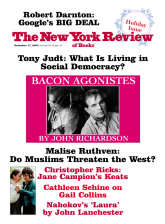

To celebrate Francis Bacon’s centenary in 2009, Tate Britain mounted a retrospective exhibition that was subsequently shown at the Prado in Madrid and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Bacon’s theater of cruelty was an enormous popular success at all of its venues, but especially in New York, where he was hailed by fans as the greatest painter of the twentieth century. However, such clouds of hyperbole were already a touch toxic following the sale in 2008 of a flashy triptych for $86 million, and serious reviews of the Met show were anything but favorable. Also, those of us who care about the integrity of an artist’s work were worried by the appearance on the market of paintings that, if indeed they are entirely by him, Bacon would never have allowed out of the studio.

As a longtime fan of Bacon, I have strong feelings about these matters. My admiration dates back to World War II, when, like many another art student, I was captivated by an illustration of a 1933 painting entitled Crucifixion in a popular book called Art Now, by Britain’s token modernist, Herbert Read (first published in 1933, and frequently reprinted). Read’s text was dim and theoretical, but his ragbag of black-and-white illustrations—by the giants of modernism, as well as the chauvinistic author’s pets—was the only corpus of plates then available. This Crucifixion—a cruciform gush of sperm against a night sky, prescient of searchlights in the blitz—was irresistibly eye-catching. But who Bacon was, nobody seemed to know.

And then (circa 1946), craning my neck to get a look at a large canvas carried by a youngish man with dyed hair on the doorsteps of a neighbor’s house, I realized that this had to be the mysterious Bacon. The neighbor turned out to be the artist’s cousin and patron. I arranged for a mutual friend to take me to see him. Bacon struck me as being exhilaratingly funny—very camp in his disdain for masculine pronouns. Everything about his vast, vaulted studio was over the top: martinis served in huge Waterford tumblers; a paint-stained garter belt kicked under a sofa. The place had famously belonged to the pre-Raphaelite Sir John Everett Millais, but a later owner had left more of a mark on it: Emil Otto Hoppé, the foremost “court” photographer of his time. Hoppé’s grungy hangings had survived the blitz, and so had the great dais where, crouched under a black, umbrella-like cloth (a feature of Bacon’s earlier paintings), he had photographed society beauties in aigrettes and pearls. The ramshackle theatricality that permeated the studio also permeated the three iconic mastershockers—scrotum-bellied humanoids screaming out at us from the base of a crucifixion—that were about to make the artist famous.

Francis’s blind old nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, knitting away at the back of the studio, came as a surprise. Besides helping Francis cook—she slept on the kitchen table—Nanny provided cover for Francis’s shoplifting sprees (groceries, cosmetics, and Kiwi shoe polish for his hair). Nanny also helped him organize the illicit roulette parties that paid for the copious drink and excellent food he served to his guests. The lavish tips she extorted from gamblers desperate to use the one and only lavatory helped pay off Francis’s gambling debts. Supposedly she also vetted his lovers. When she died in 1951, he took against the studio and sold it—a move he would always regret. The space would linger on in his visual memory: many a triptych is set in a photographer’s studio in Hell.

Ultrasecretive about his artistic provenance, Bacon was exhibitionistically frank about the traumatic adolescent events that would define his role as an artist as well as a lover. In the recently published revised edition of his excellent, refreshingly unhagiological biography, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma,1 Michael Peppiatt describes a fancy dress party given by Francis’s parents—the chilly, moneyed mother and the brutal, bluish-blooded father—at Cannycourt, near Dublin, where Captain Eddy Bacon trained racehorses that, according to Francis, very seldom won. Already adept at seducing his father’s grooms, sixteen-year-old Francis had gotten himself up as

an Eton-cropped flapper, complete with backless dress, beads, and a cigarette holder so long it reached to the candles in the middle of the table. Dressed as a curate, his father stared uneasily and said nothing as Francis rolled his eyes [and] shook his earrings.

Unease turned to rage when Captain Eddy caught his son wearing his mother’s underclothes and gave him a thrashing. As a result “I fell sexually in love with him,” Francis said. Years later, he would still slip on his fishnets in the hope of a replay.

To “make a man” of Francis, his father turned him over to a supposedly—though not in the least—respectable cousin for a disciplinary two months in Berlin. To Bacon’s delight, the cousin turned out to be bisexual and, he assured me, “one of the most vicious men I ever met.” Two months in the German capital, at its most depraved, reinforced the boy’s masochistic and fetishistic proclivities. Berlin did indeed make a man of Francis: “Tough as old boots, albeit camp as a row of tents,” an old friend recalled. However, his next stop, Paris—he spent two months nearby at Chantilly—would make an artist of him. His visit coincided with an exhibition of Picasso’s drawings at Paul Rosenberg’s gallery. Ironically, the drawings were mostly classicistic ones set in an ancient Mediterranean world. Bacon would later condemn these works, but at the age of seventeen he was captivated. Picasso would be the only contemporary artist whose influence he would ever acknowledge.

Advertisement

Francis seldom mentioned it, but he was proud of being a collateral descendant of Elizabeth I’s all-powerful chancellor, after whom he had been named. He was especially intrigued that this Renaissance genius—philosopher, cabalist, courtier, Rosicrucian, statesman, as well as a writer so sublime that he is sometimes credited with writing Shakespeare’s plays—had been a flamboyant homosexual. Lytton Strachey had made much of this in his book Elizabeth and Essex, published to wide acclaim in 1928. Strachey’s baroque characterization of his forebear had fascinated him, Francis told me. How could he not identify with Strachey’s view of the Elizabethan Bacon?

Instinctively and profoundly an artist…one of the supreme masters of the written word. Yet his artistry was of a very special kind…. His eye—a delicate, lively hazel eye—“it was like the eye of a viper,” said William Harvey—required the perpetual refreshment of beautiful things.

Francis would also have sympathized with his forebear’s “exuberant temperament [that] demanded the solace of material delights,” expensive boyfriends, “half servants and half companions,” whom he had shod in Spanish leather boots, since “the smell of ordinary leather was torture to him.” The twentieth-century Bacon would ironically mock the family’s motto, Mediocria firma (“moderation is best”), inscribed on the armorial dinner plates he would inherit. His illustrious ancestry and his sense of it might also account for his personal largesse as well as his desperate attempts at grandiloquence, which undermine many of the later triptychs.

Bacon’s earliest paintings were mostly pastiches of Picasso; though attractive, they failed to sell. Since this driven, as yet unformed artist had no desire to be perceived as a pasticheur, he destroyed most of them. He continued sporadically to paint and decorate, but devoted most of his energies to gambling. Successive stays at Monte Carlo—hence the glimpses of Mediterranean vegetation in the early works—financed by a lover, enabled him to become an expert roulette player as well as a canny croupier in private games. He would approach painting in much the same way as he approached gambling, risking everything on a single brushstroke.

Never having attended an art school was a source of pride to Bacon. With the help of a meretricious Australian painter, Roy de Maistre, he taught himself to paint, for which he turned out to have a great flair; tragically, he failed to teach himself to draw. Painting after painting would be marred by his inability to articulate a figure or its space. Peppiatt recalls that, decades later, so embarrassed was Bacon at being asked by a Parisian restaurateur to do a drawing in his livre d’or that he doubled the tip and made for the exit.

After Bacon’s death, David Sylvester, the artist’s Boswell-cum-Saatchi, attempted to turn this deficiency into an advantage. In a chapter of his posthumous miscellany, entitled “Bacon’s Secret Vice,” he proposed an “alternative view” of this fatal flaw: “His most articulate and helpful ‘sketches’ took the form of the written word.”2 The “precisely worded” examples that supposedly demonstrate the linguistic origin of Bacon’s paintings turn out to be a preposterous joke: offhand notes scrawled on the endpapers of a book about monkeys: “Figure upside down on sofa”; “Two figures on sofa making love”; “Acrobat on platform in middle of room”; and so on. Sylvester’s contention that this shopping list constitutes “Bacon’s most articulate and helpful sketches” raises doubt about the rest of his sales pitch.3

Bacon’s own excuse for his graphic ineptitude is more to the point: “[The painter] will only catch the mystery of reality if [he] doesn’t know how to do it”4 is what he actually told Sylvester. This is fine, but only so long as the artist avoids subjects that call for graphic skill, subjects, for instance, that include hands. His celebrated variants on Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X are either magnificent flukes or near-total disasters. In the earliest of this ten-year series, Bacon famously portrays the Pope screaming. He’s good at screams but hopeless at hands, so he amputates, conceals, or otherwise fudges them. At the age of eighty, Bacon apologized for this series to Michael Kimmelman: “Actually, I hate those popes because I think the Velázquez is such a superb image that it was silly of me to use it.”

Advertisement

Infinitely more effective are the versions that Bacon did around the same time of Eadweard Muybridge’s celebrated sequential photographs in The Human Figure in Motion, which record successive stages of various physical activities. Muybridge’s photographs enormously facilitated Bacon’s drawing, literally squaring up the composition for him to transfer to canvas. The finest of them, Two Figures, is based on pictographs of two athletes wrestling each other to the ground. Known with some justice to Bacon’s friends as The Buggers, this work is the more subtle and hauntingly sexual for overtly depicting something supposedly innocent.

Inability to draw might explain Bacon’s initial decision to become a decorator. He had a real flair for interior design. His furniture was chic but brutal—too much for potential clients, and so he became a painter, and hustled on the side to pay the bills. Calling himself Francis Lightfoot (after his nanny), he advertised in the personal column of the London Times. An elderly client accused him of theft. “Probably true,” he admitted later. Unluckily, the client was a relative of the vengeful Douglas Cooper, who had bought a major piece of Bacon’s furniture and arranged for the publication of his Crucifixion in Art Now. Later, Cooper would bad-mouth Bacon in favor of his rival, Graham Sutherland, to the former’s delight and gain.

Bacon’s passion for belle peinture and his inventive handling of paint would usually but not always compensate for his inept draftsmanship. Though painterliness was a quality disdained by most modernists, Bacon realized this was the element that would enable him to tweak the onlooker’s senses into accepting and indeed enjoying a painful visual shock. To enhance his paint surfaces he tried out additives—pastel and tempera—but in the end stuck to oil paint, which he manipulated with ever more gestural abandon. On an early visit to the studio, I watched Francis experiment. Ensconced in front of a mirror, he rehearsed on his own face the brushstrokes that he envisaged making on canvas. With a flourish of his wrist, he would apply great swoops of Max Factor “pancake” makeup in a gamut of flesh colors to the stubble on his chin.

The makeup adhered to the stubble much as the paint would adhere to the unprimed verso of the canvas that he used in preference to the smooth, white-primed recto. I told him that this effect evoked Rupert Brooke’s line about “the rough male kiss of blankets.” Besides setting his faces and figures spinning, gestural twists endow his portrait heads—to my mind far and away his most powerful and original works—with a dose of his own inner turmoil.

Bacon’s attempts at a conventional likeness usually fail, but when he connects with what he calls “the pulsations of a person,” he usually triumphs, particularly when that person is himself. Instead of working from a sitter, he would have his gay drinking companion, John Deakin, take nude photographs of the women he proposed to paint. Deakin, who on the side would sell the photographs to sailors for ten shillings each, enjoyed mortifying his “victims,” as he called them. Bacon’s favorites were Henrietta Moraes, a drunken Soho groupie who worshiped Bacon and his circle; Isabel Rawsthorne, a desperate allumeuse who had had affairs with Picasso, Derain, and above all Giacometti; and Muriel Belcher, the formidable foul-mouthed fag-hag of the Colony Room. These were women Bacon could empathize with. To that extent their portraits are self-portraits, as are the superb ones of his victim-to-be, George Dyer. Significantly, there is not a trace of self-identification in the twenty or so portraits of Lucian Freud. There was no question of victimizing him.

In 1950, Bacon’s studio would become the focus of attention for a three-day celebration that, in retrospect, was the coming-out party for a new variety of bohemia. In its excess it could also be seen as Bacon’s debut as a star. The occasion was the wedding of his close friend Ann Dunn, penniless daughter of a steel magnate, and Michael Wishart, son of the Communist Party’s publisher. Both were painters, Dunn an exceedingly sensitive one. Two hundred guests were invited; two hundred more gate-crashed.

It was a totally new mix. Although the guests were mostly heterosexual, the ambience was decidedly gay. Francis had painted the chandeliers red to match his maquillage; at the piano an old queen belted out campy versions of popular songs. Same-sex couples embracing in dark corners were not necessarily the same color. A woman known as “Sod” (real name Edomy) Johnson, who lived on the top of a bus, helped to welcome the guests: these included members of Parliament and fellows of All Souls, as well as “rough trade,” slutty debutantes, cross-dressers, and the notoriously evil Kray brothers (gay gangsters Francis was proud of knowing). The bridegroom was a junkie, as were such guests as Sir Napoleon Dean Paul and his beautiful sister, who were both on the Home Office list and thus entitled to an official drug ration.

The consumption of hundreds of cases of champagne would have left Francis, who was as generous as he was extravagant, broke, had he not had the support of a rich and indulgent lover, a merchant banker called Eric Hall. Hall had ditched his wife and family to become a stand-in for the flagellant father Bacon desired and hated. After eight years, this relationship came to an end. A devotee of Proust, Bacon may have identified too closely with that writer’s Baron de Charlus, who, in a memorable scene, complained to his pimp that the brute procured for him was insufficiently brutal.

Hall’s replacement was a demonic lover out of the pages of another of Bacon’s favorite writers, Georges Bataille. A former fighter pilot, Peter Lacy was a dashing thirty-year-old whom I remember playing Gershwin and Cole Porter on a white piano in a bar called the Music Box. He owned an infamous cottage in the Thames valley, where Francis would spend much of his time—often, according to him, in bondage. Alcohol was a major link between the two men. Unfortunately, drink released a fiendish, sadistic streak in Lacy that bordered on the psychopathic. Besides taking his rage out on Bacon, he took it out on his canvases. To his credit, however, he inspired some of his lover’s most memorable works, among them, the Man in Blue paintings: a menacing, dark-suited Lacy set off against vertical draperies inspired by Emil Hoppé’s, and some black rubber curtains Bacon had used as a decorator.

A 1955 self-portrait with a bandaged head seemingly refers to Lacy’s most heinous assault. In a state of alcoholic dementia, he hurled Bacon through a plate glass window. His face was so damaged that his right eye had to be sewn back into place. Bacon loved Lacy even more. For weeks he would not forgive Lucian Freud for remonstrating with his torturer. Mercifully, Lacy moved to Tangier, where he played the piano in Dean’s famously raffish bar. Bacon would occasionally join him. He enjoyed Tangier’s expatriate intelligentsia: Paul and Jane Bowles; Allen Ginsberg, who tried and failed to get him to paint his portrait; William Burroughs, whom he admired and stayed friends with; and the playwright Joe Orton, soon to be done in by his murderous boyfriend. He also enjoyed the torturers in the local brothels. Tangier finished Lacy off. “He was killing himself with drink,” Bacon told Peppiatt, “like a suicide, and I think in the end his pancreas simply exploded…. He was the only man I ever loved.” The artist’s memorable Landscape near Malabata, Tangier depicts Lacy’s place of burial: a threatening patch of ground with a dark humanoid serpent squirming out of it.

On May 22, 1962, when Bacon was fifty-two, his first retrospective opened at the Tate Gallery to an avalanche of praise never as yet accorded to a modern British artist. A triumph, it was also a tragedy: the day before, death had done away with Lacy, his principal source of sensation—mental and physical, but above all pictorial. Some of his friends saw this as retribution, others as a new dawn for British art. Sylvester was quick to grab Bacon’s coattails. In the years to come he would help him transform himself into a superstar. Today Bacon has come to be seen in the blogosphere as a kind of Michael Jackson of art—an anomalous weirdo of divine power.

Those of us who had hoped that the organizers of the recent retrospective and contributors to the catalog would help us to reevaluate this superstar were in for a disappointment. The badly needed deconstruction of the self-congratulatory interviews between Bacon and Sylvester was not forthcoming. True, in her essay “Real Imagination Is Technical Imagination,” Victoria Walsh acknowledges “just how radical their reformatting and editing had been.” In support of this she cites Sylvester’s preface to the interviews. However, no contributor takes this matter any further. Nor was there any attempt to see Bacon in his rightful historical setting: as one of a trio of brilliant young British artists—Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach being the other two—who felt that abstraction was done for and were out to explore new ways of reconciling paint and representationalism.

In an essay coyly entitled “Comparative Strangers,” Simon Ofield sees Bacon with respect to Keith Vaughn, a highly esteemed figurative painter, yet one far too artistically correct for Bacon’s taste, on the grounds that they were both openly gay men in the 1950s. Because the two artists apparently perused “physique magazines” and happened to be working at a time when the Wolfenden Report—the document that led to the decriminalization of homosexual acts between consenting adults—was about to change Britain’s social and sexual landscape, Ofield concludes that “the paintings of Francis Bacon and Keith Vaughn make sense in pretty close proximity to one another.” Actually, Bacon, who was not entirely immune to the allure of Nazi kink, had little sympathy for gay rights—too politically correct. As for gay artists, the only ones Bacon had a kind word for were Michelangelo, Andy Warhol, and the pornographer known as Tom of Finland. About the Wolfenden Report, I remember Francis echoing his nanny: “They should bring back hanging for buggery.” He was certainly not the only gay Englishman for whom guilt was intrinsic to sex.

Compared to Lacy, Bacon’s next great love, George Dyer, was more victim than victimizer, a good-looking thirtyish petty thief from London’s East End who appeared to be a great deal sharper than he actually was. Cockney sweetness and a slight speech impediment (“fink” for “think”) endeared him to Bacon’s friends. Although an alcoholic like Lacy, George was not a sadist. That would now become Bacon’s role. In the course of an evening, his high-camp wit would sour into incoherent malice. Lucian Freud remembers driving a drunken Bacon home and being kept out of the studio because it was full of “victims of my tongue.” Bacon would goad George into a state of psychic meltdown and then, in the early hours of the morning—his favorite time to work—he would exorcise his guilt and rage and remorse in images of Dyer aimed, as he said, at the nervous system. Such images, a woman admirer of Bacon told me, induced “a visceral shudder” in her.

The dynamics of Bacon’s relationship with George were much in evidence in November 1968, when they arrived for the first time in New York to attend a show at the Marlborough- Gerson Gallery. The visit began pleasantly enough with a gallery lunch. Francis was seated next to a handsome young dealer. Averse as usual to the masculine pronoun, he hissed across the table, “Who’s the gorgeous girl they’ve put next to me?” “Jackson Pollock’s nephew,” I hissed back. “You mean the niece of that old lace-maker?” he said, raising his voice. Egged on by the deafening silence, Francis proceeded to dismiss another prominent American artist as “a neat little sewer,” and yet another as “what’s-his-name who does women.”

That evening, some friends and I took Francis and George out on the town. No equivalent of London’s raffish Colony Room was to be found in Manhattan, so we ended up at a friendly, multiracial, multisexual bar around 100th Street. Childishly eager to play the host, George tried to buy us drinks. Francis wouldn’t have it. “Don’t listen to her. She’s penniless,” and he called imperiously for a magnum of champagne, whereupon the bartender suggested we go elsewhere. George stumbled off and the evening soon ended. Around 3 AM, Francis called me. “She’s committed suicide!” He had found George on the floor of their room at the Algonquin, pockets stuffed with hundred-dollar bills, unconscious from having washed down a handful of his sleeping pills with a bottle of scotch. Vomiting saved him. The gallery had the two of them flown back to England first thing that morning.

Two years later, in a pitiful attempt to strike back, George concealed some marijuana in Bacon’s studio and denounced him to the police. Since the artist was asthmatic and virtually never smoked, a jury found him innocent. Instead of ridding himself of George, Bacon took him back, thereby sealing his fate. The goading worsened, the imagery intensified, and there was a further suicide attempt in Greece.

Once again, a major retrospective would coincide with death. The day of Bacon’s greatest triumph—the opening of his exhibition at the Grand Palais, Paris on October 25, 1971, the show that would bring him the international recognition he craved—George succeeded in his third attempt at suicide. As before, he chose to do so in a hotel bedroom in a foreign land and, as Bacon would paint it, on a toilet seat. After the hotel manager telephoned him at the Grand Palais, the dazed artist took President Georges Pompidou around his show and later attended a dinner for several hundred people organized by his distinguished admirer Michel Leiris. “Death can be life-enhancing,” he later commented, and for the next few years would apply this thought to his last great bursts of heartfelt work, in which Dyer often figures.

The hosannas unleashed by the Paris retrospective climaxed in a Conaissance des Arts magazine poll that crowned Bacon the world’s greatest living artist—ahead of Picasso and the members of the schools of Paris and New York. Whether or not he actually believed this claptrap, Bacon was vain enough and insecure enough to derive an enormous boost from the stardom and the huge hike in his prices. Always more Francophile than Anglophile in matters of art, he was elated by the esteem of the French public as well as the intelligentsia, so elated that he rented an apartment in the Marais where he would spend much of the 1970s.

Michel Leiris would be central to Bacon’s life in Paris. This great writer, ethnographer, and hero of the Surrealist wars was the only littérateur left whose judgment Picasso could trust and, to that extent, a rather more prestigious mentor than Sylvester and the boozy habitués of the Colony Room. Although Bacon had no time for Leiris’s communism, masochism and a gay streak constituted a link. Whether Leiris told Bacon that back in the 1920s he had asked a horrified Juan Gris to take a knife and carve a parting for his hair into his scalp we do not know. What we do know is that Bacon was very conscious of the fact that by virtue of being D.H. Kahnweiler’s stepdaughter, Leiris’s long-suffering wife Zette was dealer to Picasso, who was soon to die. Despite the Conaissance des Arts poll, there would be no question of Bacon stepping into the great man’s shoes.

Now that Paris had crowned him king, Bacon’s work developed a slight French accent. Freud, whose close friendship with Bacon had worn a bit thin, was amused at his new-found fondness for the concept of “accident,” the idea that uncontrolled effects would change the character of a painting. Freud likened “accident” to a horse in Bacon’s stable. “When necessary, Francis has ‘Accident’ saddled and takes him out for a canter.” To judge by many of the paintings in the retrospective, there was another horse in Bacon’s stable, its name “Contrivance.”

“Accident” takes the form of semen-like white paint that Bacon claimed to “fling” out of the tube at some of his canvases. As for the small red arrows he added to his paintings, intended to draw one’s attention to extraneous details, they strike me as little shrieks for help; likewise, the gimmicky bits of trompe l’oeil newspaper that fail to animate the inert foreground areas of his triptychs. Contrivance also takes the form of shadows that fail to generate light or space. They either look cartoonish (for instance, the Batman shadow exuded by the dying Dyer in the May–June 1973 triptych) or as if someone has spilled something.

Three years would pass before Bacon found a successor to George Dyer. The muscular young East Ender John Edwards was less damaged than his predecessor, and therefore less of a tragic muse. He never learned to read, but was very good at figures. Although homosexual, Edwards preferred adolescents, and his relationship with Bacon was all the less fraught for being platonic, seemingly free of sadomasochistic overtones. This may explain why Bacon’s work lost its sting and failed to thrill. Paintings inspired by Edwards as well as a Formula 1 driver and a famous cricketer the artist fancied (fetishism survives in the batting pads) reveal that in old age Bacon managed to banish his demons and move on to beefcake. His headless hunks of erectile tissue buffed to perfection have an angst-free, soft-porn glow. It comes as a surprise to find that MoMA acquired a major example of these campy subjects to replace the superb early Dog painting they had deaccessioned.

By the late 1970s, as the Met retrospective made very clear, Bacon’s work was becoming glib, trite, and color- coordinated to a decorous degree. From boasting that he couldn’t do it—that was the whole point—he let it be known that he could do it, indeed had always been able to do it. Freud believes that Bacon had also lost “the most precious thing a painter has: his memory,” and forgotten that he had done it all better before. The elegance of the Met’s installation, which worked so well in the earlier galleries, worked to the artist’s disadvantage at the end. Few of the later triptychs pack as much of a punch as the explosive Jet of Water and Blood on Pavement (both 1988), which are refreshingly free of the artist’s formulaic figures. As if to register the extent of Bacon’s decline, the Met enabled us to contrast the artist’s wonderful 1944 breakthrough, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, in an earlier gallery with the garish, red carpet remake of it from 1988, which brought the show to a disheartening end.

This year the hundredth anniversary of Bacon’s birth dovetails with the four-hundredth anniversary of Caravaggio’s death next year, and the director of the Galleria Borghese in Rome is celebrating this double event by setting these two artists, who had both been canonized in recent years by gay filmmakers (Derek Jarman, Caravaggio ; John Maybury, Love Is the Devil), against each other. The museum’s six works by Caravaggio, plus a few loans, have been paired off with an equivalent group by his putative modern counterpart. These pairings are not confined to a specific space, but scattered throughout the museum’s galleries. A handout defines the show’s aim as “an exceptional aesthetic experience”—so much for art history. Bacon would have relished rubbing shoulders posthumously with the greatest of the great. He would also have relished the enormous controversy in the Italian press.

A few months earlier, the Florence Accademia had launched a similar show, entitled “Perfection in Form,” which pitted Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs against “iconic Renaissance masterpieces” by Michelangelo, etc. The show has been so successful that its run has been extended. Setting twentieth-century kinkmeisters against Renaissance masters has evidently paid off, and attracted a vast new public into museums they might not have otherwise visited.

However, wouldn’t it be more useful to measure Bacon against a predecessor of his own stature and genre: for example, Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), someone he went out of his way to denounce and disassociate himself from? (“Banal” was the epithet Bacon used in the interviews with Sylvester; what he probably meant was “illustrative.”)Bacon was determined to prevent people realizing how indebted he was to this Swiss-born Londoner. Fuseli was a somewhat conventional manipulator of paint, but he was also one of the most spectacular draftsmen of the second half of the eighteenth century. And in many respects his neoclassical imagery was every bit as focused on the subconscious, every bit as sadomasochistic and fetishistic as Bacon’s. A master of theatrical effects, Fuseli had the courage to use his perverse sexuality to express a view of life that corresponds in certain respects to his virtual twin, the Marquis de Sade. Fuseli’s obsession differed from Bacon’s in that it involved women rather than men, but their exhibitionistic responses to the imagery of their respective times was uncannily close.

After his death, Victorian prudes saw to it that Fuseli’s work was suppressed. A century would pass before scholars rediscovered it. Following his centennial retrospective in 1925, there would be successive shows in London in 1935 and 1950, at a time when Bacon was formulating his style and moving in the intellectual circles where Fuseli was revered. Another artist who suffered a similar fate was the equally histrionic John “Mad” Martin (1789–1854), whose vast, enormously popular canvasses such as The Seventh Plague of Egypt and The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah had been forgotten, only to be admired anew one hundred years later. Like Halley’s Comet, these exemplars of Romantic agony seem doomed to flash in and out of the darkness of history. Might a similar trajectory be in store for Bacon Agonistes?

This Issue

December 17, 2009