The physicist Frank Oppenheimer is remembered today, insofar as he is remembered at all, as the younger brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project scientists who built the atomic bomb. Some also recall that Frank was drummed out of academic life for lying about whether he had belonged to the Communist Party yet went on to found the Exploratorium, San Francisco’s innovative science museum. But there is far more to his story, as K.C. Cole’s able biography makes clear.

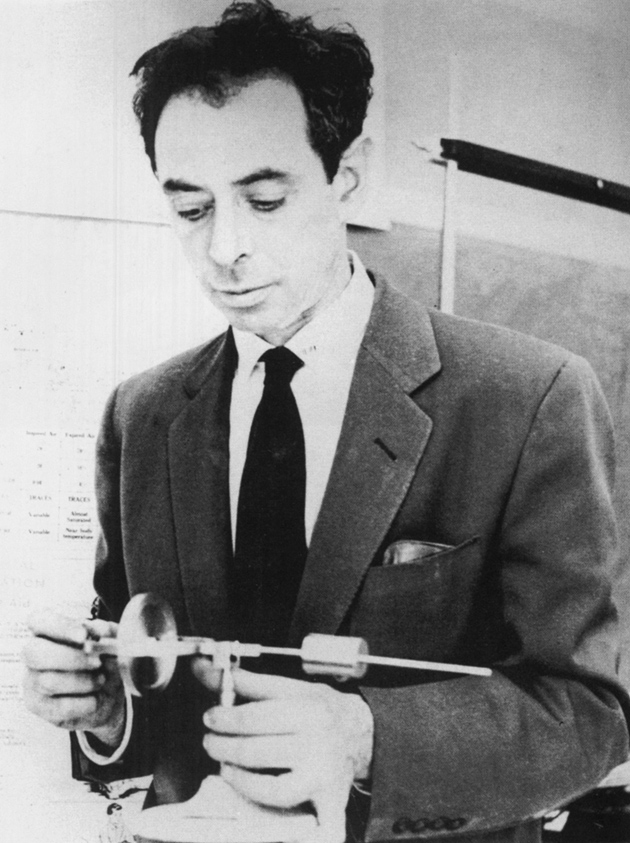

The elegant and oracular Robert Oppenheimer was a theorist whose conspicuously cultivated mien played well among those who assume that intellectual progress is mainly a matter of great thinkers thinking great thoughts. Frank was an experimenter—plainspoken, handy at fixing things, and so unconcerned about appearances that he habitually erased blackboards with his necktie. Science owes at least as much to its experimenters as to its theorists but old habits of mind are slow to change, so experimental physicists are still often overlooked and underrated. For this and other reasons Frank was obscured by his older brother’s long shadow even before the Bomb made Robert world-famous. This elision Cole is at pains to repair.

The Oppenheimer brothers grew up in a well-off, cultured household on 88th Street and Riverside Drive where the windows looked out on the Hudson River and the walls were adorned with paintings by Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Renoir, and Picasso. Their mother, Ella Friedman, had been a painter—she studied in Paris and taught at Columbia—but gave it up upon marrying Julius Oppenheimer, who had emigrated from Germany at age seventeen and made a fortune importing suit-lining fabrics. The family had a chauffeured limousine, a waterfront summer house in Bay Shore, Long Island, and a forty-foot yacht, the Lorelei.

Robert, who characterized himself as having been “an unctuous, repulsively good little boy,” became an intellectual athlete who read the Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit and, when invited to speak in the Netherlands, elected to give his lectures in Dutch although he had never studied that language. Frank was another matter. He inherited his mother’s beauty—the physicist I.I. Rabi described the cherubic young Frank as something “out of an Italian painting”—and was sufficiently artistic to consider a career as a classical flutist, but he was happiest welding, taking things apart, and conducting electrical experiments. He liked to climb trees during lightning storms and once threw a bicycle across the third rail of a train track just to see the sparks fly. Dexterous and grubby, accustomed to using words literally rather than spinning glittering metaphors, Frank was not thought brilliant. When the brothers were at Caltech in 1939, a fellow student recalled, Robert was “always at the center of any group—smooth, articulate, captivating,” while Frank “stood at the fringe, shoulders hunched over, clothes mussed and frayed, fingers still dirty from the laboratory.” Many who knew Frank Oppenheimer would agree with the colleague who called him “an ordinary, friendly guy.” Few would have said that of Robert.

The contrast between the two brothers was underscored when they worked together on the Manhattan Project. Frank was what he called a “safety inspector,” seeing to it that workers wore their hard hats and studying the winds to see which way the fallout would drift from the test site. Robert drove the science to its successful completion but made sure that everyone knew that he felt conflicted about it. Watching the world’s first atomic bomb explode at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, Robert mused over lines from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Recalling that moment years later, he added, “I suppose we all felt that, one way or another.”

If Frank felt that way he didn’t say so. Cole reports, however, that every year on August 6, the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, Frank

would sink into a profound funk, drinking whiskey from the bottle he kept in a drawer of the desk in his smoke-filled office. He rubbed his forehead, hard, as if he were trying to erase something deep in his mind. He was grim, tense, quiet; he looked as though he’d been up all night.

After the war Robert soared across the public consciousness like a figure out of Vedic mythology, seeming to embody both the bright side of science as a way of learning and its dark side as an agency of lethal power. During a White House visit in the fall of 1945, he said to President Harry S. Truman, “I feel I have blood on my hands.” Truman, who unlike Oppenheimer actually had to decide whether to drop the bomb, told Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson, “I don’t want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again.”

Advertisement

Frank, meanwhile, quietly went back to doing experimental physics. His particular interest was the study of cosmic rays—high-velocity particles from space that, upon hitting the earth’s upper atmosphere, set off cascades of reactions, making them a poor man’s version of today’s costly accelerators. But in July 1947, just a few months after joining the faculty at the University of Minnesota, Frank became the subject of a story in the Washington Times-Herald headlined, “U.S. Atom Scientist’s Brother Exposed as Communist Who Worked on A-Bomb.”

That Frank Oppenheimer had once belonged to the Communist Party was true. In 1937, while he was completing his Ph.D. at Caltech, he and his wife, Jackie Quann, involved themselves in local reform efforts such as attempting to desegregate the Pasadena public swimming pool—in those days open to nonwhites only on Wednesdays, after which the water was drained and replaced—and they joined the Party at Jackie’s urging. Frank soon made a nuisance of himself, complaining that although the Party claimed to follow “democratic centralism,” “there was centralism, but no democratic.” He quit the Party three years later.

Now, advised by the university administration that he had to make a statement, Frank denied the entire newspaper account, saying that he had “never…been a member of the Communist Party.” “It was a dumb thing to do,” he told Cole, adding that he had feared that admitting the truth “would affect my brother.” But he stuck to his story even when twelve of his new colleagues at Minnesota went out on a limb on his behalf, declaring in a statement, “Our confidence in the personal integrity of Dr. Oppenheimer is so great that we do not question his denial.” Not until June 1949, when Frank and Jackie were summoned to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, did Frank admit that he had lied. Obliged to resign from the faculty, he left the university president’s office in tears. When he and Jackie testified under oath at the HUAC hearing, they answered questions about their own affairs but refused to talk about their friends—thus taking a principled position that resulted in their remaining under FBI surveillance for many years thereafter.

In professional physics, as in professional golf or tennis, you cannot leave the game for long and expect to return at a competitive level. Denied a passport and effectively barred from academic life—university officials who considered hiring him were promptly warned by government agents that they were asking for trouble—Frank accepted the fact that his career as a research scientist was over. He and Jackie sold a Van Gogh, bought a ranch in Colorado, and spent almost a decade raising cattle. “Thus did the gentle Jewish intellectual from Manhattan wind up settling in the land of pioneers and homesteaders in a primitive cabin where the nearest neighbor was a mile away,” Cole writes. “For the locals, it was as if aliens had landed.”

A neighbor recalled that Frank “was skinnier than a rail” and that “both he and Jackie swore like sailors. And they were atheists!” Another rancher successfully opposed Frank’s bid to join the local school board, protesting, “It’s a fine thing when they have to have a Communist on the school board!” But when Frank later explained that he was not a Communist, the rancher politely apologized: “Oh, I’m sorry, I thought you were.”

The couple worked hard—Frank described his labors as “one continual job of trying to undo the property of nature to increase entropy”—and lived so rudimentarily that the FBI agents who paid regular visits to the ranch took to doling out spare change to their son Mike. The agents wanted to know whether “we were doing any experiments” to “communicate with the enemy,” Oppenheimer recalled. “But I didn’t try to do any physics.” As always, though, Frank was happy working with his hands. “I think that if you’ve been beat up by your nation for your political beliefs and you’ve built an atomic bomb and seen it used on 200,000 civilians,” he said, “and after a career of cosmic ray research you find yourself shoveling horseshit up in the mountains of Colorado…it really is a pretty good way to figure out what’s important in life.”

By 1957, having taken correspondence courses to gain a teaching certificate, Frank had become a full-time high school science teacher in nearby Pagosa Springs, Colorado, population 850. He took his students to junkyards to investigate how machines work, bought a secondhand microscope so they could study algae growing in hot springs, and once spent a class playing them a recording of Beethoven’s string quartet Op. 131, over and over. “We all felt we were experiencing something we’d never experienced before,” one of his former students recalls. “Everything in science we could get our hands on we would read, because of him. Any book that he carried I would immediately go out and buy.” Soon his students were winning awards at state science fairs and being admitted to Ivy League universities. Frank earned a reputation as a born teacher.

Advertisement

In 1961, buoyed by endorsements from the eminent physicists Hans Bethe, George Gamow, and Victor Weisskopf, Frank was hired as an associate professor at the University of Colorado. Physics had by this time pretty much passed him by—he’d written touchingly to Robert Wilson, the architect of Fermilab, asking “what new insights you have of the beauty and order of nature”—but the new post was to center on teaching, not doing. He consoled himself by lamenting what he took to be an emerging atmosphere of “cutthroat competition” in science. “I don’t want to disparage fame and the high living that often comes with it,” he wrote in an unpublished essay. “I just don’t think that scientific discovery is the place to try and find it.” He busied himself constructing experimental apparatuses designed to convey scientific concepts. This “library of experiments,” as he called it, became the basis of the science museum he called the Exploratorium.

Frank and Jackie moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s, where—at the suggestion of the San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen—he wrote a “Rationale for a Science Museum” and went to work raising funds. By May 1969 he had obtained a dollar-a-year lease from the city on Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts, built for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition. The Palace had fallen into disrepair, its enormous interior space having most recently served as an army garage and a Christmas-tree sales lot. Constantly smoking and nipping on whiskey from the bottle concealed in his beat-up old desk, Frank built dozens of apparatuses while gleaning others from colleagues, corporations, and war-surplus outfits. “Let’s get stuff in here,” he would say. “We gotta make it look like we need the space.”

He insisted that the Exploratorium’s workshop be located near the entrance and have no walls, so that visitors could see exhibits being built and repaired and “smell the oil from a lathe.” “We both agreed that physics was grubby,” said Stanford’s Wolfgang Panofsky, one of the many major scientists Oppenheimer dragooned into helping him build the Exploratorium:

It shouldn’t be pretty and under glass. The visitor should learn that experiments break, and fail, and you’ve got to fix it. Shops should be part of the museum. Because that is the way that physics is done. Things break. You fix them. You repair them. You change them. You improve them.

Oppenheimer called the Exploratorium “a kind of woods of natural phenomena,” a place where you went more to explore than to have things explained to you. He liked to say that he built it for the same reason that people build parks—because there aren’t enough trees around—and insisted that it have no guards and as few rules as possible. Children should be free to run around as they pleased; if they broke something, so what? “The whole point of the Exploratorium,” he said,

is to make it possible for people to feel they can understand the world around them. I think a lot of people have given up with that understanding—and if they give it up with the physical world around them, they give it up with the social and political world as well.

Today the Exploratorium employs three hundred people, hosts over a half-million visitors a year, and has been more or less cloned in Beijing, Paris, Tokyo, Moscow, and scores of other cities. Alan Friedman, director of the New York Hall of Science, calls it “the most influential museum in the history of the world.”

Yet it is not really a museum, and it is not exactly about science. As its motto, “Dedicated to Awareness,” suggests, the Exploratorium works mainly to subvert naive-realistic views of perception. It conveys scientific concepts, to be sure, but the principal effect of its many mirrors and lenses and spinning wheels is to make people realize that perception is itself a kind of a theory, and like all theories is vulnerable to disproof by experimentation. Kids love it, perhaps because growing up is largely a matter of correcting flaws in one’s perceptions. Adults more invested in defending their worldview can find it challenging. “That was intense,” said a young mother who I saw emerging with her two children after a recent visit. Her children said they wanted to come back right away.

K.C. Cole, a respected science writer now on the faculty at the Annenberg School of Journalism at USC, met Frank Oppenheimer when she was twenty-six years old and worked for him until his death thirteen years later, in 1985. She knew him and Jackie well, sometimes stayed at their house, and is not reticent about recounting Frank’s flaws along with his accomplishments. It is unlikely that anyone will ever write a more perceptive biography of Frank Oppenheimer.

If Cole’s book has any flaws—apart from a self-promoting foreword by the physicist Murray Gell-Mann, who boasts in its first sentence of having “helped Frank Oppenheimer obtain a critical million-dollar grant…for his fledging Exploratorium”—they arise from what Cole describes as her being “deeply addicted to Frank’s way of thinking.” One result is that the book sometimes lapses into old-left political assumptions absorbed from Frank Oppenheimer and not freshly appraised. When Cole writes that “by the 1960s, the government was already spending more on nuclear arms than on schools,” she means the federal government, but that’s not how Americans fund their public schools. Taking state and local funding into account, Americans spend ten times as much on education as on nuclear arms. As Joseph Alsop—an outspoken defender of Robert Oppenheimer—put it at the time of the HUAC hearings, Frank could be “as silly about politics as he is clever about physics.”

Still, when we consider that Robert Oppenheimer’s greatest accomplishment was to build a bomb that just about everybody wants there to be fewer of, while his younger brother advanced techniques in science education that almost everybody wants there to be more of, we may wonder which brother will, in the long run, have the more enduring legacy.

This Issue

March 25, 2010