constructs his novel, mostly in the third person, but sometimes in bravura first-person passages, by looking at Williams and the cultural twilight he belonged to from several points of view—those of his partner, George Walker, his wife, Lottie, Walker’s wife and fellow performer, Ada Overton, Jimmie Marshall, the black proprietor of the Marshall Hotel on the then-fashionable West 53rd Street, and even Williams’s father, set up by his son with a Harlem barbershop. They wonder about him, and, as the novel progresses, about the ways in which he subtly changes, declines.

2.

In Phillips’s work, no one broods about Bert Williams more than Williams himself. Born Egbert Austin Williams in the Bahamas in 1873, the successful young actor, whose strict father was ashamed of him because of the black clown he was paid a fortune to portray, will be a stranger to the faded gentleman who drinks by himself in the afternoon dark of a Harlem bar. “The funniest man I ever saw and the saddest man I ever knew,” W.C. Fields famously said of him. It is 1903 when the novel opens; Bert is at the height of his fame, playing Shylock Homestead in In Dahomey on Broadway, but “his heart is heavy with shame.” His routine of filling himself with the “grandeur of whiskey” before a performance is also well established. The use of blackface, of cork makeup, is at the heart of the question he asks about the worth of his career, the technical perfection of his mask an achievement he’s not sure means as much to either the blacks or the whites in his audience as it does to him.

Back in 1893, when trying to scratch out a living in the Barbary Coast section of San Francisco, Bert and George Walker worked without blackface makeup, which angered most theater owners. They were tired of “trying to be something other than the colored monkeys,” and of “having to look up to the colored people in the upper balcony and silently beg their forgiveness.” But it was a promise they could not keep. Bert remembers standing before a mirror in Detroit in 1896: “As I apply the burnt cork to my face, as I smear the black into my already sable skin, as I put on my lips, I am leaving behind Egbert Austin Williams.” Every night he disappears and has to recover himself before he leaves the theater. George dislikes his partner blacking up to play the clown, but he admits that when Bert turned himself into a “coon,” they started to make money. Williams and Walker are popular with blacks at first just because they are stars, ambassadors of the race, and have even performed on the lawn at Buckingham Palace for the little Prince of Wales.

Williams and Walker are credited with being the first to throw off some of the conventions of minstrelsy, starting with the familiar plantation settings. They were criticized by the white press for not having a real coon song in their show In Dahomey, and for omitting the cakewalk finale that had become part of the formula of the minstrel show. (In the end, they gave in and restored this popular feature.) They introduced into their plots what Walker called “the native African element.” The title of and idea for In Dahomey—black crooks try to persuade an elderly rich black man in Florida to finance a back-to-Africa scheme—came from their experience of meeting Africans in the San Francisco Exposition of 1893, and this encounter has become a highly symbolic moment in African-American cultural history. When the Dahomeyans who had been engaged to appear in an exhibit at the fair didn’t arrive, American blacks, including Williams and Walker, were hired to play their parts. Once the real Africans got there, Williams and Walker stayed on to study them. The black African met the black West Indian and the black American and they misunderstood one another.

In Phillips’s novel, Bert Williams is very much the observer, the one peering out from behind his makeup at white audiences, secure in the knowledge that he can manipulate them, so long as he respects their potential for violence. However, when the manager of the 1893 exposition tells Bert and George and the six other blacks who are paid to dress in animal skins that the Africans they have been impersonating are for various reasons unsatisfactory and are being sent back without pay, Bert is so busy feeling sorry for them that he is unaware of the possibility that they may be judging him:

Advertisement

The man from Dahomey looks at the Chinese lettering that has been painted on to Bert’s face, and at the small Swiss bells that are strung together on a fraying piece of string and tied loosely around his ankles, but he says nothing to the American man about this costume. So this is America standing tall and proud before him. It never crosses his mind that this bizarre-looking man could possibly be representing Africa, let alone Dahomey, and against his better judgment the African begins to feel sorry for Bert.

And yet one of Williams’s most treasured books is John Ogilby’s Africa, published in 1670, which he turns to often,

for proof that Africa was a continent of history and tradition, and not one of rude chaos; and the act of entering this book always enabled Bert to experience the temporary peace of being able to moor himself in some other place.

The pressures of success strain the Williams and Walker partnership. After a successful tour in England in 1903 and 1904 with In Dahomey—their wives also starred in the show—George wants to find another black show rather than return to the crude vaudeville circuit. While George is impatient of the future, Bert is plagued by doubt.

In Dahomey tours the US throughout 1905, but by 1906 the actors are feeling beleaguered. A lawsuit against their white promoter has made their enormous yearly earnings public. The judge “gasped” when he read out the figures in court. Abyssinia, their new show, which does without “the razors, the chickens, the loose women, and the low talk of regular coon performances,” and offers instead over one hundred performers and spectacular lighting effects, is not the hit In Dahomey was. It fails to please critics because “it contains far too little of the colored coon.” George had hoped for an artistic breakthrough with Abyssinia, prompting Bert to remind him that if whites are paying then they must give them what they want. But his partner refuses to accept that they aren’t impresarios tackling in Abyssinia the serious theme of African heritage, that their company isn’t “a race institution” nurturing black talent and changing the American stage.

Professional pressures have an adverse effect on Bert’s private life as well. No sooner is he married to Lottie than he withdraws from her. Her marriage is unsatisfactory, but her pride won’t let her commiserate with her friend, Ada, George’s wife. Ada, on the other hand, knows she will have to learn to ignore her husband’s indiscretions. It isn’t like him to get stuck on one woman, but when he embarks on a torrid affair with Eva Tanguay, a salty white entertainer known in theatrical history as the “I Don’t Care Girl,” Ada takes morphine and is rushed to the hospital.

Sometimes in Phillips’s novel, George upstages Bert. Because he is the more extroverted of the two, womanizing, up all night talking and drinking with other black actors and musicians, more can happen to him in the way of incident. Moreover, George anticipates the flamboyance of the Jazz Age and his impatience and resentments as a black in show business are readily understood. It was George who was beaten during the New York riot of 1900, shortly before they opened in Sons of Ham.

In the novel, Bert’s father never gets over his son’s having chosen the stage over Stanford University. The superiority that Bert Williams was said to have felt as a Caribbean-born black isn’t really touched on in Phillips’s novel, although his formality of manner, his West Indian reserve, could be said to stem from his disdain for US American blacks. Phillips portrays him as aloof, distant from other blacks, living largely in his head, incommunicative, introspective, and passive once offstage. But even when onstage he is all reflection, carefully studying how to improve their act. (“I took to studying the dialect of the American Negro, which to me was just as much a foreign dialect as that of the Italian,” Williams once said in an interview.)

Dancing in the Dark moves gingerly through the likely effects of this particular time in America on the sensibilities of someone as sensitive to those around him as Bert, this quality of being attuned to others the secret of his success as a mimic. Meanwhile, the partners begin to drift apart because of their differences over how to overcome the limitations imposed by racism. In their new production, Bandana Land, “Bert’s queer clothes and quaint colored humor contrasts bizarrely with the bejeweled opulence of George’s vision.” But in 1909, George, who got his start in San Francisco when he stole a banjo from a sleeping man, has a stroke after a performance, a complication from syphilis, “Jack Johnson fever” or “the entertainer’s disease.”

On his own, Bert Williams is increasingly self-conscious about his blackface character at a time when Jack Johnson is heavyweight champion of the world and race pride is “rising everywhere.” In a dramatic scene after Bert has joined the Ziegfeld Follies, James W. Nail, a leading black Harlem realtor and James Weldon Johnson’s father-in-law, harangues Bert as part of a delegation of influential black men petitioning him to cast aside his “nigger coon” impersonation. Bert tries to tell them that his colored man was more than a “gin-guzzling, crap-shooting…nigger”:

He suffers. Our compassion goes out to him. He shuffles a little, and he may be slow-witted, but we surely recognize this poor man. The essence of my performance is that we know and sympathize with this unfortunate creature. Eventually his feverish thoughts stopped racing around his mind, but he could still find no polished words or phrases to share with this delegation, and so he calmly finished his tea and looked from one handsome face to the next.

In 1919, after nine years with the Ziegfeld Follies, Bert decides that “it is time to step back and away from his own reflection and save himself.” He realizes that his is “a face that was put in place in the last century but that, in this new century, no longer makes much sense to either white or colored.” The space behind the mask, to borrow a phrase from current academic theory about the “politics of representation,” is a lonely prison. He was a success, but perhaps he wasted his talent, the novel seems to be saying.

Dancing in the Dark is almost reluctant to put a label to the hurt, or to make a display of Williams’s vulnerability. Phillips places the emphasis on Bert Williams’s dignity in his “performative bondage,” because although he had an interest in recording that Walker did not, and he also made five films, meaning that even today his voice can be heard and his pantomime seen, his comic style isn’t really reclaimable, in the way that as time goes by the pathos of Charlie Chaplin comes through more than what was supposed to have been funny about him.6 In a prologue about how Harlem has changed since Bert Williams walked its streets, Phillips makes us aware that not even the Harlem Renaissance was Bert Williams’s time. His and Walker’s frustration as pioneers of black theater is a constant theme in the novel, but the pride and intelligence with which they coped are what Phillips pays homage to, and not so much the community of laughter, the “sense of cohesion” that laughter gives. In Phillips’s novel, Bert Williams, proud to be inducted into a Masonic lodge in Edinburgh, is far from being a folk figure. Phillips’s characterization of Williams as a man incapable of revealing himself fully to anyone else somehow fits with the atmosphere of his five other novels, all of which concern specific episodes in transatlantic black history. They are not at all autobiographical. Caryl Phillips’s life is not on display in his work, only his intelligence and his careful, cold prose.

It is interesting to read Dancing in the Dark, about the last days of black minstrelsy, in conjunction with Wesley Brown’s memorable, highly original novel of some years ago about its beginnings, Darktown Strutters.7 Brown gives Jim Crow, whose song the white performer Thomas Rice has overheard and then made famous, a son, also called Jim Crow. He becomes a remarkable dancer with Rice’s carnival troupe just before the Civil War. If Bert Williams found it impossible to conceive of himself as a black performer without blacking up, then the young Jim Crow stubbornly refuses to apply burnt cork, even though hostile audiences make it clear that they want to see darkies when they go to a show and “not some uppity nigger who think he too good to act the coon like he supposed to!” A white colleague tells him that he could beat them at their own skin game if he did wear the makeup, “cause while they tryin like the devil to hate you for what you are, your face is makin em laugh at what you ain’t.”

When Jim doesn’t run away from the troupe, a black woman asks if he wants to be free or to be seen. “For me to be free, I gotta be seen. I can’t hide out.” More experienced performers caution Jim that so long as blacks know what they’re doing, it doesn’t matter what white people think and that to live in a country where there is so much hate means he risks turning away from the power inside him and wasting his time wanting the power others have over him. In one scene, a group of whites in blackface intent on teaching Jim Crow a lesson battle with members of the troupe, who are still in blackface themselves. In the melee, no one can tell who is on which side, and no one wants to let someone else wipe off his makeup to find out.

Brown’s brilliant first novel, Tragic Magic (1979), established him as Ralph Ellison’s heir, and the beautifully written Darktown Strutters makes a very Ellisonian point about how culture in America has been preserved, shared, and transmitted across regional and racial lines. Thomas Rice himself is described as a man who needs to be on a stage in blackface, otherwise he has no idea who he is, because as a homosexual he is not one of those white men who “do a lotta damage tryin too hard to be white.” His Non-Pareil Minstrel Show is racially mixed and when he is murdered onstage by a white man in the audience, the company is taken over by two black women who are also lovers. The sight of blacks and whites together and in blackface onstage is intolerable to the communities of the upper South and Midwest that they tour in the aftermath of the Civil War. The mob that will destroy them is incited with stories of how the troupe’s members

not only carried on their race-mixing and sex-switching among themselves, but the one called Jim Crow sang a song that told how this blasphemy started in a place called Paducah and how they were going to mongrelize the whole country with their foul and filthy ways!

Jim Crow survives the furious attack and eventually slips off, into myth, as it were. But so much of his life has been destroyed that this doesn’t feel like a victory.

Black minstrelsy has always been understood as an appropriation, the black man poking fun at himself and especially at the white man, and black minstrel shows were always regarded as “more authentic” than the white burlesques from which they originated. But nowadays black minstrels are not seen as black performers trapped into humiliating roles, but as black performers helping to define what blackness was.8 Karen Sotiropoulos, in her extremely useful history, Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the Century America,9 argues that the popular stage was a part of political debate, and that In Dahomeyhad an “anti-imperialist” message. In his recent study, The Last “Darky”: Bert Williams, Black-on-Black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora, Louis Chude-Sokei looks at minstrelsy in the context of the vogue for turning Africa into a series of ethnographic displays, such as the San Francisco exhibit.10

The aesthetics of the minstrel stage not only enabled whites to fantasize about blacks, it also helped blacks to define themselves in opposition to whites. Chude-Sokei quotes from remarks Williams made in an article in 1918, “The Comic Side of Trouble,” in which he says that he finds his material by knocking around in out-of-the-way places and listening. “Eavesdropping on human nature is one of the most important parts of a comedian’s work.” One of his most famous routines, The Poker Game, which was captured on film, Williams was said to have developed after watching a mental patient play an imaginary card game. What Chude-Sokei finds interesting about Williams’s remarks is his stress on being the spectator, his appropriating for himself the “narrative power” of the viewer, rather than thinking of himself as the viewed, under the scrutiny of whites. Maybe Dancing in the Dark, much like Darktown Strutters, shows that as academic theorists become ever more triumphalist concerning the elevation of vernacular culture, the black novelist as alternative historian is free to return to the nobility of defeat as a grand theme.

This Issue

July 13, 2006

-

2

See Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto: Negro New York, 1890–1930 (Harper and Row, 1971). Osofsky also gives a somewhat different and more authoritative version of the riot of 1900.

↩ -

3

See Loften Mitchell, “I Work Here to Please You,” in The Black Aesthetic, edited by Addison Gayle Jr. (Doubleday, 1971), p. 297.

↩ -

4

Jessie Fauset, “The Symbolism of Bert Williams,” reprinted in The Crisis Reader, edited by Sondra Kathryn Wilson (Modern Library, 1999), p. 255.

↩ -

5

There have been a number of biographies of Williams. See Ann Charters, Nobody: The Story of Bert Williams (Macmillian, 1970) and Eric Ledell Smith, Bert Williams: A Biography of the Pioneer Black Comedian (McFarland and Company, 1992).

↩ -

6

Although one of Bert Williams’s short monologues appears in Hokum: An Anthology of African American Humor, edited by Paul Beatty (Bloomsbury, 2006), which suggests that he still appeals to some.

↩ -

7

Cane Hill Press, 1994.

↩ -

8

Amiri Baraka says in Blues People (William Morrow, 1963), “I find the idea of white minstrels in blackface satirizing a dance satirizing themselves a remarkable kind of irony.” In his monumental To Wake the Nations: Race in the Making of American Literature (Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 1993), Eric J. Sundquist contends that “the capacity to define the behavior of ‘real coons’ was nothing less than the capacity to take control of one’s culture, one’s ancestral history, and one’s racial identity.”

↩ -

9

Harvard University Press, 2006.

↩ -

10

Duke University Press, 2006.

↩