Even a reader with some knowledge of the history of modern Germany might well draw a blank at the name of Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, the man at the center of Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s unusual and fascinating new book. From 1930 to 1934, Hammerstein was Chief of Army Command, the highest-ranking officer in the Reichswehr, as Germany’s army was known under the Weimar Republic. He was also an undisguised opponent of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. Yet he does not figure in the military or political history of the period nearly as prominently as some other generals—like Kurt von Schleicher, Hammerstein’s friend and political ally, who was the last chancellor of the Republic before Hitler, and was killed during Hitler’s “Night of the Long Knives” in 1934.

Nor, on the other hand, does Hammerstein share in the honor due to the July 20, 1944, conspirators, whose plot to assassinate Hitler came close to success. Hammerstein was involved in the long-brewing conspiracy: one of the many documents reproduced by Enzensberger is a memo delivered to Martin Bormann a few days after the failed coup, which noted that some of the leading conspirators met at Hammerstein’s home in 1942. But by the time those plotters—again, a largely aristocratic group of officers, including Henning von Tresckow and Claus von Stauffenberg—brought themselves to act, Hammerstein had been dead for more than a year. Remarkably, for a man with such powerful enemies, he died of natural causes. At his funeral, his family declined the usual military honors, because they refused to allow the swastika flag to be draped on his coffin.

If Hammerstein played a comparatively small historical role, why did Enzensberger—Germany’s leading poet and man of letters, now eighty years old—think him deserving of a book? The reason, he writes, is that Hammerstein’s life “says a great deal about how one could survive Hitler’s rule without capitulating to it.” The quality that made this possible comes across more clearly in the book’s original German title—Hammerstein oder Der Eigensinn—than in the English translation by Martin Chalmers, The Silences of Hammerstein. Eigensinn can be translated as stubbornness or obstinacy, but in this case it carries a more positive connotation than those words usually do. The book’s French title, Hammerstein ou l’intransigeance, seems to come closer to Enzensberger’s meaning.

In writing about Hammerstein, Enzensberger is not just telling the story of a man, or of that man’s remarkable family. He is investigating the moral value of intransigence—the combination of principle, arrogance, and willfulness that prevented Hammerstein from falling into line with Nazism, when so many of his fellow officers did. For this reason, Enzensberger eschews the usual conventions of biography: the book proceeds in short narrative sections, often out of chronological order, interspersed with documents and passages of analysis and rumination. There are even imaginary, posthumous interviews with people Enzensberger is writing about, in which he can speculate on their true motives. Indeed, the book’s idiosyncratic power comes from the fact that it is not just a work of history, but a record of the author’s struggle to understand and judge that history.

Intransigence is valuable, Enzensberger suggests, precisely because it is a more equivocal virtue than heroism. No word but heroism will do for someone like Sophie Scholl, the twenty-one-year-old college student who invited death by distributing anti-Nazi leaflets in Munich in 1943, and went to her beheading with the words, “What does my death matter, if by our action thousands of people will be awakened and stirred to action?” But that kind of heroism is almost miraculous, and it would be terrifying to think that the power of any given society to resist evil is dependent on miracles.

Hammerstein, on the other hand, once told a friend who was pressing him to act against Hitler, “I’m not a ‘hero’—there, you’re mistaken in me. I stand my ground, if I have to. But I don’t shove my way to the wheel of history….” This seems like a more attainable standard, a kind of realism not untainted by selfishness, which, if it cannot achieve moral greatness, might at least be enough to stave off moral collapse. Enzensberger’s praise of such intransigence goes along with his conviction that if contemporary readers were faced with the kind of dilemmas and disasters that Hammerstein’s generation had to negotiate, we would not emerge with more credit. When examining “the horrors of the Weimar Republic,” as Enzensberger titles one section, “we should be grateful that we weren’t there.”

We should, of course. As Bertolt Brecht wrote in “To Those Born Later”:

You who will emerge from the flood

In which we have gone under

Remember

When you speak of our failings

The dark time too

Which you have escaped.

But is Kurt von Hammerstein the right person to impart this lesson? In a dialogue with the Spanish writer Jorge Semprún, recently published in Le Nouvel Observateur, Enzensberger remarked that Hammerstein “was neither an ideal nor a martyr,” but “someone who behaved in a way that was…very acceptable.” Our feelings about Hammerstein, and about The Silences of Hammerstein, stand and fall with the validity of that judgment. Are we entitled, from our comfortable historical distance, to say no more than that Hammerstein’s silences were acceptable? Or is it possible that his very willingness to consider silence a form of resistance was the form that his collaboration with Nazism took? Is Hammerstein one of those who deserve pity for living in what Brecht calls “dark time,” or did he in fact make them a little darker?

Advertisement

In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Kurt von Hammerstein turned fifty-four years old. His military career had begun at the age of nine, when he enrolled in cadet school—at least in part, Enzensberger writes, because his ancient but impoverished family could not afford any other kind of education. Whether the boy wanted to become a soldier or not—“it is said he would rather have been a lawyer or a Bremen coffee trader”—Hammerstein passed through the most prestigious military institutions in Wilhelmine Germany. After attending the Central Cadet School at Lichterfelde, he became an officer in the Third Guards Foot Regiment—Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg’s old unit—and by the time of World War I he was a captain on the elite General Staff. Along the way, he married Maria, the daughter of Baron Walther von Lüttwitz, a senior general who opposed the marriage on the grounds of Hammerstein’s poverty.

In the turmoil that followed Germany’s defeat in 1918, both Hammerstein and his father-in-law played significant roles. Hammerstein was one of the so-called “three majors” who “had a great, perhaps even dominant influence on all important issues linked to military matters.” As Enzensberger puts it, this small group (which also included Kurt von Schleicher) “prevented a descent into chaos” during the establishment of the Republic in 1918–1919. Lüttwitz, on the other hand, was an open enemy of the Republic. One of the most hated provisions of the Treaty of Versailles was its restriction of the Reichswehr to 100,000 men—a measure that, along with the banning of heavy artillery and military aviation, was meant to destroy Germany’s potential for aggression.

In March 1920, when Lüttwitz was commandant of Berlin, he was ordered to disband the Ehrhardt Brigade—a Freikorps unit of nationalist veterans—in accordance with the treaty. He refused, and instead lent his support to a coup that aimed to make the right-wing politician Wolfgang Kapp chancellor. This rebellion, which succeeded in driving the legal government from Berlin before it was put down a few days later, has gone down in history as the Kapp Putsch, but Lüttwitz was the driving force behind it.

Notably, when Lüttwitz attempted to enlist his son-in-law in the coup, Hammerstein refused. Instead, he chose to work within the established system, and rose over the next ten years to become chief of the Troop Office—the Reichswehr’s equivalent of a general staff, which was also prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles. In 1930, he was promoted to the highest army command. Yet as Enzensberger points out, the leadership of the Reichswehr was no more resigned than outright rebels like Lüttwitz to the Versailles settlement. On the contrary, during the 1920s, every stratagem was undertaken to rearm Germany illegally—including a close collaboration with the Soviet Union.

It is a measure of the bewildering political cynicism of the period that even as the Comintern was fomenting armed uprisings in Germany, the Reichswehr was helping to train the Red Army and building arms factories on Russian soil. Enzensberger quotes Karl Radek explaining that General Hans von Seeckt—one of Hammerstein’s predecessors as army chief—“declared that it is necessary to throttle the Communists in Germany but to make common cause with the Soviet Union.” Hammerstein himself was deeply involved in this secret collaboration, and spent part of 1929 touring German installations in Russia, even befriending General Kliment Voroshilov, the future Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Hammerstein’s Russian experiences are a reminder of his entire willingness to use illegal means to strengthen Germany militarily, and of his essential contempt for the Versailles settlement—sentiments that he shared, of course, with every Reichswehr officer. It was precisely their commitment to rearmament, if not actual revanchism, that left Germany’s officer corps in such a weak position to resist the rise of Hitler and the Nazis. For as Hammerstein himself said in September 1930, “Apart from the pace, Hitler actually wants the same thing as the Reichswehr.” And unlike any of the Weimar generals or politicians, Hitler actually delivered it: by 1935 he had repudiated Versailles and openly launched a program of rearmament.

Advertisement

These successes, for almost all German officers, were more important than the things they disliked about Hitler—his plebeian background and manners, his radical populism, his obsessive anti-Semitism. (On this last count, it was the obsessiveness more than the anti-Semitism that bothered aristocrats like Hammerstein, who joked in 1931, “I hope we’ll soon be rid of this Hitler, so that I can insult the Jews again.”) And the same pattern is manifest in the whole history of the officer corps’s relations with Hitler—a story that necessarily goes beyond the scope of Enzensberger’s book. On each occasion when senior officers plotted to resist or overthrow Hitler, it was not because they objected to his basic goals, but because they feared his tactics and pacing. They rebelled, or talked about rebelling, on prudential grounds, not principled ones.

Thus in September 1938, when it seemed that Hitler was about to invade Czechoslovakia, a few generals discussed launching a putsch in order to stop a war they believed Germany could not win. They were assuming that France would go to war to defend its Czech ally; but when the Munich agreement came, rewarding Hitler’s gamble, the plotting stopped. Not until July 1944, when the war was clearly lost, did a military rebellion actually take place, and even then it was a small, desperate affair. As Telford Taylor, the Nuremberg prosecutor, wrote:

It was the wide area of agreement on objectives between Hitler and the generals that brought them together. Having become a pillar of the Third Reich, they were disinclined to bring the edifice crashing down about their own ears.

How does Hammerstein fit into this inglorious picture? His most significant attempt to stop Hitler came at the end of January 1933, a few days before the Nazis took power. Schleicher was on the way out as chancellor, and it was rumored that the aged President Hindenburg was going to appoint Hitler to replace him. Hammerstein visited Hindenburg and told him—“calmly and matter-of-factly”—that he had “misgivings with respect to a possible appointment of Hitler as Reich Chancellor,” in particular because of the effect it would have on the army. Allegedly, Hindenburg replied that “he had no intention whatsoever of making the Austrian corporal defense minister or Reich chancellor.” This meeting took place on January 26, 27, or 28, depending on which source you follow; on the 30th, Hindenburg broke his promise and appointed Hitler.

And with that, Hammerstein’s efforts came to an end. He and Schleicher “considered whether we knew any means to influence the situation…. The result of our reflections was negative.” Over the next year, as the Nazis tightened their grip on power, Hammerstein was effectively sidelined, and at the end of 1933 he submitted his resignation. As Enzensberger puts it, “There were good reasons for General von Hammerstein having had enough of his post.” When Hindenburg sent him a signed photograph to mark his retirement, Hammerstein tore it up and threw it away.

But tearing up a photo is a merely symbolic gesture, and it was in his gestures and comments that Hammerstein’s opposition to Hitler would remain. Enzensberger records several of his dismissive, cutting remarks about the Nazis: when he heard about the Reichstag fire, for instance, he said, “I wouldn’t be surprised if they set it alight themselves.” But no more than any other leading general did Hammerstein make a public protest. Even after his friend Schleicher was murdered, Hammerstein did not renounce his rank and pension, emigrate, or organize an active resistance. There is nothing in Enzensberger’s account to make one disagree with the verdict Telford Taylor rendered almost sixty years ago:

At no time…did Hammerstein embark on a methodical course of action to provide his anti-Nazi bark with a bite…. Hammerstein thought he could overthrow Hitler merely by being vocally anti-Nazi, and as a result…he accomplished nothing whatsoever.

In 1939, when Hitler was preparing to invade Poland, he called Hammerstein back to active duty and gave him a command on the Polish front, then moved him to Germany’s western border. It is unclear why Hitler turned to a man he disliked and distrusted, and by the end of September Hammerstein had been sent back into retirement. What is significant, however, is that Hammerstein agreed to serve under Hitler in an aggressive war of conquest. “I knew hardly anyone who so overtly rejected the regime, without any caution, without any fear,” recalled one of his friends after his death. But for all his private opposition, he was sufficiently in agreement with Hitler’s goals to fight for them—as was also true of the July 20 plotters.

Hammerstein’s career seems to confirm the view of Hans Mommsen that “the step from partial criticism of the National Socialist system to out-and-out resistance could only be taken by people who, like the communists and leftwing socialists, were able to resist the pressure of the Hitler-myth, from strong ideological and political convictions.” He could have added such religious dissenters as Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was executed in 1945, and Pastor Martin Niemöller, who was interned in Sachsenhausen and Dachau between 1938 and 1945. Another way of putting this is that intransigence, Eigensinn, is not a strong enough lever with which to move the world. There must be what Mommsen calls an “alternative utopian vision,” and the militarist nationalism of Hammerstein could not provide it. That was not just his fault, but a sign of the moral bankruptcy of his caste and profession, which bred Hammerstein not to be “acceptable” but to be a leader—and which indeed followed his lead when he acquiesced, albeit with bad grace, to the Third Reich.

The Silences of Hammerstein is not just about Kurt von Hammerstein, however. It is also about his children, who demonstrated “strong ideological and political convictions” to an almost fantastic degree. Kurt and Maria were married in 1907, and over the next fifteen years they had four daughters and three sons. The three oldest—Marie Luise, Maria Therese, and Helga—were born shortly before World War I, which meant that the years of their growth and education were precisely the years of Germany’s defeat and Weimar’s economic and political turmoil. Thomas Mann’s story “Disorder and Early Sorrow,” with its portrait of a family turned upside down by hyperinflation and social change, may be the best guide to the spiritual atmosphere in which the Hammerstein children were raised.

For all young Germans of that generation, the gap between their parents’ Germany and their own was hard to bridge. How much more difficult it must have been to be the daughter of a man like Hammerstein, who virtually incarnated the old order, can be glimpsed in the recollections Enzensberger quotes. His daughters described him as “the last ‘grand seigneur,'” and remembered one occasion when he hit two of the girls with his riding whip. His saving grace as a father, however, was a remarkable permissiveness, which took the form of not caring, or even knowing, what his children were up to. This seems, in part, like Hammerstein’s usual ironic detachment, but Maria Therese also saw it as an expression of his “unshakeable confidence” in his children. “My children are free republicans. They can say and do what they want,” he declared.

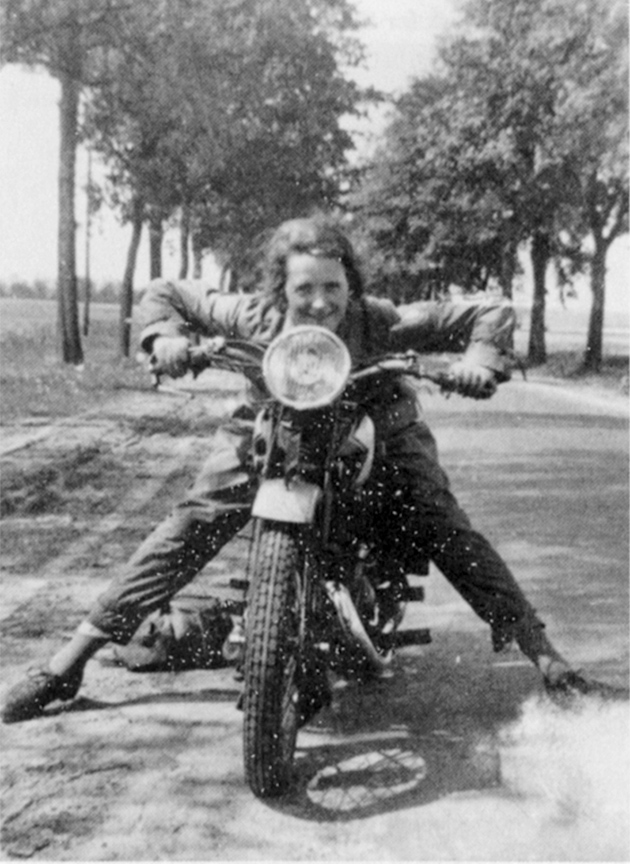

Some of what they wanted to do was the typical rebellion of their time and place. You could hardly find a better icon of Weimar’s “new woman” than the photograph of Maria Therese straddling a motorcycle, gleefully unladylike, careening into the future. More serious, in their milieu, was the girls’ predilection for Jewish friends, which went hand in hand with their growing interest in radical left-wing politics. In 1927, Marie Luise fell in love with Werner Scholem, a Spartacist and Communist member of the Reichstag. (The brother of the scholar Gershom Scholem, Werner was killed in Buchenwald in 1940.) Soon after, fifteen-year-old Helga became involved with Leo Roth, a man of many pseudonyms, who was part of the German Communist Party’s “M-Apparat”—an espionage group that reported directly to Moscow.

In a novel, one would hardly be able to accept the idea that two daughters of Germany’s commander in chief could become Communist spies. Yet as Enzensberger leads us through the murky historical records, the fact becomes clear. On February 3, 1933, for instance, Hammerstein hosted a meeting between Hitler and a group of generals, in which the new chancellor outlined in detail his plans for dictatorship and war. “I set myself the term of six–eight years in order to eradicate Marxism completely. Then, the army will be capable of conducting an active foreign policy, and the goal of the expansion of the living space of the German people will also be achieved by force of arms,” Hitler explained, in an uncannily accurate timeline.

We know more or less exactly what he said because, as Enzensberger shows, just three days after the meeting a complete transcript of Hitler’s speech was radioed to Moscow. How could such a stupendous breach of security have taken place? According to Leo Roth, it was because Marie Luise and Helga had hidden behind a curtain and taken down Hitler’s words in shorthand. Enzensberger considers this “hardly conceivable…one of those legends in which oral transmission is so rich.” But it is quite conceivable that Hammerstein kept a transcript in his office safe, and that Helga managed to steal and copy it for the M-Apparat. Enzensberger even speculates that Hammerstein, remembering his cordial relations with the Red Army, connived at this espionage, hoping that “Hitler’s speech could have served as a warning to the leadership in Moscow.”

Here as at many other points in The Silences of Hammerstein, Enzensberger makes clear to the reader just how hard it is to ascertain the truth about even the recent past—especially when dealing with a world of professional spies and ideologues. What is certain is that the Hammerstein children were living out their opposition to Nazi Germany in a way that their father never quite did. Maria Therese, for instance, ended up marrying a man named Joachim Paasche, who was part Jewish, and in 1934 they moved to a kibbutz near Tel Aviv. (They stayed only a little while before moving to Japan, where they lived until after the war.)

Enzensberger notes that Paasche’s father, who had been a pacifist during World War I, was murdered in 1920 by a right-wing gang, and that the children heard his killers singing, “Black-white-red ribbon, swastika on helmet/the Ehrhardt Brigade is what we’re called.” Of course, the Ehrhardt Brigade was the unit employed by Maria Therese’s grandfather, Baron Walther von Lüttwitz, during the Kapp Putsch. Could her marriage be seen as a kind of reparation, or at least a statement of defiance?

Certainly her younger brother Ludwig made his convictions clear when, on July 20, 1944, he was an aide-de-camp to the coup plotters in Berlin. Their nerve center, in fact, was the very same building in the Bendlerstrasse—the military district—where Ludwig had grown up. More, the room from which the rogue generals directed operations had once been Kurt von Hammerstein’s dining room. That is, it was the very same room in which Hitler had informed the Reichswehr (and, unintentionally, the Comintern) of his plans eleven years earlier. This childhood knowledge stood Ludwig in good stead when it turned out that Hitler had not been killed, enabling him to escape with his life. In one of his “posthumous conversations,” Enzensberger has Ludwig say, “Of course, I knew every passageway, every flight of stairs in the building, because I had lived and played there as a boy.” In this way, too, Hammerstein’s children lived by embracing and flying from his legacy.

This Issue

June 10, 2010