One of the special pleasures in going to museums or looking through the odd survey of a museum’s collection (or a private collection) comes in finding work by artists who are at once almost entirely unknown and stimulating in some way. If, in learning more about these figures, their work grows in fascination, we probably want it to be better known, though at the same time we half-believe it ought to remain a little buried. This isn’t for fear that when seen in full this or that artist won’t measure up but because as somewhat mysterious figures they add a welcome note of uncertainty and incompletion to our sense of the past.

For some of us, the Spanish still-life painter Luis Meléndez (1715–1780) has for years been precisely such a figure. In 1987 the late Michael Levey, writing in The National Gallery Collection, a guide to London’s National Gallery, noted that the artist had only recently begun to attract attention, and it was clear, from looking at the museum’s Still Life with Oranges, Walnuts, and Boxes of Sweets, which Levey reproduced—a clearly lit, casual yet orderly arrangement of foods and kitchen objects done in an array of tans, oranges, and browns and set against a dark background—that Meléndez was adding a distinctive note to Spanish, if not European, painting. Like the work of Chardin, the preeminent still-life painter of the eighteenth century, this 1772 canvas presented an unassuming, even humble, subject, and it went far further than Chardin in dispensing with musty symbolic trappings and any air of sentimentalized warmth.

The London picture (and other Meléndez works one encountered here and there) set off sparks in many directions, however. With his feeling for crisply clear forms placed against empty dark backgrounds, Meléndez appeared to be a lone reviver of a particularly Spanish way of thinking about still life that had briefly been evident some hundred and fifty years earlier. This was when, in the early 1600s, two giants of Spanish art, Velázquez and Zurbarán, made a handful of similarly stark, and extraordinary, still lifes (or paintings that included still-life passages) of everyday foods, jugs, or cups, and when the lesser-known Juan Sánchez Cotán and Juan van der Hamen y León, also presenting isolated and brightly lit foods in radically bare settings, were among the first artists anywhere to concentrate purely on still lifes.

Meléndez’s art looked forward in time, too. The hard, steady light and uncluttered, undainty appearance of his still lifes provided a foretaste of the pictures that Jacques-Louis David would be making in the 1780s and 1790s of the classical world seen as a series of ardent, politicized, dramatically spotlit tableaux. The Spanish artist’s conception of a realm of catty-cornered items placed on a stage that was simultaneously too bright and too dark even made one think of the elegant and moody still lifes of boxes, books, and candles that John F. Peto, working in obscurity in rural New Jersey, would be making around 1900.

The Luis Meléndez retrospective organized by the National Gallery in Washington, which follows retrospectives for the artist in Madrid and Dublin in 2004—and is now at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—is thus an anticipated event. It is not an exhibition that has come out of the blue. Nor is it quite what one had hoped for. Bringing together thirty of the less than one hundred and fifty paintings by Meléndez that have survived, it reveals an emotionally reserved artist, and one who, from the evidence, and whether from commercial needs or the needs of his temperament, kept himself—a little unrelievedly—to the single theme of what we eat and drink and the utensils and paraphernalia used in relation to food. Seeing Meléndez in number, one misses the expansiveness of spirit and sense of majesty with which Zurbarán and Velázquez could look at a cup and saucer or a water jug. A bit of John F. Peto’s playfulness and the literal tenderness of his touch as a painter would help, too.

Meléndez’s tightly focused realism is such that when he paints a raw wood box or a cork cask, that object’s essential texture has been perfectly captured. This is no mean accomplishment. But what he doesn’t do, and Velázquez did in his early days when he painted scenes set in kitchens, is present the very texture of the object and at the same moment a sense of paint and brushwork being beautiful in themselves.

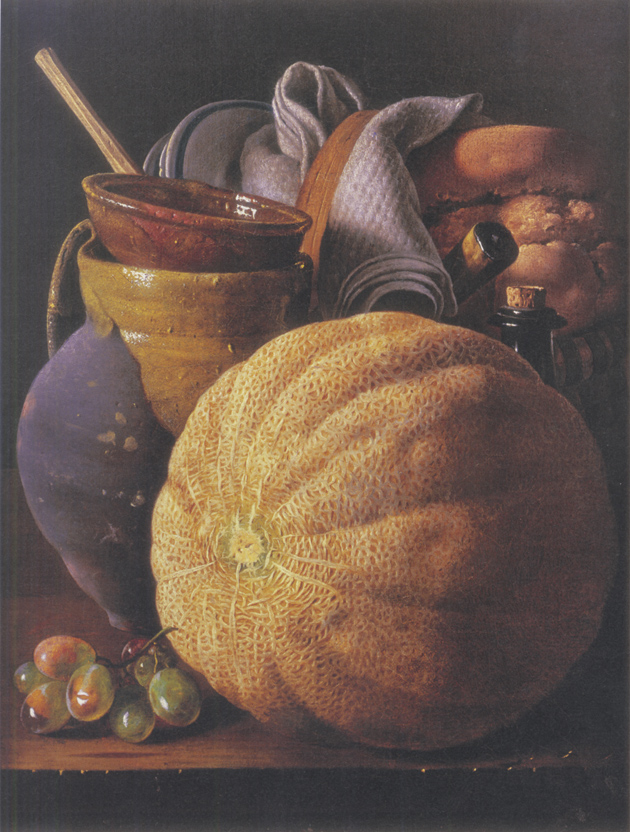

Meléndez’s approach is disconcertingly inconsistent. He turns out to be a tremendous painter of dry, porous, and unreflective items such as raw wood, clay jugs, hard-crusted breads, a melon’s skin. Yet while he can expertly create the gleam of light on a jug, he is mechanical when he has other reflective or wet things to paint such as grapes or open pomegranates or silver; he suddenly resembles an impatient folk artist, stamping every item with the same impersonal sheen. His handful of pictures where many pieces of fruit, some cut open and dripping, are placed in landscape settings, rather like foodstuffs out in the country on their own picnic, have a stereotypical lavishness and feel as if they could be the product of any number of cultures or eras.

Advertisement

Yet Meléndez also had an extraordinary aptitude for finding balances among objects and among subdued earth colors and for relating objects to the space, light, and shadows that envelop them. (His backgrounds are sometimes an unusual and sumptuous dark purple-brown.) And in a number of pictures on display he is an even more powerful artist than the London Still Life with Oranges, Walnuts, and Boxes of Sweets (which is not in the show) suggests. When he worked with vertical formats his point of view was very close to the items he was painting, and, unlike in his more numerous pictures with horizontal formats, where the objects feel like they are on display, he paints only a very few items and crops the image tightly. The result is that his jug or bread can loom forth; and, combined with his lunar light, pictures such as Still Life with Bread, Grapes, Jug, and Receptacles and Still Life with Melon, Jug, and Bread, which date from around 1770, are as disquieting, even as sinister, as they are svelte and superbly balanced.

Meléndez’s vertical-format pictures almost always measure some eighteen or nineteen inches high by a foot or so wide. They aren’t big, in other words. But given that they are always about the balanced relationship of objects seen in a tightly defined space, and that some of those objects, relative to the whole space, can be quite big, the pictures, particularly when seen in reproduction, can appear disorientingly huge—as does the cantaloupe, for example, in Still Life with Melon, Jug, and Bread.

Meléndez wasn’t the first still-life painter, of course, to look at his subject close up. Flemish painters of flowers in the 1600s might make pictures where a floral arrangement comprised of countless specimens comes bursting out at a viewer. But in Still Life with Melon, Jug, and Bread, there is nothing joyfully overabundant about Meléndez’s cantaloupe. It possesses, rather, an almost intimidating immensity. Meléndez’s upright pictures are different in their formal impact than any still lifes that I can think of that precede them in time. The surrounding space in, say, Still Life with Bread, Grapes, Jug, and Receptacles feels calibrated to a hairbreadth. The relation of the elements in the picture to each other and to the dark space they are part of gives the work a physical sense of tension that is rare in still-life painting from any era.

The mood Meléndez captures is also subtly unlike that in most still-life painting before him. In his strongest and seemingly most personal pictures, we don’t look at the aftereffects of an event (like the remnants of a meal or, as in Chardin, a rabbit’s having just been killed). Nor do the assembled objects exactly suggest, as so many still-life painters have suggested, ripeness in itself. Yet his art is certainly about appetite of a sort.

Just to list the items Meléndez paints is to become hungry. In addition to fruit and jugs and nuts and loaves, we see wine bottles partially emerging from coolers made of cork, wedges of cheese sitting atop the paper packages they come in, and bream and pigeons placed alongside the tomatoes and garlic and pots that they will be cooked with or in. There are packets of seasonings, chunks of ham, and his wood boxes contain (as we learn in the catalog) jellied fruit, nougat, or marzipan. There are honey pots, slabs of chocolate, and narrow-necked copper vessels for making chocolate drinks. It is an inventory that conjures up the overlapping realms of eating, kitchen life, and domesticity. Yet what one takes away from this art is not tastiness or culinary history so much as some novel combination of anticipation, readiness, and entrapment.

His jugs and pots, for example, are often lidded, and his loaves of bread sometimes show the stuffing they have been filled with poking out. His wood boxes, on which he sometimes painted the initials LM and which suggest little coffins, are mostly seen as shut but they can be slightly wedged open, with a hint of a paper package emerging. These bits don’t ask to be interpreted symbolically. When we see the neck of a wine bottle sticking out from a cork cask, we understand that this was simply what might be found in a Spanish home at the time. But it also adds a related note to the artist’s particular underlying drama, where peeking forth and being sealed up—or aspiration and confinement—are hard to tell apart.

Advertisement

Looking at Meléndez’s still lifes as works presenting an ambiguous message—and as being more than an art of virtuoso realism—certainly makes sense in relation to the details of his life. Working from the surviving documents, Peter Cherry, the principal author of the show’s catalog (and an authority on Spanish painting who wrote for the catalogs of the Meléndez retrospectives in Dublin and Madrid), tells a story of repeated instances of intemperateness, rejection, and reinvention. We read about a proud and hot-tempered man who was stymied time and again and yet kept finding ways to keep his spirits and career afloat. Actually, we read about two hotheads. Luis’s father, Francisco Antonio Meléndez, who was also a painter (as were Luis’s brother and one of his sisters), set the pace in the family for arrogance and a propensity for wounded pride. It hardly went well with him that, publicly proposing to Philip V in 1726 that Madrid have a royal academy and offering himself as its head, he was passed over for the position when the academy eventually came into being.

In subsequent incidents with his colleagues at the academy, Francisco Antonio’s sense of his standing was so insulted and his retaliations were so fierce that he was expelled from the institution. Luis, meanwhile, went from being one of the first students to enroll in the academy and soon its top-ranking student to failing to win a scholarship to study in Rome. The day his father was expelled found Luis embroiled in an argument over a drawing and then, because of his temper, expelled (from the life drawing class) as well. The social standing of the entire Meléndez family was further muddled by an incident stemming from Luis’s sister Clara’s having been raped. The culprit, a student of Francisco Antonio’s, was banished from Madrid. Foolishly returning to the city four years later, he was slashed in an attack carried out in public—an assertion of Meléndez family honor that resulted in Francisco Antonio and Luis both being arrested and that Peter Cherry, looking at the evidence, says was surely carried out by Luis.

The heedless but wily Francisco Antonio kept finding jobs for himself and for his artist children for years. But Luis on his own was always running into obstacles. His expulsion from the academy meant he could never earn a living from teaching, and patronage would thereafter always prove difficult. Like his siblings, he was versed in his father’s trade as a miniaturist, and spent years decorating choir books for the Royal Chapel. Then he turned his energies to still-life painting, a terrain still considered fit only for artists of little ambition and one that, in Spain in the 1760s and 1770s, he had all to himself.

His abilities as a miniaturist and still-life painter, however, didn’t help him when, between 1759 and 1774, he petitioned Charles III four times for an appointment as court painter. He was rejected each time. Eventually, the King’s son, the Prince of Asturias, paid him for a large suite of still-life pictures; but as the examples in the exhibition indicate, the increasingly noisy and festive still lifes he made to fill the prince’s commission took him further and further from his gift for subtle and taut compositions.

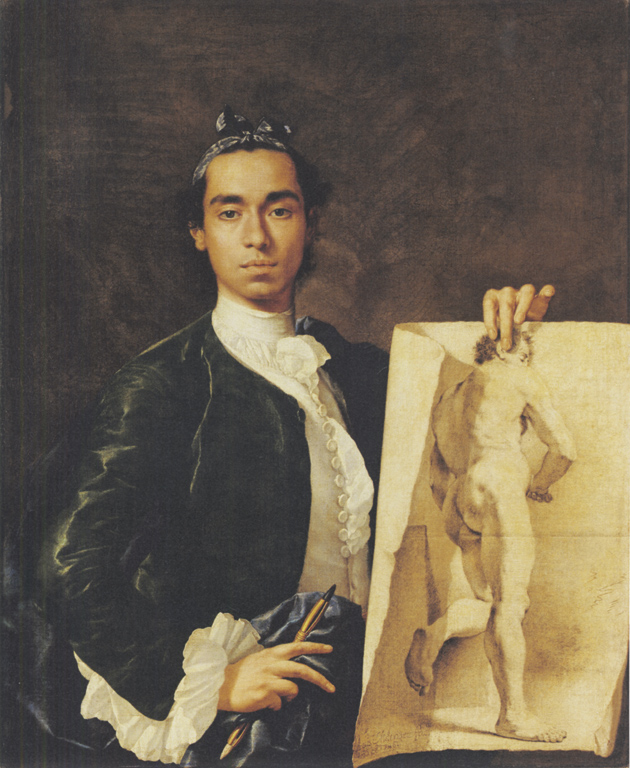

Cherry lucidly lays out his subject’s biography yet he never suggests that Luis Meléndez’s pictures mirror the complexities of his life. Cherry and the other authors of the catalog leave a reader feeling that Meléndez’s art isn’t really about much of anything. But in a way they don’t have to spell out the elements of concealment and two-sidedness in the painter’s best work —the biographical details almost aren’t needed, either—because Meléndez himself planted enough of a clue. It comes in the form of a self-portrait dated 1746, done when he was thirty-one and the young lion of Madrid’s art scene. This arresting picture (in the Louvre’s collection and, fortunately, part of the current show) is apparently the only oil painting of his to have come down to us that is not a still life. It presents an undemonstratively self- possessed and handsome, even beautiful, young man, his hair tied with a ribbon, in the fashion of the day. He has a charcoal holder in one hand, and displays, with the other, a large drawing of a male nude that is undoubtedly his own work.

Self-Portrait embodies the essence of every confident young artist exhibiting his ticket to fame. It is barely necessary to be told that this young artist expects he will be a great figure painter, the goal of goals of the art of his era. And what he went on to accomplish, in a spectacular detour, was a body of still lifes. The regal self-image and the still lifes that follow together provide a novel’s worth of information. We feel they bear witness to a conflict that wasn’t, or was, worked out—and of goals that weren’t, and yet were, met. We think we know, moreover, why that cantaloupe in Still Life with Melon, Jug, and Bread is quite possibly the most imposing piece of fruit in the history of art.

This Issue

November 5, 2009