Etched into the pedestal of a statue of Daniel Webster that stands in Central Park not far from where I live are the most famous words from Webster’s second reply to Robert Hayne during their “great debate” of January 1830: “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” Abraham Lincoln loved that speech and greatly admired the man who delivered it. For Lincoln, as for most Republicans in 1860, to revere the Union was to love liberty and loving liberty meant hating slavery. A lifelong Whig, Lincoln always saw his support for economic development as part of a larger vision of national unity. But after 1854, when he reentered public life as an antislavery politician, just about everything Lincoln said about the Union was closely bound up with his moral opposition to slavery. Lurking behind nearly every major political or military decision Lincoln made as president was his conviction that the problem of the Union and the problem of slavery were one and the same. So it’s not quite right to say that Lincoln cared more about the Union than he did about slavery. His concern for the Union was inseparable from his hatred of slavery.

“For the sake of the Union,” Lincoln argued in his 1854 Peoria speech, the old Missouri Compromise restrictions on introducing slavery into the western territories “ought to be restored.” Opening those areas to slavery, he warned, would raise “a grave question for the lovers of the Union.” More than an anomaly in a nation founded on the principle of universal liberty, slavery was for him a threat to the Union’s existence. In 1858 Lincoln likened the nation to a house at war with itself, doomed to bitter strife and unable to sustain itself “half slave and half free.” He often asked audiences whether any issue had ever unsettled the Union the way slavery had done repeatedly since the nation’s founding. His antislavery politics were guided by a kind of Platonic ideal of a Union that—once cleansed of slavery’s stain—would more closely approximate the true vision of the founders. Restrict slavery’s expansion, reaffirm the nation’s antislavery principles, and “we shall not only have saved the Union,” Lincoln concluded in 1854, “but we shall have so saved it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving.”

Lincoln said these things better than most politicians but he was hardly the only politician saying them, and not everybody agreed. Northern Democrats thought there was something sinister, even treasonous, in all the talk of an irreconcilable conflict between slavery and freedom. The real threat to the Union, they believed, was not slavery but the relentless obsession with it—by zealous supporters in the South and fanatic opponents in the North. Most Northern Democrats would fight and die for the Union, but they would not wage a war whose primary goal was the abolition of slavery. Starting from a very different premise—that slavery had destroyed the Union—most Republicans quickly concluded that it would be impossible to restore the Union without attacking slavery. A war for the Union, then, meant very different things to the loyal men and women of the North.

There was a critical sliver of common ground, however. Even if they disagreed over the morality of slavery, Democrats and Republicans in the North could agree that slavery had caused the war, that single-minded devotion to it had inspired widespread disloyalty to the Union in the slave states. Democrats really did care more about the Union than they cared about slavery, but it might be possible to convince many of them that the destruction of slavery was necessary if the Union was to be restored. A large part of Lincoln’s presidency, and no small part of his greatness, resided in his ability to persuade a majority of loyal Americans of something he himself had long believed—that the struggle for the Union was also a struggle for universal liberty.

1.

Between November 6, 1860, the day Lincoln was elected president, and March 4, 1861, the day he was inaugurated, the United States of America fell apart. As soon as the voting results were clear, the South Carolina legislature called a secession convention to meet in December. As expected, when the delegates met they voted overwhelmingly to secede from the Union. By then several other secession conventions had been called and, by February, six more Deep South states had followed South Carolina’s lead. On February 4 representatives from the seceded states met in Montgomery, Alabama, where they drafted a new constitution and, five days later, elected Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as interim president of the Confederate States of America. All of this had happened by the time Lincoln left his home in Springfield, Illinois, on February 11, on his way to the inauguration in Washington, D.C. Whatever else it was, this was no ordinary interregnum.

Advertisement

Yet it is one of the strengths of Harold Holzer’s Lincoln President-Elect that it reminds us of how much of Lincoln’s time was occupied with the ordinary things any newly elected president has to do. Lincoln put up with countless office seekers, held numerous conferences with fellow Republicans, selected his cabinet, and drafted his inaugural address. It was mostly familiar business. Before the era of civil service, presidents-elect got to make hundreds of patronage appointments, but because this was the first time the Republican Party had ever taken power there was a wholesale turnover of federal appointees that made Lincoln’s job more onerous than usual. As Holzer shows, Lincoln followed well-established tradition by filling many key cabinet positions with the men he had defeated for his party’s nomination.

But there was no precedent for the breakup of the nation that made the interregnum of 1860–1861 different from any other. In the first weeks after his election Lincoln scoffed at disunionist rumblings. Southerners had been making such threats for years; if he just kept quiet it would all blow over. By December Lincoln realized that secession was a genuine threat. In public he maintained a “stately silence,” urging nothing more than obedience to the law. But in private Lincoln resisted any sectional compromise that violated the Republican Party’s rock-solid opposition to slavery’s expansion into the western territories. By January, Lincoln decided that compromise on any basis was capitulation to secessionist blackmail. At some point early in the New Year he probably reached the conclusion that war was likely.

In February, when he left Springfield for Washington, Lincoln broke his silence and revealed his policy in a series of speeches along the way. He summed it all up in his uncompromising inaugural address. He would neither “coerce” nor “invade” the South, but he would enforce the law, hold on to federal forts, and uphold his constitutional obligation to maintain the integrity of the Union. Secession was anarchy, Lincoln said, and as president he would not tolerate it. The next day the Richmond Dispatch took due note of Lincoln’s aggressive tone. “The inaugural address,” it declared, “inaugurates civil war.”

Holzer’s account of these events is lively and thoroughly researched, but it suffers from some of the occupational hazards of Lincoln scholarship. It’s too long, and it sometimes attributes to the sixteenth president powers and abilities beyond those of mortal men. Holzer calls Lincoln “the master puppeteer” who pulled the strings and made Republicans dance to his tune even from faraway Springfield, Illinois. In fact nothing Lincoln said or did in the months between his election in November 1860 and his inauguration in March 1861 was out of step with the Republican Party line. Democrats and border state Southerners demanded that Lincoln say something, anything, to ease the sectional tension. Don’t do it, Republicans countered. They bombarded him with letters, editorials, and personal visits telling him to keep quiet and give no hints of accommodation. Until his inauguration, one Republican wrote, Lincoln should “not open his mouth, save only to eat.” All but a few Republicans resisted any compromise that would allow slavery’s expansion into the territories, and by January most of them resisted any compromise whatever. Anyone who wavers, Benjamin Wade explained, “is shot down in an instant by his comrades.” The Republican caucus was disciplining itself.

The screws of party discipline were fastened tight by the intense hostility to compromise welling up from the Republican base. Local Republican editors published exhortations and individual voters wrote impassioned letters to their congressmen demanding unbending allegiance to the party’s antislavery platform. “For God sake,” one anxious voter wrote to Republican Senator John Sherman of Ohio, “don’t Compromise.” As president-elect, Lincoln felt this pressure more than most Republicans. He received at least as many letters as he sent out counseling silence and resistance to compromise. It required no nerves of steel for him to toe the party line.

It was also easier for Lincoln to hold his tongue in Springfield than it was for the Republicans who convened in Washington when Congress came back into session in December. Confronted each day by the belligerent speeches of Southern congressmen, and forced to take positions on various proposals for sectional compromise, Republican politicians began to break their silence and by March most of them were on record denouncing secession and opposing any compromise of the party’s antislavery principles. When Lincoln himself began to speak out, beginning in mid-February, he said the same things most Republicans were saying: the Union was perpetual, secession was illegal, and the laws would be enforced.

If any group was responsible for holding the line against compromise it was the party radicals. They were the “stiffbacks” of the Republican organization. For the sake of building a winning political coalition they had accepted “free soil” (i.e., opposition to extending slavery rather than abolition) as the party’s ideological bottom line, though their own antislavery principles went much deeper. Having adhered to that minimal position they would compromise no further—especially not now, at the very moment of the Republican Party’s first great triumph. When a tumbling stock market prompted jittery merchants in New York and Boston to call for sectional reconciliation, it was the radicals who strongly objected. They are asking us, Charles Sumner complained, ” to surrender our principles.” Ohio radicals warned that they would bolt from the party if Republicans backed away from their own antislavery platform. “We will repudiate it with a full heart, and counsel all our friends to do the same.” Now was the time to stand firm, Joshua Giddings insisted. “We have degraded ourselves enough.”

Advertisement

Lincoln agreed. The consummate pragmatist steadfastly rejected any sectional compromise that conceded a constitutional right to own slaves in the territories. “Entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery,” he warned in a private letter in mid-December. “Have none of it. The tug has to come & better now than later.”

In rejecting compromise Republicans knowingly accepted the possibility of war. But war would require the enthusiasm of many Northerners who had voted against the Republicans, and Lincoln used his trip to Washington to build that support. His February speeches rang with a new militancy. Indeed they stand out in the Lincoln corpus for their bellicose and emotional appeal to nationalism. Lincoln riled up crowds by flattering them for their love of country and then inviting them to shout in uproarious approval. He asked leading questions. You will support me, won’t you? he would say. Won’t you? He protested the sincerity of his hopes for peace, “but it may be necessary,” he warned legislators in Trenton, “to put the foot down firmly.” He invoked the sanctity of the Union to rally support for an impending war even among those who did not really care about slavery.

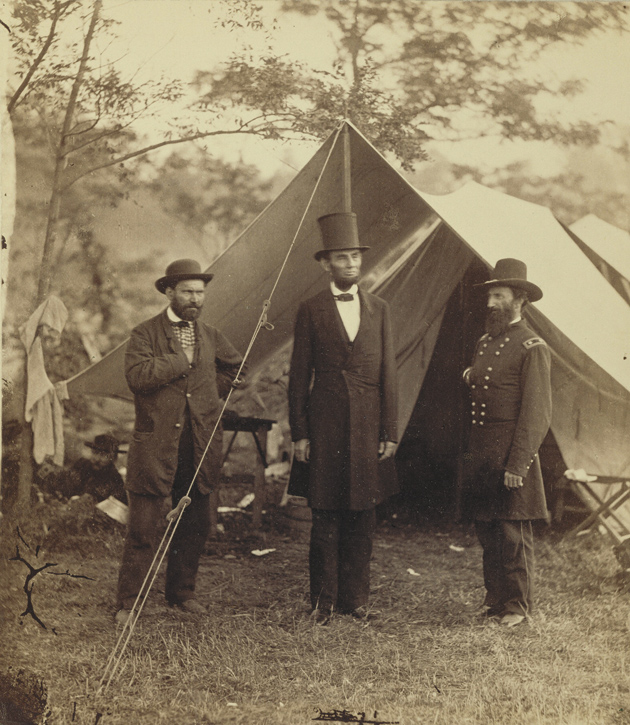

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Abraham Lincoln with intelligence chief Allan Pinkerton (left) and Major General John A. McClernand (right) in early October 1862, during a visit to the Antietam battlefield; detail of a photograph by Alexander Gardner. An albumen silver print of the full photograph is on view in the exhibition ‘In Focus: The Portrait,’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, through June 14, 2009.

2.

But a war fought primarily to save the Union could not avoid the problem of slavery. For Lincoln it came down to this: he could not win without the support of the War Democrats and the loyal border states (the slave states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri), but neither could he win the war on their terms—by leaving slavery alone. How could a war for the Union become a war for emancipation without losing their support? It would require, among other things, a skillful politician and an uncommonly effective communicator. It would also require, as Craig Symonds and James McPherson show, a commander in chief who understood that military and political strategies for winning the war could never be separated.

McPherson notes that Lincoln’s problems with his generals are famous, and Symonds now adds the six Union admirals to the familiar story. This could be told as a simple tale of clashing personalities—of George McClellan’s arrogance, David Dixon Porter’s ego, John C. Frémont’s incompetence, and Lincoln’s frustration. But as Symonds points out, much of the problem was structural. In 1861 there was neither a Pentagon nor a Joint Chiefs of Staff—no command structure capable of coordinating the movements of different branches of the service, no bureaucracy that could ensure the simultaneous movement of different armies in different theaters of war. Only the president, as commander in chief of the army and the navy, could fill that role. But because Lincoln had no military training and almost no military experience, he had to learn on the job, and he made mistakes.

Lincoln put in long hours of study mastering the theory of war and the principles of combat. In truth they weren’t all that complicated. First, wars are won by defeating armies, not capturing territory. Second, to overcome the South’s strategically defensive position, the North had to take advantage of its superior numbers by launching simultaneous attacks that would prevent the enemy from consolidating its forces. But Lincoln was frustrated by generals who, though often trained in those elementary precepts at West Point, nonetheless failed to act on them.

Lincoln’s first general in chief, Winfield Scott, imagined that a naval blockade would be enough to strangle the Confederacy into surrender. But the South could always feed itself and as long as its armies held the field Confederate independence was feasible. Yet Lincoln had a difficult time getting Union generals to understand that merely capturing Richmond, or kicking Confederates out of Maryland or Pennsylvania, was no replacement for destroying Robert E. Lee’s army. Nor did Lincoln have much better luck getting different generals, or generals and admirals, to coordinate their movements by launching simultaneous attacks.

Sometimes the problem was sheer military incompetence. Sometimes it was the lack of what military historians call “moral courage”—the willingness of a commander to send his men to their deaths in combat. But more than a few of the problems were political. The West Pointers were bad enough, but in the earliest years of the war Lincoln often felt compelled to appoint “political generals”—militarily inept, many of them, but nevertheless appealing to Massachusetts Republicans, Illinois Democrats, or German-Americans. Sometimes national political strategy dictated undesirable military strategy—as in Lincoln’s decision to press ahead with the disastrous Red River campaign in Louisiana instead of following Ulysses S. Grant’s preference for closing off Mobile Bay. “It was impossible,” Craig Symonds writes toward the end of Lincoln and His Admirals, “to keep politics and strategy completely separate.”

Slavery posed the largest political problem of the war, however. Within weeks of Fort Sumter it became clear that the Confederacy could not secure its independence without the assistance of slave labor and that the North could not restore the Union without depriving the Confederates of that labor. Symonds’s discussion of slavery and the naval war is both original and important. Because of the navy’s early success in capturing some of the most densely populated plantation districts of the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts, it was a pioneer in the establishment of “contraband” camps for escaped slaves behind Union lines. Unlike the US Army, the navy had never excluded black sailors from its ships and as the number of contraband slaves swelled the navy began absorbing more black servicemen, months before black soldiers were able to join the Union army. Yet although the navy “had played its part,” Symonds concludes, “it had been mainly an army war.”

The “army war” is the focus of McPherson’s new book and, like Symonds’s, it reflects the unusually high standards of Civil War military history. But McPherson also brings special strengths to the subject. He began his career with two sympathetic books on abolitionism and a pathbreaking study of The Negro’s Civil War. That broad background enriched his two one-volume histories of the Civil War. Over the years McPherson has become a great admirer of Abraham Lincoln, and his admiration reflects the trajectory of his scholarship. As a young historian and a student of the abolitionists, “my own attitudes” toward Lincoln “reflected their continuing criticisms of him,” McPherson has recently explained.

Only after years of studying the powerful crosscurrents of political and military pressures on Lincoln did I come to appreciate the skill with which he steered between the numerous shoals of conservatism and radicalism, free states and slave states, abolitionists, Republicans, Democrats, and border-state Unionists to maintain a steady course that brought the nation to victory—and the abolition of slavery—in the end.*

Lincoln’s successful navigation of these crosscurrents is the theme of Tried by War, a study of Lincoln as a commander in chief. But the book is also a distillation of McPherson’s wide-ranging scholarship and a demonstration of how effectively, and unpretentiously, he brings together his unparalleled command of the social, political, and military history of the Civil War.

Lincoln’s greatness as commander in chief derived from much more than his increasingly sharp instincts as a military strategist. For one thing, as good as they were, Lincoln’s instincts were never infallible. His obsession with the naval capture of Charleston, for example, nearly destroyed two good admirals. But Lincoln’s grasp of politics, and with it the interplay of military and political strategy, was unsurpassed. Lincoln quickly saw the “military necessity” of emancipation and, from the earliest weeks of the war, he helped set in motion and guide the long process of slavery’s eventual abolition. He knew that a crucial part of this process involved preparing the political ground for popular acceptance of emancipation as a war aim. But he also understood that no matter how much political skill and verbal dexterity he could muster, popular support for the war depended on the ability of his generals to win battles.

3.

Many Northern minds would have to be changed before a war caused by slavery could become a war to abolish slavery. Radicals, whose stock rose dramatically once the war started, argued from the beginning that emancipation was a military necessity essential to the restoration of the Union. Their efforts became organized through “union leagues” that worked to build support for the war and emancipation—for Union and liberty. Lincoln relied on this radical campaign. Years later the abolitionist Moncure Conway recalled a meeting with the President in early 1862. “We shall need all the anti-slavery feeling in the country, and more,” Conway remembered Lincoln saying. “You can go home and try to bring the people to your views; and you may say anything you like about me, if that will help. Don’t spare me!” But it wasn’t only radicals who strongly opposed slavery.

Congregations in the North published memorials declaring that God would not end the bloodshed until the sin of slavery was erased from the national conscience. Lincoln joined this propaganda effort. He began writing letters, not for private consideration but for public consumption—letters designed to be published, to be read aloud, to persuade, to mold public opinion, because in a democracy, Lincoln believed, public opinion is everything. These letters are minor masterpieces, without parallel in the annals of the American presidency.

The first of them, cited by McPherson, was in reply to an editorial by the influential publisher Horace Greeley imploring Lincoln to issue an emancipation proclamation. In his response Lincoln declared that although it always had been his personal wish to see slavery abolished, his primary charge as president and commander in chief was to restore the Union. He spelled out what appeared to be three possible ways to achieve his goal: by freeing all the slaves, by freeing none of the slaves, or by freeing some of the slaves. Presumably Lincoln would choose whichever option would most rapidly restore the Union.

But in fact the three options were bogus. Lincoln had already declared that the slaves who had escaped to Union lines were “liberated” and could never be returned to slavery, and he had already signed a law abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C. It was no longer possible to restore the Union without freeing any slaves. Lincoln had also said on numerous occasions that the federal government had no power to force emancipation on the four border slave states that had remained loyal to the Union. Constitutionally, then, he could not free all the slaves. The only possibility left was that he would restore the Union by proclaiming the emancipation of some but not all of the slaves. And although Greeley did not know it at the time, Lincoln had already decided to do just that. So whatever else it was, the Greeley letter was anything but a straightforward recitation of Lincoln’s three options.

What, then, was Lincoln up to? It’s impossible to be sure, but the letter to Greeley has all the earmarks of a skillful public relations ploy. Lincoln knew that the proclamation he was about to issue would provoke hostility among those Northerners who would willingly fight to restore the Union but who would object to a war to free the slaves. By making it appear as though he had options to choose from regarding emancipation, and that he would choose the option most likely to restore the Union, Lincoln tried to nudge Northern public opinion along the path he had already decided to take.

Where the Greeley letter of August 1862 was coy about abolition, Lincoln’s letter of August 1863 to the Illinois politician James Conkling was a remarkably blunt defense of what was by then the explicit emancipation policy of the federal government. Thousands of freed slaves were already putting that policy into effect by enlisting in the Union army. Lincoln directly addressed those who objected, sometimes violently, to the transformation of a war to restore the Union into a war to emancipate the slaves. “You say you will not fight to free negroes,” Lincoln wrote to his critics. “Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union.”

It was the same debate he had engaged nearly a decade earlier, between those who wanted to keep slavery and the Union separate and those who thought the issues were inseparable. At Peoria, in 1854, Lincoln had imagined a Union without slavery and therefore “worthy of the saving.” The same sentiments reappeared in the Conkling letter a decade later. He looked forward to a peace that would be “worth the keeping in all future time.” When that time comes, Lincoln said,

there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.

It was a familiar theme, and it is no surprise that Lincoln returned to it in his last and greatest speeches. But by then the tone was different. Gone was the bellicose strain that had seeped briefly into his language while he was president-elect. The war had changed Lincoln, chastened him. Speaking at a mass grave in Gettysburg where only months before 50,000 Americans had been killed or wounded in a ferocious three-day battle, Lincoln invoked a nationalism that was hopeful rather than belligerent. With emancipation—“a new birth of freedom”—now one of the war’s aims, Lincoln believed that the Union had rededicated itself to the nation’s founding proposition that all men are created equal. The war was a test, he said, of whether the nation the founders had made, “or any nation, so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure.” Lincoln thereby folded universal freedom into the defense of democratic republicanism. Thousands of men had died at Gettysburg, Lincoln said, to ensure that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Darker and less exalted was the unionism of the astonishing Second Inaugural Address. There Lincoln not only rejected the tub-thumping patriotism of the secession winter but also avoided any hint of national triumphalism. We “all knew,” he said, that slavery was, “somehow, the cause of the war.” But no one could have imagined the staggering price we would have to pay to rid the nation of the thing that had brought the war on to begin with. The suffering has been unspeakable, Lincoln said:

Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

The war was about to end. In a few days Lee would surrender his army at Appomattox. Lincoln had every reason to revel in his triumph, but hubris would have been out of character with the man and with the tone he set on that occasion. Instead of screaming eagles, the unionism Lincoln now invoked was one of shared national responsibility for the “offence” of slavery. In 1801, after the bitter partisanship of the preceding presidential election, Thomas Jefferson appealed for national unity by declaring famously: “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” But the words of national unity that echoed from the Capitol steps on that late winter day in March 1865 registered Lincoln’s more sobering sentiment: we are all guilty.

This Issue

April 9, 2009

-

*

Abraham Lincoln (Oxford University Press, 2009), p. x.

↩