“Did you ever see Jefferson?” George Hurstwood asks Sister Carrie as he leans toward her in the Chicago theater to which he’s invited her and her “husband,” Charlie Drouet; “He’s delightful, delightful.” And when Hurstwood reports to his wife that the play was very good, “only it’s the same old thing, ‘Rip Van Winkle,'” every contemporary reader of Sister Carrie would have known exactly what he was talking about. Long before 1900, when Dreiser’s novel was published, Joe Jefferson was the most famous actor in America, and the richest. He was also the most beloved, his unparalleled genius for blending humor and pathos having endeared him to the entire national audience.

Yet it’s hardly surprising that today he’s completely forgotten: Who can remember the names of any American actors of the nineteenth century, except perhaps Edwin Booth and his notorious brother, John Wilkes? What’s surprising is that within the current decade, two scholarly yet engaging full-length biographies of Jefferson have appeared. In retrospect, though, you can see why two respected academics—Arthur Bloom (Joseph Jefferson: Dean of the American Theatre) and Benjamin McArthur (The Man Who Was Rip Van Winkle)—would choose to write about him. Joe Jefferson is not only a fascinating figure but the perfect vehicle for tracking the history of nineteenth-century theater in America. In a sense, his history is its history.

To begin with, acting was the family trade: he was the fourth generation of Jefferson actors. His great-grandfather, named Thomas Jefferson, was an English lawyer-turned-performer who was a protégé of the great David Garrick. His grandfather, the first Joseph Jefferson, emigrated to America and became the leading comedian in Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theatre, the nation’s most highly regarded playhouse. His father, the second Joseph, although a less resourceful actor, was a talented scenic artist. His mother, Cornelia, had been a very successful singer whose son by a first marriage, Charles Burke, was to become a great stage favorite. And there were sisters, cousins, and aunts in the business, as well as brothers and uncles—it was a clan, a tribe, a dynasty.

It’s natural, then, that Joe the Third, born in 1829, could confidently report sixty years later that “whenever a baby was wanted on the stage, either for the purpose of being murdered or saved, I did duty on those occasions.” At three, having fun backstage, he so charmingly and accurately mimicked the famous T.D. Rice, who had more or less invented the minstrel show, that Rice secretly got him up in blackface and dumped him out of a sack onto the stage while singing, “O Ladies and Gentlemen, I’d have you for to know/That I’ve got a little darky here that jumps Jim Crow.” Laughter, applause, and a rain of coins were his rewards—and these were the rewards he would go on assiduously seeking for the next seventy-odd years. At six he received his first mention in a review: he was little Alexis in a melodrama called The Snow Storm in which he cried out “Mother, Mother” to the offstage heroine, “Lowina of Tobolskow,” before freezing to death in a savage Siberian blizzard.

The fortunes of the Jefferson tribe began to erode when Joe’s grandfather lost his popularity, quit Philadelphia, and died, disheartened, not long afterward. The family troupe, lacking its star, tried New York, Washington, Baltimore, but by 1838 was forced to head west to the new boomtown of Chicago (population: four thousand) where family connections were waiting to welcome them. Through the next few years, the Jeffersons ranged the Midwest, reduced to a group of itinerant players, and eventually proceeded down the Mississippi. Within days of arriving in Mobile, Joe’s father died of yellow fever. Joe, at thirteen, and his younger sister were now the chief breadwinners, acting, singing, dancing in almost every performance, while Cornelia opened a boardinghouse to help make ends meet. But soon the Jefferson company ceased to exist, and the mother and two youngsters joined another itinerant company, which, having “constructed a barge, using scenery as a sail,” floated down a series of rivers to the Mississippi. Things got so bad that at one point the family and all its trappings were abandoned on a lonely road because they couldn’t pay the waggoner.

In 1846 they were in Texas, wary of Comanche raids, until during the Mexican War they followed Zachary Taylor’s army to the filthy, lice-ridden, dangerous town of Matamoras, where loud, drunken soldiers were demanding to be amused. (Some of them were pressed into service as players: Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant was rehearsing Desdemona until a real actress turned up to relieve him.) When the army moved on, the Jeffersons were stranded, Joe and an actor friend running a cigar stand until they managed to get back to New Orleans on a government boat.

Advertisement

In his memoirs, Joe drapes a veil of nostalgia, even romance, over this turbulent decade, but there was nothing romantic about his father’s death, the family’s desperate attempts to establish a new footing in the theater, and the anxieties of an impoverished, itinerant life. What saved them was the web of family connections and loyalties that yet again came to the rescue.

It was Joe’s beloved half-brother, Charles Burke, who proved to be the lifeline, summoning them all to join him in Philadelphia where he was already a successful young actor installed in a first-rate company. Joe had grown up as a precocious all-purpose entertainer; now, at seventeen, he began his serious apprenticeship to his art, slowly moving up the pecking order of the traditional stock company. He was already conspicuous for his ambition: from the first he saw himself as a potential star, just as from the first it was obvious that he had talent—as well as that essential quality for an actor, the ability to please. Yet it would take another decade of persistent hard work, false starts, and good luck before he became a name to be reckoned with—a star attraction if not quite a star.

By the late 1850s, Joe was an established leading comedian. He was also a married man. At the age of twenty-one, he had married a young actress with whom he quickly had six children, two of whom died as babies. In his autobiography, he never gives her name (Margaret Lockyer): “If I dwell lightly upon domestic matters, I do so, not from any want of reverence for them, but from the conviction that the details of one’s family affairs are tiresome and uninteresting.”

He was far more forthcoming about the great blow that had struck him in 1854, when Charles Burke died (of tuberculosis) in his arms, murmuring “I am going to our mother.” Joe’s love and admiration for Charles never wavered—although “only a half brother, he seemed like a father to me”—and he always maintained that if “my brother Charley had only lived, the world would never have heard of me.” Typical Jefferson self-deprecation, yet obviously heartfelt. Needless to say, Joe’s oldest son had been named after Charles.

By this time, Joe had begun evolving his near-revolutionary approach to character acting: again and again he would invest a one-dimensional farcical character with a simple and appealing humanity. It was a new brand of realism that critics as well as audiences came quickly to embrace and cherish. You laughed at Joe Jefferson, but it was a laughter of appreciation, not mockery.

His big breakthrough came when he joined a prestigious New York company and in 1858 was instrumental in launching a new comedy—Tom Taylor’s Our American Cousin. Joe played Asa Trenchard, the cousin from Vermont, who turns up in England and sorts out all the family problems as well as finding true love with a milkmaid who happens to be an heiress. The stage Yankee was traditionally a stock comic character with uncouth manners and mannerisms, good for a derisory laugh. Contemporary reviews underline that Joe played Asa with rough dignity and warmth, demonstrating Yankee common sense rather than Yankee eccentricity. The heart of gold—a Joe Jefferson specialty—shone through, and Our American Cousin achieved an almost unprecedented run of 139 consecutive performances (only Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Drunkard had run longer).

A streak of other hits followed: Dion Boucicault’s Dot, an adaptation of Dickens’s The Cricket on the Hearth, in which he played Caleb Plummer, the lovable but forlorn old toymaker; a version of Nicholas Nickleby in which his Newman Noggs, Ralph Nickleby’s clerk, became the central character; Boucicault’s sensational abolitionist melodrama The Octoroon, whose final line (at least in the version Jefferson preferred to play) he delivered as the heroine expired: “Poor child; she is free.”

Finally, and fatefully, in 1860 Joe happened to reread Washington Irving’s famous tale of Rip Van Winkle and realized that the character of Rip was tailor-made for him. There had been at least ten previous stage versions, but none of them had really succeeded in dramatizing Irving’s narrative effectively. Tinkering with the text, Joe took the crucial step of making the encounter between Rip and the ghosts of Hendrik Hudson and his crew the heart of the play. “I arranged that no voice but Rip’s should be heard. This is the only act on the stage in which but one person speaks while all the others merely gesticulate.” Convinced that he had a career-changing hit, he toured Rip through the Northeast, but the expected triumph didn’t materialize. Perhaps only he himself could imagine at this point that he had in his grasp what would become the most popular male role of the century.

Advertisement

In the spring of 1861, a concatenation of events led to a decisive moment in Joe’s life. Twenty-eight-year-old Margaret died in March, leaving him with four children to raise; his own health was a concern, since like his mother and half-brother he had weak lungs and a predisposition to tuberculosis; Rip hadn’t prevailed—his route to official stardom was blocked. But most important, the Civil War was breaking out, and he intended to play no part in it. After his death, a friend wrote:

Early in 1861 Jefferson came to me and said: “There is going to be a great war of sections. I am not a warrior. I am neither a Northerner nor a Southerner. I cannot bring myself to engage in bloodshed or to take sides. I have near and dear ones North and South. I am going away and I shall stay away until the storm blows over.”

It certainly rings true that Joe would not take sides if he could avoid it—his entire life was spent attempting to please everyone and offend no one. No surprise, then, that on June 1, 1861, seven weeks after the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, he left New York for California, taking with him ten-year-old Charley and leaving behind, with his late wife’s parents, the other three children, whom he would not see again for five years.

He was to recall the California experience (disappointing reviews, disappointing box office) as “an unmistakable failure,” and after four months, he made the decision to move on to Australia, where from the first he enjoyed a sensational success. During his initial stay in Melbourne, for instance, he played for 164 nights, and as Charley was to write, “We just simply coined it. It was like a mint.” Our American Cousin, The Octoroon, Newman Noggs, Rip, Bob Acres in The Rivals—it was the old repertory, plus a few novelties, including a stab at Bottom. Season by season he was achieving greater mastery of his craft, while piling success on success.

A critic in Australia who came to know Joe well left us in his journals an appealing portrait of him that helps explain his lifelong popularity:

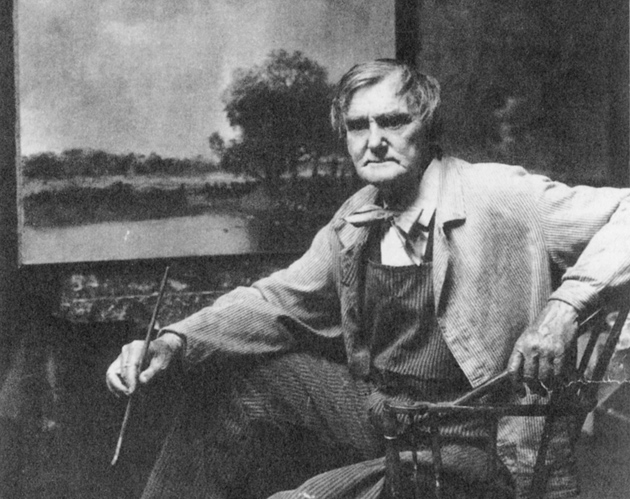

Joseph Jefferson about 36; slight & consumptive, with a small, sharp, eager face; forehead very prominent above eyes, soft brown hair, Napoleonic chin, & a quick bright eye, full of expression. One of the most unassuming men, charming companions and most finished comedians I ever met with…. Nothing of the actor about him off the stage; none of the professional envy & jealousy; fond of hunting, fishing and sketching.

When father and son finally left Australia in April 1865 they headed for England, not America (and the other children). Stopping along the way in Callao, Peru, they heard the latest news: “Oh! The war—that’s all over; the South caved in and Richmond’s took.” They also learned that President Lincoln had been assassinated by John Wilkes Booth in Ford’s Theatre in Washington. “Father tottered,” Charley would write,

and I believe he would have fallen had not the captain and I caught him. He was as white as a sheet, and for a minute trembled like an aspen. He and Wilkes Booth had been friends…. I can’t recall the time I ever saw father so moved as that information moved him.

No wonder. Not only was Booth a friend, but his brother, the great tragedian Edwin, had been Joe’s closest friend since early manhood and Ford was yet another old friend and colleague. The play being performed was, of course, Our American Cousin.

Yet in Joe’s memoirs there is no mention of the assassination. As Arthur Bloom puts it:

Once again, he was covering his tracks. In 1888, twenty-three years after the war’s end, Jefferson was not going to allow himself to be associated with the man who had shot Lincoln. It was bad for business.

Joe came away from Australia a rich man. He came away from England a great star—at last, at the age of thirty-seven, he had received the validation he had always longed for. It was Rip that did it for him. Arriving in London, he hired the hit-maker Boucicault to doctor the play, and Boucicault convinced him to make a critical change: to present Rip in the first act as a young, merry, energetic fellow, not a cranky and disappointed man approaching middle age. The resulting contrast between the young Rip and the old Rip gave Joe an irresistible dramatic line for the role. It was pointed out that the transformation after only twenty years of this young happy-go-lucky idler into a Lear-like old man with a flowing white beard made no sense, but Joe’s art and lovability conquered disbelief.

London took Rip, and Joseph Jefferson, to its heart, a typical review (this one from the Times of London) calling him “one of the most original…and finished actors ever seen upon any stage.” He and the play were so established there that he was able at last to send for his other children, and he was as popular in person as on stage. (Among the guests at a celebratory dinner after the final London performance of Rip were Dickens, Thackeray, and Wilkie Collins.) When he returned to America after a year in London, his English reputation preceding him, it was as an established star, and Rip quickly grew into a national institution. The eternal touring—and the eternal gush of money—had begun: his fees were unequaled in the business, because his box-office results were unequaled. The role, Bloom remarks, had become an American icon, the editor of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine likening Joe’s Rip “to shrines at which worship is imperative like the Pieta in St. Peter’s.” Just as the heart-stopping melodrama of Uncle Tom’s Cabin had galvanized pre-war America, the heartwarming nostalgia of Rip now had a healing effect. By 1869, only three years after his return from England, Joe was said to be worth half a million dollars.

He was also remarried. Sarah Isabel Warren was a second cousin, the well-bred daughter of a thriving Chicago family connected to the theater, though never an actress. He was thirty-eight, she was seventeen (a little younger than Charley), and their apparently happy marriage lasted until Joe’s death, giving Joe four more children. His personal reputation had always been spotless—he was by nature clean-living—but he also was responding to Victorian America’s expectations for a family entertainer, never, for instance, allowing himself to be seen drinking in public. (In private it was a different story.)

The one aberrational episode in his life remained hidden from everyone except Sarah. In 1889 he received a letter postmarked Melbourne, in which a twenty-six-year-old named Joseph Sefton wrote that he had just learned from his dying grandmother that he had been born of a liaison back in the 1860s between the new widower, Joe, and a young soubrette employed in Joe’s Australian company. The facts were irrefutable, and the letter was modest, deferential, and undemanding:

If I am misinformed in this matter pray dismiss from your mind any thought of me…. Whatever your reply is, Yea or Nay, it will be accepted by me as a final disposition of the matter.

It was five months before Joe replied (could he have been consulting private detectives in Australia?), but when he did, his response was forthright and welcoming:

My Dear Son, all that your grandmother has told you is true…. If the world connects any shame with such matters, and it usually does, the blot should fall upon me rather than on you.

As to whether the young man should reveal the relationship, Joe replied:

You are a man and have a right to act as you please…. I place the matter unreservedly in your own hands…. When we meet…you will find that neither me or mine will receive you with anything but affection.

They never did meet, and young Joseph chose to keep the facts of his paternity to himself, but father and son corresponded until Joe’s death, Joe sending his son money through the years and remembering him in his will. (He did, however, instruct Joseph to write to him at the Players Club, not at home.)

Joe’s nontheatrical pursuits were lifelong, passionate, and respectable. Most important to him, from childhood, was painting. Wherever he was, whenever he had a moment, he was at his easel, turning out scores of unpopulated landscapes derivative of Corot and the other Barbizon artists, but well above the level of the average amateur. (When his great friend William Winter—who happened to be America’s most influential theater critic—was preparing to write Joe’s biography, he asked, “What would you do if you couldn’t paint?” Joe replied in all seriousness, “Die, I think.”)

His passion for fishing was equally strong, alone or with a carefully chosen companion—one of his sons, or a close friend like Grover Cleveland. His homes were bought or built in relation to their proximity to water. And in fact, his third almost compulsive private occupation was acquiring real estate—not as an investment, although he was extremely shrewd about anything involving money, but as if to reassure himself of his prosperity. He first bought estates in Yonkers, New York, and Hohokus, New Jersey; then an extensive plantation in the bayous of Louisiana (which he turned into a paying proposition); then a substantial house in Buzzard’s Bay, Massachusetts (along with 156 acres), which when it burned down he replaced with an even grander one; and eventually a large spread in Palm Beach. Careful to maintain his homespun image, he lived, as Bloom puts it, “in the midst of romantic rusticity, but he lived in baronial splendor.”

Everything was for the family—they were never going to suffer as he had suffered. He dotted the various properties he owned with houses for the children and their own families, with happy get-togethers of food, games, and family theatricals. His homes, Benjamin McArthur remarks, “were essentially great, sprawling playhouses.” Charley, and then others of his sons, managed his affairs. And, it was noticed, his generosity to his family was exclusive: Joe Jefferson gave no money to causes.

He was, however, central to a famous moment in theater history. In 1870, a much-loved old actor named George Holland died in New York, and Joe accompanied one of his sons to the church where Holland had worshiped and where his family wanted the funeral held. The Reverend Lorenzo Sabine, however, would not countenance burying an actor from his church. Joe, far from being a churchgoing religious man, was indignant, but he restrained himself and asked: “Well, sir…is there no other church to which you can direct me, from which my friend can be buried?” and was told that “there was a little church around the corner” where he might get it done. “Then,” Joe replied, “if this be so, God bless ‘the little church around the corner.'” The ensuing public outrage (Mark Twain called Sabine “a crawling, slimy, sanctimonious, self-righteous reptile”) turned the Little Church into a shrine for the profession, helped promote the respectability of actors, and further burnished Joe’s reputation.

The most obvious result of Joe’s anxiety about money was his refusal, or inability, to stop performing; he was still touring in his seventies and still raking in immense fees. Critics complained about the rickety quality of his productions—this was another area in which he chose not to spend money—as well as the staleness of his repertory, but audiences kept coming, even when, as we can see from Hurstwood’s remarks in 1890, they acknowledged the staleness.

His repertory, however, was not as totally restricted as people assumed it was: he always kept his early successes in readiness, and eventually he parlayed one of his oldest characterizations, Bob Acres, into a triumphant alternative to Rip, radically reshaping The Rivals to center on Bob, and as usual humanizing an essentially farcical character by making him more sympathetic. Critics complained at this distortion of the text, but as he well knew, the audience came to see Joseph Jefferson, not Richard Sheridan; he toured his Bob for over three years. It was only in the year before his death—having performed Rip well over five thousand times and, it was estimated, being worth more than five million dollars—that he retired from the stage to the benign climate (and boom real estate market) of Palm Beach.

Of the two recent biographers, Bloom takes the more skeptical view—admiring and even fond, but insistent that Joe’s eye was steadily fixed on the main chance and that his constant self-deprecation and aw-shucks homeyness were partly a construct that masked his great ambition and his determination to charm everyone:

As both child and adult, Jefferson really was lovable, but he also learned to be lovable, how to play lovable, and how being and playing lovable produced substantial rewards.

Bloom’s account places Joe in the direct line of American go-getter success stories, which stretches from Benjamin Franklin through Horatio Alger. He was accomplished, he was genial, he was industrious, but most of all he was compulsively upwardly mobile.

Bloom also sharply questions certain of the legends that Jefferson encouraged—the story, for instance, of how when his family was struggling to get a foothold in Springfield, Illinois, in the 1830s, it was a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln who procured for them the necessary license to perform. Perhaps; but whatever Lincoln did or didn’t do was done for the advance guard of the larger Jefferson tribe, before Joe and his parents arrived in the Midwest. Benjamin McArthur, given to special pleading for his hero, has to acknowledge that here at least Joe fudged or forgot the facts. (His word is “embellished.”)

McArthur’s greatest strength lies in his knowledge of the way the American theater developed during Joe’s lifetime. When he was growing up, for instance, a great star moved around the country with his famous roles, dropping in to perform with established stock companies everywhere, all of which knew and could mount the basic repertory and, with a single rehearsal, put on Macbeth with Edwin Forrest or Richard III with Junius Brutus Booth, father of Edwin and John Wilkes. The touring star was the jewel, the local company was the setting—much the way international opera works today.

What changed things irrevocably was the expansion of the railroad system during and after the Civil War. Now entire companies could form in New York and road-show their wares with cast, costumes, and scenery intact. Between 1873 and 1880, the number of local stock companies plummeted from more than fifty to fewer than eight, centralizing the American theater and, incidentally, altering the way young actors learned their trade.

The conditions under which actors performed changed even more drastically. Joe’s memoirs paint a grim if somewhat romanticized picture of the roughness of the venues—barns, barrooms, even a porkhouse (in Pekin, Illinois)—and the audiences that actors had to contend with during the earlier decades of the century. McArthur gives as an example the story of an intoxicated South Carolina congressman who took offense at an actor’s lines, “pulled out his pistol and fired at the stage….” (The stage manager, in what McArthur refers to as “a classic of understatement,” warned the audience that “if there is to be shooting at the actors on the stage, it will be impossible for the performance to go on.”) This is a far cry from the proprieties and pretensions of late-Victorian theatergoers—Hurstwood and Carrie in their box at a resplendent Chicago theater.

McArthur’s work is occasionally blemished by sociological overthink and eruptions of overwriting. (About the friendship between Joe and Edwin Booth: “Raised in the theatre and now hitched to Thespis’s cart, the two forged a bond. Their simpatico may also have been rooted in a complementarity of temperaments.”) These defects, however, don’t negate his achievement in helping reveal to us our forgotten, and fascinating, theatrical past.

Joe had no faith in his being remembered: “There is nothing so useless as a dead actor.” Despite his acknowledgment of, and gratitude for, his spectacular good fortune, there was a strain of melancholy in him. “I am not an optimist,” he said, “I too often let things sadden me.” And, “The saddest thing in old age is the absence of expectation.” At the age of seventy-six—his health having given way completely, and the touring finally at an end—there was nothing left for him to do but die.

And as he had predicted, he soon slipped out of the national consciousness. The homespun America that Rip (and he) represented was now beyond nostalgia; it was forgotten, except perhaps in the pastoral romances of D.W. Griffith, and they too were quickly outdated by World War I and its aftermath. Loving memoirs of him appeared after his death, and then an occasional appreciation in a magazine. The last public sighting of him I’ve come across is a 1941 Saturday Evening Post ad for Maxwell House coffee. “When the Great Joseph Jefferson Was Feted at the Famous Maxwell House,” runs the headline, above an insipid watercolor of Nashville society feting him.

From the handsomely garbed men and women sipping their coffee in the Maxwell House, to the very gamins in the street, the talk is of nothing but the distinguished Mr. Jefferson and his play.

It would be nice to think that this ad sold some coffee.

Today, all that is left of him, apart from a few scraps of film and a couple of faint recordings, all from the 1890s, are a Joe Jefferson Playhouse in Mobile and Chicago’s annual theater awards called the Jeffersons, or Jeffs—though it’s unlikely that anyone either presenting them or receiving them knows much about the renowned actor for whom they were named. Even so—unexpectedly and unpredictably—a century after his death we have these two excellent new accounts of his life and achievement. No one would have been more surprised than Joe.

This Issue

October 22, 2009