In response to:

Can We Create a National Digital Library? from the October 28, 2010 issue

To the Editors:

In your October 28 issue, Robert Darnton makes a plea for a national digital library [“Can We Create a National Digital Library?”]. I endorse this. We in the New Zealand Society of Authors have made a similar plea to our own government although to date this has fallen on deaf ears. But Mr. Darnton does himself no favors by declining to raise what he describes as “the vexed question of copyright.” This is the elephant in the room that is going to bedevil any such proposal anywhere until it is resolved. There is no point in professional writers, i.e., those who seek to earn their living by their writing, putting fingers to keyboard if they are not going to be paid for their efforts. How precisely does Mr. Darnton propose to resolve that conundrum?

It is for this reason that the NZSA is implacably opposed to the Google book project in its current form. We consider that the digitizing of books without the specific consent of the author is theft of our intellectual property. It is extremely galling to spend two years writing a book only to find it popping up on someone’s database and to have them selling a right of access to it or otherwise capitalizing on it but the writer receiving not a cent by way of this use of our copyright. I would be delighted to have my books digitzed and available to the whole world. But who is going to pay me for the work I have put into them?

Tony Simpson

President

New Zealand Society of Authors

Wellington, New Zealand

Robert Darnton replies:

If I could unvex the question of copyright, I would gladly do so, but heads wiser than mine have beaten themselves against it, to no avail. Nonetheless, I can assure Tony Simpson that the National Digital Library I propose would not violate copyright. It would be built incrementally, beginning with the digital files of books in the public domain, about two million works. To them, one could add all noncopyrighted material digitized from the special collections of libraries and museums.

Further ingredients could come from collections that have already been aggregated from networks of databases such as the National Digital Newspaper Program, Digital Collections and Content, Opening History, the National Science Digital Library, and the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Taken together, these sources represent many millions of items, and they might be supplemented by the still larger holdings of HathiTrust, the Internet Archive, and PublicResource.Org.

Of course, permissions would have to be granted, platforms coordinated, and the architecture carefully designed; but those building blocks could form the foundation of a digital library greater than anything that exists today—all of it constructed from material that is not covered by copyright. If Congress passed legislation that would make available orphan works—for which the copyright holders have not been located—a second tier could be added from the enormous corpus of books published between 1923 and 1964, a period of great uncertainty in copyright.

A third tier could be constructed from books that are covered by copyright but are out of print. Permission would have to be secured from the copyright owners, but many authors of books that had long ago ceased to sell would be delighted to have their works revived in digital form. How they would be compensated and whether a “digital lending” or other mechanism could be devised to protect the interests of rightsholders while facilitating use of copyrighted materials from the library are among the questions that still need to be addressed.

If the terms were attractive enough, publishers might make their backlists available. Little by little, the edifice would incorporate most of the literature from the twentieth century; and as the years went by, it would continue to grow, without interfering with the commercial market for currently available books. It would include works from many other media, always with respect for the rights of their creators. And when it reached its full height, it would tower over all previous attempts to make the record of human experience available to all of humanity.

I say “humanity,” because some readers objected to my use of “cultural patrimony.” Others disliked the name I used in my article, “National Digital Library,” because they took it to imply that the library would contain nothing but native products duly certified as made in America. America, however, is a country of immigrants, who brought their cultural baggage with them. A national American library must therefore be international, composed of works in a multitude of languages.

To avoid misunderstanding, I would be happy to drop “National Digital Library” in favor of “Digital Public Library of America,” the name preferred by most of those who attended the workshop that met at Harvard on October 1–2 in order to discuss the possibility of creating such a thing. “Public” suggests the country’s rich heritage of local libraries—“free to all,” as proclaimed by the inscription over the main door to the Boston Public Library. A Digital Public Library of America—which might draw on the holdings of the Library of Congress—would connect those municipal libraries to the greatest collection ever assembled of books and other materials. It would also be an asset to community colleges—not “junior” colleges, another term I am sorry to have used—and educational institutions of all kinds, including those at the K–12 level. If we want to promote education, we should create a digital library linked to every classroom in the country.

Advertisement

It remains for me to repair one other misconception. Although I convened the workshop, I merely provided an occasion to launch a debate involving many people who do not necessarily share my ideas. My New York Review article was drawn from the talk I gave at its opening and represents my views, not those of the others, and it should not be taken as a report on the discussions that subsequently took place. Those discussions will lead to other meetings involving our wider community, which in turn may open the way to the creation of a great digital library. If they do, the edifice cannot be constructed without a broad debate on a national scale, for the library will belong to the American people, and the people themselves should have a voice in its design.

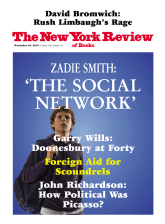

This Issue

November 25, 2010