In response to:

The Russians Are Coming? from the February 12, 2009 issue

To the Editors:

Christian Caryl’s otherwise interesting review of Edward Lucas’s The New Cold War [NYR, February 12] requires two revisions. According to Caryl, unlike only a few months ago Lucas’s book now seems “more like prescience”; and, on a related matter, “freedom of the press” in Russia was “one of the few undeniably positive achievements of the Yeltsin years.”

I don’t know if there is pre-prescience, but in an article in The Nation, July 10, 2006, I argued that “The New American Cold War,” as I titled the essay, has been underway since the 1990s. Apart from the more than two years of “prescience,” the essential difference between my argument and Lucas’s is that while he blames only Moscow for this outcome, a view shared by Caryl and almost everyone else who comments on the subject in the United States, I hold Washington primarily responsible. As for freedom of the press, most serious Western scholars, as well as Russian journalists who remember the late 1980s, agree that it was an achievement of the Gorbachev years, not Yeltsin.

Both of these questions are central to an understanding of two fateful developments since the end of the Soviet Union—the missed opportunity for a real US–Russian partnership and for democracy in Russia. Both are treated at length in my forthcoming book, Soviet Fates and Lost Alternatives: From Stalinism to the New Cold War, which will be published by Columbia University Press in July.

Stephen F. Cohen

Professor, Department of Russian Studies

New York University

New York City

To the Editors:

As a reporter previously based in Western Europe and in Moscow for fifteen years, I take issue with one assertion in Christian Caryl’s otherwise excellent article. It is incorrect to state that “NATO enlargment was driven less by a grasping, hegemonic United States than by the desire of Washington’s European allies to stabilize the belt of newborn democracies to the east.”

In fact, it was the new democracies themselves that led the drive for NATO membership, with support from Washington. Western European nations were by and large circumspect, and generally preferred the European Union as a venue for the stabilization of the new democracies. The EU has proven, by any measure, a far more effective organization for anchoring nascent market-based democracies than membership in a military alliance.

Nick Spicer

Correspondent

Al Jazeera English

Washington, D.C.

Christian Caryl replies:

In response to Stephen Cohen, I don’t think anyone seriously disputes that Mikhail Gorbachev was responsible for opening up the Soviet press. It was Boris Yeltsin’s equally important achievement to protect that freedom at a time when it would have been all too easy for him to crack down on his myriad critics.

Professor Cohen claims that I “blame” Moscow for the new cold war—a shortcoming I share with “almost everyone else who comments on the subject in the United States.” He doesn’t seem to have understood my article, in which I reject the premise that a new cold war is underway. As for his broader argument, Russia’s relations with the United States (and Europe, which Professor Cohen—in this respect, perhaps more American than he is willing to admit—blithely overlooks) would be in much better shape today if Vladimir Putin had opted to maintain democratic institutions, the rule of law, and a critical attitude toward the less attractive aspects of the Soviet past.

As for Nick Spicer, I appreciate his nuanced caveat regarding NATO expansion. I do realize that some Western European governments preferred the European Union to NATO as an instrument for integrating the ex-Communist countries of the East. My argument would be that even the skeptics were ultimately forced to acknowledge that, given the EU’s lack of a credible security and defense policy, NATO enlargement proved the only way of adding that missing ingredient to the region’s potentially volatile security concerns.

Mr. Spicer could well be right that the European Union is a “far more effective organization for anchoring nascent market-based democracies than membership in a military alliance.” I’m just not sure how he knows this, when we consider that most European Union countries have also been members of NATO from the beginning. (Indeed NATO actually predates the EU, so it seems odd that it would be so summarily dismissed as a force for European stability.) If the North Atlantic alliance has been so superfluous to the whole enterprise, it is rather hard to understand why France (of all countries) has now decided to rejoin NATO’s integrated military command.

This is not to belittle the EU’s importance. It’s merely to restate the fact that military alliances still matter (even if we might prefer to think that they don’t).

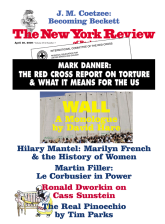

This Issue

April 30, 2009