During the years between the War of 1812 and the Mexican War of 1846, the United States underwent a great transformation. In 1815, at the close of the second war with Britain, the US was what we would call a “developing” country. Most people worked in agriculture, often on semisubsistence family farms, eating food they grew, their lives governed by the weather and the hours of daylight. It was the slowness and uncertainty of transportation and communications that kept their lives so primitive. Only people who lived near navigable water could readily market crops; others relied heavily on barter with their neighbors and the local storekeeper. Only luxury goods could bear the cost of long-distance transportation on land, and information from the wider world was among the most precious of luxuries.

Thirty-three years later, in 1848, at the end of the war with Mexico, much had changed. The United States had become a transcontinental major power. Its expanded empire stretched from sea to sea, integrated by revolutionary innovations in transportation and communications. These included the railroad, the telegraph, the steamboat, the Erie Canal, the steam-operated printing press, and innovations in papermaking. The mechanization of agriculture had begun, with Cyrus McCormick’s invention of the reaper in 1831 and John Deere’s steel plow in 1837. Techniques of mass production, even more important than mechanical inventions, were starting to transform manufacturing’s age-old artisan traditions.

These innovations not only raised the standard of living but also fostered the growth of democracy. Improvements in communications rescued people from the tyranny of isolation. Cheaper paper, more efficient printing, and faster transportation encouraged the proliferation of newspapers and magazines. These could be distributed through the mails thanks to federal policies that multiplied small-town post offices and subsidized printed matter with low postage rates. The press in turn facilitated the development of nationwide mass political parties. Many newspapers were put out by political parties (or factions within parties) and existed more to voice a point of view than for commercial reasons. American democracy expanded as rival candidates exploited the newspapers and magazines to appeal to the nationwide public. Andrew Jackson filled his “kitchen cabinet” of informal advisers with newspapermen. By 1840, as many as four out of five qualified voters were going to the polls—a far higher level of participation than has been achieved by the expanded electorate of recent decades. Mass democracy had replaced the patrician republic created by the Founders.

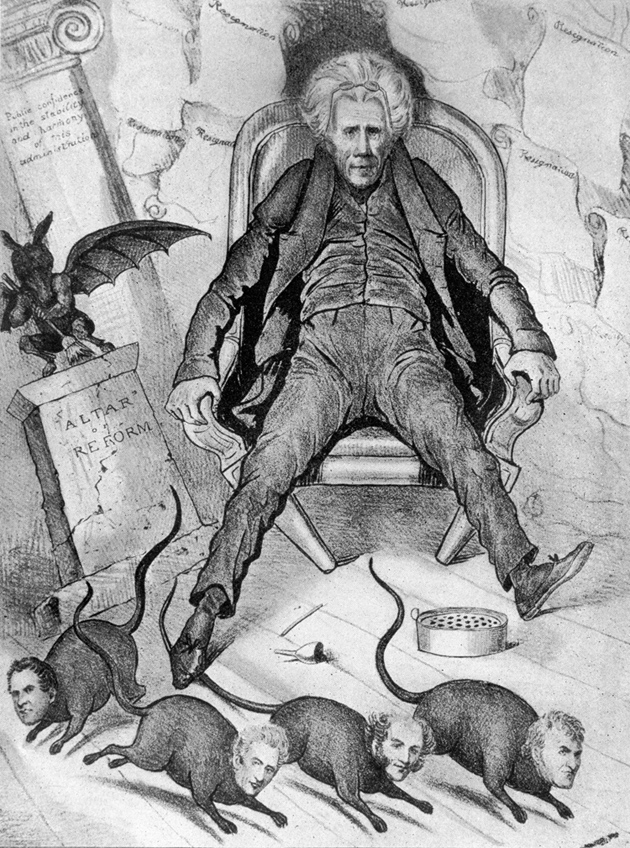

Since this “middle period” in American history is so interesting and important, why does it get so little attention compared with the Revolutionary era of the Founders and the time of the Civil War? Even academic historians have had little to say about it in recent years, if one may judge from the number of papers presented at meetings of the Organization of American Historians. The answer seems to have something to do with the identification of this period as “the age of Jackson” or “the Jacksonian era.”

Andrew Jackson has long been at the center of attention for the years from the War of 1812 to the war with Mexico. Rising to a position of political dominance in a peaceful revolution, he has seemed to personify the common man as an American hero. Over the years the identity of this “common man” has shifted. For the Progressive historians Frederick Jackson Turner and Vernon Louis Parrington in the early 1900s, the common nineteenth-century American was a frontier farmer. For the New Deal Democrat Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., he was an urban workingman. Still, Jackson could be portrayed by all three as the leader of a democratic movement.

During the past half-century the records of many national heroes have come under challenge, and none more so than Andrew Jackson’s. Historians noticed that Jackson, the symbol of American democracy, was an ardent white supremacist. Upon assuming the presidency in 1829, Old Hickory’s highest priority was “Indian Removal”: the expulsion of the Native Americans who lived east of the Mississippi to designated areas west of the river. Against strong opposition, Jackson pushed his removal measure through Congress by narrow margins and then enforced it ruthlessly. Turner, Parrington, and Schlesinger all ignored Indian Removal when writing about Jackson’s presidency; more recent historians could not do so.

Jackson was not only a slaveholder himself but a strong defender of slavery against its contemporary critics. In 1835 abolitionists began to mail their literature to prominent Southern whites who they hoped might be open to persuasion. Jackson interpreted their action as inciting the slaves to rebellion; he expressed his loathing for the abolitionists vehemently, both in public and in private. With the President’s full support, Postmaster General Amos Kendall encouraged local postmasters to censor the mails. When Congress responded with a statute mandating that mail be delivered to its addressee, Jackson’s administration ignored it.

Advertisement

Jackson’s embrace of class conflict has endeared him to some liberal historians, notably Schlesinger. When vetoing the bill extending the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, Old Hickory wrote this memorable denunciation:

The rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions…. But when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers—who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.

It should be evident that Jackson’s notion of class did not pit the propertyless against capitalism, but (as the historian Richard Hofstadter long ago pointed out) rallied believers in bourgeois values to denounce government favoritism to a privileged few. Beginning with Edward Pessen’s study Jacksonian America in 1969, the claim of Jackson’s political movement to egalitarianism has been under serious challenge.

With regard to gender, Andrew Jackson proved a staunch defender of patriarchy. “I did not come here [to Washington] to make a Cabinet for the Ladies of this place,” he declared in reaction to a group of Democratic women who shunned the wife of his secretary of war, John Eaton, because of allegations that she was sexually promiscuous and that her affair with Eaton before their marriage had driven her first husband to suicide. As the scandal grew more intense, Jackson told his cabinet members that he expected them to keep their wives in line. Rather than admit the existence of a social sphere in which women exercised autonomy, Jackson then replaced his entire cabinet.

As Jackson’s standing in the American democratic pantheon has been shaken, public interest in the middle period of US history as a whole has diminished. Without Old Hickory as a unifying focus, no alternative intepretation of the era has yet captured the popular imagination. To be sure, efforts have been made to reconstitute the “Jacksonian” character of the time. In 1991 Charles Sellers described his vision of an evil “Market Revolution” forced upon unwilling, noncommercial farm families—a vision that resembled that of Vernon Parrington to a surprising extent. In this morality play, Jackson led the vain but heroic resistance to commercial capitalism.

However, economic historians have not confirmed Sellers’s celebration of subsistence farming, and have pointed out that Americans were dealing in a global market as early as colonial times. As recently as 2005, Sean Wilentz restated Schlesinger’s interpretation of Jackson as the cutting edge of “the rise of American democracy.” But Wilentz has moved away from the history of the nineteenth century, as did Schlesinger himself, and into the politics of the present. For the most part, both historians and the general public have found it harder and harder to regard Jackson as an authentic democratic hero.

Against this historiographical background, we now have Jon Meacham’s American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. One can only marvel that the editor of Newsweek finds so much time and energy for historical research and writing. Like Meacham’s other books, his new one is well written and reflects study of original manuscript sources. It contains more personal detail and charming anecdotes about White House life in the Jackson years than any other book since Marquis James’s Andrew Jackson: Portrait of a President (1937). Meacham places himself in the mainstream of present-day American liberalism. Accordingly, he makes no effort to defend Indian Removal, justly concluding, “There is nothing redemptive about Jackson’s Indian policy.”

Meacham is loath to admit, however, that there was a difference between the Indian policy pursued by Andrew Jackson and that of his predecessor and political opponent, John Quincy Adams. Jackson zealously pursued Indian Removal as a major goal of his administration. On the other hand, Adams tried as president to respect the Indians’ treaty rights as best he could even while recognizing that the behavior of their white neighbors made this very difficult. After Jackson’s inauguration, Adams saw that the Indians were likely to lose their land, but he wanted to expose the “perfidy and tyranny of which the Indians are to be made the victims.” Jackson rejoiced in Indian Removal as a triumph for himself, his party, and US national interests. His instructions to the army officers who carried it out always emphasized haste and sometimes economy, but never the need for humanity, honesty, or careful planning. Adams recalled Indian Removal as “a perpetual harrow upon my feelings.”

Advertisement

Meacham’s evaluations of Jackson’s other policies in office vary. Arthur Schlesinger had glorified Jackson’s “war” on the national bank as an attack on big business that prefigured Teddy Roosevelt’s assault on “malefactors of great wealth.” Meacham adopts a more detached and judicious perspective. “On balance,” he writes,

it seems most reasonable to say that the nation’s interests would have been best served had the Bank been reformed rather than altogether crushed, but balance was not the order of the day once Jackson decided—as he had done early on—that the Bank was a competing power center beyond his control.

Meacham praises Jackson’s handling of the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, as everyone does today, and as even the opposition party did at the time. South Carolina “nullified” two federal tariff acts when a special convention declared them null and void within that state. Jackson’s credible threat of military action to enforce federal law combined with Henry Clay’s famous aptitude for compromise resolved the crisis with the promise that the tariff would be gradually lowered. On the other hand, Meacham grants that Jackson’s Specie Circular of 1836—which required payment for government land in gold and silver and not paper currency—nudged the country into a sharp recession that turned into a prolonged depression. In short, Meacham’s verdicts on Jackson’s presidential policies are mixed and restrained.

Yet at the end, Meacham glorifies Jackson as a lion in the White House. He rejoices that Jackson was a strong president, and that later strong presidents—the two Roosevelts and Truman—looked back on his example with approval. Well, yes, Jackson was a strong president, but his strength was charismatic and personal rather than institutional. He did not strengthen the presidency as such; if anything, his abuses of power (such as removing the government’s deposits from the national bank, in defiance of statutory law) made people fearful of the executive branch.

After Jackson, there commenced a series of weak presidencies. Of his next eight successors, only one, James Knox Polk, could be considered strong, and even he served only one term. The next strong president, Lincoln, had belonged all his adult life to the party opposed to the Jacksonian Democrats (that is, first the Whigs and then the Republicans). Lincoln was certainly no disciple of Jackson’s, although he cited Jackson’s resistance to nullification once in a while for tactical reasons. Lincoln pursued the policies of John Quincy Adams, who shared his loathing for slavery, supported much the same program of federal aid to transportation, education, and industrialization that Lincoln enacted, and foresaw not only civil war and emancipation, but even the mechanism by which emancipation could occur—the presidential war powers.

A further irony cries out for notice. Why should a liberal like Meacham celebrate a strong presidency per se? Maybe Barack Obama will be accounted a strong president. But as of now we haven’t had a strong liberal Democratic president for over forty years. We have had some strong Republican presidents in that time: Reagan, Nixon until overcome by Watergate, the younger Bush until overcome by Iraq. Hasn’t Meecham read Schlesinger’s Imperial Presidency , which testified to the author’s disillusionment with a strong executive?

Robert Remini, official historian of the US House of Representatives, has devoted most of his long and prolific career to lives of Andrew Jackson and his famous contemporaries Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Martin Van Buren, John Quincy Adams, and Joseph Smith. His latest book is a military biography of Jackson that appears in a series called Great Generals, edited by former NATO commander Wesley Clark. Lucid and straightforward, it will no doubt prove useful to cadets and military history buffs of all ages, and it will remind students of political history that Jackson always remained primarily a military man. Remini is a scrupulous and honest researcher who never bends his findings to his wishes. Although he much admires Jackson, Remini admits that his hero obeyed orders only when he agreed with them, committed wholesale violations of civil liberties, and owed his victories as much to luck as military skill. By my count, this is Remini’s fourteenth book on Jackson. If there is anything very new in this one, he doesn’t point it out.

David Reynolds’s ambitious book, Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson , is the work of a literary historian who has turned to the social context of literature (what literary scholars call “cultural studies”) and then to history itself. Clearly he wants to remedy the lack of public interest in the middle period, a worthy goal, and to call attention to the rich diversity of America in that era. Accordingly, Reynolds writes about politics and popular culture, literature, drama, and art, and he is particularly perceptive in his comments on painting. He describes the religious movements of the day, emphasizing their multitudinous variety. Bizarre fringe groups especially engage his attention. He gathers together in one chapter “reforms, panaceas, inventions, [and] fads,” including a good account of the temperance movement and some elementary history of science. Reynolds explains his approach this way:

Most overviews of the period slight its bumptious, nonconformist, roistering elements, its oddities and cultural innovations—its Barnum freaks, crime-filled scandal sheets, erotic pulp novels, frontier screamers, mesmeric healers, half-mile-long paintings; its street-fighting newspaper editors, earth-rattling actors, incarcerated anarchists; its free-love communes, time-traveling clairvoyants, polygamous prophets, and table-lifting spirit-rappers—all of which created social ferment and provided fodder for energetic American literary and artistic masterpieces.

Unfortunately, Reynolds never develops an interpretation of his period beyond his fascination with variety and oddity. He does not recognize the spiritual hunger that the various religions addressed, the moral earnestness of the varied reformers, or the very real differences of policy between the rival political parties. He never explains why people had such intense faith in progress, or the relationship between science and religion at the time. He presents considerable material on sex, including masturbation, prostitution, and abortion, but seems chiefly interested in the sensational aspects of the material, like the coverage in the penny press of the murder of the prostitute Helen Jewett. Reynolds makes superficiality a virtue; America, he keeps insisting, was superficial, sensational, and tawdry.

While trying to break new ground, Reynolds retains the conventional sense that Andrew Jackson embodied the democracy of his period; to believe in democracy was to support Jackson politically. Accordingly, Reynolds minimizes Jackson’s white supremacist policies. He represents Indian Removal as simply reflecting a consensus among whites, ignoring the powerful opposition to Jackson’s expulsion program. He characterizes Jackson’s censorship of antislavery mailings as a moderate measure designed to “prevent conflict over slavery”; it would be more accurate to describe it as designed to protect slavery from criticism.

Only three years before the publication of Waking Giant , Reynolds published John Brown, Abolitionist , portraying the antislavery fanatic as a hero and denying that he was a terrorist, despite his murders of Southern settlers in Kansas. It is quite impossible to reconcile Reynolds’s celebration of Brown’s militant version of abolitionism with his defense in this book of Jackson as a racial moderate. One is left wondering whether Reynolds was attracted to Brown’s career simply because of its hopeless, useless violence, and the drama of his defeat.

“This period can be divided culturally into the pre-Jacksonian and Jacksonian phases,” Reynolds writes. “The dividing point between the two phases occurs around 1828, the year Jackson was first elected president and became a truly symbolic, and controversial, hero of the people.” Before 1828, Reynolds explains, the pre-Jacksonian writers Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper produced works under the influence of European models. After that date, American literature became more independent, reaching its enduring greatness under the leadership of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Whitman, and Melville.

We can agree; but tying this evolution to party politics doesn’t work. Cooper supported Jackson’s Democratic Party, and Irving accepted office under Jackson. On the other side of the divide, Emerson and Thoreau never identified with Jacksonian democracy, while Whitman quit the Democratic Party in disgust at its proslavery position well before publishing Leaves of Grass. Hawthorne was indeed a partisan Democrat, but took his literary inspiration from Puritanism, not Jacksonianism. Melville’s Ahab is a sinister embodiment of demagogy. It is surprising that Reynolds, a respected literary historian, puts forward such a simplistic political interpretation of literature.

Whatever usefulness Waking Giant might possess is vitiated by a multitude of factual errors, particularly evident when Reynolds is discussing political matters. The Monroe Doctrine did not actually arise “from a quarrel with England.” Andrew Jackson was not the first president to use the pocket veto. The Liberty Party was not the same as the Free Soil Party. Mormon prophet Joseph Smith was not arrested for polygamy, but for suppressing a critical newspaper in Nauvoo, Illinois, where he was mayor. Secretary of the Treasury William Duane was not “a supporter of the BUS [Bank of the United States]”; he opposed its recharter but declined to violate statutory law by removing the federal deposits from the bank in the absence of a finding that they were unsafe there. In listing Whig presidents, Reynolds includes John Tyler, who was expelled from the party, and forgets Millard Fillmore.

Citations are frequently ambiguous or not supplied at all, even for remarkable assertions such as this one: “Premarital pregnancy rates fell from 30 percent in the late eighteenth century to under 10 percent by 1850.” Reynolds’s latest book is, accordingly, not simply a failed effort but quite unworthy of the author of such fine works as Walt Whitman’s America (1995) and Faith in Fiction (1981).

For a similarly broad-based work, celebrating American cultural diversity in Whitmanesque fashion and more sympathetic to Andrew Jackson than I am myself, a much better choice would be Walter A. McDougall’s Throes of Democracy: The American Civil War Era, 1829–1877. The title is a quotation from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: “And sing me before you go the song of the throes of Democracy.” McDougall has his quirky likes and dislikes, which keep a reader engaged; he has new ideas on some subjects; and he provides information that is much more reliable than Reynolds’s.

McDougall is not in the least intimidated by current intellectual fashions. He is more critical of Andrew Jackson for destroying the national bank of his day than for his part in expelling the Indians from east of the Mississippi. He is surprisingly critical of Lincoln, whom he accuses of alienating Virginia by a premature call for troops to suppress South Carolina’s rebellion. He portrays an age in transition, when Americans too often deluded themselves with self-righteous pretensions, an age in which he finds parallels with our own, but not the simplistic ones of conventional historiography.

McDougall’s characteristically imaginative assessment of the two political parties of the middle period deserves quoting at length:

Who were the conservatives and who were the liberals in this second party system? If one adopts twentieth-century definitions it might appear that the libertarian Democrats were the conservatives and the statist Whigs the liberals. But in the parlance of nineteenth-century Britain, where the labels originated, the reverse would be true.

In regard to slavery, free-soil Whigs would appear the liberals and the Democrats supporters of a racist status quo. But in regard to workers’ rights as understood later in the century, neither party was “progressive.” In regard to ethnic and religious tolerance the Democrats would appear the liberals, since they embraced Catholics and immigrants. But in regard to education and social reform the reverse would be true.

The only way to get a grip on the growing divide among Americans in the mid-nineteenth century is to purge our contemporary notion of the political spectrum and try instead to imagine the ambivalent anxieties of a freewheeling people with one foot in manure and the other in a telegraph office.

McDougall’s juxtaposition of manure and a telegraph office is an inspired metaphor for the changes of the period he treats. Andrew Jackson arrived in Washington in a carriage in 1829 and left eight years later on a train. The revolutionary consequences of new technology in transportation and communications that transformed American life during the middle period can provide a better focus for historical writing than a personality cult focused on Jackson himself.

The term “Jacksonian America” is inappropriate and misleading. Jackson was a divisive figure who polarized people and whose policies as president proved as often harmful as beneficial. Taking Andrew Jackson to typify early-nineteenth-century America does a disservice to our country’s history, which has many interesting aspects and admirable people outside the orbit of Jacksonian Democracy (originally the name of the Democratic Party, not a general characterization of the United States). Most Americans today consider the abolitionists heroes, though Andrew Jackson hated and feared them. Other candidates for present-day honor include DeWitt Clinton, mastermind of the Erie Canal, built by the State of New York; Horace Greeley, crusading journalist; Horace Mann, advocate of state aid to the public schools that would create a literate citizenry; Lucretia Mott, Quaker feminist; and the black polemicist David Walker.

Jackson’s partisan rivals the Whigs, often disparaged simply as snobs who couldn’t reconcile themselves to equal rights, actually have a strong claim on our respectful attention. The Whigs (their name was the traditional one for critics of executive abuses in Anglo-American history) understood the benefits of economic development and wanted government at all levels to promote it. They, not Jackson, endorsed federal government intervention in the economy. When the stock market crashed in 1837–1839, the Whig leader, Henry Clay, declared the American people “entitled to the protecting care of a parental Government.” The Democrats, led by Jackson’s chosen successor Martin Van Buren, insisted that Washington observe strict laissez faire.

The American experience between 1815 and 1848 did much to shape the country we live in. Social reform, religious zeal, large-scale immigration, wild swings of the business cycle, wars brought on by executive power in the face of severe moral criticism—these and other issues bear a surprising resemblance to some we face today. They can well bear reexamination by historians and citizens who seek to understand the past and its effect on the present. Such a reexamination may reorient the conventional definition of a “Jacksonian” period and provide a new perspective on the politics of that time. Who knows, today’s liberals might find many of their sympathies engaged not by Jackson’s Democrats but by the Whig party of John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and the young Abraham Lincoln.

This Issue

May 28, 2009