1.

In 1996, the Mexican historian Jean Meyer asked me to translate a poem by the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam (born in Warsaw in 1891; died in the Vtoraya Rechka transit camp, near Vladivostok, in 1938). The poem was the celebrated “Epigram Against Stalin,” which begins with the line “My zhivem pod soboiu ne chuia strany” (“We live without feeling the country beneath our feet”). In 1980, I’d moved from Havana, my birthplace, to Siberia to study engineering at the University of Novosibirsk, and like anyone else who lived in Russia through the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, I knew the poem well. I had often recited it aloud in admiration of its formal qualities, in particular that first line, whose words have an almost magical force.

No version of the poem then existed in Spanish; the French translation that had just appeared in Vitaly Shentalinsky’s La parole ressuscitée made so impoverished a contrast to the extraordinary beauty of the original that I immediately began translating a more satisfactory variant, trying to capture the poem’s charm while preserving its severe gravity. I worked on it for several days and came up with a translation that Jean Meyer included in his history of Russia and its empires, and that I posted on the wall over my desk.

The poem had cost Mandelstam his life; writing it was an act of incredible recklessness, bravery, or artistic integrity. In the years since, I’ve never stopped thinking about it, and one thought has never left me in peace: though I labored long and patiently over my translation, I wasn’t at all satisfied with the results. The poem simply would not take; the translation felt like a pallid copy of the original Russian, which is as beautiful and powerful as if it had been carved in stone. Unlike the work of Joseph Brodsky, whom I’ve also translated extensively, Osip Mandelstam’s poetry is amazingly concentrated and not particularly discursive. It was virtually impossible to translate its sonorities, or the richness of many images that don’t come through or resonate in the target language—in my case, Spanish. As the poem moves from one language into another, the aura of meaning and allusion that was absolutely transparent to the Russian listeners is lost. It’s as if the poem were a tree and we could only manage to transplant its trunk and thickest limbs, while leaving all its green and shimmering foliage in the territory of the other language.

In any case, my translation of Mandelstam’s poem was well received. Years passed without my looking at the translation again until recently, when I had the idea of including it in a personal anthology of Russian poetry I’m working on. After an attentive rereading I didn’t think it was possible to change any of the solutions that in their moment I had hit upon, but I decided it would be fitting to add some commentary, as another way of transmitting that halo of meaning.

In Russia, the poem is known as the “Epigram Against Stalin,” a title some consider inadequate and belittling. Others say the title resulted from a maneuver by Mandelstam’s friends (among them Boris Pasternak) to make the poem seem nothing more than a kind of pithy, off-the-cuff quip meant to sting or satirize, in the genre that found its highest expression in Martial, the Latin poet of the first century AD.

Described by one critic as the sixteen lines of a death sentence, this is perhaps the twentieth century’s most important political poem, written by one of its greatest poets against the man who may well be said to have been the cruelest of its tyrants.

2.

Мы живем, под собою не чуя cтраны,

Наши речи за десять шагов не слышны,

А где хватит на полразговорца,

Там припомнят кремлёвского горца.

Его толстые пальцы, как черви, жирны,

А слова, как пудовые гири, верны,

Тараканьи смеются усища,

И сияют его голенища.А вокруг него сброд тонкошеих воҗдей,

Он играет услугами полулюдей.

Кто свистит, кто мяучит, кто хнычет,

Он один лишь бабачит и тычет,

Как подкову, кует за указом указ:

Кому в пах, кому в лоб, кому в бровь, кому в глаз.Что ни казнь у него—то малина

И широкая грудь осетина.EPIGRAMA CONTRA STALIN Vivimos sin sentir el país a nuestros pies,

nuestras palabras no se escuchan a diez pasos.

La más breve de las pláicas

gravita, quejosa, al montañes del Kremlin.

Sus dedos gruesos como gusanos, grasientos,

y sus palabras como pesados martillos, certeras.

Sus bigotes de cucaracha parecen reír

y relumbran las cañas de sus botas.Entre una chusma de caciques de cuello extrafino

él juega con los favores de estas cuasipersonas.

Uno silba, otro maúlla, aquel gime, el otro llora;

sólo él campea tonante y los tutea.

Como herraduras forja un decreto tras otro:

A uno al bajo vientre, al otro en la frente, al tercero en la ceja, al cuarto en el ojo.Toda ejecución es para él un festejo

que alegra su amplio pecho de oseta.—Translated from the Russian by José Manuel Prieto

We live without feeling the country beneath our feet,

our words are inaudible from ten steps away.

Any conversation, however brief,

gravitates, gratingly, toward the Kremlin’s mountain man.

His greasy fingers are thick as worms,

his words weighty hammers slamming their target.

His cockroach moustache seems to snicker,

and the shafts of his high-topped boots gleam.Amid a rabble of scrawny-necked chieftains,

he toys with the favors of such homunculi.

One hisses, the other mewls, one groans, the other weeps;

he prowls thunderously among them, showering them with scorn.

Forging decree after decree, like horseshoes,

he pitches one to the belly, another to the forehead,

a third to the eyebrow, a fourth in the eye.Every execution is a carnival

that fills his broad Ossetian chest with delight.—Translated by Esther Allen from José Manuel Prieto’s Spanish version

3.

Advertisement

We live without feeling the country beneath our feet,

Мы живем, под собою не чуя cтраны

The first line seems to present no particular difficulty other than conveying with absolute clarity how hazardous the life of the citizens has become, the sharp danger everyone takes in with every breath. The image is amplified by the verb Mandelstam uses, which I translated into Spanish as sentir (to feel or to smell), but which in the original is chuyat’, a word whose first meaning, to sniff out or to scent, has a dimension of the hunt, the vague, peripheral perception of a wild beast detecting a predator. The entire line projects an image of a people adrift in apprehension, an existence that has lost every point of reference, even the ground beneath it; the words transmit a sensation of urgency and danger, of pursuit.

our words are inaudible from ten steps away.

Наши речи за десять шагов не слышны,

The citizens of Soviet Russia had acquired the habit of speaking in low voices for fear of being overheard; parents avoided talking about any delicate matter in front of their children; lovers feared the ear of every passing stranger. Informers such as the one who told the authorities about the epigram were a standard feature of the time. It became habitual to simply go out into the street to talk about anything, even matters of little importance.

When Isaiah Berlin visits Anna Akhmatova in postwar Leningrad, the poet points to the ceiling at the beginning of the interview to signal that someone might be listening. In Against All Hope, the memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam, Osip’s widow, the poet speaks of returning from a trip to the countryside to discover that telephones in Moscow had been smothered in pillows; a rumor had gone around that they were all bugged (which in fact would not have been possible with the technology of that era).

Another memoir, Avec Staline dans le Kremlin, by Stalin’s former secretary Boris Bazhanov, recounts that Stalin had a small personal switchboard installed in the Kremlin, which enabled him to listen in on the conversations of the other Communist leaders. One afternoon, Bazhanov, who had no prior inkling that such a thing existed, opened the wrong door and found Stalin in a small room with a pair of earphones on his head, deeply absorbed in eavesdropping on a conversation among the elite Party leaders who enjoyed the privilege of living in the Kremlin. That one glimpse was enough to precipitate Bazhanov’s escape across the Iranian border, in 1929, on foot.

Any conversation, however brief,

А где хватит на полразговорца,

In the original, literally: “when there’s enough for half a conversation” or “when we work up a short conversation” (polrazgovorets). “There’s enough” (khvatit’), which could be translated as “we work up,” alludes as much to the constant rush, the lack of time, as to the fear that is garroting everyone.

In 1934, on a visit to Pasternak’s home, Mandelstam cannot keep himself from reciting the epigram. It is an act of total insanity, for several of those present will hurry to inform the authorities. Emma Gerstein, who was very close to both Pasternak and Mandelstam, writes in her Memoirs of yet another recitation, attended by Nikolay Gumilyov’s son Lev, who would also spend many years in the gulag.

This patently suicidal conduct on Mandelstam’s part had an additional explanation: he would compose his poems in his head, and only when they were ready, after a lengthy process of intense internal labor, would he put them down on paper. Mandelstam knew that the epigram would never be published and was trying to leave it imprinted on as many minds as possible, to keep it from disappearing with his death.

gravitates, gratingly…

Там припомнят

In Russian, literally, they “mention” Stalin (pripomniat). Did he actually enjoy the blind admiration of his people that many still credit him with in those years before the Great Terror and the Moscow show trials? The verb used here, pripomniat, carries with it a trace of annoyance. You say to someone “I’ll remind you of this” (Ya tebe pripomniu!), in the sense of “you’ll pay me for this” or “I’ll get you back for this.” It isn’t merely that the dictator perpetually comes to mind, but that the thought of him is irritating.

Advertisement

During an earlier visit to Moscow that winter, Mandelstam had recited the poem in private to Pasternak, always the more cautious and astute of the two (Pasternak would die in his bed, in the privileged writers’ villa of Peredelkino). His response was:

What you have just recited to me bears no relationship whatsoever to literature or to poetry. This is not a literary achievement but a suicidal action of which I do not approve and which I do not wish to have any part in. You have not recited anything to me and I did not hear anything and I beg you not to recite this to anyone else ever.

Nevertheless, the poet did so, and on more than one occasion. One memoirist accuses him of having acted out of a terrible hatred for Stalin.

…the Kremlin’s mountain man.

…кремлёвского горца.

For an intellectual of the old school like Mandelstam (a graduate of the same elite Tenishev School in St. Petersburg attended as a boy by Vladimir Nabokov), the image of a Georgian, a “mountain man” (gorets), in the Kremlin symbolized something absolutely alien, a descent into savagery. Those who occupy the highest government positions in Soviet Russia are little more than coarse peasants. In 1921, when friends intercede for the life of the poet Nikolay Gumilyov (Anna Akhmatova’s first husband, falsely accused of participating in a royalist conspiracy and executed by firing squad), they’re surprised to discover that the presiding judge—the commissar of the Cheka, to use the revolutionary terminology—looks and acts like a dry goods merchant of the tsarist era. As the judge was confessing that there was nothing he could do to save the poet’s life, he moved his hands with the slow smooth gesture of one measuring out or assessing the quality of some fabric. But what he had in his hands was the life of Nikolay Gumilyov.

His greasy fingers are thick as worms,

Его толстые пальцы, как черви, жирны

The era’s “greatest” poet, the artist most exalted by official propaganda, was neither Vladimir Mayakovsky nor any of the other three titans of the Russian twentieth century: Marina Tsvetaeva, Boris Pasternak, or Anna Akhmatova. The proletariat’s great bard went by the name of Demian Biedny—Demian “the Poor”—and was an immensely popular versifier of Party-inspired couplets. His position within the Soviet hierarchy was such that he had an apartment in the Kremlin. He was said to be an incorrigible gambler, and would pay the debts thus incurred with slugs of gold that he cut off with pliers and weighed on a small scale placed atop the card table’s green baize. He was, accordingly, one of Joseph Stalin’s neighbors, and the dictator would sometimes borrow books from this false poet of the working classes, books he later returned, Demian had noted in his diary, with the marks of his “greasy fingers” all over the pages. Mandelstam appears to have been acquainted with the anecdote and therefore metamorphosed Stalin’s fingers into “greasy worms.”

his words weighty hammers slamming their target.

А слова, как пудовые гири, верны,

In the original, literally: “And his words like one-pood weights, on target.” Throughout his life, Stalin, who was educated for a time in an Orthodox seminary in Tiflis (the current Tbilisi), retained a strong Georgian accent. He chose his words slowly when speaking Russian, a language he came to use with some facility but that never ceased to be foreign to him. Among the accents a Russian can readily distinguish, the Georgian particularly stands out for its heaviness. Innumerable jokes are based on Georgian pronunciation, which tends to be spittingly hard and entirely insensible to the gamut of Russian phonemes.

The one-pood weights evoke another memory: during my early years as a student in Russia I used to do my morning exercises with one of them (a pood being an antique Russian unit equivalent to about thirty-five pounds). Made of cast iron in a design that goes back to the nineteenth-century craze for Swiss gymnastics, the weights are essentially cannonballs with a handle attached by which you lift the thing with one hand, then the other, right, left, right, left, taking fearful care not to let it fall onto your foot. Nowadays the old one-pood weights are no longer sold; they’ve been replaced by chrome-plated Western barbells with interchangeable disks.

His cockroach moustache seems to snicker,

Тараканьи смеются усища,

In the original, literally: “His cockroach mustache laughs.” A childish image that echoes a beloved children’s poem by Korney Chukovsky in which a “huge and mustachioed cockroach” (usatii tarakanishe) terrorizes a forest’s animals until a “brave sparrow” faces him down and gobbles him up with a single peck of its beak.

In her invaluable memoirs, Yevgenia Ginzburg relates that one day she began to read Chukovsky’s poem to the children of the kindergarten where she was working, in the distant province of Magadan. On hearing Chukovsky’s phrase “the terrible huge and mustachioed cockroach,” a colleague understood in horror what one reading of that passage might be and was on the verge of denouncing her for having read that poem aloud to the children. Since children all over Russia memorize Chukovsky’s poem even today, the Russian understanding of the Mandelstam line passes, invariably, through that locus of memory, an image at once comic and terrifying.

And the shafts of his high-top boots gleam.

И сияют его голенища.

Lenin’s attire—the Swiss burgher’s vest he hitches his thumb into as he harangues the crowd in front of the Finland Station on April 3, 1917—is visibly that of a man of peace, a civilian. It was Leon Trotsky who, in 1918, at the height of the war between Whites and Reds, had himself photographed in a get-up of leather and straps that scandalized Moses Nappelbaum, a portraitist with a studio on the Nevsky Prospekt. To Nappelbaum, whose photographs of the St. Petersburg elite, among them Anna Akhmatova herself, were famous, the militaristic garb looked like some absurd chauffeur’s uniform, inappropriate to a leader of the world revolution. The style caught on and became the distinctive uniform of the Cheka’s commissars and, in slightly altered form—high-top boots, canvas army jacket—of the entire Bolshevik leadership.

Amid a rabble of scrawny-necked chieftains

А вокруг него сброд тонкошеих воҗдей

Mandelstam uses the word sbrod, which I translated into Spanish as the pejorative chusma or rabble. According to the Russian critic Benedict Sarnov, this line almost certainly prolonged Osip Mandelstam’s life. The epigram’s first terrified audience thought Mandelstam’s arrest and execution must be imminent. Instead, Stalin ordered a measure that, within the Soviet arsenal of punishments, was fairly light: “administrative exile” to the city of Cherdin, where his wife was allowed to accompany him. Later, the punishment would be softened even further when, in 1935, the two were permitted to move to Voronezh, a small provincial city in the south of Russia with a more temperate climate.

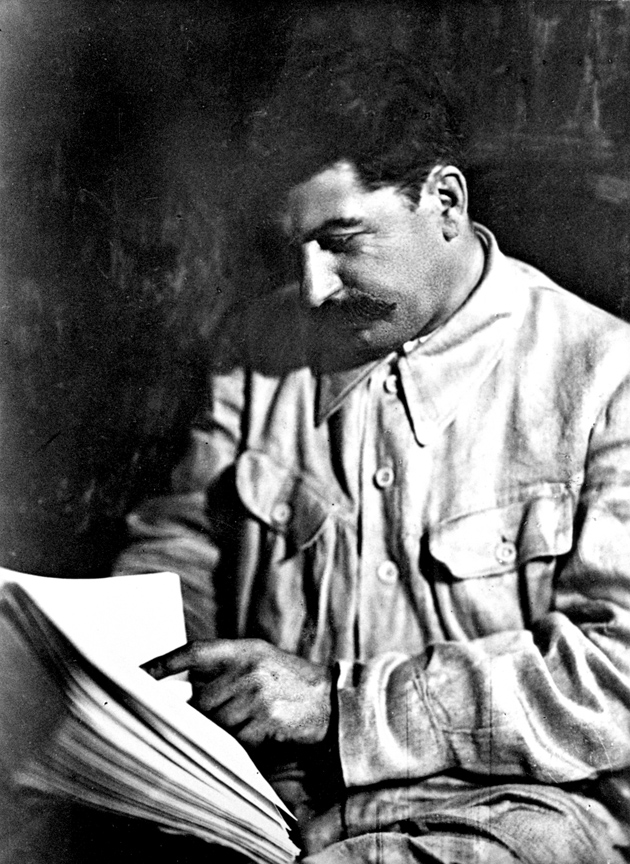

David King

One of Nappelbaum’s portraits of Stalin; from David King’s Red Star Over Russia: A Visual History of the Soviet Union from the Revolution to the Death of Stalin, published recently by Abrams. According to King, Stalin once threw Nappelbaum’s photographs on the floor in fury. ‘It was a bad idea,’ King writes, ‘to show the “Leader and Teacher” reading with his index finger when the campaign for literacy was in full swing.’

According to Sarnov, Stalin wanted Mandelstam to write a poem dedicated to him: “Stalin knew perfectly well that the opinion future generations would have of him depended to a large degree on what the poets wrote about him.” And especially Mandelstam, so perceptive that he had understood precisely the type of individual—the “scrawny-necked chieftains”—who surrounded the dictator, as well as the way he toyed with and dominated them. Such subtle understanding of the leader’s life seems to have impressed Stalin. This may explain the insistence with which, in a famous conversation, he would ask Pasternak whether Mandelstam could be considered a “true master.” His question was: “But is he or is he not a master?”

Indeed, Stalin proved to be a penetrating psychologist. For in the city of Voronezh in January 1937, Mandelstam did write a sad “Ode to Stalin” that includes this line: “I would like to call you not Stalin but Dzhugashvili.” That is to say, not the official Party pseudonym but the more human name that the man was born with, thereby approaching him from his softest, most redeemable side. It did not save Mandelstam from being transported to the gulag in which he died. A similar “commission” was given to Mikhail Bulgakov, who would also spend almost a year at the end of his life, already mortally ill, writing a play called Batum about the heroic youth of the young Yugashvili in pre-revolutionary Batumi.

Pasternak, always more subtle, sent Stalin, during the period of mourning for his wife Nadezhda Alliluyeva, a telegram, subsequently published in the Literary Gazette, which some believe saved him from the gulag: “I join in the sentiments of my comrades. I spent yesterday evening lost in long, deep thoughts about Stalin, as an artist, for the first time.” It was a veiled promise to someday use his talent to leave a “human” or literary image of the dictator.

Many years later, when I was studying in the largest technical university in Siberia, in the deep hinterlands of the Soviet Union, I spent half an hour in one of its lecture halls in conversation with the son of Lev Kamenev, one of the “chieftains” who was executed in 1936. The son had lived all those years under the false name of Glebov and had not yet emerged from his relative anonymity. I realize now, looking back at the memory, that he didn’t have the scrawny neck Mandelstam alludes to, though he did have the hairless wattles of a gospodin professor. Short and stout, he smoked incessantly in an auditorium where smoking was strictly prohibited. He was a brilliant philosophy professor and I well remember our discussion of Aristotle’s Poetics. At the end of the 1980s he reclaimed his true surname and I have since seen him interviewed about his father and himself on television, cigarette permanently in hand.

he toys with the favors of such homunculi.

Он играет услугами полулюдей.

The USSR of the 1930s saw the blossoming and expansion of a complicated system of patronage between the Party high command and the intellectual elite, described by Sheila Fitzpatrick in Everyday Stalinism (1999). It was common for writers and poets to attend the “salons” of the new governing class, and it was that sort of friendship that united Nikolai Bukharin, “the Party favorite,” and the Mandelstams. Bukharin is among those who, when the affair of the epigram explodes, first tries to intervene and then recoils from the situation in terror.

To write to Stalin, to turn to him directly and ask him to straighten out a matter of political persecution or imprisonment, had become a habit among Soviet writers who were in trouble with the state. In 1931, Yevgeny Zamyatin, author of the celebrated dystopia We (1921)—precursor to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1984—had written to Stalin asking for permission to emigrate, which was granted. Mikhail Bulgakov would also write with the same request, but his petition was rejected.

Curiously, in Mandelstam’s case, it is Stalin himself who decides to call Pasternak, with the clear intention of interceding on the poet’s behalf, and even throwing in Pasternak’s face the fact that he and his colleagues have done nothing to save Mandelstam. What takes place then is the famous conversation in which the dictator, above and beyond all else, wants to know the opinion that Pasternak and his fellow writers have of Mandelstam’s skill as a poet. The conversation takes place at 2:00 AM. Pasternak is in his dacha. The phone rings.

Stalin: Mandelstam’s case is being analyzed. Everything will be worked out. Why haven’t the writers’ organizations come to me? If I were a poet and my friend had fallen into disgrace, I would do the impossible [I would scale walls] to help him.

Pasternak: Since 1927, the writers’ organizations have no longer dealt with such matters. If I hadn’t taken steps, it’s unlikely you would ever have learned of the situation.

Stalin: But is he or is he not a master?

Pasternak: That is not the issue!

Stalin: What is the issue then?

Pasternak: I would like to meet with you…and for us to talk.

Stalin: About what?

Pasternak: About life and death…

At which point Stalin hangs up.

One hisses, the other mewls, one groans, the other weeps;

Кто свистит, кто мяучит, кто хнычет,

In Russian, literally, “one whistles, one meows, one snivels.” The Russia of 1933 has yet to witness the Moscow show trials, which began in 1936 and continued through 1939, during which the majority of the “scrawny-necked chieftains” would find themselves in the defendant’s box. Nor was the nation yet acquainted with the spectacle of self-incrimination by former Bolshevik leaders accused of every imaginable crime. Mandelstam’s description foresees the trials with prodigious exactitude: more than one of the defendants wept on hearing his sentence and fell to his knees to beg forgiveness from Stalin and the Party.

When Mandelstam is taken prisoner on the night of May 13, 1934, the NKVD does not yet have a definitive version of the poem. The presiding judge asks the poet to write out an authorized version of the poem for him and the poet obligingly does so. The first two lines read:

He wrote out the poem with the same pen the judge used to write the sentence that sealed his fate.

he prowls thunderously among them,

Он один лишь бабачит…

I translated the Russian babachit, a neologism, as “campea tonante” or “prowls thunderously.” Though previously nonexistent, the verb presents no difficulty to the Russian speaker because it is an onomatopoeia: ba-ba-chit,in other words, is to say “blah, blah, blah” in thunderous tones, to talk nonsense in the authoritative voice of the boss.

…showering them with scorn.

…и тычет,

Here, both the Spanish and the Russian reflect Stalin’s use of the familiar second-person pronoun, the Spanish tú, the Russian ty. A primary meaning of tykat (the verb meaning “to address someone as ty“) is also to point with a finger, to force something onto someone, to treat someone in an insolent and inconsiderate manner, and the word’s meaning moves between those usages. In Russia, it’s unusual for two strangers to use the familiar voice with each other; proper etiquette demands the most rigorous use of vy, the formal style of address, equivalent to the Spanish usted. The familiar voice is the prerogative of street sweepers and top bosses. During a sidewalk altercation, using ty is immediately perceived as a violent act of aggression. Mandelstam uses it here as an example of the abuse to which Stalin subjects his subordinates.

Forging decree after decree, like horseshoes,

Как одкову, кует за указом указ:

The word for decree here is ukase, widely used in the West, as well, to refer to an order that takes effect immediately and is without appeal. The image of decrees forged like horseshoes echoes a more quotidian Russian phrase, “to do something as if making blinis or blintzes,” in other words, rapidly and without thought, which amply conveys the banalization of the act of governing.

In 1929, Stalin believes that the moment has arrived to strip Russia of the useless appendix of capitalism. Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, the celebrated economist, theorizes about how to use the wealth the peasantry has undoubtedly accumulated during its years of greater freedom as a platform to launch the nation’s industrialization. But forced collectivization meets with generalized rejection, the peasantry fiercely resists, and Stalin launches a terror campaign. At least six million Ukrainian peasants die of hunger. The cities fill with fugitives who speak of the horror in hushed voices. By 1934, it is clear that the country is living under the tyranny of a police state compared to which the rule of the tsars seems benign and magnanimous.

he pitches one to the belly, another to the forehead,

a third to the eyebrow, a fourth in the eye.Кому в пах, кому в лоб, кому в бровь, кому в глаз.

However shoddy a dime-store emperor he may be, his decrees have fatal consequences: the banalization of government has become a banalization of death. The zoom-in by which the poet shows the parts of the body struck by the horseshoe/ukase resembles the close-ups in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, where an enormous pupil looms behind the lens of a pair of pince-nez, a mouth opens in a scream, the rictus of a face fills the whole screen.

Mandelstam, a poet of deep lyrical inspiration, would never have written poetry exalting the Revolution, unlike other poets of his time who passionately saluted the advent of October. Alexander Blok published a poem called “The Twelve,” which celebrates the revolutionary triumph in images replete with evangelical symbolism. Vladimir Mayakovsky believed the Revolution was the apotheosis of the futurist aesthetic that had given rise to the “loudmouthed bossman” persona he adopted in his elegy “At the Top of My Lungs.” It wouldn’t be long before Mayakovsky realized that in Stalin’s Russia there could be only one “thundering voice.” By the time destiny places him on a collision course with Stalin, Mandelstam has published a number of books, but not one of them is in a political register. They are books of such poetic value that all Russia—or at least that one percent that reads poetry—views him as a Master, with a capital M.

Every execution…

Что ни казнь у него…

In the mid-1970s, Lev Razgon, a gulag survivor and author of the implacable memoir Nepridumannoye (“Not made up,” translated in English as True Stories), is hospitalized in a Moscow clinic for a heart problem. A neighboring bed is occupied by a former Party official who is kind to the other patients and, in particular, to the writer, whom he cares for solicitously. Gradually he and Razgon come to be friends and the man ends up telling him about something he had never before confessed to anyone: his work as a member of one of the thousands of brigades of executioners that operated in the USSR during the 1930s. Razgon listens: the 100 grams of vodka the executioners drank at the beginning of each night, the trucks loaded with prisoners driven to outlying forests, the women sobbing at the edge of the pit, the cheers for the Party some of the men give, the shot to the back of the neck, the swift kick that sends the victim into the pit at the precise moment the trigger is pulled because the executioners’ wives are tired of laundering military jackets splashed with blood…

…is a carnival

—то малина

Literally: “is for him a raspberry,” a word with deep connotations of the criminal underworld. In Russian slang, malina (raspberry) refers to a criminal organization and the hideout from which crime lords carry out their schemes. Here, Mandelstam underscores the singular symbiosis between criminals and Bolsheviks, the impulse for vengeance and score-settling typical of the lumpen world the Bolsheviks allied themselves with. Every memoirist of the gulag mentions how the camps used common criminals against those incarcerated on the basis of Article 58—the “politicals,” accused of betraying the country. The common criminals did not participate in the original sin of being “class enemies” and therefore could be “reeducated”; they were assigned the easier service tasks as cooks, kitchen supervisors, or bathhouse workers—in Siberia, where heat, in and of itself, is a privilege.

that fills his broad Ossetian chest with delight.

И широкая грудь осетина.

In the original, the line begins: “And his broad chest…” Skinny, only 168 centimeters or five and a half feet tall, his face marked by smallpox, one arm half-paralyzed by polio, Stalin was a disappointment to people who had been expecting to meet with the colossus suggested by the supposed doppelgängers in granite and stone erected across the USSR. For Mandelstam, the broad chest that rejoices here is not a human chest but one made of iron. Inside, as if in the interior of a Minoan bronze bull, the millions of victims rage.

Was Iosif Dzhugashvili a Georgian or was he from Ossetia, the small Caucasian republic next door? Ossetians are deemed less refined and more violent; therefore Stalin was officially considered a Georgian. Curiously, the poem’s two final lines did not satisfy Mandelstam at all. It is astonishing that a fact as remote from politics as the verbal perfection of these final lines could occupy his mind during the suicidal sessions when he recited the poem aloud, but people remember him saying: “I should get rid of those lines, they’re no good. They sound like Tsvetáeva to me.” But there was no time for that, and the lines remained in the minds of those who heard the poem. Many years later when Vitaly Shentalinsky discovered the manuscript of the “Epigram Against Stalin” in the KGB archives, he found no variation at all from the samizdat version that had circulated across the USSR. The poem had etched itself faithfully in the memories of those who heard it recited in the distant year of 1934.

—Translated from the Spanish by Esther Allen

This Issue

June 10, 2010