1.

James Ellroy’s astonishing creation, the Underworld USA Trilogy, is complete. Its concluding volume, Blood’s a Rover, has just been published. The three long thrillers that make up the trilogy (American Tabloid, 1995; The Cold Six Thousand, 2001; Blood’s a Rover, 2009) present a brutal counterhistory of America in the 1960s and 1970s—the assassinations, the social convulsions, the power-elite plotting—through the lives of invented second- and third-echelon operatives in the great political crimes of the era. The trilogy is biblical in scale, catholic in its borrowing from conspiracy theories, absorbing to read, often awe-inspiring in the liberties taken with standard fictional presentation, and, in its imperfections and lapses, disconcerting.

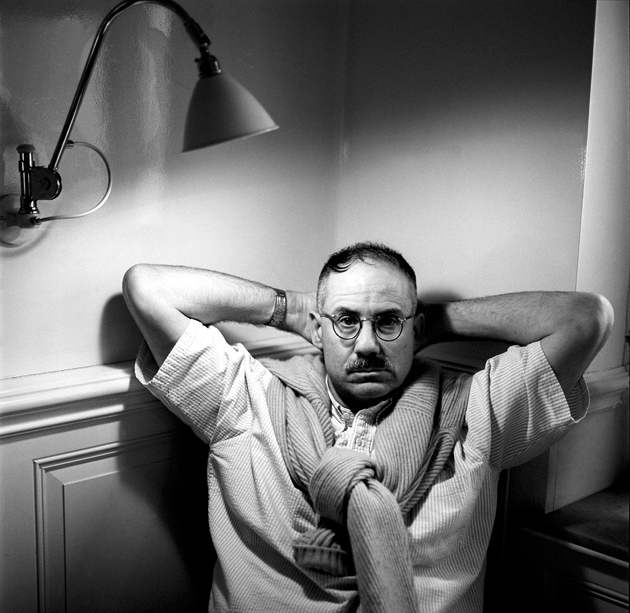

Ellroy, who is in his early sixties, is the celebrated, prolific, and popular author of a body of genre crime fiction, crime journalism, and a forensic memoir dealing with his own dark family history. His work has been made into movies and television shows, and widely translated. There are Web sites devoted to Ellroy, and he connects with his fans through Facebook.

The Underworld USA Trilogy is generally regarded as Ellroy’s magnum opus. It is unique in its ambitions, and proceeds at a level of art distinctly above that attained in his famously lurid and violent but more conventional books. It is a fiction unlike any other.

The Underworld USA Trilogy gives a literary answer to the question of what it was that so deformed the history Americans traversed in the 1960s and 1970s. As Ellroy presents it, a constellation of independent but collaborating power centers, pursuing sometimes identical and sometimes antagonistic objectives, was responsible. They include the secretive tycoon Howard Hughes, the Mafia, J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI, Jimmy Hoffa and his corrupt associates, and a disorganized but still potent consortium of KKK and other white supremacist groups, as well as international narcotics producers. Hoover is the sole unmoved mover. Howard Hughes is insane, Hoover is getting there, and it is his strategies that dominate all. Hoover, like the KKK, is phobic about blacks and Communists. The objectives of the other players are largely pecuniary.

The forces in opposition to this network of villains include Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, an inchoate pro-Castro left afflicted by divisions over the question of violence, and, later, a Black Power movement in which violence has become accepted policy. Also in the opposition but compromised by their family’s power intrigues in the past, and by their own personal weaknesses, are the Kennedy brothers.

Agents provocateurs abound, ancillary murders occur, people switch sides, ghastly errors are made. This chaos of mismated plotting yields the great assassinations of the period: John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Robert Francis Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. (Cases have been made for expanding this marquee death list to take in Malcolm X and Walter Reuther.) Flowing from the assassinations are the race riots, the destruction of the black nationalist movement, the machinations of COINTELPRO, and the election of Richard Nixon, pictured as a pawn of both Howard Hughes and the Mafia.

Ellroy, it has to be said, is fairly conventional in his selections from the fantastic richness of available conspiracy theories, and the ones he chooses, he trims up for his own purposes. The JFK hit is the combined work of the Mob, rogue CIA, Cuban exiles. The RFK hit is Mob. The MLK hit is FBI, Klan. Marilyn Monroe is left on the cutting room floor. Oswald is only a dumb patsy. The Mafia does the lion’s share when it comes to organizing the murders. From the loose ends of the Garrison investigation only the sinister Guy Bannister, an ex-FBI agent in New Orleans, survives to play a role as the recruiter of Oswald.

Unde malum: Where does evil come from? In Ellroy’s renderings, Hoover and the Mafia bosses are the sources of evil most at issue. Our understanding of the work of these central evildoers is reinforced by constructed documents—supposed wiretap transcripts, confidential memos, telexes, even journal entries. How close does the reader get to the inner life of these devils (who are not accorded opportunities to define their inner selves) through these devices, or via the conversations they have with the main characters in each volume? Hoover’s obsession with homosexuality, his own included, is conveyed pretty clearly, but surprisingly there is no reference to another personal sensitivity of his: he was aware of rumors that he was of mixed-race background and was enraged at any allusion to this supposition. Ellroy’s Hoover evinces a brittle nastiness, which is widely understood to be true of him. The Mob guys have very good lines, wit (much more wit than is evident in the real wiretap transcripts that have been left to us), and pretty good English. That’s about as close as we get to their minds.

Advertisement

But Ellroy’s idea of building, on the half-lives of secondary players caught in the web spun by others, a cruelly resonant reconstruction of a political hell is inspired. Other writers have worked in this field, of course. I think of Richard Condon (Winter Kills) and Don DeLillo (Libra). These are notable works, but they are limited to the JFK assassination and are, in essence, whodunits focused on the principals in that one case.

2.

In American Tabloid, the first volume of the trilogy, the main men—the three characters with their own points of view—are Kemper Boyd and Ward Littell, both FBI-connected, and Pete Bondurant, an ex–LAPD cop, now a freelance fixer and hoodlum working for the mob and Howard Hughes. Only Bondurant is a congenital thug. The other two have personal reasons (blackmail by Hoover, in one case) for staying with the Bureau as it turns toward murder. The JFK hit happens, but sloppily.

Two of the JFK-kill conspirators (Littell and Bondurant) survive into the second volume of the trilogy, The Cold Six Thousand. They, along with a Las Vegas cop, Wayne Tedrow Jr., on detached duty, are detailed to solidify the cover-up that followed the hit. They have a list of incidental witnesses to aspects of the plot who must be eliminated. Littell’s formerly positive feelings toward Bobby Kennedy have reversed into enmity: in researching the Mob, he has discovered that Joe Kennedy Sr. was a charter founder of the Teamsters’ Central States Pension Fund, a primary cashbox for the Mob. A plot develops to kill RFK: Littell’s earlier pro-Kennedy feelings revive, but too late. RFK is hit, ostensibly by a Mob patsy, Sirhan Sirhan.

Blood’s a Rover follows Wayne Tedrow Jr., Dwight Holly (an FBI “roving agent” with plenipotentiary powers), and Don Crutchfield, a peeping Tom and private investigator with an insatiable curiosity about the plots he brushes up against. J. Edgar Hoover, now in serious mental decline, orders a final campaign against the black nationalists. Plots, counterplots, and the search for the perpetrators of an unsolved armored car heist intermingle.

Two female characters, women of the left, move into the foreground and are entangled in relationships with Dwight Holly arising out of his infiltration activities. Tedrow dies. Holly is shot by a rogue cop. He is avenged by one of his lovers. The action hops jaggedly around, from LA to Las Vegas to Santo Domingo to Miami. There is a mordantly upbeat conclusion.

For those who want to read Blood’s a Rover on its own, there is a quick summary of the basic plotlines of the previous two books on pages 16–19. Blood’s a Rover both clarifies and complicates the question of what the trilogy project is really trying to say. But before looking more fully at the book, I want to say something about the genuinely remarkable manner in which this series is written. For a time, the tag Avant-Pop was attached to a certain kind of avant-garde writing, but that’s not right for Ellroy. Nor is Avant-Pulp. Whatever it should be called, the literary experience it provides is unique.

James Ellroy’s brand of extreme writing is fun to read. At its best, it could be addictive. The stories are told in a uniform, crazed, modern American vernacular, and with such breakneck speed, hairpin plot turns, compression, and telescoping of events that the reader needs to stop and rest from time to time. The standard noir subject matter of killings, beatings, and acts of revenge is all here, but the incidents are so closely packed and described with such loving attention to the injuries suffered that it’s hard not to feel that some limit of what the reader can bear is being toyed with:

He shot them in the back at point-blank range. Small-bore exit wounds —the cleanup wouldn’t be that big a deal….

Fulo smashed their teeth to powder. Pete burned their fingerprints off on a hotplate.

Fulo dug the spent rounds out of the wall and flushed them down the toilet. Pete quick-scorched the floor stains—spectrograph tests would read negative.

Fulo pulled down the living-room drapes and wrapped them around the bodies. The exit wounds had congealed—no blood seeped through.

In order to speed the flow of the prose, Ellroy tries almost everything. He’ll save two words by saying that a building is “lake-close” rather than that it stood “close to the lake.” One-sentence paragraphs take over. So do sentence fragments and sentences whose elements are broken up by slash marks. Dashes proliferate. The past perfect tense seems to evaporate and is replaced by the simple past tense to a degree that makes it difficult to figure out when exactly something is happening.

Advertisement

The standard noir product is tense and terse and tough by nature, and in fact the first volume reads like a supercharged variant of the recognized detective thriller. But in The Cold Six Thousand, the experiment is carried to new limits of charged compression:

Pete broke three C-notes. Pete glommed sixty five-spots.

He grabbed a scratch pad. He wrote down his phone number sixty fucking times. He hit a liquor store. He bought sixty short dogs. He grabbed his sap and drove to West Vegas.

He cruised in slow. He wore the sap. He held his automatic. He saw:

Dirt streets. Dirt yards. Dirt lots. Shack chateaus abundant.

Tar-paper pads with cinder-block siding. Beaucoup churches/one mosque. ALLAH IS LORD! signs. Allah signs revised to JESUS!

Lots of street activity. Jigs cooking bar-b-que in fifty-gallon drums….

Shouts overlapped—more rebop/ more jive. Pete yelled. Pete displayed charisma. Pete restored calm.

The last volume of the trilogy is toned down.

In each novel, Ellroy employs the free indirect mode (identified third person) throughout. In each, there are three lead characters and a point of view is locked to each one. But the narrative style does not adapt to the various backgrounds and temperaments of these characters. A shared voice is shouting the story in a racist, homophobic, profane, utterly unchecked vocabulary. How can this be right for all these characters? Who’s telling this story? I kept asking myself. The lead characters are various. Some of them are colgrads, including a couple of lawyers and a Ph.D. chemist. Some singularities surely ought to surface here and there. Why in each of the different points of view is the southern regionalism “boocoo” used for beaucoup? Why the flurries of French words and phrases? For Christ sake, who is telling this story? I wanted to know. It’s usual for the omniscient observer/reporter to be neutral, “an ideal observer.” In the final volume, a partial rationale for the point-of-view oddities is provided, but for me it didn’t work. I set my irritation to the side, though, and kept reading, going along.

Here’s the overriding achievement of the Underworld USA Trilogy: Ellroy elevates you to a fever-dream state. Once you have given yourself to the story, decided to overlook certain obstacles to the conspiracies and to forgive an occasional overreliance on coincidence or investigative good luck, and gone along with his adventures in prose, you feel yourself present for a time in an authentic and palpable circle of hell.

3.

Blood’s a Rover starts out feeling very much as though it’s cut from the same cloth as the previous volumes, but there is a change: a redemptive motif glimmers through all the blood. I had become acclimated to an action environment that might well have been called the Upper Depths, where lives predictably ended bleakly and horribly. So far, the trilogy had been a straight chronicle of individual failure. It was like life! Only the top malefactors of the piece get what they thought they wanted, before coming to their own unpleasant ends: Hoover, Hoffa, Hughes. So it goes…. We are all patsies, ultimately, he seemed to be suggesting. And now, quite unexpectedly, the shadow of redemption.

This is the set-up: the main characters—Wayne Tedrow Jr. (Hughes, Mob), Dwight Holly (FBI), and Don Crutchfield (two-bit PI)—operate circa 1968–1972 in orbits around various interesting projects. Hughes wants to take over Las Vegas and the Mob wants to sell it to him and secretly retain control of the profits through skimming. The Mob also wants to establish a new offshore gambling mecca in the Dominican Republic. Hoover is scheming to disable the post-MLK Black Power movement.

Turf wars rage over control of the international narcotics traffic (the CIA is a chief combatant). Stirred in are a clutch of strictly personal quests and vendettas, like finding a lost son, securing decent girlfriends, and solving the mystery of a 1964 armored car heist. The chief characters are heterosexual alpha males, strong, resilient, and resourceful. They recover from beatings as quickly as they throw off the effects of alcohol and drugs, and repeatedly return to the fray. These attributes are of course standard for noir heroes.

New here is the late eruption of green shoots of conscience among the characters. All three of Blood’s a Rover ‘s lead players are emerging from deep-right political conditioning. The growth of conscience is uneven among them. Tedrow, for example, the parricide offspring of a Klan/Mormon hate- merchant, arrives at the conclusion that he must only kill criminal black people. He falls in love with a black woman, the union-leader widow of a black preacher in whose death he is implicated. Infiltration activities bring Dwight Holly into contact with the first up-front, concrete representatives of the left: two women, Karen Sifakis and Joan Rosen Klein. Nascent sympathies for left causes begin to mess things up for Holly, and Crutchfield, too. Love intrudes.

Joan Rosen Klein, described in a cover note by Ellroy to the advance reader’s edition of Blood’s a Rover as his “greatest female character: The Red Goddess Joan,” is a sort of professional revolutionary. She is, we are told, in her “early forties, [with] dark gray streaked hair, glasses, a knife scar on one arm.” She is unattached, bisexual, and hot (so is Karen Sifakis). She has been everywhere that counts, pursuing the revolution: Algeria, Cuba, the Dominican Republic. According to the FBI dossier on Klein that we get a look at, she has consorted with anarchists, Communists, Trotskyists, the Weather Underground, followers of Daniel De Leon…in short, everybody. She is attempting to bring white radical groups into close supporting relationships with the black nationalist movement, her candidate for the present vanguard force for the revolution.

Karen Sifakis, an itinerant college professor, a mother, married but living only intermittently with her husband, is a comrade and friend of Joan Klein. Sifakis is a little younger. Dwight Holly’s infiltration program involves trading favors (for example, cleaning up FBI files that might be damaging to friends of either woman) for information on pending criminal activities by two emerging black nationalist groups. Karen Sifakis’s Quaker-tinged revolutionism permits only property destruction. Not so Red Goddess Joan’s ideology. In nineteenth-century French radical circles, she would have been labeled a catastrophard.

Joan Klein and Dwight Holly cooperate with each other because they share an interest in disseminating heroin. Holly, under Hoover’s instruction, is moving heroin to the black nationalists so that they will criminally self-destruct. Klein also wants heroin passed to them. She feels that establishing a heroin culture in the black community will somehow result in successful revolutionary chaos. This sounds amazingly dumb, but really it’s what she wants. From her journal:

THE FBI WANTS THE BTA AND MMFL TO MOVE HEROIN. THEY BELIEVE THAT IT WILL EXPOSE BLACK NATIONALISM AS INHERENTLY CRIMINAL AND REVEAL BLACK PEOPLE AT LARGE TO BE INHERENTLY DEPRAVED. THE FBI’S SHORT-TERM GOAL IS A SEDATED BLACK POPULACE; ITS LONG-TERM IS THE PERPETUATION OF RACIAL SERVITUDE. I WANT THE BTA AND MMLF TO MOVE HEROIN. I WILL RISK THE SHORT-TERM PROBABILITY OF SQUALOR IN FERVENT HOPE THAT THE SUSTAINED DEPRAVITY OF HEROIN WILL LEAD TO A RICH EXPRESSION OF RACIAL IDENTITY AND ULTIMATELY TO POLITICAL REVELATION AND REVOLT.

Dwight Holly falls in love with Klein and Sifakis at the same time.

The melodrama continues as before —killings, torture, dismemberments, betrayals, bombings, cover-ups. Sympathy for Hoover’s victims grows in Tedrow: “I’m going Red,” he thinks. Holly finds his new sympathies taking him dangerously close to defection just before he is shot to death (by one of his two lovers). At the end, the left wins a kind of hobbled, partial victory. Large helpings of ill-gotten Mob gains circuitously wind up in the hands of Klein and Sifakis. The presumptive onward careers of these women are intended to carry a message of hope. In fairness to readers I won’t say more about this, but the last couple of pages of Cormac McCarthy’s post-Armageddon novel, The Road, came to mind.

And finally, the metamorphosis of PI Don Crutchfield points toward hopeful things. He becomes a documentarian of the troubles. He compiles a detailed indictment that, when released into the world, will forever shame the guilty. Luckily, he becomes rich as the owner of a large detective agency specializing in validating (or not) allegations of scandal for the tabloid press. He develops an avocation as a finder of lost persons for the poor and deserving. His services for this work are provided gratis.

4.

Incisive portraiture is not Ellroy’s strong suit. Characters often act impetuously and seem confoundingly immune to sensing the inevitable consequences of things they do. The representatives of the rogue CIA are so weakly sketched as to be almost spectral. The most strongly sketched characters are the Mob bosses, but there’s nobody in these books anywhere near as deeply conceived as, for example, Norman Mailer’s James Jesus Angleton in Harlot’s Ghost.

As for Ellroy’s portrayal of the left, it suffers from an impressionistic lack of specificity, and when it essays specificity it is often goofy. For example, the late Bayard Rustin, the heroic pacifist civil rights veteran, is portrayed as a witting receiver of Mob money to support the work of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The transaction is arranged by the FBI for the purpose of gaining potential blackmail leverage. This is a notional, not to mention insane, bit of casting. (And friends of Bayard, myself included, are still around. His FBI files, which have been released, contain nothing that would make this conceit remotely thinkable.)

Finally, I decided I could live with this as a bit of clumsy synecdoche that worked well enough for the novel’s needs. And in truth, there was plenty of pure adventurism afoot in the left, as nobody can deny.

The left in which Red Goddess Joan and Karen Sifakis circulate is an odd environment, one without papers, parties, publications, leaders and their fandoms, or intraleft polemics. The only left thinker alluded to is “Franz” Fanon (his first name, Frantz, routinely misspelled). It’s a red blur inhabited by would-be citizens of societies in the mold of Fidel Castro’s brave little police state. Even in this romantically adventurist realm, there are no Maoists around.

The out-of-left-field rigmarole around Bayard Rustin is not pernicious so much as it is a malfunction of a device the author uses to jazz up the continuity, by giving cameo parts to celebrities of the period—in hopes that certain private activities of theirs, real or imagined, will tend to intrigue the reader. John Wayne was a cross-dresser, Sonny Liston was an enforcer for petty hoodlums, Sal Mineo was a murderer, Burt Lancaster was a closeted bisexual….

Dwight laughed.

“Anything else I should know?

“…Johnnie Ray sucks dick in Ferndale Park…Lana Turner dives dark sisters ca 1954…Liberace’s all-boy cathouse…Scopophile Danny Thomas, nympho Peggy Lee…Muff-diver Sol Hurok…Masochist…James Dean—“The Human Ashtray”…Ava Gardner and Redd Fox. Jean Seberg and half the Black Panthers….”

This sort of thing catches a reader’s attention. What Ellroy has done is take on-the-record allegations (stuff from the back files of Confidential magazine and items from sensational postmortem star biographies), tart everything up, and, when it suits the story, invent.

The Underworld USA Trilogy is a gizmo that works to induct the reader into a paranoid fantasy state, a temporary one reinforced powerfully by its points of contact with terrible events whose complete explication has not been fully achieved, at least in the judgment of a great many people. Large percentages of the public believe that the great assassinations of the 1960s were the result of machinations involving unknown groups and individuals. The residual popular skepticism about official history in this area is a resource that has been brilliantly exploited in this work. (Whether James Ellroy is personally attached to any of the reigning conspiracy theories one doesn’t know, and it doesn’t matter.)

I read the trilogy with a distinct, strong, and rather obscure pleasure, asking myself why, as I went along. I thought at first it must be related to why I like the Parker crime novels by Donald Westlake, which also feature an utterly conscienceless but superbly competent professional thief and killer and are also written in a minimalist style—though nothing like as extreme in its minimalism as Ellroy’s novels. I wondered if it must be tonic in some way to slip yourself into the personae of fearless sociopaths and then come out of it. But the Parker novels are short, like spasms, requiring nothing like the commitment that Ellroy demands. And the Parker stories are not concerned with large political questions. Reading Ellroy is not like reading Westlake or anyone else.

The Underground USA Trilogy is a major achievement in high parody. The peak of that achievement is reached in volume two, The Cold Six Thousand, which can fry your brain. There are plenty of secondary pleasures to be had in bumping through the trilogy’s manic rendering of the conspiracy topos, like watching the noir genre pushed way beyond its customary uses. Ellroy, in this huge endeavor, has found the right medium in which to tell the story of our recent time of troubles. That time was tragic, it hurts to think about it, and the toxins produced by the great assassinations are still draining into American life. It’s possible that it takes an obscene, raw, mighty parodic work like the Underground USA Trilogy to bring that time into literature.

This Issue

October 22, 2009