Apart from the deaths of young men there is little meaning in the fighting, suffering, heroism, and occasional criminal behavior in Matterhorn, a novel about a company of Marines fighting in Vietnam in 1969. For them, concludes Karl Marlantes, death was “the only real god they knew.” There is friendship and sacrifice among these men, usually with the white Marines in one group, the black ones in another. The Americans see Saigon’s soldiers and officials as corrupt, useless, or cowardly; “Nagoolians,” the Marines’ term for their adversaries, are thought to be brave and able to keep on fighting. The Vietcong or National Liberation Front is only rarely named as such in the book. Nor are Vietnamese civilians. The Marines understand that when the war is over they will go home and the North Vietnamese will remain.

Karl Marlantes, a much-decorated Marine veteran of Vietnam, originally wrote a book of over 1,600 pages; now, at almost six hundred pages, it is still very long and sometimes awkwardly written. I recently heard him say during a BBC interview that Matterhorn’s central character, Lieutenant Waino Mellas, is based on his older brother and another friend. But he also emphasized that Mellas’s experiences in the novel were his own or ones he had heard about.

Like Marlantes, Mellas grew up in a small town and went to an Ivy League university. The Marines tease him about this and although he is keen to win a medal and get his name in the papers he feels so frightened in battle that he considers running away. But after a few months he gains some respect from his men and feels like one of them. After being wounded he returns to Bravo Company and, at the end of the book, he is about to set off on another bloody mission.

As usual, the Marines are at the mercy of the ambitious colonels and generals ordering them into one more assault on the mile-high Matterhorn, only four kilometers from the border with North Vietnam. The Marines named such peaks after Swiss mountains. Mellas’s men had already taken the Matterhorn under heavy North Vietnamese fire, only to be ordered to leave it. Now they must retake it from defenders firing downhill from almost impregnable bunkers and “fighting holes” that the Marines themselves had constructed when they had occupied the mountain.

Marlantes’s descriptions of battle are sometimes telling, although not more so than those in many other novels from the nineteenth century to Vietnam. Running and crawling, Mellas’s men

took approximately five seconds to cross that deadly ground. In that time, one-third of the remaining thirty-four in the platoon went down.

Then attackers and defenders joined together and bellowing, frightened, maddened kids—firing, clubbing, and kicking—tried to end the madness by means of more madness.

Vancouver, the bravest Marine in the company, already wounded and brandishing a captured sword, hacks down two North Vietnamese soldiers before he is mortally shot:

One of the two NVA [North Vietnamese Army] soldiers whom Vancouver had attacked cried weakly for help. Vancouver, his face in the mud, heard him and knew they would die together.

Those convincing sentences are followed by a hollow comment that should have been cut: “That felt appropriate somehow.”

Similarly there is a persuasive description of exhausted Marines climbing a cliff, roped together, and in danger of either being shot or falling off. Two of the Marines, exhausted and frightened, “were crying openly….” Then, quite inappropriately, Marlantes adds: “like small children who needed to be fed and tucked into bed.”

Some passages suffer from no such weakness: the Marines

pulled ponchos off the dead Marines’ belts, which were still attached to their pulped torsos, to provide body sacks. They had no idea if the correct body parts would make it home to the correct wives or parents. The best they could do was, put together one head, two arms, and two legs.

At the end of another battle,

the day was spent in weary stupefaction, hauling dead American teenagers to a stack beside the landing zone and dead Vietnamese teenagers to the garbage pit down the side of the north face.

Mellas knows

with utter certainty, that the North Vietnamese would never quit. They would continue the war until they were annihilated, and he did not have the will to do what that would require.

And then another hollow sentence: “He stood there, looking at the waste.”

Behind the killing lie the ambitions of the senior officers. Snug, clean, drinking heavily, and deeply cynical, they drive Mellas’s Marines into increasingly dangerous situations, the colonels shouting their demands and threats down the radio to junior officers under heavy fire who are watching their men die. The most interesting character in the book is Bravo Company’s executive officer, Lieutenant Hawke, eventually killed by black soldiers who “frag” him—blow him up in his tent—after mistaking him for another man. Hawke explains ambition to Mellas:

Advertisement

The point is the colonel’s been passed over for bird colonel [the next senior rank] once already. This battalion is his last fucking chance. If he doesn’t make it, it’ll be Bravo Company’s fault…. He isn’t above making a few sacrifices to further his career either. And no I don’t mean personal sacrifices….You guys are going to make or break his career as far as he’s concerned.

Body counts, not ground occupied, become the goal. Mellas reports to his commanders that his Marines have killed one “probable,” an enemy soldier whose body they didn’t see but may have been shot. But

the records had to show two dead NVA. So they did. But at regiment it looked odd—two kills with no probables. So a probable got added…. With the way the NVA pulled out bodies, you had to have some probables…. Four confirmed, two probables…. By the time it reached Saigon, however, the two probables had been made confirms, but it didn’t make sense to have six confirmed kills without probables. So four of those got added. Now it looked right. Ten dead NVA and no one hurt on our side. A pretty good day’s work.

“What was the military objective, anyway?” a colonel wonders. “If they were here to fight communists, why in hell wasn’t Hanoi the objective?… The Marines seemed to be killing people with no objective beyond the killing itself.” Mellas comes to enjoy killing and nearly shoots the officer who had ordered Bravo Company into a meaningless bloody action. Down in the lowest ranks, a Marine, Hippy, asks Mellas:

“Tell me something, Lieutenant…Just tell me where the gold is.”

“Gold?” Mellas looked puzzled…. Hippy was struggling with something deep….

“Yes, the gold, the fucking gold, or the oil, or uranium. Something. Jesus Christ, something out there for us to be here. Just anything, then I’d understand it. Just some fucking gold so it all made sense.

Mellas didn’t answer…. “I don’t know,” he finally said. “I wish I did.”

As it happens these last words were the very ones ex–Secretary of State Dean Rusk used when his son asked him what the war was for.

In his BBC interview, Marlantes observed that in Vietnam he “didn’t know anything” about the black Marines who play a big part in his novel. Most are brave in the heat of battle; with one or two exceptions they despise whites, and they speak in an argot that Marlantes must have at least partly invented since he conceded he had little to do with them. They, too, try to understand the war, which, one explains, is

against brown people…. The draft is white people sending black people to fight yellow people to protect the country they stole from red people. No black man should be forced to defend a racist government. That be Article Six of the Black Panther Ten-Point Program.

Although, as he later made clear, he heard no such conversations, Marlantes then introduces a black Marine who reminds the racist one that the real hero is

that little girl go to school in Little Rock, wear a nice dress, scared shitless. She don’t pack no heat [weapon], but that picture a her walkin’ to school between federal marshals turned hearts. It those college boys gettin’ murdered for registerin’ voters. Yeah, white college boys.

I have written several times in these pages that the victorious North Vietnamese are a paradox. In Matterhorn they fight hard, are disciplined, and show little fear. But in the novel The Sorrow of War (1993), by the North Vietnamese writer Bao Ninh, when the war they have won is almost over, in 1974, the North Vietnamese soldiers sing:

Oh, this is war without end,

War without end.

Tomorrow or today,

Today or tomorrow.

Tell me my fate,

When will I die.

Bao Ninh, himself a soldier, wrote:

Victory after victory, withdrawal after withdrawal. The path of war seemed endless, desperate and leading nowhere…. The soldiers waited in fear, hoping they would not be ordered in as support forces, to hurl themselves into the arena to almost certain death.

In Novel Without a Name (1995), by Duong Thu Huong, also a North Vietnamese veteran, one of her characters condemns the military higher-ups:

We country folk have gagged ourselves, our stomachs and our mouths, even our penises. But when it comes to the generals, they know how to take advantage of a situation. Wherever they go…they make sure they have plenty of women. In the old days they had concubines; now they call them “mission comrades.” …For so long, it’s just been misery, suffering, and more suffering…. How many lives were sacrificed to gain independence? The colonialists had only just left Vietnamese soil and these little yellow despots already had a foothold.

Later, two high North Vietnamese officials discuss the pleasures of power:

Advertisement

All you need to do is mount a podium perched above a sea of rippling banners. Bayonets sparkling around you. Cannons booming. Now that’s the ultimate gratification: the gratification of power. Money. Love.

Matterhorn is very violent, with its casualties like the Marine whose feet are blown off and another in agony because a leech has entered his penis. Such scenes take up many pages. The BBC interviewer asked Marlantes about a critic who accused the novel of being so violent that it was a form of wartime pornography. Marlantes brushed this aside by asking if the same would be asked of Tolstoy. If he meant War and Peace or Caucasian short stories such as “Hadji Murat,” this is a ludicrous comparison. The battle scenes in War and Peace are pointedly about how Pierre, André, and the cavalrymen react to battle. Pierre at the Battle of Borodino:

Suddenly a terrible shock threw him backwards onto the ground. At the same instant the flash of a big fire lit him up, and at the same instant a deafening roar, crash, and whistling rang in his ears.

When he came to, Pierre was sitting on his behind, his hands propped on the ground; the caisson he had been closest to was not there; only charred green boards and rags lay about on the scorched grass, and a horse dragging broken shafts trotted past him, while another, just like Pierre himself, lay on the ground and shrieked long and piercingly.

In Matterhorn we don’t come to the inner life of the Marines simply from their actions or speech. We are left with flat attempts to describe their thoughts. One can almost see a comic-book character with the word “Thinks” in a balloon over his head. Mellas says:

The things he’d wanted before—power, prestige—now seemed empty, and their pursuit endless. What he did and thought in the present would give him the answer, so he would not look for answers in the past or future. Painful events would always be painful…. The jungle and death were the only clean things in the war.

Karl Marlantes recently told a London newspaper that years after he returned from Vietnam,

he walked into a boardroom in Singapore and saw a pile of corpses on the table. He became terrified in lifts, the noise their doors made was like the sound of a helicopter tailgate opening. In bed one night he heard a sound and rushed out naked in the street, ready to fight and kill. In his car he heard a man honk his horn, he leapt out, flung himself on the man’s bonnet and started kicking in his windscreen—“I wanted to kill him.”

In Vietnam, after the first few weeks, you knew that any sound or movement in the jungle was the enemy and you fired at once. Marlantes was reverting to a more primitive state, to the “monkey madness” of the soldier in the lethal jungle.

He described these symptoms to a man during a “mental-health week” in Santa Barbara. The man suddenly asked, “Have you been in a war?”

I broke down, bawling, snot pouring out of my nose—it went on for fifteen or twenty minutes, my ribs were sore for three days. The whole room was looking at this guy falling apart. He told me I had post-traumatic stress disorder, and he made me walk straight out of the building and go eight blocks to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. That’s when I started to get healed.

In one of Matterhorn’s few memorable passages, a Navy nurse looking after the nearly blinded Mellas on a hospital ship tells him:

“You’ve got to understand what we do here…. We fix weapons.” She shrugged. “Right now you’re a broken guidance system for forty rifles, three machine guns, a bunch of mortars, several artillery batteries, three calibers of naval guns, and four kinds of attack aircraft. Our job is to get you fixed and back in action as fast as we can.”

Whether a Navy nurse would ever have said such things to a wounded Marine, at that moment Matterhorn came to life. It helps explain what happened to Marlantes in the years after he came home wearing his sixteen medals.

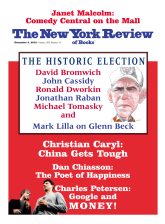

This Issue

December 9, 2010