1.

When Sergey Prokofiev fled Soviet Russia for the United States in 1918, among the other papers, manuscripts, and scores he left behind in Petrograd were the diaries he had kept for the past eleven years. The young composer was a seasoned diarist. As Anthony Phillips writes in an introduction to his new translation of the early diaries, on his twelfth birthday, in 1903, his mother had presented him with a thick, handsomely bound notebook, telling him to “write down in this everything that comes into your head”; for the next thirty years Prokofiev complied, filling his notebooks with vivid observations, musical reflections, and insights into personalities, often all the better for being trivial. He stopped writing diaries in 1933, when he began to prepare for his permanent return to Stalin’s Russia, where such records could be dangerous.

Prokofiev’s earliest diaries have been lost. But those from 1907 on were miraculously saved, some by the composer’s mother, who brought them out of Russia when she fled to France in 1920; others were hidden in Petrograd by his friends, including the conductor Sergey Koussevitzky and the composer Nikolay Myaskovsky. Prokofiev first returned to the Soviet Union on a concert tour in 1927, at which point he retrieved the diaries that were still there and took them to the United States. When he returned to Russia in the 1930s he put all his diaries in a US safe, where they remained until his death in 1953. In 1955, they were transferred, with his family’s consent, to the Central (Russian) State Archive of Literature and Art in Moscow, with access denied to all but the composer’s direct heirs for the next fifty years. But as his son Sviatoslav Prokofiev explains in his foreword to the diaries, after 1991 the family decided to publish them. Preparing the text for publication was a painstaking task of deciphering, according to Sviatoslav Prokofiev, because from 1914 onward, the composer started to employ “a system of writing down words with the vowels eliminated”:

Thus, for example, “chmd” for “chemodan” (suitcase); “snchl” for “snachala” (at first); “rstrn” for “restaurant”; “udrl” either for “udral” (did a bunk) or “udaril” (hit) and so on…. Our most difficult task was to decipher unfamiliar names, and this often entailed exhaustive researches.

The diaries are a revelation. No other composer wrote so much about himself. In 1,700 densely printed pages they provide an intimate and candid portrait of the artist as a young man that is radically different from the public image he presented in his autobiography, written at the height of Stalin’s terror in 1937.1 The hero of Prokofiev’s autobiography is passionate and serious, full of confidence in his talent, even arrogant; but in the diaries he comes across as awkward, shy, and insecure, despite his frequent boasting of his success. There is not much self-reflection in the diaries. “I am mostly setting out the facts, describing the day as it goes on from the morning through to the evening,” Prokofiev admits. The diaries’ strengths are their lively prose and clarity, their capacity to recreate the atmosphere of place and time, and their flair for dialogue—qualities that Anthony Phillips has happily maintained in his excellent translation. This literary talent is the other revelation of the diaries. As Prokofiev concluded in his diary on November 23, 1922: “Had I not been a composer, I would probably have become a writer or poet.”

Prokofiev was born in 1891 on the family’s estate in Sontsovka, a remote settlement on the Ukrainian steppe, where his father was an agronomist. The boy’s mother was the driving force behind his early musical career, instilling in him from an early age a belief in his destiny to become a composer. An amateur pianist who craved city life, she left her husband behind when she took her son to Moscow to study composition with Reinhold Glière, and then followed Sergei to the Russian capital, where, at the age of just thirteen, and still wearing shorts, he was the youngest student ever to enroll in the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov, its senior professors, were astonished by the talents of the young prodigy, who already had four operas to his name. Here was the Russian Mozart.

The Prokofiev of the early diaries is a curious mixture of musical maturity and social childishness. At the age of sixteen, he is streaks ahead of his fellow students in composition, harmony, and theory, but still playing with teddy bears. He is shy among the girls, who outnumber the boys in the class for general education by seventeen to three, and although in time he revels in their company collectively, and even keeps a list to order them by preference, he feels a stronger attraction to beautiful young men. There is a romantic friendship with a music student called Max Schmidthof, who shares his passion for verbal sparring, travel, chess, fast cars, and expensive clothes. Max committed suicide in 1913, just before Prokofiev completed his Second Piano Concerto, which he dedicated to his friend. In 1979, Prokofiev’s wife Lina was asked about their friendship by Harvey Sachs, who questioned if Schmidthof had been homosexual. She told Sachs that the Chess Club, to which the two men had both belonged, allowed “the possibility of having multi-tastes,” and that, while he never talked about such things, Prokofiev had “had such tendencies.”2

Advertisement

Prokofiev’s character emerges clearly in the pre-war diaries. Obsessively methodical, he makes lists of everything: compositions, marks in class, moves and scores at the Chess Club. Every aspect of his life is ordered and purposeful. At the age of nine, he tells us, he was “writing histories of the battles fought by my tin soldiers, keeping track of their losses and making diagrams of their movements.”3 Later, he reads fiction, but only to discover texts for his music, and biographies of composers to learn how to emulate their achievements. He keeps every letter he receives and drafts or copies of the letters he has sent, arranging them chronologically in bound volumes. He is constantly at work on his own archive. “In the afternoon,” he writes on July 18, 1914,

I rooted through all the drawers in my desk and the cupboards selecting what I planned to put in the fire-proof box: diaries, bound volumes of letters and letters that were still loose, music manuscripts, the “Yellow Book”4 and other such documents. The result was a huge pile, enough to fill a whole trunk.

Sometimes Prokofiev slips into the mode of autobiographical writing, switching from the real-time observation of events to an account of the past, as if charting his own life from the perspective of some future point in time, when he will have joined the pantheon of “great composers.” This tendency is particularly marked in the entries for 1911–1912, when he had barely entered his twenties—a time, he writes in the preface to his autobiography, when

having read Rimsky-Korsakov’s Record and a long biography of Tchaikovsky, and feeling that I was a composer in whom people were beginning to take an interest, I decided that in time I would write my autobiography. Someone had said in my presence: “I would compel all remarkable people to write their autobiographies.” I thought, I already have the material. All I have to do now is to become famous.5

Ambitious and competitive, Prokofiev is always thinking in his diaries about what he needs to promote his musical career. Success and recognition are everything to him. Forced by his father to take his diploma in composition theory two years earlier than necessary, the young composer bitterly regrets that he is thus deprived of the opportunity to improve his final marks and win a medal, and sulks at the awards ceremony in May 1909:

They read out my name from the stage and called me up to be formally presented with the piece of paper, but I did not go up—where would be the pleasure in that without the medal?

Prokofiev sees himself as “temperamentally easy-going” and quick to make friends, but others regard him as a prickly character, immature and arrogant, as revealed by a student’s pen-portrait that he cites in his diary on September 30, 1913:

Although he has some savoir-faire

His manners often let him down;

A childish streak is sometimes there

When he squires ladies round the town.

His tongue is not at all averse

To scorching people with a curse,

But woe betide the man who tries

To do it back to Serge: he dies.

Prokofiev is “not much given to soul-searching,” as he himself admits. He lacks self-awareness at this stage. Emotionally he seems detached, and perhaps a little cold. On the death of his father, in July 1910, he writes in his diary:

Did I love him? I do not know. Were anyone ever to insult or do him harm, I would have gone to any lengths to defend him. As for loving him, in the past six years I had grown away from him. We had little in common.

Fourteen years later, when his mother died, a far more central figure in his life, Prokofiev only writes: “Mother died in my arms at 12.15 am.” And not another word. For a year he concealed her death, making up excuses for her “poor health” in his correspondence with friends and relatives, ostensibly because he did not want to burden them with the sad news, but perhaps too because he couldn’t deal with the issue.

2.

The Conservatory was the center of musical life in St. Petersburg, a city in the vanguard of the cultural revolution that transformed all the arts in Europe in the years before the outbreak of World War I. Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov were bastions of the Russian nineteenth-century musical traditions in the Conservatory, while Anatoly Lyadov continued to compose in his own languorous style of Russian folk-inspired musical impressionism, but modern European trends were being introduced and radically transformed at a dizzying rate by their students—young composers such as Nikolay Tcherepnin, Myaskovsky, and Igor Stravinsky—whose music was increasingly rich in dissonance, and tonally and rhythmically unorthodox.

Advertisement

Among these, Prokofiev was most directly influenced by Tcherepnin, the composer of Le Pavillion d’Armide, the curtain-raiser to the 1909 saison russe in Paris, and (until he withdrew from the project) the man originally intended by Sergey Diaghilev to compose the music for The Firebird.6 Prokofiev attended Tcherepnin’s conducting class at the Conservatory and Tcherepnin encouraged him to develop the neoclassical style which became the hallmark of Prokofiev’s early works, from the Sinfonietta of 1909 to the First (“Classical”) Symphony of 1916–1917.

The influence of Petr Tchaikovsky—a sort of patron saint to the Russian music world long after his death in 1893—is another revelation of the diaries. Tchaikovsky was the model of the “great composer” which the young Prokofiev aspired to become. In 1913, Prokofiev took five months to read and study a biography of the Russian composer (presumably the three-volume life by his brother Modest Tchaikovsky7 ). He took inspiration from Tchaikovsky’s life, his speed of composition, and from the “stunning beauty” and “emotional power” of his music, the Sixth Symphony in particular. In emulation of its qualities, he strove to introduce a “simple and transparent” style to the orchestral accompaniment of the Second Piano Concerto, which he was then finishing.

An early breakthrough for the young Prokofiev was an invitation to the Evenings of Contemporary Music, a society for the promotion of new composers, in 1908. The Evenings launched a number of important musical careers, including those of Myaskovsky and Stravinsky, and it was through that concert series that Prokofiev became known as a composer outside the Conservatory. Financial pressures following the death of his father made it all the more important for Prokofiev to get his music published and performed—a struggle that, despite his later fame, would continue throughout his life and is well documented in the diaries. His Piano Sonata, opus 1 (1909) and Four Etudes for Piano, opus 2, from the same year, were both rejected by the Russian Music Editions, run by Koussevitzky, at that time influenced by his consultant composers, Nikolai Medtner and Sergey Rachmaninov, who, according to Prokofiev, “turned down everything that had the slightest hint of novelty.”8

Prokofiev was equally frustrated by the opposition of Glazunov, an arch-conservative, who became the dominant figure in the St. Petersburg Conservatory following the death of Rimsky-Korsakov in 1908. “It being now clear that I could not expect my works to be performed at the Conservatoire, I began to look for other avenues and other contexts,” Prokofiev wrote in his 1911 diary.

I reasoned as follows: if I made a list of all the well-known Petersburg conductors (there are five), collected together all my scores (there are also five of them) and showed my five scores to the five conductors I would end up with 5 x 5 = 25 chances that one of them might get performed. Surely my compositions cannot be so bad that out of twenty-five attempts not one will get anywhere?

Prokofiev hoped to get in with Diaghilev, whose saisons russes were taking Europe by storm. He had “all kinds of fantasies about creating a ballet for Paris and the European fame that would follow.” In 1914, he even went to London in the hope of winning a commission from Diaghilev. But the outbreak of the war put an end to such thoughts.

The climax of the first volume of Prokofiev’s diaries is a fascinating account of the composer’s triumph in the prestigious Rubinstein Prize, the piano competition for students graduating from the Conservatory, with a performance of his Second Piano Concerto, in April 1914. It was the only occasion in the history of the St. Petersburg Conservatory that a student graduated with a performance of his own concerto. Prokofiev was a virtuoso pianist. In his earlier exam recital, he had given a brilliant performance of the Schumann Sonata No. 1 in F sharp minor in which he had managed to break a string, which “flew out of the piano and into the audience.” Glazunov, who detested the concerto, was against allowing Prokofiev to perform it in the competition’s final round; but in the end the judges ruled that Prokofiev should play the grueling Tannhäuser overture before his own concerto. Prokofiev scored a success, winning the support of thirteen of the twenty-one judges. “Glazunov was so distressed by the result that he did not want to announce it,” the young composer noted in his diary. But as the director of the Conservatory, Glazunov was forced to tell the waiting crowd that the prize had been awarded to Prokofiev for the performance of the concerto.

3.

The diaries come alive when Prokofiev is writing about chess. Prokofiev was a chess enthusiast—as were many other musicians at the Conservatory, where games were often played in the intervals between rehearsals and concerts. Scriabin, Rachmaninov, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov were all keen chess players. In 1907, Prokofiev joined the club at Nevsky 55, one of the first chess clubs in St. Petersburg, where he was among the best players. His heroes at that time were the world chess champion Emanuel Lasker and the Russian champion Akiba Rubinstein, who shared top prize at the first major international competition in St. Petersburg in 1909. But five years later, when the city played host to a bigger International Tournament, his new idol was the dashing Cuban genius José Capablanca, to whom by temperament he was naturally drawn.

Like Prokofiev, Capablanca was an infant prodigy (legend has it that he learned the rules of chess at the age of four by watching his father play and then beat him in their first game). By the time of his arrival in St. Petersburg as an attaché of the Cuban Foreign Office in 1914, the twenty-five-year-old was a superstar in the chess world, renowned for his fast and direct style of virtuoso play. The International Tournament was his first real chance to pit his strengths against Lasker, whose style of play was more complex and methodical (Prokofiev compared the “profound Lasker to the mastery of Bach” and the “lively Capablanca to the young Mozart”9 ).

Prokofiev attended every major match of the International Tournament, literally running between the Chess Club and the Conservatory, where the piano competition was simultaneously moving toward its own climax. On April 8, after practicing his concerto for an hour and a half, he ran from the Conservatory to catch the opening round of the tournament at the Chess Club:

At the barrier erected in front of the playing tables stood a crowd several rows deep (growing eventually to five rows, with many people standing on chairs). To go through the barrier one had to pay a charge of 5 roubles, which I did. At two o’clock the bell went and the masters took their places. I positioned myself at Lasker’s table, where old man Blackburne, who had drawn Lasker in the first round, made his first move. Instead of replying, Lasker stood up, strolled indifferently round the room, then returned to the table, moved his pawn and dinged the bell. The great tournament has begun. At the next table Nimzowitsch is playing Capablanca. Capablanca has twice before defeated him, and now plays with a quick, easy elegance. Nimzowitsch cunningly deploys his queen to threaten a pawn, which Capablanca casually sacrifices. General astonishment. In the next room, where a heated discussion of the match is going on, everyone is arguing and shouting, but the consensus is that Capablanca has made a mistake in giving up his pawn, he can gain no advantage from it and even if he can, it is not enough.

But soon Capablanca goes on the attack, and “confounding the expectations of all the St. Petersburg pundits,” not only wins back a pawn from Nimzowitsch but fights him into a corner:

Nimzowitsch sits in dismay, hunched over the board, visibly losing his head. Capablanca in complete contrast impresses by the insouciance of his play: getting up all the time to see what is going on in other matches, wandering about the hall laughing.

Capablanca was defeated by Lasker, who finished in first place, half a point ahead of him, but it was the style of the Cuban’s play that had won the hearts of young chess fans. After the tournament, Capablanca played three times against Prokofiev during exhibition games on thirty tables simultaneously. The speed with which the Cuban played and his extraordinary ability to see the situation instantaneously made him one of the best simultaneous players in the history of chess. In their first game Prokofiev was undone by Capablanca’s speed, especially toward the end of the second hour, as other players lost and only five or six remained in play. In the second, Prokofiev also lost: his attempt to put the Cuban into check by returning pieces back to a previous position was immediately noticed by his opponent, who “burst out laughing” and proceeded to show him how he “would have been able to win in precisely the same way from that check as well.” But in their final game, on May 16, Prokofiev laid a trap, forcing Capablanca to sacrifice a piece, and then pressed home his advantage to score a precious victory. Capablanca was visibly exhausted, having gone to bed at eight o’clock that morning and gotten up at noon, so perhaps he was not at his best.

In 1918, Prokofiev and Capablanca met again in New York. The two touring virtuosi became life-long friends. They were similar in disposition, outlook, taste, and style: they liked fine clothes, fast cars, and gambling; they were both international celebrities and internationalists (they married women of each other’s nationality); and they shared a fascination for each other’s art.

Prokofiev’s affinity for chess was perhaps connected to his extraordinary capacity for ordering details in his mind. In his diary on November 4, 1913, he describes a remarkable technique he developed to memorize music:

When a piece has been sufficiently learned with the music, one must try to remember it away from the piano, imagining the sound of the music in parallel with the way it is written, that is to say recalling the music through the ears at the same time as remembering how it looks to the eyes. This must be done slowly and meticulously, reconstructing in imagination every detail of every bar. This is the first stage. Stage two consists of recalling all the music aurally while training the visual side to recall not the score but the keyboard and the individual keys which are employed to produce the sound of the music in question…. The more one gradually succeeds in absorbing into memory the keyboard alongside the music, the more one can be sure that the piece is irrevocably stored in the memory, since when it is reproduced all three sorts of memory are combined: musical, visual and digital, each of them having first been exercised separately and only later integrated…. A practical advantage is that one can practise anywhere at any time: walking along the street, sitting in the tram, waiting in a queue, anywhere indeed where one would be bored without this activity to engage the mind.

It is said that the nineteenth-century American chess master Paul Morphy (another infant prodigy) was able to memorize any piece of music after hearing it a single time; he had the same ability with chess, remembering games he had seen only once. Music, chess, and memory are closely linked, it seems. As Capablanca wrote in 1922, one year after becoming the world chess champion:

The memory of chess experts is like the memory of the great musicians. Just the same as a great pianist, for instance, can sit down and play for hours without looking at the score of any of the works he plays, a chess master can go through endless games and variations which he has unconsciously stored in his mind. The great musicians see the notes in the minds’ eyes as though they were in front of them. In just the same way the chess master sees the moves and positions…. In fact, it should be noticed that there must be some analogy between the minds of a musician and a chess player.10

4.

The second volume of Prokofiev’s diaries, which will appear in English next year, provides a detailed record of the composer’s wandering in emigration and offers new insights into the great mystery of his life: why he decided to return to the Soviet Union at the height of Stalin’s terror in the 1930s.

Prokofiev’s career in the West had not gone as well as he had hoped. In the United States, his experimental style was not much to the taste of the generally conservative music critics and concert-going public, who preferred Rachmaninov, another refugee from Soviet Russia. According to the writer Nina Berberova, Prokofiev was heard to say on more than one occasion: “There is no room for me here while Rachmaninov is alive, and he will live another ten or fifteen years.”11 In 1920, Prokofiev left New York and settled in Paris. But with Stravinsky living there or in Switzerland, the French capital was even harder for Prokofiev to conquer. The patronage of Diaghilev was all-important in Paris, where Russian ballet was in demand. Prokofiev liked to write for the opera, an “out of date” art form according to Diaghilev, and of the three ballets he composed in the 1920s, only one, The Prodigal Son (1929), was a success with the French public.

Isolated from the émigré community in Paris, Prokofiev began to develop contacts with the Soviet musical establishment. He had always kept in touch with friends and relatives in his homeland. In 1927, he accepted an invitation from the Kremlin to make a concert tour of the Soviet Union. On his return to Petersburg he was overcome by emotion. “I had somehow managed to forget what Petersburg was really like,” he wrote in his diary of the trip; “the grandeur of the city took my breath away.” The lavish production of his opera Love for Three Oranges in the Marinsky Theatre made him feel that he had at last been recognized as Russia’s greatest living composer. The Soviet authorities pulled out all the stops to lure him back for good; old friends and allies like the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and the avant-garde director Vsevolod Meyerhold talked of new commissions that might be awarded. Prokofiev had become tired of the years of wandering, of concert tours, and yearned to return to a settled existence that would allow him to compose.

Beginning in 1932, Prokofiev began to spend half the year in Moscow; four years later he moved his wife and two sons there for good. He knew to what he was returning—his diaries show that he was aware of the problems Soviet artists faced—but he thought his music would somehow protect him. For a while his plans worked out. He was afforded every luxury—a spacious apartment in Moscow with his own furniture imported from Paris and the freedom to travel to the West (at a time when Soviet citizens were dispatched to the Gulag for having spoken to a foreigner). With his uncanny talent for writing tunes, Prokofiev was commissioned to compose numerous scores for the Soviet stage and screen, including the music for Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible.

But then his working life became more difficult. Many of his more experimental works were criticized for being “formalist” in the assault on modern music that began with the attack on Dmitry Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in 1936. For example, the Soviet Committee for Artistic Affairs blocked the performance of Prokofiev’s cantata (1936–1937) for the twentieth anniversary of the October Revolution—despite his use of texts by Marx, Lenin, and Stalin—because the work failed to meet their definition of “socialist realism.” After 1948, when the “anti-formalist” campaign was renewed as part of the regime’s clampdown against Western influence, nearly all the music he had written in Paris and New York was banned from the Soviet concert repertory. Prokofiev spent his final years in virtual seclusion. He turned increasingly to chamber music, composing pieces like the Violin Sonata in D Major, which he wrote for David Oistrakh, his oldest chess partner, to whom he once explained that its haunting opening movement was meant to sound “like the wind in a graveyard.”12 Oistrakh played the sonata at Prokofiev’s funeral, a sad affair that was barely noticed by the Soviet public. Stalin died on the same day as Prokofiev, March 5, 1953. There were no flowers left to buy, so a single pine branch was placed on the composer’s grave.

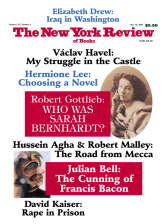

This Issue

May 10, 2007

-

1

Sergey Prokofiev, Avtobiografiia, edited by Miralda Kozlova (Moscow: Sovetskii Kompozitor, 1973; revised with supplementary chapters, 1982). There is a heavily abridged translation, Prokofiev by Prokofiev: A Composer’s Memoir, edited by David H. Appel and translated by Guy Daniels (Doubleday, 1979); further cuts were made for the British edition, edited by Francis King (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1979).

↩ -

2

David Nice, Prokofiev: From Russia to the West, 1891–1935 (Yale University Press, 2003), p. 59.

↩ -

3

Prokofiev by Prokofiev, edited by Francis King, p. xi.

↩ -

4

A small yellow notebook in which he kept the answers by interesting people he had met to the question “What are your thoughts on the sun?”

↩ -

5

Prokofiev by Prokofiev, p. xii.

↩ -

6

After Tcherepnin’s withdrawal, the Firebird commission was offered to Lyadov, who failed to compose anything (he was notoriously lazy), and then to Glazunov, who turned the offer down, whereupon it went to Stravinsky, Diaghilev’s fourth choice.

↩ -

7

Modest Tchaikovsky, Zhizn’ Petra Il’icha Chaikovskogo three volumes (Moscow-Leipzig, 1900–1902).

↩ -

8

S. S. Prokofiev: Materialy, dokumenty, vospominaniia, edited by Semyon Shlif-shtein (Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Mu-zykalnoe Izdatel’stvo, 1956), p. 143.

↩ -

9

Yurii Sviatoslav, S. S. Prokof’ev i sha-khmaty (Moscow: Kompozitor, 2000), p. 11.

↩ -

10

José Capablanca, “Chess,” cited in Edward Winter, Capablanca: A Compendium of Games, Notes, Articles, Correspondence, Illustrations and Other Rare Archival Materials on the Cuban Chess Genius José Raúl Capablanca, 1888–1942 (McFarland, 1989), p. 122.

↩ -

11

Nina Berberova, The Italics Are Mine, translated by Philippe Radley (London: Vintage, 1991), p. 352.

↩ -

12

S. S. Prokofiev: Materialy, dokmenty, vospominaniia, p. 453.

↩