Can a negotiatior for a Middle East settlement be both objective and produce results? Can a national negotiator ever be completely objective? How much does it matter? Dag Hammarskjöld, the UN’s famously principled second secretary-general, wrote personal guidelines for his task that included the following: “If, while pleading another’s cause, you are at the same time seeking something for yourself, you cannot hope to succeed.”1 A corollary for the Middle East might read: “And if you do not have materially substantial means of persuasion, you cannot hope to succeed either.”

In the early postwar years, disinterested international mediators were considered, especially by the United States, to provide the best hope for a settlement in the Middle East, and, in those relatively innocent days, they made considerable, if not decisive, contributions. Before he was assassinated in September 1948, the UN mediator in Palestine, Folke Bernadotte, was able to submit to the UN General Assembly a detailed proposal for a two-state solution that has now, sixty-one years later, reemerged as the basic objective of Middle East negotiations. His successor, Ralph Bunche, negotiated armistice agreements that ended the first Arab–Israeli war and provided a practical arrangement for an interim peace in the region, pending the conclusion of a permanent settlement. The conduct of both these mediators was generally recognized as living up to Hammarskjöld’s rigorous standards.

As the situation in the Middle East became more complicated over the years, it was increasingly clear that even the ablest and most objective international mediator lacked the necessary political, financial, and military backing to move the various parties toward a settlement. In the late 1960s the last of this breed, the highly respected Gunnar Jarring of Sweden, was unable, after intensive negotiations, to get simultaneous agreement by Egypt and Israel on peace between the two countries and the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Egyptian territory. That was finally achieved by President Jimmy Carter in 1978 in the Camp David Accords.

Since the Jarring mission, governments, and specifically the United States government, have become the preferred intermediaries for a Middle East settlement. The primary responsibility of a government is, naturally, the interest and well-being of its own country and people. This priority will inevitably be a major influence on the conduct of negotiations in a region that is critically important to the United States. Even disinterested expert proposals like the recommendations submitted to President Obama by the US/Middle East Project2 will, when and if they reach the official level, be subjected to all the crosscurrents, pressures, and controversies that swirl around Middle East matters in Washington.3

As Patrick Tyler puts it:

If history has revealed anything, it is that it takes American leadership, robust leadership that galvanizes the Congress and world opinion, to bring the two sides—Arab and Israeli—into a position where they have a chance to solve [their conflict].

That is one of the many great challenges that face President Obama. America’s conduct of Middle East peace negotiations will continue to be under the constant observation and criticism of all concerned. This inescapable fact of American leadership is the underlying setting for the two books under review.

1.

Patrick Tyler’s A World of Trouble: The White House and the Middle East—from the Cold War to the War on Terror would have made great source material for a Shakespearean cycle of historical plays about the postwar presidents of the United States and the Arab–Israeli problem. His book brims over with tragedy, tragicomedy, battles, intrigues and backstabbing, farcical episodes, deceptions and misunderstandings, and the use and abuse of power, force, and money. There are few, if any, heroes.

Describing the 2003 American occupation of Iraq as “the most current expression of a half century of costly miscalculations in the Middle East,” Tyler writes that in six decades “it remains nearly impossible to discern any overarching approach to the region” and that “American leaders have been unable to agree on a firm set of principles, a consistent set of goals, or a course of action that could bring peace and stability to the Middle East.” In each of the many wars or crises, “blindsided or flummoxed presidents” wondered why surprise and unpreparedness seem to be the normal condition for the United States government in relation to Middle East developments.

The result, in Tyler’s words, is a “record of vacillation, of shifting policies, broken promises, and misadventures, as if America were its own worst enemy.” Such an indictment could well also be addressed to the United Kingdom, the mandatory power in Palestine from 1922 to 1948. Ralph Bunche, who wrote the Palestine partition plan adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1947, remarked that “about the only subject on which both Arabs and Jews seem to be in agreement is that the British must go.”4

Advertisement

Tyler’s survey of each administration’s efforts and mishaps, often vastly complicated by the conflation of the cold war with the Arab–Israeli problem, is dramatized by vivid, and often personal, detail. This is one of those books where one constantly hurries to the endnotes. Tyler’s wide research—especially his access to telephone records—gives a sometimes shocking picture of how mood, temper, temperament, and personal ambitions and antagonisms all too often influenced important decisions in Washington during the seemingly endless crises of the Middle East.

2.

Tyler describes President Eisenhower’s handling of the 1956 Suez crisis in which he defended the principles of the UN Charter5 against three of America’s closest allies—Britain, France, and Israel—as his “finest hour.” In December 1960 Eisenhower first learned of the Israeli nuclear center at Dimona, which CIA Director Allen Dulles told him “cannot be solely for peaceful purposes.” A request for information only elicited a statement by Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion that Dimona was “designed exclusively for peaceful purposes” and that any allegation that Israel was making an atomic bomb was a “deliberate or unwitting untruth.” Such statements have a familiar ring today as the world worries about Iran’s nuclear activities. Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, received the same reassurances from Ben-Gurion.

Israel’s response to Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s 1967 demand for the withdrawal of the UN peacekeeping force from Gaza and Sinai and his move of Egyptian forces into Sinai was a simultaneous and devastatingly successful air attack on Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian airfields on June 5, 1967, followed by the occupation of Sinai, the Golan Heights, and the West Bank. The Israeli action took President Johnson by surprise. In the seventeen days between Nasser’s announcement and the Israeli attack Johnson had done little except to urge general restraint.

Here I think Tyler is unjust to UN Secretary-General U Thant, whom the United States and its Western allies later designated as scapegoat-in-chief for the Six-Day War. U Thant, alone among world leaders, went to Cairo to try to convince Nasser that although Sinai had been Egyptian territory for some four thousand years, it was a disastrous mistake to redeploy his newly Soviet-equipped army there and thus provide the justification for an Israeli invasion and occupation of Sinai in the name of self-defense. U Thant got no support in this effort, and subsequent Security Council meetings quickly degenerated into barren cold-war exchanges that had little or nothing to do with the impending disaster.6

After the Six-Day War, a new era of brutal Palestinian militancy began, including the massacre of eleven members of the Israeli team at the 1972 Munich Olympic games. There was plenty of evidence that Arab governments, and especially Anwar Sadat’s Egypt, were as determined as ever to recover the lands lost to Israel in the 1967 war—by diplomacy if possible, and, failing that, by force. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev certainly understood the danger of the situation and tried, at a meeting in San Clemente in June 1973, to persuade President Richard Nixon to cooperate with the Soviet Union in preventing another war. Nixon and his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger turned down Brezhnev’s urgent plea. Tyler calls this “a tragic failure of American diplomacy.”

In the late summer of 1973, UN military observers reported a large Egyptian military build-up on the Suez Canal, but both the CIA and Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir apparently thought that Sadat was bluffing. The successful Egyptian attack across the Suez Canal on October 6, 1973, came as a painful shock both to Israel and Washington.

After four days of battle Israel had lost five hundred tanks and fifty aircraft. Golda Meir mobilized nuclear forces, and Kissinger pressed for sending immediate military aid to Israel against the advice of Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, who maintained that such aid would be seen by the Arabs as helping Israel to hold on to the Egyptian territory it had captured in 1967.

The only hope of stopping the war would have been peace negotiations under the auspices of the two superpowers, Brezhnev’s idea that Nixon had rejected three months earlier. Kissinger, who, in Tyler’s account, comes out poorly both as a colleague of Nixon’s and as a strategist, apparently felt that Egypt could not be allowed the victory of getting Sinai back, because that would also be a victory for the Soviet Union. As Schlesinger had predicted, Nixon’s lavish provision of military supplies to Israel “triggered a major response from the Arab oil producers and prompted them to enforce an embargo that ravaged Western economies.”

The episode ended with a hair-raising crisis between the US and the USSR, when Israel, with Kissinger’s com- plicity, according to Tyler, continued to ignore a Security Council–ordered cease-fire in order to complete the defeat of the Egyptian army in Sinai. The Soviet Union, after another unsuccessful call for joint US–Soviet action, began moving airborne forces toward the Middle East, causing the US to activate the highest global nuclear alert ever declared, Defense Condition III. Recognizing the very great danger of the situation, the Security Council finally took practical action. The rapid deployment of a UN peacekeeping force (in less than twenty-four hours) to police the cease-fire in Sinai finally marked the end to this lamentable chain of events.

Advertisement

Tyler does not specfically mention Kissinger’s brilliant negotiation of the “disengagement agreements” between Israel and Egypt and Syria that were executed by the UN and subsequently stabilized the situation. (The disengagement agreement on the Golan Heights is still functioning pending an Israeli–Syrian final agreement.)

The Middle East Peace Conference met for a one-day session on December 23, 1973, to approve the first stage of these agreements but, with the exclusion of the PLO, to which the Arab governments strongly objected, it could go no further. In retrospect this seems a great missed opportunity and one that would not come again. In 1973 there were no Israeli settlements; and Islamic extremism had not yet become a divisive element of the PLO.

Jimmy Carter, Tyler writes, “was the first American president to come to office strongly committed to working for a comprehensive settlement of the Arab–Israeli dispute in the Middle East.” His secretary of state, Cyrus Vance, a public servant of great integrity, was also committed to that objective, which would entail including the USSR as co-partner and establishing a homeland for the Palestinians. Neither the Israelis nor the Arabs warmed to this idea, and Carter soon ran into all the trouble that a combination of Israeli opposition and cold-war obsession could create in Washington. Carter appealed to President Sadat of Egypt for his help, but Sadat’s later response—to go to Jerusalem to address the Knesset—left Carter “unhinged” and inactive for some time. Menachem Begin, who had become Israel’s prime minister in June 1977, reacted sullenly to Sadat’s courageous, and in the event suicidal, initiative, and Begin’s relationship with Carter steadily deteriorated.

At the Camp David summit convened by Carter in September 1978, his perseverance eventually converted days and nights of bitter recrimination and confrontation into the Camp David Accords, a separate peace between Egypt and Israel. In the final middle-of-the-night session, Carter was unable to fight off Begin’s last ambush—he would not pledge to suspend settlement building in the West Bank. With the world awaiting a successful outcome of the talks in the morning, Carter and Sadat had to choose between sacrificing the restoration of Sinai to Egypt or swallowing Begin’s bitter pill. They chose Sinai.

Ronald Reagan’s profound ignorance of the Middle East and the arro- gance and partisanship of his first secretary of state, Alexander Haig, grievously eroded Reagan’s credibility in the Arab world. The loss of 242 US servicemen in a terrorist attack in Beirut and the subsequent withdrawal of US forces also proved that the US was highly susceptible to terrorism. US support for Saddam Hussein in his war against Iran, tolerance for Saddam’s use of chemical weapons, and the surreal Iran-contra affair further fueled the astonished skepticism of much of the world. As Tyler puts it, “Only a crippled administration could have secretly joined both sides of the Iran–Iraq War, rationalized the use of chemical weapons, or abandoned Lebanon for blatantly political reasons.”

President George H.W. Bush reversed Reagan’s penchant for Saddam Hussein, whose 1990 conquest of Kuwait posed the urgent problem of the protection of Saudi Arabia. Operation Desert Storm—forty days of aerial bombardment and one hundred hours of ground battle—was ostensibly a success, tarnished by the fate of the northern Kurds and the southern Shia who responded to Bush’s call for resistance and were abandoned to the harshest of reprisals by the supposedly defeated Saddam Hussein. Bush and his secretary of state, James Baker, had a more balanced approach than their predecessors to the Arab–Israeli problem. The Madrid conference, co-chaired by the US and Russia in the fall of 1991 with all the parties including the PLO, created, for the first time, a comprehensive diplomatic process for the pursuit of peace in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton presided over the mutual recognition of Israel and the PLO on September 9, 1993, but personally took over the peace negotiations too late to achieve results. He was, Tyler writes tactfully, “driven more by domestic requirements and less by the real exigencies of the Middle East peace.” During Clinton’s presidency, which cov- ered the five years of the Oslo peace process, Israeli settlements in the occupied territories more than doubled, a development that enraged Arabs and encouraged the steady growth of Hamas and Hezbollah.

Tyler, whose chapter on George W. Bush is relatively short, considers that

Bush’s tenure appeared as a cynical opting out of the labor-intensive Middle East peace process…. His legacy in the Middle East would be defined as much by the forsaken mantle as by the blunder of an unnecessary war.

3.

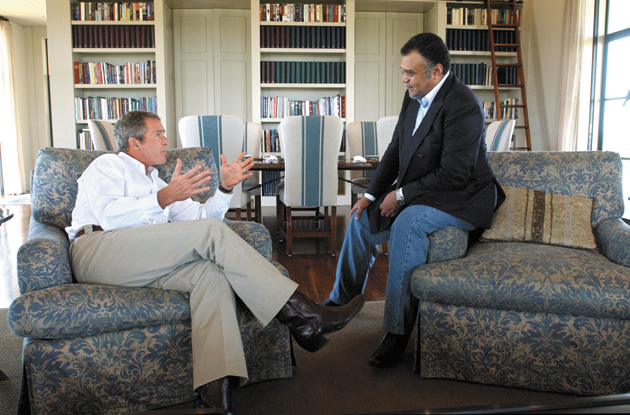

The most engaging character, as far as there is one in this tale, is the former fighter pilot Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the genial and long-suffering Saudi Arabian ambassador to Washington during four administrations. Bandar became the fixer, financier, enabler, adviser, rescuer, and, above all, shoulder to weep on for top US officials for more than twenty years. Bandar’s Washington odyssey is a striking measure of the unusual, not to say bizarre, atmosphere in which Washington’s engagement with the Middle East has often been carried on.

Tyler’s book opens in Bandar’s palace in Riyadh in 2004 with the now famous scene in which CIA Director George Tenet, suddenly aware that he is the designated scapegoat for the absence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and not adequately sedated by a sleeping pill, allegedly emerges from his bedroom in his underclothes, drinks half a bottle of scotch, denounces his enemies in Washington in unbridled terms, drinks more scotch, and then, to Bandar’s alarm, throws himself into the swimming pool where, grasping a large Havana cigar, he does imitations of Yasser Arafat and Omar Suleiman, the Egyptian intelligence chief.

On the day in 1982 when the White House announced Alexander Haig’s resignation, the Haigs were expected at a dinner at Bandar’s embassy.7 Haig asked Bandar to tell the other guests not to come and make it “just the four of us.” After dinner, Haig began sobbing uncontrollably and, like George Tenet twenty-two years later, railed at the White House for “setting him up.” Nineteen years later when another former general, Colin Powell, became exasperated with George W. Bush’s refusal to engage with the Israeli– Palestinian problem and his seemingly permanent tilt toward Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, “Powell…vented his frustrations during evening bull sessions with Bandar.”

“Bandar, you are the only person who can save me,” President Bill Clinton told the astonished Saudi ambassador. Clinton was obsessed with the prospect that Yasser Arafat, an Olympic-class kisser, would kiss him in front of the cameras at the signing of the Oslo agreements on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993. Bandar told Arafat that King Fahd wanted a display of dignity and poise at the ceremony, and that would mean manly handshakes and no kissing. Arafat protested that he wanted to show the affection of the Palestinian people for the new American president, but Bandar at last prevailed. Yitzhak Rabin also took preemptive measures against being kissed.

Bandar’s services were not a one-way street. He exercised extraordinary influence in Washington. On the day after September 11, when all civil flights had been banned throughout the United States, Bandar was able to arrange for two Boeing 747s to take off, carrying selected Saudi civilians back home.

Before the state dinner that was the climax of King Fahd’s 1985 Washington visit, the Saudis could not obtain the customary advance text of the President’s speech, and the King was reduced to asking Reagan, at the dinner itself, to let him see the text. He quickly discerned why it had been kept from him: Reagan’s speech ended with a strong appeal to the King to extend his hand to Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Fahd, furious, ordered Bandar to arrange with Bud McFarlane, Reagan’s national security advisor, that all of the President’s speech, except for the opening and closing formalities, be omitted. Astonishingly, Reagan agreed and improvised a warm and completely insubstantial speech instead. Next morning Bandar was able to tell McFarlane that Saudi Arabia would begin at once the payment of $2 million a month—twice what Reagan had requested—to the Nicaraguan contras.

Bandar’s missions were seldom dull. In April 1990, King Fahd sent him to Baghdad to find out if Saddam Hussein was really crazy. Saddam told him:

“When I am suspicious of a guy, I kill him.”

“How do you know if he is guilty?” Bandar asked.

“I look into his eyes and if I see it in his eyes, I kill him,” Saddam replied, terrifying Bandar with a cold-blooded gaze….

4.

Rashid Khalidi, in Sowing Crisis: The Cold War and American Dominance in the Middle East, presents an Arab view of the history covered by Tyler. The two writers are often in agreement. Khalidi, former director of the Middle East Institute at Columbia, is a Palestinian scholar and historian of Middle East affairs. His basic theme is that current conflicts in the Middle East were both shaped and exacerbated by the cold war.

Although both Desert Storm and the Madrid conference took place after the end of the cold war, Khalidi maintains that these assertions of unrivaled US power in the region had their roots in the perceived necessity to keep the Soviet Union out of the Middle East. He believes that their rivalry was far more important to both superpowers than the Arab–Israeli conflict itself or the attempt to achieve peace; the region and its states were, to them, proxies during the cold war in the “cold calculus of power politics.”8

It is, perhaps, idle to speculate whether the Arab–Israeli conflict might have been more easily resolved if there had been no cold war. Khalidi maintains that the cold war was more often than not a catalyst for Arab–Israeli conflict, with both superpowers providing vast quantities of weapons and manipulating regional rivalries to provide proxy cold-war battlefields. Occasionally the superpowers lost control of their proxies and were dragged into confrontations with each other, as in the 1973 war that brought them to the brink of nuclear confrontation.

Khalidi emphasizes the essentially unilateral nature, from Kissinger onward, of US policy in the Middle East, “meant primarily to establish the paramount position of the United States in the Middle East at the expense of the Soviet Union.” In a different ideological context, he describes the disastrous effects, especially in Iraq in 2003 and in Lebanon in 2006, of the George W. Bush administration’s “utterly unilateral vision of the international order.”

Khalidi gives credit to Jimmy Carter for making the first good-faith attempt at a comprehensive Arab–Israeli settlement and for proclaiming the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people rather than treating them merely as a refugee problem. However, the bilateral deal over Sinai at Camp David in 1978 left the Begin government free to “achieve its primary objective, of colonizing the West Bank with Israeli settlers, without hindrance.”

Khalidi’s catalog of American mishaps and errors painfully reflects the dismay of a highly intelligent Palestinian scholar. He describes the “War on Terror,” misleading and wrong-headed concept that it is, as having a “quasi-religious significance” for Bush and his neoconservative advisers, rather like the crusade against communism fifty years before. It was, he declares, psychologically understandable for American domestic reasons after the shock of September 11; but the efforts to execute it often created terrorists where there were none before. The constantly trumpeted slogan also served to justify starting two still-unfinished and very bloody wars and provided cover for an expansion of presidential powers that might otherwise have been strongly opposed.

“The Middle East,” Khalidi concludes bitterly, “is simply too important to the vital interests of too many people the world over to be left much longer to the sometimes brutal ministrations of a reckless, stumbling, delusional giant.” Under the Bush administration, moreover, the US was operating in a world without rules because

the framework of international law and institutions painstakingly devised at the end of World War II has been systematically disdained and degraded in part by the arrogant unilateralists who were in power in Washington for eight years, at times openly expressing their contempt for the United Nations, international law, and human rights.

Khalidi finished his book in the summer of 2008. It would be interesting to know his view of the efforts of the new administration.

5.

In his conclusion, Patrick Tyler writes, “America’s destiny in international relations is to play the role of a just, magnanimous, and stabilizing power.” That is more or less what Eisenhower succeeded in doing during the 1956 Suez crisis, and what Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush tried to do in the Middle East in 1978 and 1991 respectively. President Obama’s basic policy on the Israeli– Palestinian peace process is now being worked out and explained. He has appointed as his representative on the Middle East peace process a respected and successful negotiator who is the author of the 2001 “Mitchell Report on Israeli–Palestinian Violence.” George Mitchell is generally thought to be as near to objective and fair-minded as a negotiator can be.

Obama is insisting on a two-state solution as the basis for peace negotiations and has called for a freeze for all Israeli settlement expansion in the West Bank. The openness and level-headedness of his approach should at least reduce the paranoia that has sometimes confused attempts at peacemaking in the Middle East. Obama’s speech in Cairo was, among other things, an unprecedented attempt to clear the air with all those concerned with the peace process and to lay out the lines on which he proposes to assist in it.

How far this promising start will advance the prospect of peace remains unclear. The Palestinian leadership is hopelessly divided. The Israeli government of Benjamin Netanyahu has taken a hard line on peace talks and on vital issues like the freezing of settlement growth and the future of Jerusalem.9 But this is only the beginning of what must be hoped to be a new era in the pursuit of Middle East peace.

In July 1947, Ralph Bunche, who was about to draft the report of the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, wrote:

One thing seems to be sure, this problem can’t be solved on the basis of abstract justice, historical or otherwise. Reality is that both Arabs and Jews are here and intend to stay. Therefore in any “solution” some group, or at least its claim is bound to get hurt. Danger in any arrangement is that a caste system will develop with backward Arabs as the lower caste.

After sixty years of tumultuous and often violent developments, that still sums up fairly well a negotiator’s dilemma.

—July 14, 2009

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory

-

1

Markings ( Knopf, 1964), p. 114.

↩ -

2

A Last Chance for a Two-State Israel–Palestine Agreement: A Bipartisan Statement on US Middle East Peacemaking. The panel members were Zbigniew Brzezinski, Chuck Hagel, Lee H. Hamilton, Carla Hills, Nancy Kassebaum-Baker, Thomas R. Pickering, Brent Scowcroft, Theodore C. Sorensen, Paul A. Volcker, and James D. Wolfensohn.

↩ -

3

A just-published book, Myths, Illusions, and Peace: Finding a New Direction for America in the Middle East, by Dennis Ross and David Makovsky (Viking), presents a powerful and revealing series of reflections on the Israeli–Palestinian problem by the negotiator under both George W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Ross is now a member of the National Security Council staff.

↩ -

4

Letter to Ben Gerig of the State Department, July 23, 1947. Quoted in Brian Urquhart, Ralph Bunche: An American Life (Norton, 1993), p. 146.

↩ -

5

A simple way of being objective that is now used surprisingly rarely.

↩ -

6

I was closely involved with U Thant during this episode. We were all frustrated that there were no further practical options for the secretary-general unless the permanent members of the Security Council were prepared to put aside their differences and cooperate in removing the pretext for an Israeli preventive strike. They were not.

↩ -

7

The Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982 created a rift in Reagan’s cabinet between those who saw the Israeli attack as a dangerous blow to the US position in the Middle East and Secretary of State Alexander Haig, who, without informing the President, had aligned the United States with the Israeli invasion strategy. The 1982 Israeli intervention in Lebanon led to the emergence of the Iran- supported Shiite organization Hezbollah, now a fixture of Lebanese politics.

↩ -

8

Khalidi actually uses this phrase in defining the true nature of the League of Nations Mandate system.

↩ -

9

For a highly perceptive analysis of these problems see Hussein Agha and Robert Malley, “Obama and the Middle East,” The New York Review, June 11, 2009.

↩