Visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London who go in by the main Cromwell Road entrance and look up will see, suspended from the dome high overhead, a recently installed circular shelf of red lacquer, which holds 425 carefully arranged pieces of contemporary porcelain—plates, jars, bowls, cups, teapots—in a variety of subtle shades of white, cream, gray, light blue, and pale celadon. All the pieces in this installation are the creation of Edmund de Waal, perhaps the most eminent, and probably the most learned and articulate, British ceramicist working today—a man whose passionate desire to be a potter was first expressed at the age of five, when he insisted that his father take him to an adult evening class to be taught to make pots.

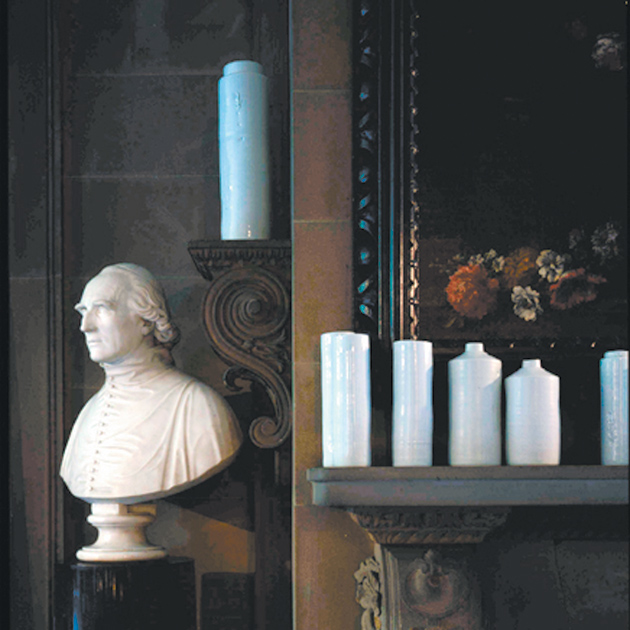

Celebrated for his ceramics of elegant simplicity, affecting purity, and ravishing glazes, in recent years de Waal has shifted his focus from individual pieces to installations of multiple works, such as those he has done for Lady Bessborough’s Artists’ House at Roche Court near Salisbury, for Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, for the Chapel Corridor at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, and for other locations. These installations consist of a number of pieces, whether bowls or brush holders, carefully arranged in sequences on a shelf or in a large open box divided into shelves hung on a wall. This latest work at the V&A, quite different from his earlier installations and his most ambitious to date, is said by the museum to be the largest installation commission in Britain by any single artist in a public or private space.1 In the unexpected book he has now written about his ancestors, The Hare with Amber Eyes, de Waal’s artistic sensibility and historical empathy are as animating as they are in his ceramic craft.

When I first went to England just after World War II, British pottery was still dominated by the messianic figure of Bernard Leach, and I retain a vivid memory of the surprise and admiration with which I first encountered his work in a Sussex drawing room in 1949. Leach was a dogmatic ideologue who championed the simplicity of Japanese ruralist pottery, claiming that his own pottery brought to the West the fundamental essence and mystery of the East. De Waal shares Leach’s devotion to Japan, which he first visited in 1981 at the age of seventeen in order to study the tea ceremony; he has also become adept in Japanese, which Leach was not.

Before going to Cambridge to study English literature, de Waal apprenticed himself to one of Leach’s devotees, Geoffrey Whiting. Later, however, in 1998, he published a book on Leach that achieved considerable notoriety for its severely revisionist reassessment of his work, pointing out that Leach’s “etiolated” experience of Japan and of Japanese pottery was actually very limited, confined to a small group of Anglophone potters and to a few types of pottery.

When de Waal returned to Japan in the early 1990s on a scholarship to study ceramics, he lived in Tokyo and there became affectionately acquainted with his great-uncle Ignace Ephrussi, a member of the immensely wealthy banking family, originally from Odessa, who had important banks in Vienna and Paris. Ignace, from the Viennese side of the family, had moved to Japan in 1947 after serving in the American army during the war. He lived with a Japanese companion, Jiro Sugiyama, whom he adopted as his son, and he was to die there in 1994, a few months after de Waal returned to England.

Uncle Iggie, as de Waal called him, had inherited a collection of the Japanese carvings called netsuke, which had originally been acquired by his ancestor Charles Ephrussi in Paris during the Belle Époque, when le japonisme was much in vogue. Usually carved in ivory, wood, teeth, or whale tusks, netsuke were originally devised as small toggles attached to the sashes of kimonos from which little purses or containers (sagemono) were hung; but as they developed as an art form netsuke gradually lost their utilitarian purpose. Rarely larger than two inches high, they tell stories or depict deities, famous people, craftsmen, animals, plants, etc., affording the artist opportunities for diminutive expressions of ingenuity, wit, or occasional eroticism (Shunga netsuke).

Edmund de Waal eventually inherited his Uncle Iggie’s collection of 264 netsuke, an inheritance that has occasioned his engaging book. An acutely responsive artist for whom objects have singular tactile, aesthetic, and historical importance, de Waal felt that possessing them conferred burdensome responsibility on him:

I realize how much I care about how this…losable object has survived. I need to find a way of unraveling its story. Owning this netsuke—inheriting them all—means I have been handed a responsibility to them and to the people who have owned them…. I want to know what the relationship has been between this wooden object…and where it has been. I want to be able to reach to the handle of the door and turn it and feel it open. I want to walk into each room where this object has lived, to feel the volume of the space, to know what pictures were on the walls, how the light fell from the window. And I want to know whose hands it has been in, and what they felt about it and thought about it—if they thought about it. I want to know what it has witnessed.

Improbable though it may seem that he should therefore abandon his artistic profession in order to fulfill this responsibility, he nonetheless left his studio and set out to revisit the places in Europe where those members of his Ephrussi family who have owned this collection of netsuke have lived. For the next couple of years de Waal spent most of his time attempting to rediscover and comprehend the vanished worlds of his forebears, and this book is the result of his quest.

Advertisement

The first, and unquestionably the most interesting, of these forebears is his second cousin once removed, Charles Ephrussi (1849–1905), who originally purchased the netsuke. Himself the affluent grandson of the patriarchal Charles Ephrussi from Odessa who established the immense family fortune by cornering the wheat market and who then, in Rothschild fashion, sent his two sons to establish banks, first in Vienna and then in Paris, young Charles Ephrussi arrived in 1871, aged twenty-two, at his family’s elegant mansion on the rue de Monceau at the very height of le japonisme: the term itself was coined by the drama critic Jules Claretie the following year, and in that same year Saint-Saëns’s brief opera about a woodblock print, La princesse jaune, was performed at the Opéra Comique.

Although foreign merchant ships had arrived in Japan around the middle of the century, it was only after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 that Japanese silks, fans, lacquers, bronzes, ivories, porcelains, scrolls, and ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”—those now-familiar woodblock prints by artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige that depict scenes from everyday life) began to flood the Parisian market. Already at the Exposition Universelle of 1867, however, objects sent from Japan had entranced visitors, and as early as 1856 Jacques Bracquemond had discovered an entire volume of Hokusai prints used as packing material in a shipment of porcelain. Six years before his death in 1867, Baudelaire claimed in a letter that he had acquired a lot of “japonneries,” and Whistler’s Princesse du Pays de la Porcelaine of 1864 already showed a Japanese screen, carpet, fans, and kimono.

These, however, were merely harbingers of the craze that was to follow the Exposition Universelle. Manet’s portrait of Zola, painted in 1867–1868, depicts a Japanese screen and a Japanese print by the artist Utagawa Kuniaki II on the wall behind him. Mallarmé, who championed his close friend in an essay in English entitled “The Impressionists and Édouard Manet” (1876) and whom Manet portrayed that same year smoking a cigar in front of a Japanese screen, was profoundly influenced by Japonism. (In the country house he leased in the forest of Fontainebleau, Mallarmé created a cabinet japonais in which to write, its walls hung with woodcut prints, its floors covered with tatami mats.) Also in 1876, Claude Monet painted the portrait, now in Boston, of his wife Camille in Japanese dress. Soon thereafter Proust’s Odette de Crécy had a Japanese lantern hanging from a silken cord in her entrance hallway and Japanese silk pillows embroidered with dragons scattered about her drawing room; her house was filled with “ses magots et ses potiches” (her Japanese figurines and vases), and she received Charles Swann robed in a kimono. When the couturier Paul Poiret opened his fashion house a year before the first performance of Madama Butterfly (1904), he created a sensation with his Confucius coat, cut like a kimono. (“Quelle horreur!” exclaimed the Russian Princess Bariatinsky. “When there are low fellows who run after our sledges and annoy us, we have their heads cut off, and we put them in sacks just like that!”)

Unlike chinoiserie, which had been so popular in the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but which was essentially decorative, imaginary, and superficial, japonisme’s influence on late-nineteenth-century painting was profound, giving Japan a much greater importance in the history of European art than China. Artists such as Manet, Degas, and Monet, and, slightly later, Gauguin, van Gogh, and Toulouse- Lautrec all strove to comprehend the basic artistic principles underlying Japanese art. As artists studied ukiyo-e, they became intrigued by such things as their characteristic asymmetry, their simplifications, their two-dimensionality, their areas of flat, bright color, and their shallow perspective. They also discovered the artistic value of what de Waal describes as “inconsequential gobbets of reality”—fragmentary, quotidian episodes of ordinary existence almost never depicted in the neoclassicism they were in rebellion against. In several of these respects, Daguerre’s new technique of photography was equally influential and must have seemed to underscore what the Parisian artists had learned from ukiyo-e.

Advertisement

Charles Ephrussi, as de Waal recounts, was a leading figure in the Paris art scene of his day, not only because he became editor of the influential Gazette des Beaux-Arts, but also because he assembled one of the early collections of Impressionist paintings. Most of the artists he collected—Pissarro, Manet, Degas, Sisley, Monet, Renoir, Morisot, Cassatt—were also personal friends of his. There is a well-known story about his purchase of Manet’s Bunch of Asparagus: Manet had asked 800 francs for it, but Charles was so delighted with the picture that he sent him 1,000 francs instead; Manet, in return, sent a small additional painting of one asparagus spear with an accompanying note that said, “This seems to have slipped from the bundle.”

It was Robert de Montesquiou who opined that Charles was the prototype for Proust’s Charles Swann—although most commentators think Swann is even more indebted to the Parisian dandy Charles Haas. Nevertheless, de Waal gives a convincing list of resemblances between his relative and Proust’s character. Charles was certainly a friend of Proust, and in an interesting fragment entitled “Un amateur de peinture—Monet, Sisley, Corot,” Proust explicitly acknowledges having seen in Charles Ephrussi’s collection some of the Monets he describes. The asparagus anecdote and Ephrussi’s appearance, incongruously garbed in a top hat, in Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party are both used by Proust to make fun of the Duc de Guermantes, who says of the latter that “il a l’air d’un petit notaire de province en goguette” and of the former, “Trois cents francs, une botte d’asperges! Un louis, voilà ce que ça vaut, même en primeurs!“2

Although he was an extravagant collector not only of paintings but also of Renaissance and eighteenth-century art and artifacts, what is surprising is that Charles doesn’t seem to have collected any Japanese objects more substantial than lacquer boxes (about which he wrote an article for the Gazette in 1878) and netsuke. He doesn’t appear to have been interested in systematically acquiring available Japanese objects of greater artistic importance, such as porcelains or bronzes, screens or scrolls. (Whether or not he collected ukiyo-e, which had such a decisive influence on the contemporary artists he so admired, is unclear. De Waal seems to assume that he did, yet I have found no evidence for it, and, interestingly, he does not appear in Ernest Chesneau’s list of major collectors of Japanese art in France.3)

One suspects that the netsuke may well have been somewhat less important to him than they have become for Edmund de Waal. To be sure, there was a certain vogue for collecting netsuke, notably shared by Edmond de Goncourt and Philippe Burty, each of whom possessed 140 pieces. But Charles Ephrussi did not actually collect them one by one, as he had collected Renaissance decorative art and was later to collect Impressionist paintings; he purchased his netsuke collection ready-made from the Parisian dealer Philippe Sichel. And when one of Charles’s cousins, Victor Ephrussi, with whom he had spent part of his childhood and of whom he was fond, married at the end of the century, Charles gave away his netsuke collection as a wedding present to Victor and his wife Emmy.

As the netsuke collection passes from Charles to Victor Ephrussi in 1899, we move in de Waal’s book from the dazzling sun-drenched Belle Époque world of the Impressionists in Paris to the more tenebrous Viennese world of Hofmannsthal and Schnitzler, Freud and Karl Kraus, Mahler and Hugo Wolf, Klimt and the Secessionists—a city aglow with the guttering candles of the Habsburg Empire. Victor Ephrussi was Edmund de Waal’s great-grandfather, and the second part of his quest takes him to the preposterously ostentatious, five-story Palais Ephrussi (plus a secret, windowless half-story inserted between two floors of the palace, which provided the living quarters of the servants) on the Ringstrasse across from the Votivkirche.

Judiciously using family diaries, photographs, oral reminiscences of his relatives, newspapers, and novels by Joseph Roth, for almost one hundred pages de Waal recreates with graphic skill the privileged fin-de-siècle lives his great-grandparents and his grandmother and her siblings led in Palais Ephrussi—the clothes they wore, the food they ate, the parties, concerts, and theaters they went to, their servants, his great-grandmother’s numerous lovers, his great-uncle’s scandalous elopement with his father’s Russian-Jewish mistress. Striving to recapture for us the ambiance of their existence, he gives vivid descriptions of the gilded interior of what he calls “the implacably marble Palais,” with its grandiose Nobelstock, the floor with the great reception rooms, which his great-grandmother said looked like the foyer of the Opera and refused to live in, preferring the only slightly less elegant floor above. He recounts the typical calendar of their year, with January spent on the French Riviera and April in Paris. In August they shared with their French cousins the Chalet Ephrussi in Switzerland, and September and October were spent at an Edenic family estate in Kövecses just across the Czech border, where Patrick Leigh Fermor, on his walk from Holland to Constantinople in the 1930s, later visited de Waal’s great-uncle Pips.

The vitrine with the netsuke collection was, surprisingly, not placed in one of the public rooms of the palais but in his great-grandmother’s very private dressing room. De Waal wonders whether this was out of embarrassment or affection, whether his great-grandmother didn’t want to have to explain them to her friends or whether she was so fond of them that she wanted them in her own intimate space. In any event, it was where Emmy Ephrussi’s small children (de Waal’s grandmother, her sister, and two brothers) came to visit their mother every evening as she dressed for dinner and where they were allowed to take the netsuke out of the vitrine and play with them. Often, she would invent stories for the children centered on one of the netsuke.

World War I, of course, brought an end to this world for everyone, but for the Viennese Ephrussis it also marked the beginning of disastrous financial decline. Victor’s bad Austrian investments, the punitive Versailles reparations, and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia all caused immense financial losses for his bank and for his family. There was also the swelling Austrian anti-Semitism to contend with. Earlier, in France, Charles Ephrussi had experienced the pervasive anti-Semitism of the Dreyfus affair as well as the nasty personal racism of people like Edmond de Goncourt; but the even viler, often physically abusive, anti-Semitism in nineteenth-century Vienna became more and more ominous as the twentieth century progressed.

The painful story of how the Ephrussis suffered after Hitler’s Anschluss in March 1938, how their Jewish friends fled or killed themselves or were sent to concentration camps, how the Palais Ephrussi was invaded by a mob and then occupied and stripped by the Gestapo, how Victor had to sign over all his personal possessions to the Nazis in order for him, Emmy, and his youngest son Rudolf to avoid being sent to Dachau, how he then had to sell the bank, at an absurd price, in order to have enough money for them to buy their way out of Austria, Rudolf going to America but Victor and Emmy getting only as far as Kövecses, where she committed suicide to escape the horror—the drama of this sordid saga is agonizingly retold by de Waal.

Eventually, just as World War II breaks out, Victor Ephrussi, de Waal’s grandparents, and their two boys, one of whom was de Waal’s father, all manage to get to Tunbridge Wells and begin a much-impoverished life in Britain. Victor, who in his last years would read Ovid’s Tristia with tears on his cheeks, died two months before Germany surrendered in May 1945; and in December 1945, his daughter Elisabeth (de Waal’s grandmother) returned to Vienna to see what if anything could be salvaged from Palais Ephrussi. It was then that she learned the remarkable story of how, at great personal risk, their faithful maid, Anna, had surreptitiously stolen the netsuke piece by piece in order, as she said, to save at least something for the family. While the Gestapo was focused on the grand objets d’art in the palace, Anna would sneak three or four of the tiny carvings into the pocket of her apron every time she passed the baroness’s dressing room and then hide them in her own mattress.

When Elisabeth arrived after the war, Anna proudly returned them to her, and she in turn brought them back to Kent and offered them to her brother Ignace. Iggie, just out of the American army, worked at that time for an international grain exporter, who posted him to Japan; thus he took the netsuke with him back to their country of origin in December 1947, almost a century after they had left. He and the netsuke were to remain there until his death in 1994. As de Waal’s book ends, he has taken the netsuke back to London, where his three small children arrange them in a new vitrine. Although he was never able to find out even the last name of Emmy’s devoted maid, his youngest child, born in 2002, is called Anna.

De Waal, who is uncommonly well read, has, not surprisingly, a special fondness for Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar,” which describes how a round pot, placed in the wilderness of Tennessee, confers by its very presence an order and a civilized refinement upon the chaotic, untrammeled world of nature around it. In a somewhat analogous way, temporal rather than spatial, his netsuke restored his family to him out of the chaos of history. His ancestral owners of the collection have all disappeared now, yet the artistic objects themselves have survived and retain the memory of his forebears, conferring an order and an existential significance on history. “How objects embody memory—or more particularly whether objects can hold memories—is a real question for me,” he has written.

Only someone for whom objects are as meaningful as they are for Edmund de Waal could have performed his quest. Only someone with his intelligence and sensitivity could have written such a fascinating account of his journey. The reader—and, indeed, the author—of this book will probably never fully understand the compulsion that drove him to undertake that journey, and his account inevitably leaves us with unanswered questions. Just why and how did a collection of netsuke impose, as he claims, a responsibility on him to explore his family’s history? Wasn’t it, rather, an opportunity that he may, consciously or unconsciously, have been seeking? But even if it was, how then did these Japanese artifacts allow him to open the doors of his family’s European past? Hasn’t his netsuke collection come to have greater significance for him than it did for any of its previous owners? Why did he feel compelled personally to revisit the rooms in Paris, Vienna, and Tokyo where the netsuke had resided? In short, how has a collection of tiny carvings exerted such irresistible exactions and provided such poignant ancestral awareness?

At the very end of the book, when his quest has taken him geographically and historically as far as Odessa and his family’s origins, he suddenly wonders what sort of book he is writing: “I no longer know if this book is about my family, or memory, or myself, or is still a book about small Japanese things.” The answer, of course, is that it is about all of those things, but most of all it is the evocative account of a gifted, interesting, inquiring man in search of his historic identity.

This Issue

October 14, 2010

-

1

For pictures of de Waal’s ceramics and the V&A installation, see his website at www.edmunddewaal.com.

↩ -

2

”He looks like a little provincial notary out on a spree” and “Three hundred francs for a bunch of asparagus! One louis, that’s all they’re worth, even when they’re out of season!”

↩ -

3

See the important two-part article on the Exposition Universelle by Chesneau, entitled “Le Japon à Paris,” in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1878, pp. 385ff. and 841ff.

↩