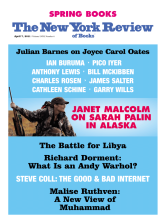

William Parry

Graffiti art by Banksy on the Palestinian side of Israel’s separation wall, in the East Jerusalem district of ar-Ram; photograph by William Parry, whose book Against the Wall: The Art of Resistance in Palestine will be published in the US by Lawrence Hill Books/Chicago Review Press this spring

1.

The announcement appeared on a Japanese website: the first sushi restaurant had just been opened in Ramallah. I immediately thought of the Palestinian prime minister, Salam Fayyad, and his policy for the West Bank. With the peace talks going nowhere, why not create the modern trappings of a real country that one day could become a real state? New roads, banks, “five-star” hotels, office towers, condominiums. He calls it “ending the occupation, despite the occupation.”

A visitor to Ramallah is immediately struck by the cranes and scaffolding of fresh construction. That and the Palestinian gendarmerie in red or green berets patrolling the streets, young men trained and equipped largely with US money, and overseen first by US Lieutenant General Keith Dayton and since last October by Lieutenant General Michael Moller.

This is the new Palestine, collaborating with Israel and the US to smarten up the West Bank and keep down Hamas, even though Prime Minister Fayyad was never elected, and Hamas won the last Palestinian elections in 2006. Under President Mahmoud Abbas, and his prime minister, the West Bank is supposed to outdo Islamist Gaza in prosperity and security. The Soho Sushi and Seafood Restaurant had to be linked to this enterprise.

Located inside the Caesar Hotel, a modern building in a plush Ramallah suburb, the Soho restaurant was empty when we arrived for lunch. Like the mausoleum of Yasser Arafat, erected in polished Jerusalem stone on the ruins of his old headquarters—shot to pieces by the Israeli army during the last years of his life—everything looked brand new, shiny, still unused. Phil Collins was singing softly in the background. A friendly waitress with long curly dark hair and black pants took our orders for sushi rolls. Her name was Amira; she was a Christian Palestinian from Bethlehem.

Amira explained that the seven Palestinian sushi chefs employed by the hotel had been trained by a Japanese lady from Tel Aviv. They had had to learn how to make sushi in two months. The result, so far, was mixed. Business was picking up, Amira said. But there was a slight drawback. The Jordanian man who sold the land to the Palestinian owners of the Caesar Hotel had stipulated that alcohol may not be served on the premises.

Although she had never been to the US, Amira carried an American passport, as well as Palestinian identity papers. Her parents had become US citizens before returning to Palestine, where her father taught Arab literature in Bethlehem. This was her home, Amira said, in perfect English. She explained that she had been trained in restaurant management in Spain, in the Basque country. The Spanish, she found, were confounded by her, since they expected all Arab women to wear a veil. When she went to parties, she said, it was always the same story:

A Spanish guy would ask where I was from. When I said I was from Palestine, he would give me a long lecture about how horrible the Israelis were. Then he’d turn round and leave me stuck on my own. You see, they think we’re all terrorists. It’s very sad.

She repeated this phrase a lot, Amira. It was very sad, for example, that it could take three, four, even five hours to get to Bethlehem from Ramallah, depending on the Israeli checkpoints. Normally the trip would only take thirty minutes, via Jerusalem. But Ramallah is surrounded now by Israeli settlements. And these are connected by a network of roads only Israelis are allowed to use. Ramallah is also cut off by the high concrete wall that divides Israel from Palestine. Israelis are not permitted to visit Ramallah, or Bethlehem. Some Palestinians have permits to go to Jerusalem. Some live there. But it can take them three, four, or five hours to get there, even though the trip can be made in fifteen minutes by car.

Amira also told me how hard it was for young Palestinians to find jobs on the West Bank, despite the new polish given to Ramallah, and how difficult it was to make ends meet, even if they did manage to be employed. A great deal of money keeps pouring into Palestine, from the US, the European Union, the Gulf states, and other Arab countries, to build hospitals, roads, hotels, and so on, but the territory’s relative isolation behind the wall is bad for business. It would help if Israelis could go there to spend money, but they can’t.

Advertisement

To get back to Jerusalem, I shuffled through the checkpoint with several hundred Palestinians. We were required to move slowly through a narrow tunnel of steel mesh, as though we were prisoners entering a high- security jail. There was an air of resignation. People didn’t talk much. When they did, the conversation was muted. Mothers tried to keep their children calm. Young men tapped nervously on their cell phones. Some people laughed at an anxious joke. You cannot allow tempers to fray when you are crushed together in a cage.

The odd thing was that Israeli soldiers were nowhere to be seen. No jeeps, no watchtowers or patrols. Once every ten, fifteen, sometimes twenty minutes, a green light would briefly start blinking, a gate would open with a loud clunk, and a few people at a time could proceed to the next gate. I was lucky. It only took an hour and a half this time. After the last gate shut behind me, I finally saw two Israeli soldiers through the tiny window of a small, airless office, young women of around twenty, giggling and chatting as they pressed the button that opened the gates, casually, with all the time in the world. A boring job, no doubt. They barely saw the Palestinians, whose documents they scrutinized before at last allowing them to emerge into the open air.

2.

Every Friday afternoon, without fail, several hundred people, sometimes more, never less, gather on a dusty corner of East Jerusalem, a few minutes’ walk from the famous American Colony Hotel. They are there to protest against the evictions of Palestinian families from their homes. The Palestinians are thrown out, and Jewish settlers move in, dressed in the dark suits and black hats of their ultra-Orthodox faith. This is Sheikh Jarrah, a mostly Arab neighborhood. After the 1948 war, Palestinian refugees were resettled there, on what was then Jordanian territory, and were allowed to stay after the area was reclaimed by Israel in 1967.

This arrangement changed some years ago, when various Jewish organizations, religious and secular, decided to lay claim to homes that had belonged to Jews before 1948. The grounds for this are not always straightforward, sometimes relying on documents dating back to the Ottoman Empire whose provenance is often contested. In some areas, though not necessarily Sheikh Jarrah, Palestinians pretend that they are being evicted after selling their properties to Jews, a serious crime in Palestine. In any case, Palestinians do not have the same right to repossess their lost properties in West Jerusalem. It is all part of a wider Israeli strategy to gradually reclaim the whole of Jerusalem, including many surrounding villages, by moving Palestinians out, often forcefully, and Jews in. As Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu once put it: “Jerusalem is not a settlement, it is the capital of Israel.”

The Israeli protest against these practices was started by Hebrew University students. They are joined every Friday by well-known academic and literary figures, such as David Grossman, Zeev Sternhell, Avishai Margalit, David Shulman, and even a former attorney general, who was born in the area, named Michael Ben-Yair. Some people shout slogans, sing songs, or carry placards saying “Stop the occupation!” or “Stop ethnic cleansing!” But most just turn up, every week, as a show of solidarity.

Apart from the young Arab boys who come to sell freshly squeezed orange juice to the protesters, there are not many Palestinians on the scene. This is less true of demonstrations outside Jerusalem. Here, the worst that can happen to a Jew is to be beaten up and spend a day in a police lockup. If a Palestinian is caught, he might lose his permit to live in Jerusalem, and thereby his home, his job, his livelihood.

The protests are lawful. Even so, at first the demonstrators were badly roughed up by the police who block off the road to the new Israeli settlements. Some people got clubbed, there was tear gas, elderly protesters were kicked to the ground. Broadcast on the television news, these scenes caused considerable dismay, and the police were ordered to show more restraint. This is still Jerusalem, after all. Restraint is not deemed quite so urgent in the occupied territories. And so the weekly protests continue, even as more Arabs are evicted and new settlers move in, if not here, then in other Arab neighborhoods: Silwan, Ras al-Amud, Abu Tor, Jabel Mukaber.

Protesters cannot do very much about this state of affairs. But even symbolic gestures count in a country where most people seem to have become hardened to the humiliation and ill-treatment of a minority living in their midst. The protests show that there is still a sense of decency in a nation coarsened by daily brutalities. In a way, the Sheikh Jarrah Solidarity Movement is the most noble form of patriotism.

Advertisement

I usually went to the weekly protest with an old friend called Amira, like the Palestinian waitress. But my friend is Jewish, and Israeli. The evictions, dumping families into the streets, the behavior of the settlers, the general attitude of Israelis toward the Palestinians, trigger a rage in her that lasts well beyond the weekly protests. It is always there, smoldering, often expressed in a kind of loathing of her own country. She is disgusted by the sight of Israelis having a good time in bars, restaurants, and coffee shops while the Arabs continue to be humiliated. Some might interpret this as neurotic, a form of self-hatred. But I don’t think so.

“You must understand,” her husband, who is British, explained to me one Friday afternoon.

Amira is really very patriotic. She grew up full of Zionist idealism. She was taught to believe that Israel was a great experiment in building a new, more humane society. Disillusion began in her late high school years. Amira, and others, especially of an older generation, are furious because they have seen those ideals collapse. They can’t recognize their own country anymore. It’s as if they’ve been robbed of their dreams.

3.

It was pouring with rain in Sheikh Jarrah, but still the Israeli protesters gathered, and the young Palestinian boys squeezed oranges under an improvised tent whose roof periodically released floods of rainwater. And there, as always, was Ezra Nawi, perhaps the most remarkable figure among the Israeli activists, pressing the flesh with the energetic bonhomie of a born politician.

In fact, Ezra, a stocky man with thick eyebrows and a bronze complexion, is not a politician at all, but a plumber, a gay Jewish plumber, from an Iraqi Jewish family. He became an activist in an Arab-Jewish human rights group in the 1980s after becoming intimately acquainted with the hardships of Arab life in Israel through his Palestinian lover.

Ezra’s activism is more practical than overtly political. He goes wherever Palestinians are in trouble, being chased off their land by the Israeli army, or assaulted by armed Israeli settlers. His main area of operation is south Hebron, where Bedouins try to survive as best they can in the desert or in the slums. When they refuse to move from their land, their animals are poisoned, their wells blocked, and their plots of land destroyed or simply confiscated. Israeli settlements surround the squalid towns where Arab shepherds, deprived of their traditional livelihoods, are often forced to live.

This is a lawless place, where young armed men in black hats make their own rules. And when they need more force against the natives, they can call in the army. These men and women came to this land from all over the world, from the US, Europe, South Africa, Russia, and Israel too.

I set off one Saturday, with Ezra and a number of other activists, including David Shulman, the eminent Iowa-born Israeli scholar of Indian civilization. Not far from a large Israeli settlement, we stood at the edge of a small brown field, watching a Palestinian farmer sow seeds with a flick of the wrist, rather like a fisherman casting with his rod, while another man drove an old tractor up and down. On the other side of the field stood a group of Israeli soldiers, guns slung across their shoulders. We were there, David explained to me, to make sure settlers didn’t come to prevent the Palestinians from planting their seeds. Often the soldiers, at the behest of the settlers, would chase the activists away, or even arrest them. This is not legal. But, as mentioned earlier, the law does not usually stretch to these ancient lands.

This time they kept their distance, and the seeds were sown. Meanwhile, Ezra had already gone ahead to another trouble spot. Settlers had erected fences around a field that had belonged to a Palestinian family for generations, until it was taken away from them a decade ago. The reasons for these confiscations are variable; in this case the army had claimed it was necessary for military exercises, which didn’t prevent Israelis from building their settlements there.

While surveying the majestic rocky landscape, stretching all the way to the Negev desert, David remarked that these wild places tend to attract crazy people. This was once the land where prophets and other holy men roamed. As he spoke, I heard a raucous voice yelling something in German. On the other side of the new fence stood a wiry man in a black cowboy hat and black jeans. He spoke with the fury of a fanatic. His name was Yohanan. He was shouting at a middle-aged Palestinian, telling him to shut up (Maul halten!).

The Palestinian explained in Arabic that this land had belonged to his family for generations. Yohanan, a Jewish convert, born as the son of a Catholic priest, said there was no proof of this. He did not invoke the Bible, however, to bolster his own claim to this bit of what he called Judea and Samaria. He talked like a pre-war German nature worshiper. He spoke fervently about his special relationship with the land, his understanding of the plants that grew there. In Germany, he pointed out, if a plot of land is not taken care of by its owner, it falls to the person who works it instead. He was the tiller of this soil, he said, and so the land was his.

Yohanan is an oddball, a loner, disliked by other Israeli settlers. His house, a kind of improvised caravan, stood in isolation on a nearby hill. He had some dark tales of Israeli violence, of vengeance, and festering feuds. It is tempting to see the violence in places like south Hebron as deriving from ancient tensions, fed by religious or racial hatred, going back perhaps even to biblical times. In fact, however, the Bedouins are not religious fanatics, nor do they lay sacred claims to their property. And not all the Jewish settlers are fired by religious zeal either. What you see there, on these arid frontiers, is not an Old World story but a New World one, of settlers and natives, of cowboys and Indians, of eccentric gunmen and outlaws. It is how the West was won.

4.

During my stay, the Israeli papers seemed obsessed by sex scandals. Two in particular dominated the news: the conviction of Moshe Katsav, the former president of Israel, of rape, sexual harassment, and “committing indecent acts”; and the accusation made against Police Major General Uri Bar-Lev of “using force in an attempt to have an intimate encounter” with a woman, a social worker identified as “O.”

“O,” as well as another figure in the lurid tales of the general’s love life, named “M,” a cosmetician, were not paid party girls, à la Berlusconi. Major General Bar-Lev met “O” at a conference, and she had known “M” for a long time. A third woman, “S,” had allegedly introduced “M” to Bar-Lev, after he had requested a threesome. Ex-President Katsav, too, knew his accusers well. He even told one that he was in love with her. They were women working in his office, one in the Tourism Ministry when Katsav was minister of tourism, the other two in the President’s Residence.

Remarkably, a recent academic survey by Dr. Avigail Moor revealed that six out of ten Israeli men, and four out of ten women, did not consider “forced sex with an acquaintance” to be rape.1 The case of Bar-Lev seems to have had something to do with office politics. He was a contender to become the new police chief. Not everyone wishes him well. And Katsav’s deeds point to office politics of a more brutal kind. The tone in Israeli papers, censorious and lip-smacking at the same time, reminded me of the British tabloids—in the words of a Haaretz columnist, “that well-known combination of pornography and self-righteousness.”2

Public scandals were not the only items in the papers to do with sex, however. There was also the open letter from thirty-odd wives of prominent rabbis, belonging to an organization aimed at “saving the daughters of Israel.” The letter called on Jewish girls not to date Arab boys. “They seek your company,” the letter warned, “try to get you to like them, and give you all the attention in the world.” And then you are trapped. One rabbi, named Shmuel Eliyahu, notorious for telling people in his town of Safed not to rent or sell apartments to Arabs, expressed a similar sentiment. He said that he was happy to be civil to Arabs, but, he added: “I don’t want the Arabs to say hello to our daughters.”

Rabbi Eliyahu, it should be said, is reviled by the liberal Israeli press, and does not enjoy wide support in the country. And yet, to dismiss him as a complete maverick would be a mistake. A survey conducted jointly by Israelis and Palestinians found that 44 percent of Jewish Israelis support the call to stop renting apartments to Arabs in Safed. One can only guess what the figure would be if the question involved sexual relations between Jews and Arabs, but it would probably be considerably higher.

5.

About a mile separates Al-Quds University from the Old City of Jerusalem. Catering to more than ten thousand undergraduates and postgraduates, Al-Quds is the only Arab university in the Jerusalem area. You could walk there in about twenty minutes from the Old City. But you cannot do so anymore, since the wall separating Israelis from Palestinians cuts the university off from the city. The original plan in 2003 was to run the wall right through the campus, destroying two playing fields, a car park, and a garden. Protests from faculty and students, backed by the US government, stopped this from happening. But the place still feels isolated. To get there from Jerusalem, you have to breach the wall and pass through several checkpoints. The twenty-minute walk is now a forty-minute drive, but only if you have the right permits and if the soldiers manning the checkpoints don’t wish to detain you. Israelis are not supposed to go there at all.

Despite being cut off, Al-Quds, whose president is Sari Nusseibeh, one of the great liberal minds in Palestine, feels like a lively institution. Muslim students in headscarves mingle with secular students and Christians. There are Jewish professors too. And most Palestinians who teach there have degrees from European or American universities.

I visited Al-Quds on the last day of my stay in Jerusalem. The reason, apart from my curiosity to visit a Palestinian campus, was that Al-Quds has a partnership with Bard College, where I teach in the US. I was invited to a class on urban studies. The students presented papers on a remarkable plan to build a completely new Palestinian city, named Rawabi, just north of Ramallah. Construction work has already begun, even though the Israeli government has not yet given permission to build an access road, without which Rawabi would be stuck on a rocky mountaintop, with views of Tel Aviv but no road to Ramallah.

One of the students, a young woman in a headscarf, explained what Rawabi would look like, with office towers, American-style suburban homes, and all the comforts so often lacking in Palestinians towns today: electricity, running water, Internet connections, and sources for green energy. It would have cinemas, a hospital, cafés, a conference center, underground garages, and a large park. Rawabi, in short, is the stuff of Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s dreams, the smart new Palestine, financed in this case mostly by the government of Qatar. And Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu is said to be in favor too, for this would spell a kind of “normalization” without Israeli concessions.

This alone would be enough to raise Palestinian suspicions. Would such a project not be an abject form of collaboration? Is it not a way of acquiescing to the status quo? The students of Al-Quds could not make up their minds. They were excited about the plans for a new, modern, urban Palestine but could not shake off a sense of deep ambivalence.

For there are other problems, besides Netanyahu’s alleged enthusiasm. Prime Minister Fayyad is not popular among many Palestinians. Hamas may not be much loved on the West Bank, but the news, revealed on an al-Jazeera website, that Fayyad is cooperating with the Israeli army to suppress fellow Palestinians was not generally well received. Nor was the fact that—also revealed on al-Jazeera—the Palestinian Authority was prepared to concede parts of East Jerusalem to Israeli control. Aware of his vulnerability, Fayyad, almost as soon as the crowds revolted in Egypt, dissolved his cabinet and promised elections in September.

The Al-Quds students did not dwell on these political issues, but they did mention that Israeli firms have been contracted to take part in the construction of Rawabi. Even worse, in some Palestinian eyes, the developer, Bashar Masri, has accepted a donation from the Jewish National Fund of three thousand tree saplings, as a “green contribution.” One blogger denounced these as “damned Zionist trees.”

But it gets even more complicated. If Palestinians have doubts, so do Israeli settlers, who have staged demonstrations against the project and tried to disrupt its construction. Rawabi is a “threat to security,” they claim. Rawabi is a step toward building a Palestinian state. Rawabi, they say, will cause pollution, traffic jams, and much else. What the settlers really can’t stand is that Rawabi will be towering over them. Before Rawabi, Israeli settlements, illegal according to international law, always towered over the Palestinians.

The students of Al-Quds argued back and forth, the women more vociferously than the men. In the end, they remained ambivalent. There was no absolutely right answer, no solution that would suit everyone. That they were clearly aware of this, and continued arguing, left me with a sliver of hope amid the melancholy of a country slowly being torn apart by people whose claims are never anything but absolute.

—March 8, 2011

This Issue

April 7, 2011