Ian Buruma’s life would itself make a nice subject for a novel. His father was Dutch; his mother was British, from a family that emigrated from Germany in the nineteenth century; as an undergraduate in the Netherlands he focused on Chinese literature, then moved to Tokyo, where he turned himself into an expert on Japanese cinema. He went on to work in Hong Kong, London, Budapest, and Berlin. He has written about everything from yakuza tattoos to V.S. Naipaul to the ideological pedigree of Islamism.

So it does not come entirely as a surprise that his second foray into fiction1 should draw its energy from a protagonist whose life also embraces migration and masquerade, the command of several languages, and, not least, an enduring fascination with the seductions of the movie screen. Just to make things even more interesting, the fictional character at the center of The China Lover draws her energy from the life of a real person, a Japanese actress, singer, journalist, and politician who today, at the age of eighty-eight, goes by the name of Yoshiko Otaka (née Yoshiko Yamaguchi, the name most often used for her in the novel).2 As Buruma’s wonderfully evocative imagining of her life explains, Yamaguchi/Otaka has borne a bewildering array of other aliases over the years. What she’s called depends entirely on whom you ask and when.

And that precisely is the conceit that motivates this brisk, shimmering tale of a life lived in the elusive overlap of feckless charm and ravenous opportunism. The heroine of The China Lover rarely gets the chance to tell her own story in the book—for reasons that are entirely appropriate to her biography. She spends much of her career in the power of others, a foil for the desires and delusions of government officials and movie moguls.

The book has three narrators, all of them men. The second section belongs to Sid Vanoven, a gay American and aesthete who comes to Japan in the years after World War II. The third, set in the 1960s and 1970s, is presented by Sato Kenkichi, a porn-movie auteur and TV journalist turned terrorist. The first, the literal and figurative centerpiece of the book, is recounted by Sato Daisuke, a propagandist and spy for Manchukuo, the Imperial Japanese puppet state in Manchuria before and during the war.

The first section seems to me the novel’s real center of gravity not only because it’s the richest and in some ways most evocative of the three, but also because it’s here that we learn about Yamaguchi’s origins. Her family, Daisuke explains, moved to Manchuria as Japanese colonists; her father is a compulsive gambler and general ne’er-do-well. As she grows up, her talent as a singer and actress soon becomes apparent. But there is something else that makes her almost irresistible to the scheming apparatchiks of the Japanese occupation regime—something captured by Sato Daisuke in his characteristic gushing idiom:

It was her eyes that left the deepest impression. They were unusually large for an Oriental woman. She didn’t look typically Japanese, nor typically Chinese. There was something of the Silk Road in her, of the caravans and spice markets of Samarkand. No one would have guessed that she was just an ordinary Japanese girl born in Manchuria.

Yoshiko is a Japanese national, but she’s spent most of her life in China, and she speaks the language fluently. Having studied European classical music under a Russian emigrée singing teacher to boot, she’s as multicultural as they come. Paradoxically, it is just this combination of attributes—along with her good looks and natural star power—that makes her the perfect embodiment of the Japanese colonial project in China.

It’s a project that can really use the help. Early-twentieth-century Japan was both a latecomer and an outsider to the game of imperialism, the first non-Western nation to compete with the European countries that had already been in the business for centuries. In 1932, after decades of commercial and military expansion into the northeastern corner of China, the Japanese consolidated their control over the region by transforming it into a pseudo-state dubbed “Manchukuo.” Manchukuo became the proving ground of Pan-Asianism, an ideology that (in the form propagated by the Japanese) revolved around the notion that Tokyo’s version of colonialism was actually enlightened and progressive, one in which Asians were their own “masters” rather than the subjects of cynically racist Westerners. Japanese-occupied Manchuria, in this reading, was a modernizing laboratory of interethnic harmony among the “native peoples” of the region (the Han Chinese, the Koreans, the Mongols, the Manchus, and the Japanese).

The reality, of course, was quite different. Even as Japanese settlers flowed into the territory to claim homesteads on its plains, local Chinese stepped up a desperate guerrilla war against the occupation that would continue right up until the end in 1945. The Kwantung Army,3 the Manchurian fiefdom of the Japanese military, was renowned for its brutality. Among its other dubious achievements, Manchukuo was home to Unit 731, a biological warfare research unit that pursued its mission with a zealousness that has often been compared to Josef Mengele’s work in Auschwitz. Meanwhile a vast Japanese bureaucracy was busily organizing the exploitation of the region’s ample coal and oil resources, a crucial part of Japan’s efforts to fight World War II; slave laborers were put to work wherever the occupiers deemed it appropriate. In one particularly devilish bit of political theater, the Japanese installed Pu Yi, who had been stripped of his throne as the last Chinese emperor a few years earlier, as Manchukuo’s putative “head of state”—though the real decisions were of course made by his Tokyo-appointed “advisers.”4

Advertisement

Though we occasionally catch glimpses of this unhappy history through the scrim of Sato Daisuke’s telling, that is not at all his intent. As he tells us, he wholeheartedly approves of Japan’s “civilizing mission” in Manchuria—even if, perceptive observer that he is, he can’t help but reveal its darker side in unguarded moments. Here he is, for example, on Pu Yi’s coronation:

Frankly, the ceremony was not entirely devoid of comedy. And yet there was an unmistakable sense of grandeur about the occasion. People need spectacles to nurture their dreams, give them something to believe in, foster a sense of belonging. The Chinese and Manchu people, demoralized by more than a hundred years of anarchy and Western domination, needed it more than most. And—although people tend to forget this now—we Japanese gave it to them; we gave them something larger than themselves, a great and noble goal to live and die for.

Daisuke, you see, is not only a true believer in Japan’s neocolonial mission; he’s also a romantic, an ambitious poseur who has fled the provincial parochialism of his small-town home in Japan for the broad vistas of Manchuria. For someone like him, Manchukuo promises liberation and opportunity, a frontier that offers upward mobility and much-needed relief from the cramped conformity of society back in the home islands:

Arriving at the port of Dairen, at the southern tip of Manchuria, to me felt like arriving in the great wide world. Even Tokyo felt narrow and provincial in comparison. Cosmopolitanism was in the very air. Apart from coal dust and cooking oil, you could pick up the pungent melange of pickled Korean cabbages, steaming Russian pierogis, barbecued Manchurian mutton, Japanese miso soup, and fried Peking dumplings.

He’s actually not exaggerating much. For all its nastiness, 1930s Manchuria also became home to an extraordinary assemblage of colorful characters. White Russian fascists, sworn enemies of Stalin, coexisted uneasily with Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, while Japanese gangsters cultivated ties with Chinese warlords and opium dealers. Manchukuo, during its short life span, became a sort of Japanese version of the Raj, a place whose alluring exoticism and wide open spaces exerted a powerful pull on the national imagination.

If you were a soldier in the Kwantung Army, service in turbulent Manchuria offered near-limitless opportunities for career advancement. If you were an enterprising bureaucrat, you could pursue administrative experiments that would never get off the ground back in stuffy Tokyo—demonstrated most memorably by Nobusuke Kishi, the man who served as Manchukuo’s equivalent of Nazi industrial czar Albert Speer5 and who would go on to become an eminently pro-American prime minister in postwar Japan. (Kishi crops up at several points in the novel.) Countless farmers, entrepreneurs, and adventure-seekers were enticed to Manchukuo out of similar motives.

For Yoshiko Yamaguchi—and her patron Daisuke—it’s the movie business that offers the path of opportunity. Daisuke, whose duties include building up the nascent Manchukuo movie industry, discovers Yoshiko performing in a theater in Mukden (present-day Shenyang), and a partnership of far-reaching consequences is born. At the time of their meeting, Yoshiko and her family have been taken under the protection of a Chinese grandee, who has, along the way, officially adopted her, bestowing upon her the dual names of Pan Shuhua and Li Xianglan.

It’s under the Japanese version of the latter name, Ri Koran, that she will go on to stardom in a series of film roles featuring her as the flamboyant, tempestuous, and mysterious Chinese beauty—a tantalizing idealization at the very moment Japanese troops are doing their best to viciously suppress anything that might suggest a Chinese national identity. An extraordinary fad for things Chinese, soon known as “the China Boom,” seizes the homeland, and Daisuke is there, in 1940, when fans of Ri’s hit song, “China Nights,” go berserk in the Tokyo theater where she sings. Even as she becomes hugely popular, her handlers have their hands full concealing her real, Japanese nationality.

Advertisement

This talent for pretending to be something she’s not is one she shares with the man who’s telling her story. Daisuke’s fluent command of the language also allows him to submerge himself in the local culture. Like Yoshiko, he has his own Chinese alias and wears the best Chinese fashions. And yet, as demonstrated by their diverging fates, she has one big advantage over him. She’s a naïf, seemingly oblivious to the twists and turns of ideology. “Politics always confused her,” we are told at one point. This turns out, in its way, to be a source of strength. Unlike Daisuke and many other Manchukuo true believers, she is happy to shuck the old utopias as soon as she gets the chance. After the end of the war, when the Chinese authorities are preparing to execute her as a traitor, she saves her life by proving that she’s actually Japanese, a foreign national. (Only natives, you see, can commit treason.) Daisuke, by contrast, is paralyzed by the failure of Japan’s fairy-tale designs for a “New Asia,” and later commits suicide in postwar Tokyo.

We catch a glimpse of these diverging fates in the second section, when Sid Vanoven, the American narrator, is recounting Yoshiko’s efforts to re-brand herself as a Hollywood star in US-occupied Japan. When Daisuke turns up at one of her press events, she deftly gives him the brush-off; he’s part of a past she would rather not recall. (She will later tell one of her interlocutors that “Ri Koran is dead.”) Small wonder. Now rechristened “Shirley Yamaguchi,” she’s too busy cozying up to American occupation officials and film producers to be reminded of that nasty Manchukuo business.

Sid Vanoven’s own biography, as a closeted homosexual who has fled the stifling confines of Middle America for louche postwar Tokyo, perfectly qualifies him to shadow her metamorphosis.6 He’s enthralled by the texture of life in Japan yet never falls into the messianic naiveté of his compatriots who are trying to remake the country in their own image. Vanoven—yet another character in The China Lover who is addicted to the movie business—has come to Tokyo as a junior official in General Douglas MacArthur’s occupation government. He works, for a time, in the censorship department, which is charged with promoting “democratic values” through the medium of the reviving Japanese movie industry (sometimes with unintentionally comic results).

This is a mission, of course, that bears some structural resemblance to the one pursued by Yoshiko’s patrons in Manchukuo, and here, too, it’s one that enables the narrator to appreciate her protean gifts. Yet Vanoven, unlike Daisuke, is cynical enough to sense what’s really going on. He watches with bemusement as Yoshiko beguiles an emissary from Hollywood:

“You were exploited, weren’t you,” he said, “by the militarists.”

She sighed. “Yes, I was.”

“It must have been very hard for you.”

“Yes, yes, it was,” she whispered, as tears made little tracks down her white powdered cheeks.

Though her new career as an American film star never quite takes off, she does, at least, get a husband out of the experience: the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi, yet another character blessed, or crippled, by a surfeit of potential identities. When he comes to Japan to live with her, he tries to compensate for his own foreignness by aspiring to be more Japanese than the natives. Their marriage will founder as a result.

In this he is typical of many of the male characters in the novel. Yoshiko, making the most of their ambition and desire, always manages to slough off her old identity and move on when the situation demands it. The men, left behind, all too often end up as the captives of their own illusions. This is literally the case with the novel’s third narrator, Sato Kenkichi, who tells his story from a jail cell in Beirut. It’s a particularly tangled tale: he’s a frustrated student radical and cinema enthusiast who ends up working in “pink movies”—erotic cinema that, in 1960s and 1970s Japan, bizarrely commingles perversion and politics. The specialties of the genre include “Yankee base movies,” porn flicks that depict US soldiers having their beastly way with innocent Japanese girls. (Of one particularly popular director, Kenkichi recalls: “Everyone just adored the King of Rape.”)

Later he’s recruited by a Japanese TV network to help Yoshiko put on a current affairs program for housewives. The job takes the two of them to Vietnam at the height of America’s war there, as well as to the Middle East, where they come into contact with a small band of Japanese left-wing radicals who have thrown in their lot with Palestinian terrorists. Lured partly by an infatuation with one of the Japanese sympathizers, partly by his own inchoate revolutionary romanticism, Kenkichi ends up joining a terrorist cell that stages one of the most horrific attacks of the era, the Lod Airport massacre in May 1972, a random shooting that killed twenty-six people and left dozens of others wounded.7 At first he and his terrorist comrades are welcomed as heroes throughout the Arab world, but later, amid the shifting of political winds, he’s arrested and thrown in jail by the Lebanese.

Yoshiko, of course, continues her odyssey of reinvention, and while Kenkichi is in prison he receives affectionate letters describing her growing celebrity as a trendily progressive TV journalist. Muhamar Qaddafi, Kim Il Sung, Yasser Arafat—she can’t praise them enough for their great deeds. (Her verdict on Idi Amin: “I adored him.”) When she tells Kenkichi that she’s accepted an offer to join Japan’s staunchly conservative ruling party (an offer extended by its notoriously corrupt leader, Kakuei Tanaka, no less), she hardly misses a beat.

Yet none of this disillusions Kenkichi; indeed, just the opposite. Instead he succumbs to a mystical fascination with Yoshiko, whose past as the legendary Manchurian movie star Ri Koran only seems to heighten the enigma of her infinite adaptability. The sensual deprivation of life in prison intensifies what he calls “the movies in my head” to the point of manic obsession, and the book ends with his invocation of Yoshiko’s magical image:

In the isolation of my prison, I finally made peace with myself. For I, too, have a capacity for worship. I worship what religious people call the craven image. That is why Ri Koran will never die. Nor will Yamaguchi Yoshiko, or even Shirley Yamaguchi. For long after my Yamaguchi-san turns to dust, they will live on, wherever there is a film, a screen, and a projector of light.

Earlier in the novel we’ve heard Sidney musing that “immortality could only be achieved on the silver screen”—though it’s a funny kind of immortality, bound up in the ephemerality of the medium:

I remember Kurosawa once saying: “Castles in the sand, Sidney-san, that’s all we’re doing, building castles in the sand. One single wave is all it takes to make everything disappear forever.”

Yes, that’s the canonical director Akira Kurosawa; one of Yoshiko’s many distinctions in this novel is her role as the actress in the first on-screen kiss in Japanese cinema, an innovation urged by the Americans, with Kurosawa directing. In this novel of shape-shifters, the same people who worship the powerful mimesis of the movies are also intensely alive to their transience.

All three of the narrators, as well as Yoshiko herself, use the movies to escape the confines of blinkered provincialism. Sex is another way of jumping the bounds of identity. Sato Daisuke’s romantic obsession with China is mirrored in his greed for the bodies of Chinese women. Kenkichi’s migration from his home in the boondocks (where his mother works in the local movie theater) to Tokyo opens up a world of sexual temptation. Sid, of course, is an outsider, a foreigner whose sexual proclivities nonetheless give him something like privileged access to the insiders’ club that is Japanese society. But there are limits, of course. Every time he engages in furtive acts of love in men’s bathrooms around Tokyo, he is “hoping I could possess something of the Japanese; the act of love as a route to transfiguration.” Gradually, having acquired command of the language, he achieves that paradoxical status of the “crazy foreigner who truly did have some understanding of Japan,” a figure regarded with alternating admiration and suspicion by the people of his adopted country.

It is Sidney who most explicitly addresses the novel’s most densely embroidered theme—the clash between the human longing for enduring ideals and the irresistible human urge for change. Anyone who’s spent time in postwar Japan can probably understand where he is coming from:

People often ask me how the Japanese could have changed so suddenly from our most ferocious enemies, ready to fight us to the death, to the friendly, docile, peace-loving people we came across after the war was over. It was as if some magic switch had been pulled to transform a nation of Mr. Hydes into a nation of Dr. Jekylls.

Sid speculates that the answer to this conundrum might be one of a fundamentally practical nature: “Aware of what their own troops had done to others, the Japanese wanted to make sure we wouldn’t pay them back in kind.” For many Westerners, he notes, this merely suggests that the Japanese are a nation of “double-faced liars,” people somehow capable of switching at a moment’s notice from emperor- worshiping fanatics to “docile peace-lovers.” But he doesn’t quite agree. Instead he proposes a more modest theory:

Westerners, believing in one God, prize logic. We hate contradictions. To be authentic is to be consistent. But the Oriental mind doesn’t work that way; it can happily contain two opposite views at the same time. There are many gods in the Orient, and the Japanese mind is infinitely flexible. Morality is a question of proper behavior at the right time and place.

We aren’t supposed to take this quite at face value, of course—perhaps signaled by that anachronistic word “Oriental,” which, almost without noting it, we have now relegated to the same spiritual epoch as “negro.”8 But it’s a thought that resonates in this novel’s labyrinth of identities.

Buruma, of course, didn’t write this novel to give us a history lesson. Its pleasures derive from its cascading variations on the theme of reinvention, its multiple voices spiraling around the one real “essence” that human animals can claim—the capacity for self- transformation, the quest for new selves, the urge to live what can be imagined. There’s always a temptation to romanticize this impulse, but in fact it’s not so simple. Yoshiko’s single-minded malleability will, perhaps, leave the reader with a certain sense of bemused admiration, but there is a blitheness to her opportunism that unnerves. Toward the end of the book she denies acquaintance with Sidney just as offhandedly as she once disavowed her former patron Daisuke. She has an amazing capacity for believing the slogans that have been handed to her by the powers of the moment, always disarmingly claiming her innocence.

One might argue, in her defense, that she ends the book where she started it, arguing the cause of “peace” as the political value to be pursued above all. The problem with this, of course, is that “peace,” taken in isolation, ends up meaning whatever you want it to. Yoshiko is a peacenik in Manchukuo (where “peace” means defending the status quo of the Japanese occupation), in US-occupied Japan (where it involves promoting good relations between the defeated Japanese and their new tutors), and in the 1970s world of internationalist radical chic (where it translates into cozy approbation of any dictator who claims loyalty to the same vacuous principle). Yoshiko’s take on the Jews is particularly fascinating. One of her childhood friends back in Manchuria was one, and she knows their story well:

Yes, I’m Japanese, I know, but Japan was never my home. My home is in China. Once you lose your home, you’re a rootless wanderer. People call me a cosmopolitan. They say the world is my home. I’ve often said so myself. I like to think that it’s true. But in fact, in my heart, I’m homeless, like a Jew. Which makes the suffering of the Palestinians even more astonishing to me….

The Jews, who have suffered themselves, have become the new oppressors. But we Japanese, who were the oppressors once, must help the oppressed. This time, we must be on the right side.

That’s Yoshiko in fashionable anti-imperialist mode. But just a few pages later we see her, now a member of the conservative ruling party in Japan, explaining to Kenkichi in a letter why she’s decided to support the Japanese government’s pro-Israel policies—because “we are also a weak Asian nation, dedicated to peace but living in a dangerous world.” Which means that Japan has to seek shelter in its alliance with the US, a country in which “Jewish opinion” is highly influential. The transitions are almost effortless.

There are moments when the cleverness of the novel’s construction—an intricate lattice of mirrored obsessions—threatens to overwhelm the lived experience of its characters. The people who inhabit this world sometimes have a bit too much in common for their own good. Both Sid and Daisuke—characters of entirely different backgrounds and philosophy—use the same, oddly didactic phrase (“black Prussian-style uniforms”) when describing nineteenth-century images of Japanese soldiers. At one moment Sato Kenkichi, a character not otherwise greatly distinguished by self-knowledge, suddenly sounds more like a professor in the cultural studies department of an American university than a Japanese pornographer:

The sex itself, by the way, was also bound by certain unalterable conventions: most sex acts, including rape, torture, even murder (strangulation with a kimono sash was popular at the time), were permissible, but the sight of even a single pubic hair was strictly forbidden. Genitals, male or female, were absolutely banned from the screen.

On the other hand, as sheer black humor this is hard to beat, so perhaps we should just let it be. Quibbles aside, The China Lover is a marvelous, sarcastic romp through twentieth-century history, and Buruma is to be congratulated for bringing it off with such panache.

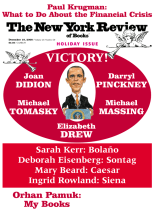

This Issue

December 18, 2008

-

1

His first novel was Playing the Game (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1991).

↩ -

2

Buruma specifically credits her autobiography, Ri Koran, Watashi no Hansei (Half My Life as Ri Koran), by Yoshiko Yamaguchi and Fujiwara Sakuya (Tokyo: Shincho Bunka, 1987).

↩ -

3

Buruma refers to it by its Japanese name, the Kanto Army.

↩ -

4

Movie buffs might recall the opulent retelling of this story in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor. Some time ago Buruma hosted a documentary on Chinese history called Beyond the Forbidden City, which is now part of the Criterion Collection DVD edition of Bertolucci’s film.

↩ -

5

The comparison between Kishi and Speer is drawn by Buruma in his book Inventing Japan, 1853–1964 (Modern Library, 2003).

↩ -

6

Here Buruma has happily plundered the biography of Donald Richie, the US-born film critic and Japanologist whose hugely entertaining memoirs, The Japan Journals: 1947–2004 (Stone Bridge, 2004), are also acknowledged by Buruma as a source.

↩ -

7

Kenkichi’s story is based, again, on a real-life model, Kozo Okamoto, the only one of the three Japanese attackers to survive. As elsewhere in the story, however, Buruma cheerfully discards historical facts and timelines when they don’t suit his fictional purposes.

↩ -

8

It is one of the novel’s neatest ironies that its most enthusiastic Orientalizer—endlessly blathering about presumed “Asian” essences—is Sato Daisuke, a Japanese.

↩