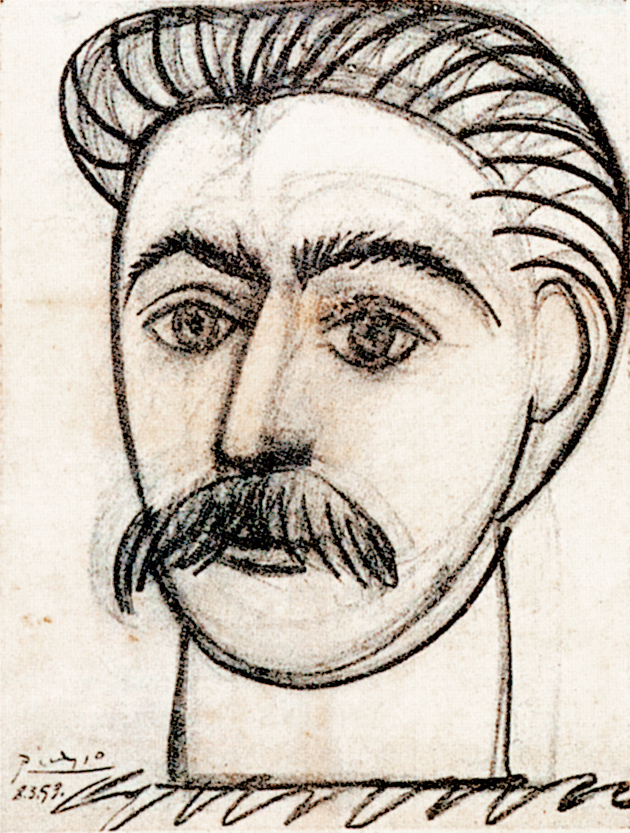

Musée Picasso, Paris/Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource

Pablo Picasso: Jeux de Pages, 1951. John Richardson writes that ‘that was how he saw war, Picasso told a group of friends in March 1959: medieval children playing nasty, medieval games.’ All images are © 2010 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Picasso’s work abounds in paradox, as did his religious and political beliefs, not to mention his love life. All the more reason to look skeptically at the exhibition “Picasso: Peace and Freedom,” which started out at the Tate Gallery’s Liverpool branch, is currently at the Albertina in Vienna, and will end up at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark. Lynda Morris, who has masterminded the show, makes much of the period following World War II when Picasso, who had joined the Communist Party in 1944, painted works that reflected Party propaganda. But as the art historian Gertje Utley has shown, many of the works in the exhibition, such as The Rape of the Sabines, are not “programmatic statements,” as the exhibition catalog claims, but testify to Picasso’s “life-long fear and horror of armed conflict.”1

“Picasso: Peace and Freedom,” in fact, includes a number of remarkable apolitical paintings, notably Picasso’s variations on works by Delacroix, Manet, and Velázquez that looked very much at home in Tate Liverpool’s refreshingly modest spaces, but their relevance to the show is spurious. Inevitably, “Picasso: Peace and Freedom” includes a lot of kitsch, including his doves, often displayed at Communist Party rallies. Unfortunately, Picasso’s ability to give kitsch a paradoxical edge was not in evidence at Liverpool, except insofar as his flocks of peace doves looked as out of date as the campaign they had once promoted.

The two wall panels depicting war and peace that Picasso painted in the Communist-inspired Chapel de la Guerre et la Paix in Vallauris, France, are far too large to travel. This is less of a loss than one might think. Wildly acclaimed in 1952, half a century later their simplistic sentimentality looks decidedly dated. The remarkable drawings for them in the show make up for them. Theoretically, the most important loan to the show, MoMA’s The Charnel House (1944–1945), is a sequel to Guernica in that it also portrays the mindless massacre of innocent people. Perhaps because the subject lacked the anguish and stimulus of a specific incident, The Charnel House fails to overwhelm. No wonder Picasso left it unfinished.

Unfortunately for students of agitprop, his only other major example of this genre, Massacre in Korea (January 1951), is conspicuously absent. Just as well; the painting’s crude imagery might have demonstrated that if Picasso’s psyche was not engaged, the message could work against him. Sadly, neither the exhibition nor the catalog includes a far more honest war painting done in the immediate aftermath of Massacre in Korea. Jeux de Pages depicts medieval page boys—their absurdly helmeted leader in spiky armor on a comically caparisoned horse—trying to look warlike. That was how he saw war, Picasso told a group of friends in March 1959: medieval children playing nasty, medieval games.

Compared to the new discoveries coming out of Spain and other European countries, Lynda Morris’s “rich variety of original and unknown material” is neither original nor unknown: pro-forma acknowledgments of charitable contributions to Party and other causes, long known to scholars such as Utley. Rather more worrying are the conclusions that Morris derives from these receipts. In a newspaper interview headlined “Picasso Revealed as a Feminist in New Exhibition,” she describes, for example, how a donation to the Women’s International Zionist Organization in Tel Aviv entitles us to see Picasso (famous for obliging his mistresses to read de Sade) as having “sympathy for women.” Contributions such as this confirm Picasso’s generosity to liberal causes. However, his art tells a somewhat different story. Take the painting Nude, Green Leaves and Bust, which sold for a record $106.5 million seventeen days before the opening of “Picasso: Peace and Freedom.” It depicts Picasso’s mistress in bondage and, according to the art historian Charles Stuckey, is based on one of Man Ray’s fetishistic photos. The image is redolent of predatory possessiveness. Picasso was indeed a paradox; he was also a misogynist.

As someone who frequently talked to Picasso in the 1950s, I realized that for all his overt loyalty to the French Communist Party, his most intense feelings in exile were more and more focused on Spain, specifically Spain’s “Golden Age” of Velázquez and Ribera, Góngora and Calderón. What Picasso wanted above all was a full-scale retrospective in his native land that would accord him a similar status. Hitherto this had been unthinkable. King Alphonso XIII had patronized Diaghilev’s ballet company and laughed at the comic horse in Parade at a 1918 performance in Madrid, but Spain made no attempt to honor its greatest artist until the Republican government took over. In November 1933, Ricardo de Orueta, a young Malagueño art historian newly appointed director general de bellas artes, was charged with contacting the artist. Since his Paris address was not known to the ministry, Orueta called the ambassador in Paris, the eminent historian Salvador de Madariaga. The conventional Madariaga replied that he had indeed met Picasso but had found him “arrogant and rude,” and the idea of a state-sponsored retrospective was “deplorable.”

Advertisement

Perturbed by Madariaga’s comment, Orueta took no further action. However, more progressive members of the government persisted and came up with a proposal. Unfortunately, so depleted were the new government’s funds that there was no money for shipping or insurance, and so no loans of paintings could be expected from foreign sources. All it could promise was a contingent of the Guardia Civil to escort the paintings from the French frontier to Madrid.

This lack of funds played into the hands of the newly created right-wing political organization the Falange and its charismatic leader, José Antonio Primo de Rivera (whose father had endeared himself to Picasso in 1917 by approving of his work). To give the Falange the cultural gloss that Marinetti’s futurists had supplied to Mussolini’s Fascist movement, Rivera—called “El Jefe”—had appointed as his cultural adviser the brilliant, fanatically right-wing Ernesto Giménez Caballero. Formerly editor of the country’s avant-garde La Gaceta Literaria, and a passionate aficionado whose concept of the corrida de toros as a mirror of Spain’s inherent theatricality rivaled Picasso’s, Caballero had transformed himself into the blackest of Catholic bigots. Still, his job was to inveigle prominent poets and painters, above all Federico García Lorca and Picasso, into the Falange. An easy conquest was Max Jacob. A former poète maudit who had converted to Catholicism (with Picasso as a godfather), this superb gay poet needed no coercion to join the Falange cause. Lorca would try to stay above politics and ended up murdered by the Fascists. When contacted by emissaries of Caballero, Picasso initially played it safe.

Aware that Spain’s greatest artist was taking his family on a bull-fighting tour in August 1934, Caballero invited him to a dinner in his honor in San Sebastián given by the Falange’s gastronomic society. Picasso accepted. During dinner, El Jefe proposed a retrospective exhibition in Madrid financed by the Falange. Besides providing a Guardia Civil escort for the works, they would cover the insurance. Thirty years later, to cover up his acceptance of Caballero’s invitation, Picasso told his Argentinean friend Roberto Otero that when Caballero likened his eyes to Mussolini’s, he had taken the next train back to Paris. Untrue. He and his family stayed on in San Sebastián for several days being entertained by the Falange. No wonder Caballero later boasted, to Picasso’s rage, that he had won him over.

Far from returning to Paris, Picasso ended up in Barcelona to attend the opening of the great new Museum of Catalan Art. He was anxious to see the stunning collection of Spanish art that had been acquired from the sugar king Luis Plandiura. The inclusion of nineteen of his early paintings delighted Picasso. This was the first time his work had been exhibited in a Spanish museum, let alone acquired by one. The experience made the prospect of a retrospective in Madrid even more of an idée fixe.

El Jefe’s grandiose offer of a retrospective failed to materialize. The Republicans soon outlawed the Falange and exiled General Franco to the Canary Isles. British secret agents masquerading as tourists (MI6’s code name: “Operation Miss Canary Islands”) quickly arranged for Franco to go to Morocco, and from there he launched the civil war.

The outbreak of war coincided with Picasso’s hate-filled separation from his neurasthenic Russian wife, Olga, which set off a major midlife crisis in the form of a temporary switch from painting to poetry. The war would also exacerbate Picasso’s fear of the French authorities. In their paranoia about Spanish anarchists, the police had always kept him under surveillance. Meanwhile, his mistress Marie-Thérèse’s pregnancy with his child had left Picasso accessible to other women, notably the strikingly intelligent Surrealist photographer Dora Maar, fluent in Spanish and formerly the mistress of the Sadeian writer Georges Bataille.

To help deal with his difficulties, Picasso called upon a friend since adolescence, a Catalan poet turned journalist, Jaime Sabartés, who had spent the previous thirty years editing and teaching in South America. They had remained in touch. Now in desperate need of support, Picasso summoned him back to Paris. He had never had a secretary; now he had one who was not only Spanish but was specifically Catalan in his canniness, discretion, and loyalty. Sabartés would be privy to all Picasso’s secrets.

Advertisement

One of Sabartés’s first tasks was to work on a smallish Picasso show with Paul Éluard, André Breton, Christian Zervos, and a Barcelona arts group, called ADLAN, so disparate that it included Lorca, Joan Miró, and Josep Lluis Sert, as well as Caballero. This opened in Barcelona on June 13, 1936—a few days before war broke out—in a gallery with an entry charge. Picasso stayed away. Left to Parisian intellectuals, the choice of works was too arcane for the public, and the best that could be said of it was that it was a succès de scandale. As a perceptive article on ADLAN said, the exhibition

included too many hermetic [i.e., cubist] works and monstrosities from the Dinard period of the late 1920s…when Picasso was getting back together with the surrealists. The show could be faulted for being too fragmentary and…for trying to legitimize avant-gardist activities…. “It did Picasso a disservice.”

Following the show, the envious Salvador Dalí dismissed Picasso, describing him as an express train that had arrived twenty years too late. What Barcelona—the city in which he grew up—needed instead was an exhibition that would chart the development of the artist’s seemingly disparate styles. The civil war would not put an end to his determination to have a full-scale retrospective in Spain.

Two months into the war, the Republicans appointed Picasso director of the Prado, albeit in absentia. Nevertheless, he took his duties very seriously, especially after the Condor Legion, which Hitler had put at Franco’s disposal, bombed the Prado and other Madrid targets. As director, Picasso was responsible for having the museum’s contents evacuated to Valencia. Two years later, when the treasures had to be transported for safekeeping to Geneva, Picasso personally provided the funds to rescue the seventy-five truckloads of paintings that, despite constant bombing and roads choked with refugees, had safely crossed the frontier into France. The only major victims were Goya’s Second and Third of May, severely damaged by a falling balcony, and the Spanish Republican guards, who were later handed over to the Germans by the French and sent to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

Musée Picasso, Paris/Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource

Pablo Picasso: Still Life with a Lamp, 1936. December 29, on the poster on the wall at left, was the date chosen by Louis Aragon for a demonstration celebrating Louis Delaprée, a columnist for the right-wing newspaper Paris-Soir who in his dispatches from the Spanish civil war was ‘merciless in denouncing atrocities, whoever committed them.’ He died on December 11, 1936, after his plane from Madrid to Paris was shot down over Spain by Soviet aircraft. According to John Richardson, his inclusion of the date indicates that ‘Picasso was one of Delaprée’s admirers,’ and the severed arm is his ‘first reference to the war.’

Paralleling the fighting in Spain was a war in the press. Atrocities by Republican extremists were denied by Europe’s Communist papers, while Franco’s use of Mussolini’s planes to bomb Palma de Mallorca was played down by conservative ones. There was, however, one formidably apolitical exception: Louis Delaprée, who wrote for the sleazy, right-wing Paris-Soir. Delaprée was merciless in denouncing atrocities, whoever committed them. This resulted in his ruthlessly honest reports being edited or turned down by his timid, rightist editors. Most of the paper’s available space was devoted to Mrs. Simpson, who was costing Edward VIII his crown. In his last dispatch from Madrid, Delaprée berated his editor for featuring the “putain royale” rather than the massacre of Spanish children.

Summoned back to Paris from Madrid, which was under Fascist siege, Delaprée left on a French embassy plane, which was shot down by Soviet aircraft while still over Spain. His injuries were not serious, but his treatment was botched and he died a few days later. Soviet fighter pilots had been instructed to kill his fellow passenger, a Red Cross official summoned to investigate the massacre of a group of Franco sympathizers by Republican extremists. Delaprée’s death devastated a widespread public that had read his haunting dispatches. Louis Aragon organized a demonstration in Delaprée’s honor and arranged the publication of his unexpurgated writings.

That Picasso was one of Delaprée’s admirers emerges in a seldom-exhibited anthropomorphic painting, Still Life with a Lamp. As so often, the artist portrays himself as a jug, and Marie-Thérèse—the mistress he was forsaking for Dora Maar—as a wretched-looking fruit dish. Linking them is a severed arm, Picasso’s first reference to the war, and one that would play a momentous role in Guernica. A poster on the wall consists of a date, “29 Decembre.” My collaborator, Gijs van Hensbergen, checked with Franco’s erudite biographer Paul Preston, who explained that December 29, 1936, was the day Aragon picked for his demonstration celebrating Delaprée. The announcement proclaimed: “The voice of a dead man denounces the lies of the press.”

In death, so his admirers hoped, Delaprée would awaken Europe to the anguish of war. Virginia Woolf, whose nephew Julian Bell had gone off to die fighting for the Republicans, had Delaprée’s reports on her desk when she was writing Three Guineas. Recently republished in Spanish under the title Morir en Madrid with a revelatory introduction by Martin Minchom, his texts are still terrifying.

There is no mention of Delaprée in the catalog of “Picasso: Peace and Freedom”; nor, rather more surprisingly, is there any reference to The Dream and Lie of Franco, Picasso’s two sheets of small engravings that rival Goya in their ribald mockery of war and Alfred Jarry in their mockery of Franco. The very same day he painted Still Life with a Lamp, he executed a disgustingly Jarryesque drawing of a Franco-like blimp figure seated at Olga Picasso’s cute, candle-lit piano, spreading its flippers across its seemingly shit-smeared keys. This was in fact Picasso’s first engagement in his conflict with Franco. Six months later he would embark on Guernica. Its imagery is redolent of Delaprée’s reports.

Asked where he stood politically in the years leading up to the Spanish civil war, Picasso would answer that since he was a Spaniard and Spain was a monarchy, he was a royalist. D.H. Kahnweiler, his dealer and close friend, and a lifelong socialist, asserted that Picasso was the most apolitical man he had ever met:

His Communism is quite unpolitical. He has never read a line of Karl Marx, nor of Engels of course. His Communism is sentimental…. He once said to me, “Pour moi, le Parti Communiste est le parti des pauvres.”

In the last months of World War II, this apolitical position was difficult to maintain. De Gaulle’s liberation of Paris had transformed the artist, albeit momentarily, into a Gaullist. But after dining with the general’s associates, he declared that they were “une bande de cons.” This perception made him, along with many of his fellow intellectuals, all the more susceptible to the Communists, whose party he joined in 1944. That Picasso’s private life was once again in a state of flux helped him to persuade himself that he was joining a kind of family. As a lifelong pacifist, he also persuaded himself that he had joined the party of peace—an alternative to the Catholic faith that he had tried and failed to repudiate and seemingly drew on throughout his life.

Over the next eight years, Picasso and Françoise Gilot, who would bear him two children, lived in Vallauris, a dilapidated Communist-run pottery-making town near Cannes, which the artist would transform into a thriving ville d’art. Besides reinventing the craft of ceramics and transforming it into a modern art form, he would demonstrate that he had the people’s interests at heart by allowing inexpensive copies to be made; he would also revolutionize printmaking techniques, which he hoped would bring his work within the reach of the workers he identified with. In fact, the low-priced masterpieces that poured from his presses too often wound up making fortunes for art dealers.

In no time, Picasso became celebrated, along with Louis Aragon and Frédéric Joliot-Curie, as one of the Communist Party’s Three Musketeers. Much as he loathed foreign travel and public appearances, he allowed himself to be trotted out as a figurehead at peace conferences in Sheffield, Rome, and Wrocław. At the same time, he made no secret of his distaste for Marxist theory and factional squabbling. Paradox kept him balanced, he once said. When Aragon chose his lithograph of a dove as the Party’s emblem of world peace, Picasso could not resist pointing out that he kept these vicious birds in separate cages, otherwise they would peck each other to bits. Still, he named his daughter Paloma after them.

Although he had turned a blind eye, like Sartre and Beauvoir and many other French intellectuals, to Soviet brutality in Eastern Europe, Picasso’s faith in communism had already begun to falter when, in March 1953, Aragon commissioned him to do a portrait in commemoration of Stalin’s death for Les Lettres Françaises, the Party’s literary journal. Aragon was blamed when Picasso’s stylized rather than idealized image of a heroic, overly mustachioed young leader was received with howls of derision by Party members when it was published. This was not how true believers envisioned the “eternal father of the people.” After this episode, Picasso limited his agitprop contributions to Party fluff.

When the woman in Picasso’s life changed, everything else changed, including his political attitudes. Françoise Gilot was a left-wing intellectual, but his next companion, Jacqueline Roque, had no time for communism. Neither did Jean Cocteau, who had recently reclaimed the position of jester in Picasso’s court. Characteristically, the artist would sometimes agree with him: “Like most families, the Communist Party is full of shit.” If, however, Cocteau dared to take a similar line, the artist would become defensive and berate him.

The ruthlessness with which the Soviets crushed the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 and the French Communist Party’s condoning of this abuse of human rights provoked a far deeper disillusion. Given his much-publicized identification with the Party, and unable to face the consequences of being a turncoat, this most ironical of men found himself at an almost total loss. “Il était coincé,” Jacqueline later said. To friends he would raise his eyes to heaven, extend his hands, and shrug his shoulders in despair at Soviet excesses.

In late 1956, Picasso asked the collector Douglas Cooper and me to intervene and stop James Lord—an American writer the artist had befriended in 1944 and dubbed “mon GI”—from publishing an open letter challenging him to publicly condemn the Soviet brutality. “A crass attempt to get his name in the papers at my expense,” Picasso told us. It would, he said, endanger his own “delicate negotiations” with the Party. Directives from his Communist minders would have been more accurate. In letters described by Gertje Utley as “Machiavellian in their manipulative use of information,” Hélène Parmelin, the fanatically pro-Soviet and Russian-born friend of Picasso, was doing her best to prevent him from joining the powerful intellectuals, including Sartre and Leiris, who were then criticizing Russian aggression. Parmelin’s directives worked: the letter of protest that Picasso and some of his associates published in Le Monde was shamefully weak. The ultimate irony: students in Warsaw used a mock-up of Picasso’s Massacre in Korea for an anti-Soviet protest.

Picasso surely knew that Parmelin was working on the Soviets’ behalf, but he did not fully realize that there were friends with very different sympathies in his entourage. Following the invasion of Hungary, the artist’s favorite photographer, an intrepid midwesterner, David Douglas Duncan, reported to Richard Nixon (then vice-president): “Look, amigo, I know this man very, very well…. If officially invited to visit the United States…I feel certain he’d come…. That would be a cultural body-blow to the Communists.” Nixon duly replied: Picasso would be granted a tourist visa, but no official invitation. He never visited the US.

Rather more surprising is the identity of Franco’s representative in Picasso’s entourage: Luis Miguel Dominguín, the suave Madrileño bullfighter who can be identified as the torero in so many of Picasso’s tauromachic images. The artist had once tried to buy the Vallauris soccer field and turn it into a bullring for Dominguín to star in. Back in Spain, Dominguín was a regular guest at Franco’s partridge shoots and often consulted by his hosts, for example, about rumors that Picasso would hand over his works to Mexico and about how he could be stopped if the rumors were true. Franco and his associates tried, through Dominguín, to bring pressure on Picasso to cooperate with the regime.

More to the point, the worldwide power of the anti-fascist icon Guernica, which had been left in the custody of MoMA, had become a crucial problem. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs had been inundated with complaints from ambassadors in key capitals that this painting generated anti-Franco feeling wherever it was shown. How could they exorcise it? Twenty years earlier, the Falange’s offer of a retrospective in Madrid had nearly won Picasso over. Why not bait their hook with the same lure? He might even include Guernica in the show. Dominguín’s reports to Franco are likely to have suggested this course of action. In 1956 a young employee at the Institute of Spanish Culture, Moreno Galvan, was dispatched to Cannes to ask whether Picasso would allow Madrid’s Museum of Contemporary Art to follow MoMA’s example and celebrate his seventy-fifth birthday with a retrospective later that year.

At first, Picasso refused to receive Galvan, but after a month he saw him and Galvan conveyed the museum’s request. Galvan was anything but a Francoist and had no visible ties to the regime—although Franco’s officials would have known of his mission. Picasso neither turned his proposal down nor accepted it. Convinced that diplomacy was called for, the foreign minister asked Jose Luis Messia, cultural attaché in Paris, to take over the negotiations from Galvan. The wily Messia demurred; the Franco government should not show its hand. The director of the Contemporary Museum in Barcelona should be put in charge—so long as he did the minister’s bidding. This plot would not have come to light if the art historian Genoveva Tusell had not discovered the documents confirming it while working in the ministry’s archives. In a letter to Galvan, the cultural attaché wrote: “Imagine if García Lorca was still alive, we could kill off two myths at the same time.”

Musée Picasso, Barcelona/Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource

Pablo Picasso: Las Meninas, after Velázquez, No. 1, 1957. John Richardson writes:

‘One of the most subversive Las Meninas jokes was Picasso’s addition of Dalí’s signature mustache to Velázquez’s face in the first and most elaborate of his variations.’

Despite the ministry’s insistence on secrecy, rumors spread that Picasso had promised Madrid not only a full-scale retrospective but a donation of thirty major works. Cocteau’s diary mentions a letter Picasso received from Spanish “noblemen” begging him to abandon the idea. A message from Picasso to his banker, Max Pellequer, suggests that he was blowing hot and cold. In the end, the artist concluded that a Franco-backed exhibition would shatter his image and amount to a victory for fascism.

A gossipy Madrid paper, Informaciones, broke the story on April 10, 1957. Although picked up in the foreign press, the news soon evaporated, never to be resuscitated. The Spanish government denied any involvement in the project. Picasso chose to forget all about it. For the sake of appearances, he continued to come up with obligatory peace doves and receive official visits from the French Communist Party leader Maurice Thorez, though after Budapest, he would be a Communist in name only. But he never publicly or formally resigned from the Party.

That Picasso’s feelings for communism had a counterpart in his feelings for Catholicism emerges in a statement to his dealer, Kahnweiler:

My family…they have always been Catholics. They didn’t like the priests and they didn’t go to mass, but they were Catholics. Well, I am a Communist and I….

Meanwhile, according to Jacqueline, Picasso was secretly making charitable donations to Catholic causes. He was also corresponding with a Spanish priest who wanted him to fresco his village church. Deny it though he might, he was, according to Jacqueline, “plus Catholique que le Pape.”

Now that his prospect of a Spanish retrospective had vanished, Picasso decided to paint himself into Spain’s Golden Age using Velázquez’s Las Meninas as a medium. In the summer of 1957, he embarked on a radical deconstruction of this most challenging of masterpieces. The variations resulting from this five-month-long, no-holds-barred battle between the greatest artist of Spanish history and the greatest artist of modern times are the prelude to the Baroque Mosqueteros paintings of his last decade, in which he recaptures the low-life and raffish theatricality of Roja’s great fifteenth-century novel La Celestina and the plays of Lope de Vega.

One of the most subversive Las Meninas jokes was Picasso’s addition of Dalí’s signature mustache to Velázquez’s face in the first and most elaborate of his variations. Although Dalí’s antics once had amused him—Catalans could do no wrong—Picasso proceeded to drop him for announcing to the press that besides having the bishop of Barcelona offer up a Mass for his soul, he was chartering a submarine to kidnap Picasso and take him back to Spain.

Unlike Picasso’s variations on Delacroix and Manet, which Kahnweiler had shown, split up, and sold, the Las Meninas variations were, Picasso decided, to be kept off the market. They were all destined for Spain. With Picasso’s approval, Sabartés had secretly embarked on negotiations with the Catalan government to establish a Museu Picasso in Barcelona. Although there was no visible encouragement from official Madrid, the museum would open in 1963, twelve years before Franco died. The Velázquez paintings were among Picasso’s first donations. Francoist authorities tried to make the museum almost impossible to find: it was officially listed as the Fundación Sabartés. Today, as the Museu Picasso, it is on the way to becoming a Picasso research center with a major repository for a mass of early documentation and the new material about Picasso’s involvement in Spain that is coming to light.

This Issue

November 25, 2010

-

*

See her Picasso: The Communist Years (Yale University Press, 2000) and “Picasso’s Politics,” her recent letter to The Burlington Magazine, September 2010. ↩